[Speech by T. W. Stanton, Given at the 50Th Anniversary Meeting of the Geological Society of Washington, Feb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings Op the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting Op the Geological Society Op America, Held at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, December 21, 28, and 29, 1910

BULLETIN OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA VOL. 22, PP. 1-84, PLS. 1-6 M/SRCH 31, 1911 PROCEEDINGS OP THE TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING OP THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OP AMERICA, HELD AT PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA, DECEMBER 21, 28, AND 29, 1910. Edmund Otis Hovey, Secretary CONTENTS Page Session of Tuesday, December 27............................................................................. 2 Election of Auditing Committee....................................................................... 2 Election of officers................................................................................................ 2 Election of Fellows................................................................................................ 3 Election of Correspondents................................................................................. 3 Memoir of J. C. Ii. Laflamme (with bibliography) ; by John M. Clarke. 4 Memoir of William Harmon Niles; by George H. Barton....................... 8 Memoir of David Pearce Penhallow (with bibliography) ; by Alfred E. Barlow..................................................................................................................... 15 Memoir of William George Tight (with bibliography) ; by J. A. Bownocker.............................................................................................................. 19 Memoir of Robert Parr Whitfield (with bibliography by L. Hussa- kof) ; by John M. Clarke............................................................................... 22 Memoir of Thomas -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

The EERI Oral History Series

CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace Stanley Scott, Interviewer Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Editor: Gail Hynes Shea, Albany, CA ([email protected]) Cover and book design: Laura H. Moger, Moorpark, CA Copyright ©1999 by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part may be reproduced, quoted, or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the executive director of the Earthquake Engi- neering Research Institute or the Director of the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the oral history subject and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute or the University of California. Published by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 499 14th Street, Suite 320 Oakland, CA 94612-1934 Tel: (510) 451-0905 Fax: (510) 451-5411 E-Mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.eeri.org EERI Publication No.: OHS-6 ISBN 0-943198-99-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wallace, R. E. (Robert Earl), 1916- Robert E. Wallace / Stanley Scott, interviewer. p. cm – (Connections: the EERI oral history series ; 7) (EERI publication ; no. -

George P. Merrill Collection, Circa 1800-1930 and Undated

George P. Merrill Collection, circa 1800-1930 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: PHOTOGRAPHS, CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED MATERIAL CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL GEOLOGISTS AND SCIENTISTS, CIRCA 1800-1920................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: PHOTOGRAPHS OF GROUPS OF GEOLOGISTS, SCIENTISTS AND SMITHSONIAN STAFF, CIRCA 1860-1930........................................................... 30 Series 3: PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES (HAYDEN SURVEYS), CIRCA 1871-1877.............................................................................................................. -

Bailey Willis

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BAILEY WILLIS 1857—1949 A Biographical Memoir by E L I O T B L A C KWELDER Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1961 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. BAILEY WILLIS May 3/, i8^j-February 19,1949 BY ELIOT BLACKWELDER HILE it is not easy to classify as versatile a man as Bailey W Willis, the word explorer fits him best. Although he came too late for the early period of geologic exploration of the western states, he was associated with many of those who had taken part in it, and he grew up with its later stage. The son of a noted poet, it is not strange that he displayed much of the temperament of an artist and that his scientific work should have leaned toward the imaginative and speculative side rather than the rigorously factual. Willis was born on a country estate at Idlewild-on-Hudson in New York, on May 31, 1857. His father, Nathaniel Parker Willis, whose Puritan ancestors settled in Boston in 1630, was well known as a journalist, poet and writer of essays and commentaries; but he died when Bailey was only ten years old. His mother, Cornelia Grinnell Willis, of Quaker ancestry, seems to have been his principal mentor in his youth, inspiring his interest in travel, adventure and explora- tion. At the age of thirteen he was taken to England and Germany for four years of schooling. -

Raphael Pumpelly 1837—1923

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XVI SECOND MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF RAPHAEL PUMPELLY 1837—1923 BY BAILEY WILLIS PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE AUTUMN MEETING, 1931 MIOMOKML OF li.W'IIAKL I'l'iU'KLLl' ' HY liAII.EY WILLIS CO N'TK NTS Page Foreword 23 Boyhood 23 Freiberg, 185U to 18(i() 29 Corsica, 1856 to 1857 31 Arizona, 1800 to 18G1 34 Japan and China. 1861 to 1864 36 Lake Superior, 1865 to 1877.. 42 Missouri, 1871 and 1872 47 Loess and Secular Disintegration, 1863 and 1876 47 Official Surveys, 1870 to 1890 49 (Ireen Mountain Studies 52 Explorations in Central Asia, 1903 to 1904 56 Dublin, New Hampshire "® Bibliography SI FOKKWOlil) 1'iunpelly's place is among the great explorers. He inherited the spirit; his environment gave the motive; he achieved the career by virtue of his physical endowment, his high courage, and his mental and moral fitness. His interest in geology was• first aroused by his mother, an unusually gifted woman, and was fixed by early incidental opportunities for ob- servations in'Germany and Corsica, followed by a chance meeting with the German geologist, Noeggeratli, which led to his going to the mining school at Freiberg. He used his profession of mining engineer, but never devoted himself to it. He served his adopted science, geology, but not exclusively; yet his contributions to its principles and knowledge remain unchallenged after thirty to fifty years of later intensive research along the same lines. He cherished for forty years a dream of carrying out investigations in the archeology and ethnology of the Asiatic and European races and at the age of three score and ten realized it with that same thoroughness and devotion to truth which characterized all of his scientific studies. -

Bailey Willis Glass Plate Photonegatives Collection

Bailey Willis Glass Plate Photonegatives Collection Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives Washington, D.C. 20013 [email protected] https://www.freersackler.si.edu/research/archives/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Local Numbers................................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical................................................................................................... -

“For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People”

“For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People” A HISTORY OF CONCESSION DEVELOPMENT IN YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, 1872–1966 By Mary Shivers Culpin National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR-CR-2003-01, 2003 Photos courtesy of Yellowstone National Park unless otherwise noted. Cover photos are Haynes postcards courtesy of the author. Suggested citation: Culpin, Mary Shivers. 2003. “For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People”: A History of the Concession Development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872–1966. National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, YCR-CR-2003-01. Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................................iv Preface .................................................................................................................................... vii 1. The Early Years, 1872–1881 .............................................................................................. 1 2. Suspicion, Chaos, and the End of Civilian Rule, 1883–1885 ............................................ 9 3. Gibson and the Yellowstone Park Association, 1886–1891 .............................................33 4. Camping Gains a Foothold, 1892–1899........................................................................... 39 5. Competition Among Concessioners, 1900–1914 ............................................................. 47 6. Changes Sweep the Park, 1915–1918 -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (?) Dwight Eugene Mavo 1968

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-9041 MAYO, Dwight Eugene, 1919- THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE IDEA OF THE GEOSYNCLINE. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1968 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (?) Dwight Eugene Mavo 1968 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 'i hii UIUV&Hüil Y OF O&LAÜOM GRADUAS ü COLLEGE THS DEVlïLOFr-ÎEKS OF TÜE IDEA OF SHE GSOSÏNCLIKE A DISDER'i'ATIOH SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUAT E FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY DWIGHT’ EUGENE MAYO Norman, Oklahoma 1968 THE DEVELOfMEbM OF THE IDEA OF I HE GEOSÏHCLINE APPROVED BÏ DIS5ERTAII0K COMMITTEE ACKNOWL&DG EMEK3S The preparation of this dissertation, which is sub mitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy at the University of Okla homa, has been materially assisted by Professors Duane H, D. Roller, David b, Kitts, and Thomas M. Smith, without whose help, advice, and direction the project would have been well-nigh impossible. Acknowledgment is also made for the frequent and generous assistance of Mrs. George Goodman, librarian of the DeGolyer Collection in the history of Science and Technology where the bulk of the preparation was done. ___ Generous help and advice in searching manuscript materials was provided by Miss Juliet Wolohan, director of the Historical Manuscripts Division of the New fork State Library, Albany, New fork; Mr. M. D. Smith, manuscripts librarian at the American Philosophical Society Library, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Dr. Kathan Seingold, editor of the Joseph Henry Papers, bmithsonian Institution, Wash ington, D. -

Geological History of the Yellowstone National Park

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 1912 WASHINGTON ; GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1912 This publication may be purchased from the Superintendent of Docu ments, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., for 10 cents. 8 GEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK. By ARNOLD HAGUE, United States Geological Survey. The purpose of this paper is not so much to elucidate any special problem connected with the many interesting geological questions to be found in the Yellowstone Park, as to offer such a general view of the region as will enable the tourist to understand clearly something of its physical geography and geology. The Yellowstone Park is situated in the extreme northwestern portion of Wyoming. At the time of the enactment of the law establishing this national reservation the region had been little explored, and its relation to the physical features of the adjacent country was little understood. Since that time surveys have shown that only a narrow strip about 2 miles in width is situated in Montana and that a still narrower strip extends westward into Idaho. The area of the park as at present defined is somewhat more than 3,300 square miles. The Central Plateau, with the adjacent mountains, presents a sharply defined region, in strong contrast with the rest of the northern Rocky Mountains. It stands out boldly, is unique in topographical structure, and complete as a geological problem. The central portion of the Yellowstone Park is essentially a broad, elevated, volcanic plateau, between 7,000 and 8,500 feet above sea level, and with an average elevation of about 8,000 feet. -

United States Geological Survey Secretary of The

THIRTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TO THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR 1891-'92 BY J. W. POWELL DIRECTOR IN THREE PARTS PART I-REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1892 THIRTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DII~ HCCTOH OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY. Part I.—REPORT OF DIRECTOR. III CONTENTS. REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR. Page. Letter of i ransmittal 1 Plan of operations for the fiscal year 1891—'92 3 Topography 4 Supervision, disbursements, etc . 4 Northeastern section 5 Southeastern section 6 Central section California gold-belt section 7 Southern California section 7 Colorado, South Dakota, and Wyoming section 7 Idaho section 7 Montana section 8 Texas section 8 Washington section 8 Special work 8 Miscellaneous office work 8 Geology 9 Executive office, etc 10 Division of geologic correlation 10 Atlantic coast division 11 Archean division 11 New Jersey division 12 Potomac division . 12 Appalachian division 12 Florida division 13 Lake Superior division . ................ ...... ............. 13 Division of glacial geology 13 Division of zinc 13 Montana division 14 Yellowstone Park division 14 Colorado division_ 11 Cascade division and petrographic laboratory 15 Calfornia division 15 Miscellaneous 15 Paleontology _ 16 Division of Paleozoic invertebrates. 16 Division of lower Mesozoic paleontology 17 Division of upper Mesozoic paleontology 18 Division of Cenozoic paleontology 18 Division of paleobotany 18 Division of fossil insects 19 Division of vertebrate paleontology -

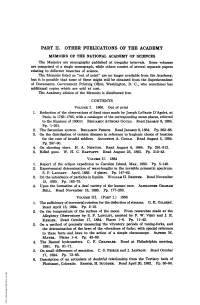

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2.