Daf Ditty Eruvin 39-Yoma Aruchta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline of the Generations (Haazinu)

21 Sep 2020 – 3 Tishri 5781 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Haazinu The Decline of the Generations Introduction In this week’s Torah portion, Haazinu, Moses tells the Israelites to remember their people’s past: זְכֹר֙יְמֹ֣ות םעֹולָָ֔ ב ִּ֖ ינּו נ֣ שְ ֹותּדֹור־וָד֑ ֹור שְאַַ֤ ל אָב ֙יך֙ וְ יַגֵָ֔דְ ךזְקֵנ ִּ֖יך וְ יֹֹ֥אמְ רּו לְָָֽך Remember the days of old. Consider the years of generation after generation. Ask your father and he will inform you; your elders, and they will tell you. [Deut. 32:7] He then warns them that prosperity (growing “fat, thick and rotund”) and contact with idolaters will cause them to fall away from their faith, so they should keep alive their connection with their past. Yeridat HaDorot Strong rabbinic doctrine: Yeridat HaDorot – the decline of the generations. Successive generations are further and further away from the revelation at Sinai, and so their spirituality and ability to understand the Torah weakens steadily. Also, errors of transmission may have been introduced, especially considering a lot of the Law was oral: מש הק בֵלּתֹורָ ה מ סינַי, ּומְ סָרָ ּהל יהֹושֻׁעַ , ו יהֹושֻׁעַ ל זְקֵנים, ּוזְקֵנים ל נְב יאים, ּונְב יא ים מְ סָ רּוהָ ילְאַנְשֵ נכְ ס ת הַגְדֹולָה Moses received the Torah from Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly. [Avot 1:1] The Mishnah mourns the Sages of ages past and the fact that they will never be replaced: When Rabbi Meir died, the composers of parables ceased. -

Guide to Practical Halacha and Home Ritual for Conservative Jews

DRAFT Guide to Practical Halacha and Home Ritual For Conservative Jews By Yehuda Wiesen Last Revised August 11, 2004 I am looking for a publisher for this Guide. Contact me with suggestions. (Contact info is on page 2.) Copyright © 1998,1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 Joel P. Wiesen Newton, Massachusetts 02459 Limited and revocable permission is granted to reproduce this book as follows: (a) the copyright notice must remain in place on each page (if less than a page is reproduced, the source must be cited as it appears at the bottom of each page), (b) the reproduction may be distributed only for non-profit purposes, and (c) no charge may be made for copying, mailing or distribution of the copies. All requests for other reproduction rights should be addressed to the author. DRAFT Guide to Practical Halacha and Home Ritual For Conservative Jews Preface Many Conservative Jews have a strong desire to learn some practical and ritual halacha (Jewish law) but have no ready source of succinct information. Often the only readily available books or web sites present an Orthodox viewpoint. This Guide is meant to provide an introduction to selected practical halachic topics from the viewpoint of Conservative Judaism. In addition, it gives some instruction on how to conduct various home rituals, and gives basic guidance for some major life events and other situations when a Rabbi may not be immediately available. Halacha is a guide to living a religious, ethical and moral life of the type expected and required of a Jew. Halacha covers all aspects of life, including, for example, food, business law and ethics, marriage, raising children, birth, death, mourning, holidays, and prayer. -

Yoma Book.Indb

Perek V Daf 56 Amud a BACKGROUND ten log that I will later separate shall be the fi rst tithe;N and another ֲﬠ ָׂשָרה ַמ ֲﬠ ֵׂשר ִר ׁאשוֹן, ִּת ׁ ְש ָﬠה ַמ ֲﬠ ֵׂשר Terumot and tithes : ְּת ּרומוֹת ּו ַמ ַﬠ ְׂשרוֹת – tenth from the rest, which equals nine log of the remaining ninety, Terumot and tithes are separated in the following manner. For example, if one ׁ ֵש ִני, ּו ֵמ ֵיחל ְו ׁש ֶוֹתה ִמ ָיּד, ִ ּד ְבֵרי ַר ִּבי -shall be second tithe. And he redeems the second tithe with money has one hundred units of food or beverage, he first re ֵמ ִאיר. that he will later take to Jerusalem, and he may then immediately moves the teruma gedola, which is given to the priests. The N drink the wine. Aft er Shabbat, when he removes portions from the average amount of this gift is one-fiftieth of the produce, mixture and places them in vessels, they are retroactively designated which in this example is two units. Next, the first tithe is B as terumot and tithes. Th is is the statement of Rabbi Meir. removed and given to a Levite. This gift is ten percent of the remaining produce, or slightly less than ten units in this case. In most years, another tenth is taken from the rest as second tithe, which is taken to Jerusalem and consumed there. Here the second tithe amounts to slightly more than nine units. In years three and six of the Sabbatical cycle, this tithe is given to the poor instead. -

Pesach for the Year 5780 Times Listed Are for Passaic, NJ Based in Part Upon the Guide Prepared by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches (Yeshivah Shul – Young Yeshivah, Melbourne)

בס״ד Laws and Customs: Pesach For the year 5780 Times listed are for Passaic, NJ Based in part upon the guide prepared by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches (Yeshivah Shul – Young Yeshivah, Melbourne) THIRTY DAYS BEFORE PESACH not to impact one’s Sefiras Haomer. CLEANING AWAY THE [Alert: Polar flight routes can be From Purim onward, one should learn CHAMETZ equally, if not more, problematic. and become fluent in the Halachos of Guidance should be sought from a It is improper to complain about the Pesach. Since an inspiring Pesach is Rav familiar with these matters.] work and effort required in preparing the product of diligent preparation, for Pesach. one should learn Maamarim which MONTH OF NISSAN focus on its inner dimension. Matzah One should remember to clean or Tachnun is not recited the entire is not eaten. However, until the end- discard any Chometz found in the month. Similarly, Av Harachamim and time for eating Chometz on Erev “less obvious” locations such as Tzidkasecha are omitted each Pesach, one may eat Matzah-like vacuum cleaners, brooms, mops, floor Shabbos. crackers which are really Chometz or ducts, kitchen walls, car interiors egg-Matzah. One may also eat Matzah The Nossi is recited each of the first (including rented cars), car-seats, balls or foods containing Matzah twelve days of Nissan, followed by the baby carriages, highchairs (the tray meal. One may also be lenient for Yehi Ratzon printed in the Siddur. It is should also be lined), briefcases, children below the age of Chinuch. recited even by a Kohen and Levi. -

Eruvin 079.Pub

ט' חשון תשפ“אTues, Oct 27 2020 OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT ביטול Pebbles (cont.) Defining the duration of (1 הח איסור שבת דאפילו ארקי מי מבטל -Three accepted resolutions are presented to resolve the con tradiction between our Mishnah and a Mishnah in Ohalos re- garding pebbles. T he Gemara (Sukkah 4a) discusses a sukkah which is unac- 2) Placing a board over the ditch ceptable because its roof of schach is higher than twenty amos Rava distinguishes with regards to the ruling in the Mish- above the floor. Straw or dirt is then placed in a pile to be left nah between placing the board across the width of the ditch there, thus causing the distance between the heightened floor and placing it across the length of the ditch. and the schach to be within twenty amos. The Gemara rules 3) Balconies that this is acceptable. The question the rishonim discuss is must be forever, or if it is enough for the pile ביטול Rava presents different ways the balconies could be ar- whether the ranged and the halachos for each arrangement. of dirt or straw to be intended to be left in its spot for the dura- 4) MISHNAH: The Mishnah discusses the issue of a haystack tion of the seven days of Sukkos. Those who maintain that it is to be for seven days bring a proof from ביטול that separates two chatzeros. adequate for the 5) Feeding animals from the haystack our Gemara, where a wallet is considered to be “permanently R’ Huna rules that one may not take straw from the hay- placed”, even though it will only remain in its place for the du- ration of Shabbos. -

What Sugyot Should an Educated Jew Know?

What Sugyot Should An Educated Jew Know? Jon A. Levisohn Updated: May, 2009 What are the Talmudic sugyot (topics or discussions) that every educated Jew ought to know, the most famous or significant Talmudic discussions? Beginning in the fall of 2008, about 25 responses to this question were collected: some formal Top Ten lists, many informal nominations, and some recommendations for further reading. Setting aside the recommendations for further reading, 82 sugyot were mentioned, with (only!) 16 of them duplicates, leaving 66 distinct nominated sugyot. This is hardly a Top Ten list; while twelve sugyot received multiple nominations, the methodology does not generate any confidence in a differentiation between these and the others. And the criteria clearly range widely, with the result that the nominees include both aggadic and halakhic sugyot, and sugyot chosen for their theological and ideological significance, their contemporary practical significance, or their centrality in discussions among commentators. Or in some cases, perhaps simply their idiosyncrasy. Presumably because of the way the question was framed, they are all sugyot in the Babylonian Talmud (although one response did point to texts in Sefer ha-Aggadah). Furthermore, the framing of the question tended to generate sugyot in the sense of specific texts, rather than sugyot in the sense of centrally important rabbinic concepts; in cases of the latter, the cited text is sometimes the locus classicus but sometimes just one of many. Consider, for example, mitzvot aseh she-ha-zeman gerama (time-bound positive mitzvoth, no. 38). The resulting list is quite obviously the product of a committee, via a process of addition without subtraction or prioritization. -

Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life

Wed 6 May 2020 / 12 Iyar 5780 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Adult Education Pikuach Nefesh -- Saving a Life Introduction Judaism enjoins us to save lives. The Torah says: You shall not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor. [Leviticus 19:16] and ּושְׁמַרְׁתֶֶּ֤םאֶת־חֻקֹּתַי֙ וְׁאֶ ת־מִשְׁ פָּטַַ֔ יאֲשֶֶׁ֨ ר יַעֲשֶ ֶׂ֥ ה אֹּתָּ ָ֛ם הָּאָּדָּ ָ֖ם וָּחַ ַ֣י בָּהֶ ֶ֑םאֲנִ ָ֖ייְׁהוָָּֽה You shall therefore keep my statutes and my ordinances, which, if a man performs, he shall live by them. I am the Lord. [Leviticus 18:5] These words were echoed much later by the prophet Ezekiel. [Ezekiel 20:11] The Talmud derives from the verse “you shall live by them” that Jews must live by the Torah and not die because of it. This is the doctrine of Pikuach regard for human life. Even if you must break -- (פִ קּוחַ נֶפש) Nefesh commandments to save a life (yours or another's), do so. Alternate Talmudic logic: The objective is to maximize observance of commandments. Allowing someone to live increases the number of commandments observed. Example: Violating Shabbat to save someone allows him to observe other Shabbatot in the future. [Yoma 85b, Shabbat 151b] Mishna: If uncertain whether life is truly in danger, err on the side of assuming it is. [Yoma 8:6] If turns out there was no threat to human life, no sin and no reason to feel guilty. How far can you go? The Talmud says that healing is prohibited on Shabbat because you need to crush herbs to make medicine, and crushing is prohibited on Shabbat. -

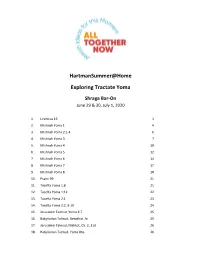

Hartmansummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma

HartmanSummer@Home Exploring Tractate Yoma Shraga Bar-On June 29 & 30, July 1, 2020 1. Leviticus 16 1 2. Mishnah Yoma 1 4 3. Mishnah Yoma 2:1-4 6 4. Mishnah Yoma 3 7 5. Mishnah Yoma 4 10 6. Mishnah Yoma 5 12 7. Mishnah Yoma 6 14 8. Mishnah Yoma 7 17 9. Mishnah Yoma 8 18 10. Psalm 99 21 11. Tosefta Yoma 1:8 21 12. Tosefta Yoma 1:12 22 13. Tosefta Yoma 2:1 23 14. Tosefta Yoma 2:2, 9-10 24 15. Jerusalem Talmud, Yoma 3:7 25 16. Babylonian Talmud, Berakhot 7a 25 17. Jerusalem Talmud, Makkot, Ch. 2, 31d 26 18. Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 86a 26 The Shalom Hartman Institute is a leading center of Jewish thought and education, serving Israel and North America. Our mission is to strengthen Jewish peoplehood, identity, and pluralism; to enhance the Jewish and democratic character of Israel; and to ensure that Judaism is a compelling force for good in the 21st century. Share what you’re learning this summer! #hartmansummer @SHI_america shalomhartmaninstitute hartmaninstitute 475 Riverside Dr., Suite 1450 New York, NY 10115 212-268-0300 [email protected] | shalomhartman.org 1. Leviticus 16 )א( ַוְיַדֵּבר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַאֲחֵּרי מֹות ְשֵּני ְבֵּני ַאֲהֹרן ְבָקְרָבָתם ִלְפֵּני ה' ַוָיֻמתּו: )ב( ַויֹאֶמר ה' ֶאל ֹמֶשה ַדֵּבר ֶאל ַאֲהֹרן ָאִחיָך ְוַאל ָיבֹא ְבָכל ֵּעת ֶאל ַהֹקֶדש ִמֵּבית ַלָפֹרֶכת ֶאל ְפֵּני ַהַכֹפֶרת ֲאֶשר ַעלָ הָאֹרןְ ולֹאָ ימּות ִכי ֶבָעָנן ֵּאָרֶאה ַעלַהַכֹפֶרת: )ג( ְבזֹאתָיבֹא ַאֲהֹרן ֶאלַהֹקֶדש ְבַפר ֶבן ָבָקר ְלַחָטאת ְוַאִיל ְלֹעָלה: )ד( ְכֹתֶנת ַבד ֹקֶדש ִיְלָבש ּוִמְכְנֵּסי ַבד ִיְהיּו ַעל ְבָשרֹו ּוְבַאְבֵּנט ַבד ַיְחֹגר ּוְבִמְצֶנֶפת -

Several Comments on a Genizah Fragment of Bavli, Eruvin 57B–59A

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 4 Original Research Several comments on a Genizah fragment of Bavli, Eruvin 57B–59A Author: This article refers to a Cairo Genizah fragment related to Bavli, Eruvin tractate 57b–59a, 1 Uri Zur identified as Cambridge, UL T-S F1 (1) 85. FGP No. C 96541. The article begins with a description Affiliation: of the Genizah fragment and presents a reproduction of the fragment itself at the end of the 1Israel Heritage Department, article. Reference is made to the content and several comments are made in an effort to Ariel University, Ariel, Israel characterise the fragment. Corresponding author: Keywords: Genizah; Eruvin; Sugya; Aramaic words; Geographical sites. Uri Zur, [email protected] Dates: Description of the Genizah Fragment Received: 11 Jan. 2019 The Genizah fragment is identified as Cambridge, UL T-S F1 (1) 85, and here I shall discuss one Accepted: 21 May 2019 Published: 12 Nov. 2019 folio (No. C 96541 at the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society) selected at random. How to cite this article: The fragment includes approximately 36 lines. The measurements of the folio are 26.5 cm × 32.3 Zur, U., 2019, ‘Several cm. The measurements of the written area are 20.5 cm × 24.5 cm. The page is torn at the edges comments on a Genizah and a considerable part of it is faded and illegible. The legible part of the fragment, which fragment of Bavli, Eruvin 57B–59A’, HTS Teologiese parallels that of the printed version (Vilna), begins with the words ‘…ve-ha at hu de-amrat’ .(59a) (אין, למקום) ’57b) and ends with the words ‘ein, le-makom) (והא את הוא דאמרת) Studies/Theological Studies 75(3), a5381. -

Diagrams in Rashi's Commentary: a Case Study of Eruvin

177 Diagrams in Rashi’s Commentary: A Case Study of Eruvin 56b By: ELI GENAUER Book illustrations serve multiple purposes. Some are ornamental and, in the case of the Hebrew book, such ornamentation fell under the impera- tive of zeh keli ve-anvehu (Ex. 15:2) to beautify ritual objects.1 Other illus- trations serve a more utilitarian purpose, elucidation and explanation of the text. The first printed Hebrew book to utilize illustrations to elucidate the text (and not for ornamental use) was likely Moses of Coucey’s Sefer Mitzvot Gedolot printed in Rome prior to 1480.2 Of course, explanatory illustrations are not an invention of printing; many medieval commenta- tors make use of this convention. While these illustrations can prove in- valuable in elucidating an otherwise opaque text, in some instances they create more confusion than they assist. In part, however, the failure of these illustrations to explain the text, can, in some instances, be traced to the vagaries of printing rather than to a careless commentator. I would like to thank Dr. Peggy Pearlstein, Dr. Ann Brener and Sharon Horo- witz of the Library of Congress, and Dr. Ezra Chwat of the Israel National Li- brary, for their assistance in helping me obtain much of the source material for this article. I would also like to thank Dan Rabinowitz for his invaluable assis- tance in creating this piece. 1 See, e.g., Abraham M. Habermann, “The Jewish Art of the Printed Book,” in Jewish Art An Illustrated History, rev. ed. Bezalel Narkiss, New York Graphic So- ciety Ltd., Greenwich, Conn.:1971, pp. -

Beruriah and Rachel: Two Women in the Talmud

1 BERURIAH AND RACHEL: TWO WOMEN IN THE TALMUD BERURIAH It is not very often that we find the name of a woman mentioned in the Talmud. Beruriah was one such exception, a great Jewish woman whose wisdom, piety, and learning inspire us to this day. Beruriah lived about one hundred years after the destruction of the Second Temple, which occurred in the year 70 CE. She was the daughter of the great Rabbi Chananiah ben Teradion, who was one of the "Ten Martyrs" whom the Romans killed for spreading the teachings of the Torah among the Jewish people. Beruriah was not only the daughter of a great man but was also the wife of an equally great sage, the saintly Rabbi Meir, one of the most important teachers of the Mishnah. The Talmud tells us many stories about Beruriah. She studied three hundred matters pertaining to Halachah (Jewish law) every day, which would be quite an amazing feat for any scholar. Thus, the Sages frequently asked her views regarding matters of law, especially those laws which applied to women. For instance, the Sages had different opinions about the law of purity and asked Beruriah for her opinion. Rabbi Judah sided with her and recognized her authority. There was another case where there was a dispute between Beruriah and her brother. One of the greatest authorities was asked to judge the case and he said: "Rabbi Chananiah's daughter Beruriah is a greater scholar than his son." Beruriah was very well versed in the Holy Scriptures and could quote from them with ease. -

Summer Halachos Part 3

Volume 12 Issue 11 TOPIC Summer Halachos Part 3 SPONSORED BY: KOF-K KOSHER SUPERVISION Compiled by Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits Reviewed by Rabbi Benzion Schiffenbauer Shlita Edited by: Rabbi Chanoch Levi HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is a Website Management and Emails: monthly publication compiled by Heshy Blaustein Rabbi Moishe Dovid Lebovits, a former chaver kollel of Yeshiva SPONSORED Torah Vodaath and a musmach of Harav Yisroel Belsky zt”l. Rabbi לזכר נשמת מורי ורבי Lebovits currently works as the הרה"ג רב חיים ישראל Rabbinical Administrator for ב"ר דוב זצ"ל בעלסקי the KOF-K Kosher Supervision. Dedicated in memory of Each issue reviews a different area of contemporary halacha ר' שלמה בן פנחס ע"ה with an emphasis on practical applications of the principles SPONSORED discussed. Significant time is spent ensuring the inclusion of לז"נ מרת רחל בת אליעזר ע"ה all relevant shittos on each topic, SPONSORED as well as the psak of Harav Yisroel Belsky, zt”l on current לעילוי נשמת .issues מרת בריינדל חנה ע"ה בת ר' חיים אריה יבלח"ט גערשטנער WHERE TO SEE HALACHICALLY SPEAKING Halachically Speaking is distributed to many shuls. It can be seen in Flatbush, Lakewood, Five Towns, Far Design by: Rockaway, and Queens, The Flatbush Jewish Journal, baltimorejewishlife.com, The SRULY PERL 845.694.7186 Jewish Home, chazaq.org, and frumtoronto.com. It is sent via email to subscribers across the world. SUBSCRIBE To sponsor an issue please call FOR FREE 718-744-4360 and view archives @ © Copyright 2016 www.thehalacha.com by Halachically Speaking Summer ח.( )ברכות Halachos Part 3 בלבד..