Reed and Bourne Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Account of the Origin and Progress of British Influence in Malaya by Sir Frank^,Swettenham,K.C.M.G

pf^: X 1 jT^^Hi^^ ^^^^U^^^ m^^^l^0l^ j4 '**^4sCidfi^^^fc^^l / / UCSB LIBRAIX BRITISH MALAYA BRITISH MALAYA AN ACCOUNT OF THE ORIGIN AND PROGRESS OF BRITISH INFLUENCE IN MALAYA BY SIR FRANK^,SWETTENHAM,K.C.M.G. LATE GOVERNOR &c. OF THE STRAITS COLONY & HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR THE FEDERATED MALAY STATES WITH A SPECIALLY COMPILED MAP NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS RE- PRODUCED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS 6f A FRONTISPIECE IN PHOTOGRAVURE 15>W( LONDON i JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MDCCCCVH Plymouth: william brendon and son, ltd., printers PREFACE is an article of popular belief that Englishmen are born sailors probably it would be more true to IT ; say that they are born administrators. The English- man makes a good sailor because we happen to have hit upon the right training to secure that end ; but, though the Empire is large and the duties of administra- tion important, we have no school where they are taught. Still it would be difficult to devise any responsibility, how- ever onerous and unattractive, which a midshipman would not at once undertake, though it had no concern with sea or ship. Moreover, he would make a very good attempt to solve the problem, because his training fits him to deal intelligently with the unexpected. One may, however, question whether any one but a midshipman would have willingly embarked upon a voyage to discover the means of introducing order into the Malay States, when that task was thrust upon the British Government in 1874. The object of this book is to explain the circumstances under which the experiment was made, the conditions which prevailed, the features of the country and the character of the people ; then to describe the gradual evolution of a system of administration which has no exact parallel, and to tell what this new departure has done for Malaya, what effect it has had on the neighbour- ing British possessions. -

Naracoorte Caves National Park

Department for Environment and Heritage Naracoorte Caves National Park Australian Fossil Mammal Site World Heritage Area www.environment.sa.gov.au Naracoorte Caves Vegetation Wonambi Fossil Centre National Par The vegetation is predominantly Brown Stringybark Step through the doors of the Wonambi Fossil Australian Fossil Mammal Site on the limestone ridge, with River Red Gum lining the Centre into an ancient world where megafauna World Heritage Area banks of the Mosquito Creek. The understorey on the once roamed. The display in the Wonambi Fossil ridge is bracken fern over a diverse array of orchids Centre ‘brings to life’ the megafauna fossils found in the Naracoorte Caves. The self-guided walk Naracoorte Caves National Park covers that flower during spring. through the simulated forest and swampland is approximately 600 hectares of limestone wheelchair accessible and suitable for all ages. ranges and is situated in the Some of the park was cleared for pine forests in the south-east of South Australia, mid 1800s, with other exotic species planted around The Flinders University Gallery has information 10 km south of Naracoorte. the caves. Many of the pines have now been cleared and areas revegetated with endemic species. The panels depicting the various sciences studied at Naracoorte, and touch screen computers to answer The area was first gardens now consist of native plants although a few questions you may have relating to the Wonambi dedicated a forestry of the historic trees remain. Fossil Centre and the fossils of Naracoorte Caves. reserve in 1882, with Fauna the first caretaker Southern employed to look Bentwing Bat The National Parks Code after the caves in The most common marsupial seen at Naracoorte is the Western Grey Kangaroo. -

THE UNIVERSITY Heritage Trail

THE UNIVERSITY Heritage Trail Established by The University of Auckland Business School www.business.auckland.ac.nz ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORIC ATTRACTIONS The University of Auckland Business School is proud to establish the University Heritage Trail through the Business History Project as our gift to the City of Auckland in 2005, our Centenary year. In line with our mission to be recognised as one of Asia-Pacific’s foremost research-led business schools, known for excellence and innovation in research, we support the aims of the Business History Project to identify, capture and celebrate the stories of key contributors to New Zealand and Auckland’s economy. The Business History Project aims to discover the history of Auckland’s entrepreneurs, traders, merchants, visionaries and industrialists who have left a legacy of inspiring stories and memorable landmarks. Their ideas, enthusiasm and determination have helped to build our nation’s economy and encourage talent for enterprise. The University of Auckland Business School believes it is time to comprehensively present the remarkable journey that has seen our city grow from a collection of small villages to the country’s commercial powerhouse. Capturing the history of the people and buildings of our own University through The University Heritage Trail will enable us to begin to understand the rich history at the doorstep of The University of Auckland. Special thanks to our Business History project sponsors: The David Levene Charitable Trust DB Breweries Limited Barfoot and Thompson And -

Annual Report2003&Stats

���������������������������������� ������������� ����������� 1 Libraries Board of South Australia Annual Report 2002-2003 Annual report production Coordination and editing by Carolyn Spooner, Project Officer. Assistance by Danielle Disibio, Events and Publications Officer. Cover photographs reproduced with kind permission of John Gollings Photography. Desktop publishing by Anneli Hillier, Reformatting Officer. Scans by Mario Sanchez, Contract Digitiser. Cover and report design by John Nowland Design. Published in Adelaide by the Libraries Board of South Australia, 2003. Printed by CM Digital. ISSN 0081-2633. If you require further information on the For information on the programs or services programs or services of the State Library please of PLAIN Central Services please write to the write to the Director, State Library of South Associate Director, PLAIN Central Services, Australia, GPO Box 419, Adelaide SA 5001, or 8 Milner Street, Hindmarsh SA 5007, or check call in person to the State Library on North the website at Terrace, Adelaide, or check the website at www.plain.sa.gov.au www.slsa.sa.gov.au Telephone (08) 8207 7200 Telephone (08) 8348 2311 Freecall 1800 182 013 Facsimile (08) 8340 2524 Facsimile (08) 8207 7207 Email [email protected] Email [email protected] 2 Libraries Board of South Australia 3 Libraries Board of South Australia Annual Report 2002-2003 Annual Report 2002-2003 CONTENTS The Libraries Board of South Australia 4 Chairman’s message 5 Organisation structure and Freedom of Information 6 State Library of South -

Fire Management Plan Reserves of the South East

Fire Management Plan Reserves of the South East Department for Environment and Heritage PREPARE. ACT. SURVIVE. www.environment.sa.gov.auwww.environment.sa.gov.au Included Department for Environment and Heritage Reserves Aberdour CP Custon CP Lake Frome CP Padthaway CP Bangham CP Desert Camp CP Lake Hawdon South CP Penambol CP Baudin Rocks CP Desert Camp CR Lake Robe GR Penguin Island CP Beachport CP Dingley Dell CP Lake St Clair CP Penola CP Belt Hill CP Douglas Point CP Little Dip CP Piccaninnie Ponds CP Bernouilli CR Ewens Ponds CP Lower Glenelg River CP Pine Hill Soak CP Big Heath CP Fairview CP Martin Washpool CP Poocher Swamp GR Big Heath CR Furner CP Mary Seymour CP Reedy Creek CP Bool Lagoon GR Geegeela CP Messent CP Salt Lagoon Islands CP Bucks Lake GR Glen Roy CP Mount Boothby CP Talapar CP Bunbury CR Gower CP Mount Monster CP Tantanoola Caves CP Butcher Gap CP Grass Tree CP Mount Scott CP Telford Scrub CP Calectasia CP Guichen Bay CP Mud Islands GR Tilley Swamp CP Canunda NP Gum Lagoon CP Mullinger Swamp CP Tolderol GR Carpenter Rocks CP Hacks Lagoon CP Naracoorte Caves CR Vivigani Ardune CP Coorong NP Hanson Scrub CP Naracoorte Caves NP Woakwine CR Currency Creek GR Jip Jip CP Nene Valley CP Wolseley Common CP CP = Conservation Park NP = National Park GR = Game Reserve CR = Conservation Reserve For further information please contact: Department for Environment and Heritage Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department for Environment and Heritage office. -

Thursday, 22 June 2017

No. 39 2203 SUPPLEMENTARY GAZETTE THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 22 JUNE 2017 CONTENTS Appointments, Resignations, Etc. ............................................ 2204 Boxing and Martial Arts Act 2000—Notice ............................ 2204 Communities and Social Inclusion Disability Services, Department for—Notices ..................................................... 2205 Consumer and Business Services—Notice .............................. 2205 Controlled Substances Act 1984—Notice ............................... 2208 Domiciliary Care Services—Notice ........................................ 2205 Emergency Services Funding Act 1998—Notice .................... 2206 Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Department of—Notice ....................................................... 2209 Harbors and Navigation Act 1993—Notices ........................... 2206 Health Care Act 2008—Notices .............................................. 2207 Passenger Transport Regulations 2009—Notices .................... 2213 Police Service—Fees and Charges .......................................... 2216 Proclamations .......................................................................... 2223 Public Sector Act 2009—Notice ............................................. 2217 All public Acts appearing in this gazette are to be considered official, and obeyed as such Printed and published weekly by authority of SINEAD O’BRIEN, Government Printer, South Australia $7.21 per issue (plus postage), $361.90 -

SIR WILLIAM JERVOIS Papers, 1877-78 Reel M1185

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SIR WILLIAM JERVOIS Papers, 1877-78 Reel M1185 Mr John Jervois Lloyd’s Lime Street London EC3M 7HL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1981 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Sir William Francis Drummond Jervois (1821-1897) was born at Cowes on the Isle of Wight and educated at Dr Burney’s Academy near Gosport and the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in 1839. He was posted to the Cape of Good Hope in 1841, where he began the first survey of British Kaffirland. He subsequently held a number of posts, including commanding royal engineer for the London district (1855-56), assistant inspector-general of fortifications at the War Office (1856-62) and secretary to the defence committee (1859-75). He was made a colonel in 1867 and knighted in 1874. In 1875 Jervois was sent to Singapore as governor of the Straits Settlements. He antagonised the Colonial Office by pursuing an interventionist policy in the Malayan mainland, crushing a revolt in Perak with troops brought from India and Hong Kong. He was ordered to back down and the annexation of Perak was forbidden. He compiled a report on the defences of Singapore. In 1877, accompanied by Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Scratchley, Jervois carried out a survey of the defences of Australia and New Zealand. In the same year he was promoted major-general and appointed governor of South Australia. He immediately faced a political crisis, following the resignation of the Colton Ministry. There was pressure on Jervois to dissolve Parliament, but he appointed James Boucaut as premier and there were no further troubles. -

Naracoorte Caves

Naracoorte Caves Government of South Australia www.naracoortecaves.sa.gov.au A trip to the Limestone Coast wouldn’t be complete without a visit to the Naracoorte Caves. Recognised as one of the world’s most important fossil sites, the caves offer experiences for visitors of all ages. DAILY TOURS FOSSILS (except Christmas Day) Providing a rare insight into Guided tours are suitable for Australia’s past, Victoria people of all ages. The 30 Fossil Cave (tours at minute tour of Alexandra Cave 10.15am/2.15pm) showcases (tours at 9.30am/1.30pm) is world renowned fossil deposits. ideal for young families, while The Wonambi Fossil Centre rare bats and world renowned recreates the ancient world of fossils can be viewed on hour- Australia’s mega-fauna with long tours. The Wonambi Fossil life-size robotics in a simulated Centre, Wet Cave and the World forest and swamp land. Heritage Walk are self-guided and can be enjoyed at any time during the opening hours. Do you know that we have Adventure Caving tours are also on-site camping available? available (please pre-book). And while you’re here, BATS don’t forget to treat yourself at our award The Bat Observation Centre winning Cave Café. (tours at 11.30am/3.30pm) is the only place in the world where visitors can observe a colony of Adelaide Southern Bent-winged bats in their natural SA habitat. The Bat Cave itself is only accessible to scientists, but using specially designed infra- Victoria red cameras, guides are Melbourne able to provide visitors with a ‘bat’s-eye view’! This tour concludes in the adjacent Blanche Cave. -

Palaeontology Bibliography for the Naracoorte Caves National Park and World Heritage Area

Palaeontology Bibliography for the Naracoorte Caves National Park and World Heritage Area P = Palaeoecology; T = Taxonomy; D = Depositional setting and dating; S = Species Occurrence within/among sites; PC = Palaeoclimate; Taph = Taphonomy; F = Functional Morphology; IF = Five-year impact factor (as at Sept 2014) Peer-reviewed scientific publications Ashwell, K.W.S., Hardman, C.D. and Musser, A.M. 2014. Brain and behaviour of living and extinct echidnas. Zoology 117, 349–361. (F) IF = 1.6 Ayliffe, L. and Veeh, H.H. 1988. Uranium-series dating of speleothems and bones from Victoria Cave, Naracoorte, South Australia. Chemical Geology (Isotope Geoscience Section) 72, 211–234. (D) IF = 4.4 Ayliffe, L.K., Marianelli, P.C., Moriarty, K.C., Wells, R.T., McCulloch, M.T., Mortimer, G.E. and Hellstrom, J.C. 1998. 500 ka precipitation record from south-eastern Australia: evidence for interglacial relative aridity. Geology 26, 147–150. (PC) IF = 4.9 Bestland, E.A. and Rennie, J. 2006. Stable isotope record (δ 18O and δ13C) of a Naracoorte Caves speleothem (Australia) from before and after the Last Interglacial. Alcheringa Special Issue 1, 19–29. (PC) IF = 1 Bishop, N. 1997. Functional anatomy of the macropodid pes. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 117, 17–50. (F) No IF Boles, W.E. 2008. Systematics of the fossil Australian giant megapodes Progura (Aves: Megapodiidae). Oryctos 7, 191–211. (T) IF = 1.7 Brown, S.P. and Wells, R.T. 2000. A Middle Pleistocene vertebrate fossil assemblage from Cathedral Cave, Naracoorte, South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 124, 91–104. -

Cave and Karst Management in Australasia XX I Proceedings of the 21St Australasian Conference on Cave and Karst Management Naracoorte, South Australia, 2015

Cave and Karst Management in Australasia XX I Proceedings of the 21st Australasian Conference on Cave and Karst Management Naracoorte, South Australia, 2015 Australasian Cave and Karst Management Association 2015 ACKMA Cave and Karst Management in Australasia 21 Naracoorte Caves , South Australia , 201 5 i Proceedings of the Twenty first Australasian Conference on Cave and Karst Management 2015 Conference Naracoorte, South Australia, 2015 Cave and Karst Management in Australasia XXI Australasian Cave and Karst Management Association 2015 ACKMA Cave and Karst Management in Australasia 21 Naracoorte Caves , South Australia , 201 5 ii Cave and Karst Management in Australasia XXI Editors: Rauleigh and Samantha Webb ACKMA Western Australia Publisher: Australasian Cave and Karst Management Association PO Box 27, Mount Compass South Australia, Australia 5210 www.ackma.org Date: August 2015 ISSN No: 0159-5415 Copyright property of the contributing authors: Copyright on any paper contained in these Proceedings remains the property of the author(s) of that paper. Apart from use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand) no part may be reproduced without prior permission from the author(s). It may be possible to contact contributing authors through the Australasian Cave and Karst Management Association Proceedings available: Publications Officer Australasian Cave and Karst Management Assn Cover illustration: Top photo: Fossil Bed (Pit A), Victoria Fossil Cave, Naracoorte Photo by Steve Bourne Bottom photo: Stalactites in Blanche Cave, -

Auckland Like Many Other Lay Enthusiasts, He Made Considerable

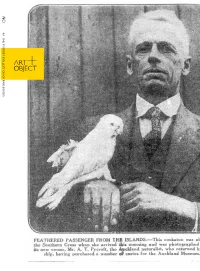

49 THE PYCROFT COLLECTION OF RARE BOOKS Arthur Thomas Pycroft ART + OBJECT (1875–1971) 3 Abbey Street Arthur Pycroft was the “essential gentleman amateur”. Newton Auckland Like many other lay enthusiasts, he made considerable PO Box 68 345 contributions as a naturalist, scholar, historian and Newton conservationist. Auckland 1145 He was educated at the Church of England Grammar Telephone: +64 9 354 4646 School in Parnell, Auckland’s first grammar school, where his Freephone: 0 800 80 60 01 father Henry Thomas Pycroft a Greek and Hebrew scholar Facsimile: +64 9 354 4645 was the headmaster between 1883 and 1886. The family [email protected] lived in the headmaster’s residence now known as “Kinder www.artandobject.co.nz House”. He then went on to Auckland Grammar School. On leaving school he joined the Auckland Institute in 1896, remaining a member Previous spread: for 75 years, becoming President in 1935 and serving on the Council for over 40 years. Lots, clockwise from top left: 515 Throughout this time he collaborated as a respected colleague with New Zealand’s (map), 521, 315, 313, 513, 507, foremost men of science, naturalists and museum directors of his era. 512, 510, 514, 518, 522, 520, 516, 519, 517 From an early age he developed a “hands on” approach to all his interests and corresponded with other experts including Sir Walter Buller regarding his rediscovery Rear cover: of the Little Black Shag and other species which were later included in Buller’s 1905 Lot 11 Supplement. New Zealand’s many off shore islands fascinated him and in the summer of 1903-04 he spent nearly six weeks on Taranga (Hen Island), the first of several visits. -

The Governor-General of New Zealand Dame Patsy Reddy

New Zealand’s Governor General The Governor-General is a symbol of unity and leadership, with the holder of the Office fulfilling important constitutional, ceremonial, international, and community roles. Kia ora, nga mihi ki a koutou Welcome “As Governor-General, I welcome opportunities to acknowledge As New Zealand’s 21st Governor-General, I am honoured to undertake success and achievements, and to champion those who are the duties and responsibilities of the representative of the Queen of prepared to assume leadership roles – whether at school, New Zealand. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the role of the Sovereign’s representative has changed – and will continue community, local or central government, in the public or to do so as every Governor and Governor-General makes his or her own private sector. I want to encourage greater diversity within our contribution to the Office, to New Zealand and to our sense of national leadership, drawing on the experience of all those who have and cultural identity. chosen to make New Zealand their home, from tangata whenua through to our most recent arrivals from all parts of the world. This booklet offers an insight into the role the Governor-General plays We have an extraordinary opportunity to maximise that human in contemporary New Zealand. Here you will find a summary of the potential. constitutional responsibilities, and the international, ceremonial, and community leadership activities Above all, I want to fulfil New Zealanders’ expectations of this a Governor-General undertakes. unique and complex role.” It will be my privilege to build on the legacy The Rt Hon Dame Patsy Reddy of my predecessors.