The Many Dimensions of Aiki Extensions∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aikido in Everyday Life: Giving in to Get Your

Aikido in Everyday Life: Giving in to Get Your Way Aikido in Everyday Life: Giving in to Get Your Way, 1556431511, 9781556431517, Terry Dobson, Victor Miller, 1978, 256 pages, North Atlantic Books, 1978 Conflict is an unavoidable aspect of living. The late renowned aikido master Terry Dobson, together with Victor Miller, present aikido as a basis for conflict resolution. Not all conflicts are contests, say Dobson and Miller, and not all conflicts are equally threatening. Finding more options to deal with conflict can change how we deal with other people. "Attack-tics" is a system of conflict resolution based on the principles of aikido, the non-violent martial art created by master Morihei Ueshiba after World War II.--Adapted from back cover. FILE: http://resourceid.org/2gfDUpT.pdf An Obese White Gentleman in No Apparent Distress, Riki Moss, Terry Dobson, 2009, 324 pages, A novel based on the writings and recordings of Terry Dobson, Fiction, ISBN:158394270X FILE: http://resourceid.org/2gfKzQN.pdf To Rod Kobayashi Sensei, the man who first taught me Aikido and who opened my eyes to The world gets worse every day." "We hardly ever talk anymore." "The things these kids are doing these As we apply the formula daily, our tendency toward a knee-jerk or unconscious. It be yoga in Chennai or yoga in San Francisco, aikido in Islamabad or aikido in Birkenhead likely they are to contribute to the wellbeing of those around them during their daily lives, let alone consumerism is alive and well, if not rampant, within the sphere of inner-life spirituality?. -

(Con)Sequences: Gender, Dance and Ethnicity

Issue 2011 36 (Con)Sequences: Gender, Dance and Ethnicity Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 Editor About Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. -

AIKIDO Vol. I Biografii & Interviuri

AIKIDO Vol. I Biografii & Interviuri 1 Această carte este editată de CS Marubashi & www.aikido-jurnal.ro. Nu este de vânzare 2 Morihei Ueshiba 14 Decembrie 1883 – 26 Aprilie 1969 Privind viața acestuia din toate direcțiile, se poate spune că Fondatorul a trăit ca un adevărat samurai din străvechea și tradiționala Japonie. El a întruchipat starea de unitate cu forțele cosmosului, reprezentând ideea spirituală a artelor marțiale de-a lungul istoriei japoneze. Pe 14 decembrie 1883, în orașul Tanabe din districtul Kii (în prezent prefectura Wakayama), Japonia, s-a născut Morihei Ueshiba, al 4-lea copil al lui Yoroku și Yuki Ueshiba. Morihei a moștenit de la tatăl său determinarea și interesul pentru treburile publice, iar de la mama sa înclinația pentru religie, poezie și artă. Începutul vieții sale a fost umbrit de boli. La vârsta de 7 ani a fost trimis la Rizoderma (o școală particulară a sectei budiste Shingon) să studieze clasicii chinezi și scripturile budiste, dar a fost mai fascinat de poveștile miraculoase despre sfinții En no Gyoja și Kobo Daishi. De asemenea, a avut un extraordinar interes față de meditațiile, incantațiile și rugăciunile acestei secte esoterice. Îngrijorat că tânărul Morihei se supraîncărca mental în căutările sale, tatăl său - un om puternic și viguros - l-a încurajat să-și disciplineze și întărească corpul prin practicarea luptelor sumo precum și a înotului. Morihei a realizat necesitatea unui corp puternic după ce tatăl său a fost atacat într-o seară de o bandă angajată de un politician rival. ................................................................................. 3 Pe 26 aprilie 1969, Marele Maestru și-a terminat viața pământească, întorcându-se la Sursa. -

GOING for a WALK in the WORLD: the Experience of Aikido by Ralph Pettman

GOING FOR A WALK IN THE WORLD: The Experience of Aikido By Ralph Pettman The dream that makes us free is the dream of an open heart the dream that there might be one world lived together while living apart. This calligraphy was done by Shuken Motomiya, an old and much venerated Zen monk. When he did it, he lived in a temple at Fujinomiya, at the foot of Mt. Fuji. The character means “Dream”. A lovely piece of calligraphy that was brushed especially for this book The complete book is about 20,000 words. It is licensed under a Creative Commons license, so please feel free to reproduce it, with due attribution. Ralph Pettman Going For A Walk In The World TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 1 WHAT IS AIKIDO? ....................................................................................................................................... 2 WHAT IS AIKIDO FOR?............................................................................................................................... 5 CUTTING THROUGH SPIRITUAL MATERIALISM\.................................................................................... 8 ENDS AND MEANS ................................................................................................................................... 10 A WAY TO HARMONY WITH THE UNIVERSE......................................................................................... 12 THE PHYSICAL DIMENSION -

Aiki Peace Week

AIKI EXTENSIONS Aiki: Not a set of techniques to conquer an enemy, but a way to reconcile the world and make all of human kind one family - Morihei Ueshiba A Quarterly Newsletter Content Highlights Issue N° 32 Aiki Peace Week Program Updates Seminars Individual Initiatives Online Resources Read about our progress A flurry of activity Details about recent One AE member is Aiki Extensions (87 dojos from 19 surrounding the and upcoming seminars launching a “Bike for connects our members countries) and the Awassa Peace Dojo, our featuring AE members Peace” effort this with Facebook pages, recent endorsement new Aiki Business and topics - Teaching summer. Another is Google Groups, and from Yamada Shihan Group, and a Teen Aikido to Kids, planning a “Peace online tutorials. Get Summit at Brooklyn Training Across Train” itinerary from connected, get involved! In the News Page 1-2 College. Borders, Cultures of dojo to dojo across the Several AE programs Peace, & Body, Heart, US. Where will Aikido and personalities on and Mind take you? TV, radio, and the web Page 3-6 Page 7 - 8 Page 9 Page 9-13 Page 15 Aiki-Peace Lesson Plans It might surprise people outside Aikido that a martial art can teach someone to live peacefully. Aiki Peace Aikido is uniquely equipped for practicing peace because attack/defense drills serve to rouse the twin demons of fear and anger at the same time one Week practices receiving an opponent with kindness, in a harmonious and grounded way. Aikido training gradually makes this reaction into our default International Aiki Peace Week is gathering momentum - The map of participating dojos - Peace Week response in times of stress, conflict, or attack. -

Nadeau Interview

Interview with Robert Nadeau by Stanley Pranin Aikido Journal #117 (1999) Robert Nadeau at 2001 San Rafael Summer Camp Robert Nadeau was 22 years old when he boarded a ship bound for Japan. His odyssey brought him face to face with the founder of aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, who would remain a constant source of inspiration and guidance to the young foreigner. A full-time aikido instructor in Northern California for over 30 years, Nadeau reminisces about his early days in budo and the evolution of his unique body and spiritual training methods. Nowadays when a student walks into an aikido dojo there are likely to be many black belts on the mat. However, when you began there were probably less than five dojos in all of California. I’m not sure what was going on down south in Southern California, but as far as I know there was only one school in Northern California which was run by Robert Tann. I wasn’t very connected with the Los Angeles area to know what was going on, although I do remember meeting Francis Takahashi around early 1962. I guess you didn’t train with Robert Tann very long before going to Japan… No, not very long. I was grateful for the opportunity that he provided me to start training. He reminded me at his retirement dinner that it was at my insistence that he continued to operate a dojo and teach. So you received your first dan rank in Japan? Yes. You mentioned a very interesting episode where you had a dream in which a little old man with a white beard appeared and went to see a psychic about it… It’s an oft told story. -

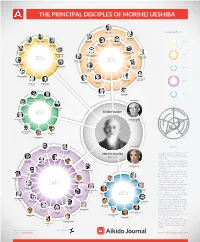

Osensei Disciples Chart FINAL Color Alt2

THE PRINCIPAL DISCIPLES OF MORIHEI UESHIBA Koichi Tohei VISUALIZATION 1920-2011 Kenzo Futaki 1873-1966 Isamu Takeshita Minoru Hirai 1920 1869-1949 1903-1998 Seikyo Asano Kaoru Funahashi Kenji Tomiki Saburo Wakuta 1867-1945 c1911-unknown 1900-1979 1903-1989 Yoichiro Inoue Shigemi Yonekawa 1902-1994 1910-2005 1930 Kosaburo Gejo Shigenobu Okumura c1862-unknown 1922-2008 Rinjiro Shirata 20’s 1912-1993 Bansen Tanaka 30’s 1912-1988 Aritoshi Murashige 1895-1964 Makoto Miura Kiyoshi Nakakura 1940 1875-unknown 1910-2000 Kenji Tomita 1897-1977 Minoru Mochizuki 1907-2003 Takako Kunigoshi Tsutomu Yukawa 1911-c2000 1950 c1911-1942 Takuma Hisa Zenzaburo Akazawa Hajime Iwata Hisao Kamada 1895-1980 1919-2007 1909-2003 1911-1986 Gozo Shioda 1960 Yoshio Sugino 1915-1994 1904-1998 Kanshu Sunadomari Tadashi Abe 1923-2010 1926-1984 Second Doshu Kisaburo Osawa 1920 25 1911-1991 Morihiro Saito 1928-2002 Aikido Founder 20 40’s 15 10 1960 1930 Hirokazu Kobayashi Kisshomaru Ueshiba 5 1929-1998 1921-1999 Sadateru Arikawa 1930-2003 Hiroshi Tada 1929- Hiroshi Isoyama 1950 1940 1937- Present Doshu NOTES Michio Hikitsuchi * 1923-2004 Seigo Yamaguchi 1924-1996 • This chart presents the major disciples of Morihei Ueshiba Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba during his 1883-1969 teaching career which spanned the period of 1920 to 1969. Shoji Nishio • The visualization is a graphical representa- 1927-2005 Masamichi Noro 1935-2013 tion of the number of disciples referenced in Seiseki Abe this chart, but is not a statistical analysis of Shuji Maruyama 1915-2011 Moriteru Ueshiba the complete roster of the direct disciples of 1940- 1951- the Founder. -

Dojo Expansion and Dojo Spirit

Winter / Spring 2009 Newsletter / Aikido Institute Davis Awase Ranks in Aikido Awase is the newsletter of the Aikido Institute of Davis, a dojo where the by Hoa Newens, Sensei arts of Aikido and Tai Chi are instructed. Going through the ranks is an integral part of the Please visit our website at Aikido experience. An adult student typically AikidoDavis.com for information on begins at the rank of 6th Kyuu and undergoes a membership & class times. series of exams during the next three to five (four on average) years of training to get to the end of 1st Kyuu. Thereafter one takes the exam for the rank of Shodan (translated as “beginning grade”), also known as black belt first degree. The Kyuu grades are in effect a countdown to the rank of Shodan. In this way the first four years of Aikido training in Kyuu grades are viewed as preparatory training for the journey that begins with Shodan. Thereafter, one progresses through the ranks of Nidan (2nd degree), Sandan (3rd degree), Yondan (4th degree), etc. The top dan grade of Judan (10th degree) is held only by a handful of people in the world who are outstanding exponents of the art. This journey can take several decades and last till the end of our life. The rank of Shodan thus denotes a significant threshold indicating that the student is now ready to receive, or deserving of, the full Aikido teaching; in other words, Shodan is when one begins the study of Aikido in earnest. In the old times, Japanese martial arts students did not get ranks. -

Aiki Business Group Primer

Aiki Business Group Mission: Bring aikido principles and embodiment practices into the business world Vision: Establish a network of experienced, successful practitioners to advise and enable others interested in bringing Aikido into the business world Strategic Goals • Establish a catalog of practitioners and their links from around the world • Establish a social network / interactive WIKI on the AE website • Plan and conduct a conference for experienced and new practitioners • Develop an online How-To Manual that provides: o Guidelines on how to successfully engage with businesses o Case studies of successful service projects to business o A process guide that explains how to market, price, sell, contract for, implement and evaluate consulting, coaching and training services o A process guide that describes example seminars, lists potential training exercises, example sequences and their facilitation o Recorded interviews, articles and book excerpts from pioneers o A video archive of seminars provided by experienced practitioners o An annotated bibliography of training centers, seminars, books, articles and videos in the field The History of the Work The applications of Aikido principles to the world of business cover a wide spectrum. The work ranges from business leaders who have trained in the art and then discovered natural connections to the way they do business, to Aikido teachers who have developed presentation, consulting and training businesses that contract with individual professionals, organization leaders, corporations and non profits to help them improve their performance. The Basic Approach Historically, the primary approach of both the consultants and trainers has been to demonstrate Aikido and its core principles as a context and then provide, slow motion, non falling exercises drawn directly from mat practice to establish an experiential, embodied understanding of those principles and a physical simulation of their application to business life. -

Aikido Times March/April 2014 the OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER of the BRITISH AIKIDO BOARD 2013 Welcome

Aikido Times March/April 2014 THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE BRITISH AIKIDO BOARD www.bab.org.ukDECEMBER 2013 Welcome... Featured to the April issue of the Aikido Times. articles Yet again we have a packed issue, full of articles and event information. “The times they are a changing” page 2 My thanks to all of you who have sent in articles for publication. If your article hasn’t been included this BAB Insurance explained page 4 time it is being held over for another issue. Aikido as an effective When submitting something for publication please defence art endeavour to send in some pictures or illustrations page 6 to go with your article (make sure you have permission to use photographs). Aikido Times: old and new The next issue will be published on 16th June with a cut off date for submissions page 13 on the 11th June Let wisdom be the hero If you have any items to submit then please contact me at: page 14 [email protected] Brian Stockwell, Editor Instructor Profile: Richard Lewis page 16 Application of philosophy in the martial arts page 19 Horse riding and aikido page 21 Reflections on Aikido and Dance page 22 FORWARD TO March/ April 2014 A FRIEND CLICK HERE TO RECEIVE THE AIKIDO TIMES “The times they are a changing” THE BAB’S NEW CHILD Piers Cooke: BAB Finance Officer SAFEGUARDING WEB SITE Never in the aikido world has the above lyric The BAB’s Lead Safeguarding been more accurate. I have been the finance Officer has created a new ‘mini’ officer of the BAB for the last 12 -13 years and in website within the BAB’s main web that time I have watched the aikido community site. -

CRA Handbook 2021-May

Castle Rock AIKIDO Student Handbook …a physical path to self-mastery © 2007-2021 Castle Rock AIKIDO, All Rights Reserved. Mission Statement Our mission is… “to forge in our students a strength of character so strong, that conflict becomes unnecessary.” Many assume that the “conflict” we refer to in this mission statement is physical conflict, such as fighting with others. However, the conflict we mean to emphasize is inner conflict - the mental, emotional and even spiritual conflict most of us struggle within each and every day. Through the practice of Aikido we discover within ourselves a physical path to self-mastery… What is Aikido? “True victory is self-victory.” – Morihei Ueshiba Aikido is a powerful martial art developed throughout the mid-20th century by a Japanese man named MORIHEI UESHIBA. Aikido differs from most other martial arts in that the practitioner seeks to achieve self-defense without necessarily seriously injuring his or her attacker(s). Furthermore, Aikido is non-competitive and, therefore, there are no tournaments or sport applications in Aikido. Generally speaking, Aikido is most often practiced with a partner where one person functions as an attacker (UKE) and the other person practices defensive Aikido techniques (NAGE). About half of Aikido’s techniques involve joint locks which enable the partner or "attacker" to be moved to a pinning position where they can be held without serious injury. Other techniques involve throwing one’s partner to the ground. An Aikido student spends a great amount of time learning how to fall safely. Proper falling is a fundamental skill to the practice of Aikido. -

Student Handbook …A Physical Path to Self-Mastery

Castle Rock AIKIDO Student Handbook …a physical path to self-mastery © 2007-2019 Castle Rock AIKIDO, All Rights Reserved. Mission Statement Our mission is… “to forge in our students a strength of character so strong, that conflict becomes unnecessary.” Many assume that the “conflict” we refer to in this mission statement is physical conflict, such as fighting with others. However, the conflict we mean to emphasize is inner conflict - the mental, emotional and even spiritual conflict most of us struggle within each and every day. Through the practice of Aikido we discover within ourselves a physical path to self-mastery… What is Aikido? “True victory is self-victory.” – Morihei Ueshiba Aikido is a powerful martial art developed throughout the mid-20th century by a Japanese man named MORIHEI UESHIBA. Aikido differs from most other martial arts in that the practitioner seeks to achieve self-defense without necessarily seriously injuring his or her attacker(s). Furthermore, Aikido is non-competitive and, therefore, there are no tournaments or sport applications in Aikido. Generally speaking, Aikido is most often practiced with a partner where one person functions as an attacker (UKE) and the other person practices defensive Aikido techniques (NAGE). About half of Aikido’s techniques involve joint locks which enable the partner or "attacker" to be moved to a pinning position where they can be held without serious injury. Other techniques involve throwing one’s partner to the ground. An Aikido student spends a great amount of time learning how to fall safely. Proper falling is a fundamental skill to the practice of Aikido.