Interview with Alan Vega and Martin Rev Aka Suicide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: a New York City Story Online

EoeUa [Download] Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story Online [EoeUa.ebook] Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story Pdf Free Kris Needs ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1025856 in eBooks 2015-10-12 2015-10-18File Name: B0100QGEGW | File size: 55.Mb Kris Needs : Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Dream Baby Dream: Suicide: A New York City Story: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Nice overview of New York City when it was a ...By John J. PotterNice overview of New York City when it was a dangerous creative cauldron of activity. Furthermore, Harrry Hill supplies insightful writing that adds resonance to Suicide's musical contributions to the period and the history of electronic music. BUY their first album and this tome!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A history of New York's musical art world in the 70'sBy Timm DavisonA great read0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. True originals. True story.By CustomerFantastic. ldquo;We were living through the realities of war and bringing the war onto the stage... Everybody hated us, manrdquo; Alan Vega Born out of the city's vibrant artistic underground as a counter-cultural performance art statement, opposing the war by mirroring its turmoil, Suicide became the most terrifyingly iconoclastic band in history, and also one of the most influential. -

The Blank Generation

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The Blank Generation (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Akron 1976-80 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The "blank generation" came out of a moral vacuum. While punks roamed the suburban landscape, blue-collar workers were feeling the pinch of an economic revolution: human society had left the industrial age and entered the post-industrial age, the age in which services (such as software) prevail over manufacturing. Computers now rule the world, from Wall Street to Boeing. The assembly line took away a bit of the personality of the worker, but that was nothing: the new service- based economy takes away the worker completely, physically. In the post-industrial society the individual is even less of a "person". The individual is merely a cog in a huge organism of interconnected parts that works at the beat of a gigantic network of computers. This highly sophisticated economy treats the individual as a number, as a statistic. The goal is no longer to create a robot that behaves like a human being, but to create a human being that behaves like a robot: robots are efficient and lead to manageable and profitable businesses, whereas humans are inefficient and difficult to manage. -

Martin Rev Cheyenne

MARTIN REV CHEYENNE Reissue (originally released 1991) CD / vinyl / digital Out: June 21, 2019 Label: Bureau B Although it was not released until 1991, Martin Rev’s third Cat no. BB 317 solo album features a wealth of material from the year 1980. Distributor: Indigo For “Cheyenne”, Rev created instrumental versions of Vinyl EAN / order no.: many of the tracks which had formed the basis of the se - 4015698027259 / 166261 cond Suicide LP entitled “Alan Vega / Martin Rev”. CD EAN / order no.: 4015698027235 / 166262 The sphere of Martin Rev’s influence and the relevance of his music may well be related to the fact that he was one of the first Tracklisting artists who succeeded in grasping the abstraction of electronic 1 Wings of the Wind (7:58) music, infusing it with a sense of immediacy built on raw energy. 2 Red Sierra (6:36) Whilst the likes of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, 3 Dakota (2:58) Philip Glass and Kraftwerk were busy digging in the electronic 4 Cheyenne (3:09) music garden, Martin Rev found inspiration in the streets of New 5 River of Tears (3:49) York. Rev’s music is informed by characteristic influences of the 6 Buckeye (2:15) city, a place where doo-wop harmonies intermingle with the hiss 7 Little Rock (7:00) and hum of the metropolis, dissolving into a collage of noise. 8 Prairie Star (2:27) 9 Mustang (2:40) So it is that dreamy, chiming melodies blur into ominous whirrs 10 Pony (1:55) Bonus and drones emanating from rhythm machines and layers of dis - 11 Durango (2:21) Bonus torted synthesizer. -

Martin Rev Clouds of Glory

MARTIN REV CLOUDS OF GLORY Reissue (originally released 1985) CD / vinyl / digital Out: June 21, 2019 Label: Bureau B Martin Rev is best known as one half of the seminal duo Cat no. BB 316 Suicide (with Alan Vega). Listening to his solo albums, it Distributor: Indigo becomes clear that Rev was responsible for the group’s music. Clouds of Glory, his second solo effort, was re - Vinyl EAN / order no.: leased on the French label New Rose in 1985. 4015698027204 / 166251 Suicide mirrored the reductive and radical traits of the contem - CD EAN / order no.: poraneous punk scene that was in the process of emerging, but 4015698027181 / 166252 their electronic, minimalist form of language was so unique, so innovative, that they would become a major influence on the likes of Daft Punk, Air and Aphex Twin. Tracklisting Alongside his work with Suicide, Martin Rev continued as a solo 1 Rocking Horse (5:45) artist, releasing his eponymous debut album in 1980 on New 2 Parade (6:45) York’s Infidelity label. Rev’s early solo excursions can be traced 3 Whisper (4:04) back to the original ideas which can be found – in modified form – 4 Rodeo (6:37) in Suicide songs: as instrumental versions which have been tex - 5 Metatron (6:25) turally enriched, like a familiar figure which has nevertheless 6 Clouds Of Glory (6:22) taken on a completely new existence. Five years later, in 1985, Martin Rev released his sophomore Promo solo LP on the Parisian label New Rose Records, although the Bureau B recordings on Clouds Of Glory actually dated back to the earlier Matthias Kümpflein part of the decade, following on from the Suicide sessions for Tel 0049-(0)40-881666-63 the duo’s second album. -

Vinyl Continuity Being the Queues to Collector Record Cover Versions

spanned an often balladic broad ★ musical palette – the main Vinyl continuity being the queues to Collector record cover versions. by Paul Rigby This 25-track compilation of career highlights is packed with classics, starting with The Troggs (who also covered Anyway That You Want Me – here by Tina Mason) and ending with Taylor’s later forays into country music. In between there are timeless gems such as Out Of Focus debut, Wake Up, which owed more outspoken and Lorraine Ellison’s Try (Just A Wake Up a debt to early UK prog targeted, highlighting religion Little Bit Harder) (later huge for ★★★ outfits, weaving improvised as a particular cause célèbre. Janis Joplin), Merillee Rush’s Sandy Denny Missing Vinyl MV 004 passages through Its follow-up, Four Letter Angel Of The Morning and She Moves Through The Out Of Focus conventional song structure. Monday Afternoon, released Picture Me Gone – originally a Fair ★★★★ The weakest of the three, the same year, presented a hit for Taylor’s protégé Evie ★★★ Missing Vinyl MV 006 Wake Up is, however, still a full-on Soft Machine-like jazz- Sands (present with I Can’t Let Stamford Audio STAMPLP 1003 Four Letter Monday recommended listen, thanks rock fusion, with avant-garde Go) and covered sublimely here Conventional release for the Afternoon to its funk-based grooves touches and more extended by the often-overlooked hardcore fan ★★★★ and a lyrical depth that instrumental experiments. Madeline Bell. Recorded by Denny when she Missing Vinyl MV 005 (2-LP) reflected social and political Across the double album Out Other names include Aretha was just 19 years old, this Lens your ears to this ideas without hitting you over Of Focus, the group were able Franklin, Peggy Lee, Billy Vera, limited, 500-only EP consists prog barrage the head with its tenets. -

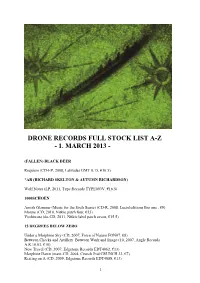

13-03-01 Full Stock List

DRONE RECORDS FULL STOCK LIST A-Z - 1. MARCH 2013 - (FALLEN) BLACK DEER Requiem (CD-EP, 2008, Latitudes GMT 0:15, €10.5) *AR (RICHARD SKELTON & AUTUMN RICHARDSON) Wolf Notes (LP, 2011, Type Records TYPE093V, €16.5) 1000SCHOEN Amish Glamour (Music for the Sixth Sense) (CD-R, 2008, Lucioleditions llns one , €9) Moune (CD, 2010, Nitkie patch four, €13) Yoshiwara (do-CD, 2011, Nitkie label patch seven, €15.5) 15 DEGREES BELOW ZERO Under a Morphine Sky (CD, 2007, Force of Nature FON07, €8) Between Checks and Artillery. Between Work and Image (10, 2007, Angle Records A.R.10.03, €10) New Travel (CD, 2007, Edgetone Records EDT4062, €13) Morphine Dawn (maxi-CD, 2004, Crunch Pod CRUNCH 32, €7) Resting on A (CD, 2009, Edgetone Records EDT4088, €13) 1 21 GRAMMS Water-Membrane (CD, 2012, Greytone grey009, €12) 23 SKIDOO The Culling is Coming (CD, 2003, LTM Publishing / Boutique BOUCD 6604, €15) Seven Songs (CD, 2008, LTM Publishing LTMCD 2528, €14.5) Seven Songs (do-LP, 2012, LTM Publishing LTMLP 2528, €29.5) 2KILOS & MORE 9,21 (mCD-R, 2006, Taalem alm 37, €5) 8floors lower (CD, 2007, Jeans Records 04, €13) 3/4HADBEENELIMINATED The Religious Experience (LP, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 147, €25) Theology (CD, 2007, Soleilmoon Recordings SOL 148, €19.5) Oblivion (CD, 2010, Die Schachtel DSZeit11, €14) 400 LONELY THINGS same (LP, 2003, Bronsonunlimited BRO 000 LP, €12) 5F-X The Xenomorphians (CD, 2007, Hands Production D112, €15) 5IVE Hesperus (CD, 2008, Tortuga TR-037, €16) 5UU'S Crisis in Clay (CD, 1997, ReR Megacorp ReR 5uu2, €14) Hunger's Teeth -

1993.02.20-NME.Pdf

that there was a ful! Maori choir, an English brass band and some Cook Island drummers all playing at the same time with the chi Idren EUROPE ofthe Maori choir all running around outside. It was bizarre enough to make the local papers, but in reality this was just another day in the studio with an acid house producer, says Mr Weatherall. Next SABRES OF PARADISE releases will be 'Musical Science’ FINITRIBE are releasing their by MUSICAL SCIENCE (out first single for eight months on now) a new WAXWORTH their own label following a dispute INDUSTRIES called Take The Finitribe: unleashing a ‘Monster’ on their own label with record company One Little Book’, something choc-a-bloc full Indian, as told in last week's have a shot at putti ng out our own their product." of spoken samples from Suicide’s Flyers. records. That can’t be too much to Incidentally, 'Forevergreen'was Alan Vega entitled 'Vega God’ The house trio have clashed with ask.” the highest new entry on the US (mid-March) by "we don’t know the indie over the unreleased track It is not a permanent split, Billboardchart last week. what he’s gonna cal l himself yet" 'Meliowman', which One Little however, says Miller. Finitribe. You can hear DAVEY and another track entitled ‘Blue', Indian refused to release in its who are continuing to negotiate FINITRIBE discussing the issue “that’s all we know about it at the original form. They say the label with One Little Indian, simply want with a representative of One Little moment”. -

Ocln 530 Radioeins Datum: 25.07.2009 Oceanclub Latenite 530 1:00 Bis 05:00 Gudrun Gut Redaktion: G.Gut + Thomas Fehlmann

ocln 530 radioeins Datum: 25.07.2009 oceanclub LateNite 530 1:00 bis 05:00 gudrun gut Redaktion: g.gut + thomas fehlmann TITEL* INTERPRET* ALBUM BEMERKUNGEN NACHRICHTEN a www.radioeins.de OCEANCLUB JINGLE Begin www.oceanclub.de everytime SKIT j. dilla yancey boys instrumentals www.myspace.com/jdilla the last and least likely ribbons royals www.osaka.ie fools the dodos visiter www.dodosmusic.net take off my shirt vincent it's only wasteland, mum! www.blankrecords.de the walk (poponame mix) andreas heiszenberger ep www.polytone-music.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de hard boiled babe lizzy mercier descloux va: ze 30 - ze records 1979-2009 www.zerecords.com jukebox babe alan vega va: ze 30 - ze records 1979-2009 www.zerecords.com drops of color green sky accident drops of color www.interregnumrecords.com butterfly envy delicate noise filmezza www.lensrecords.com OCEANCLUB JINGLE www.oceanclub.de the bone song the sa-ra creative partners nuclear revolution - the age of love www.ubiquityrecords.com eid ma clack shaw bill callahan sometimes i wish we were an eagle www.dragcity.com roll on babe vetiver things of the past www.fat-cat.co.uk not leaving town patrick kelleher you look cold www.osaka.ie teen diethylamide25 the rational academy swans www.someonegood.org 12 feet in cheltenham the rational academy swans www.someonegood.org NACHRICHTEN b www.radioeins.de CIO D'OR OC MIX www.ciodor.de starlight - intrusion dub model 500 va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de cv313 reduction 2- vantage isle deepchord va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de reduction echospace va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de dc mix3 - vantage isle deepchord va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de zap - norman nodge mix (coming homeandre ep) lodemann va: CIO D'OR mix www.ciodor.de rever.. -

The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGB's Explores the Intersection of Jewish

For Release: October 2006 Contact: Sara Hoerdeman Publicity Manager Independent Publishers Group (312) 337-0747 ext. 236 [email protected] **digital cover image available** The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGB’s explores the intersection of Jewish identity and punk rock **Jewish-owned punk landmark, CBGB, will close on October 1, 2006** CHICAGO: On October 1, 2006, CBGB will shut its doors for good. The little Lower East Side Jewish-owned club became the center of the New York City punk scene, and on the eve of its closing, a new book examines its role, and that of Jews in the punk movement. The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGB’s: A Secret History of Jewish Punk (Chicago Review Press, October 2006) by Steven Lee Beeber delves into punk’s beginnings in New York City and discovers it to be the most Jewish of rock movements, both in makeup and attitude. The Heebie Jeebies at CBGB’s offers a fascinating mix of biography and cultural study that explores the lives of Jewish punks and creates an in-depth historical overview of the punk scene. In the early 1970s, from in and around New York, came a rag-tag assortment of young people. They came from a wide range of backgrounds, from comfortable and conservative middle class families to poor and immigrant origins, but despite their differences, they all had something burning inside. Fueled by the humor of Lenny --more-- Bruce—and more strongly influenced by their Jewish heritage than even they knew— they emerged, raw, ambitious and ready to rock, into the New York scene and changed music forever. -

Bristol Archive Special

Bristol Archive Special lssue 12 still only t1 ! New interviews with THE CORTINAS, SOCIAL SECURITY' The X-CERTS and THE PIGS plus VALDEZ and the CUT UpS as well a farewell tribute to the Junction This issue we celebrate the fine work done by Graham at Crime Scene, Matt at Mike Darby and his team at BristolArchive Deadpunk, Jesse Eastfield, Sean at Records. We have new interviews with four Jamdown, Kevin at Do The Dog, bands featured on the label, plus a round-up Simon at Trash City, Welly at Artcore; of BAR releases in our review section. UTl, Hacksaw, the Zatopeks, the Elsewhere, we pay tribute to, and mourn the Hunckbacks, the Setbacks, 7 Crowns, passing of the Bristol Junction. We all thank Jo, Jake and Louie Baldwin; allthe Bob for countless great nights. fanzines that sent us copies to review, and, as tradition dictates, anyone Where to find stuff we've forgotten. lnterviews Cheers to the following fine folk for Page 3 The Cortinas stocking Everlong: Dave @ the Page 5 Social Security Thunderbolt, Ben @ Kebele, Spillers Page 8 The Pigs (Cardifi), Punker Bunker (Brighton), Page 11 The X-Certs Out Of Step (Leeds), Punk Core Distro Page 13 Valdez (New York). And of course if any other Page 18 The Cut Ups shops/distros would care to help out, please get in touch. Reviews Page 21 CDs Where to find us Page 26 Fanzine review Dave Lown Page 27 Farewell to the Junction 7 Nicholas Lane Page 34 Live round up St George Bristol BS5 8TY Editors: Shane & Dave Shane Baldwin The Regular Contributors: Ed UTl, Roger 1 Shilton Close Salter, Dave Patton, James Smith and Dave Kingswood Spiller. -

(税抜) URL 27 Let the Light In

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 27 Let The Light In PTCD1005 CD ROCK/POP 1,050 https://tower.jp/item/1108715 27 ブリトル ディヴィニティ(+BT) SKMN9 CD ROCK/POP 1610 https://tower.jp/item/2897184 44 When Your Heart Stops Beating B000775402 CD ROCK/POP 945 https://tower.jp/item/2131775 1981 Antems For Doomed Youth VOX4 CD ROCK/POP 972.3 https://tower.jp/item/3558774 1984 Rage with No Name DRR023 CD ROCK/POP 1,445 https://tower.jp/item/4619808 !!! アズ イフ(+1) BRC481 CD ROCK/POP 1,478 https://tower.jp/item/3968983 !!! Shake The Shudder <初回限定生産盤> [CD+Tシャツ(Mサイズ)] BRC545TM CD ROCK/POP 3,850 https://tower.jp/item/4478130 !!! Wallop(金曜販売開始商品/LP) WARPLP302 Analog ROCK/POP 2023 https://tower.jp/item/4926114 (((Vluba))) Exile to Another Dimension MA16 CD ROCK/POP 1,050 https://tower.jp/item/4495959 ******** [The Drink] The Drink [********](UK) WEIRD105CD CD ROCK/POP 1673 https://tower.jp/item/4662908 ...And You Will Know Us By The Trザ センチュリー オブ セルフ PCD93218 CD ROCK/POP 1610 https://tower.jp/item/2519319 //Tense// メモリー CLTCD2011 CD ROCK/POP 1610 https://tower.jp/item/3060236 @ L'URLO INTERISTA (JP) GAR2 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809822 @ GRAZIE ROMA (JP) GAR3 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809823 @ IL MEGLIO DI MUSICA & GOAL VOL (JP) GRO15 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809832 @ GRANDE FIORENTINA (JP) GRO12 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809829 @ GENOA NEL CUORE(JP) GAR13 CD ROCK/POP 1,750 https://tower.jp/item/809830 @ URRA' SAMPDORIA! (JP) GRO14 CD ROCK/POP 1,500 https://tower.jp/item/809831 @ ナイトクラブ スプラッシュ NACL1159 -

Alan Vega R.I.P

ALAN VEGA R.I.P. 1938 - 2016 drummer and there may have been a keyboard. “Fireball” was cut short on the Alan Vega of the influential band Suicide as tape - seems that whoever was running ALAN VEGA died in his sleep on July 16, 2016. The singer the tape deck just stopped the recording; was 78 years old. Henry Rollins broke the I don’t know how much was lost. Alan news on his website with a statement from was annoyed because he thought it the Vega family. Vega formed Suicide, the wasn’t loud enough and he complains trailblazing electronic duo, with multi- about it a couple of times. instrumentalist Martin Rev in 1970. The two built a loyal following among the This cassette was given to me shortly New York City punk scene of the early and after the show by a friend/co-worker of mid-1970s, counting such acts as the New mine who was part of the soundcrew - it York Dolls and Iggy Pop and the Stooges could be from the monitor board; it’s as contemporaries and friends. The band’s possibly the master tape but since I’m 1977 self-titled debut is widely considered not certain, call it “unknown generation”. as one of the seminal albums of electronic I might have played it once but I don’t music, released during what was only a remember it and I just found it in one of nascent scene at the time. - Billboard my old boxes of roadie debris, still sealed in it’s broken case with the crumbling + + + + + duct-tape I wrapped it in back in the day.