The Role of Seabirds in Hawaiian Subsistence: Implications for Interpreting Avian Extinction and Extirpation in Polynesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Metabolic Rate of Laysan Albatross and Bonin Petrel Chicks on Midway Atoll!

Pacific Science (1984), vol. 38, no. 2 © 1984 by the University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Metabolic Rate of Laysan Albatross and Bonin Petrel Chicks on Midway Atoll! 2 2 GILBERT S. GRANT ,3 AND G. CAUSEY WHiTTOW ABSTRACT: The resting metabolic rates ofLaysan albatross and Bonin petrel chicks of known age were measured on Midway Atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. The mass-specific metabolism peaked at hatching and then declined to adult levels in Laysan albatross nestlings . The mass specific metabolism of hatchling Bonin petrels was similar to that of adults, but it tripled shortly after hatching. Fasting and feeding episodes affected day-to-day changes in petrel chick metabolism. THE RESTING METABOLIC RATES of chicks rep METHODS resent the major part of their energy expen diture, as they do not fly and their level of The metabolic rates of Laysan albatross activity .is generally low (Blem 1978). The chicks ofknown age on Sand Island, Midway metabolic rate increases as the chick grows Atoll (28°13' N, 177°23' W) were measured in but the relationship between metabolic rate a building immediately adjacent to the nesting and body mass var ies during growth, the par sites. The chicks were placed in a small plexi ticular pattern of variation depending on a glas chamber or in an air-tight wooden box number of factors (Ricklefs 1974). In the (0.7 m on all sides), depending on the size of Procellariiformes, which have relatively long the chick. In the latter instance, a plexiglas nestling periods, the metabolic rate of grow cover allowed observation during a series of ing chicks is known only for Leach's storm measurements. -

Egg Dimensions and Shell Characteristics of Bulwer's Petrels, Bulweria Bulwerii, on Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands!

Pacific Science, vol. 54, no. 2: 183-188 © 2000 by University of Hawai'i Press. All rights reserved Egg Dimensions and Shell Characteristics of Bulwer's Petrels, Bulweria bulwerii, on Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands! 2 3 2 G. C. WmTTow • AND T. N. PETrn ABSTRACT: Measured values for Bulwer's Petrel eggs and eggshells from Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, were within 10% of predicted values available in the literature. In the absence of published predictive equa tions for egg volume, fresh-egg contents, and total functional pore area of the shell, in Procellariiformes, new logarithmic relationships were developed for tropical Procellariiformes. Data are now needed for species breeding at higher latitudes to determine if these relationships are representative of all Procellarii formes. BULWER'S PETREL IS a small, procellariiform placing the air ill the aircell with distilled seabird of the tropical Atlantic, Pacific, and water (Grant et al. 1982a). Egg volumes were Indian Oceans (Warham 1990, Megyesi and measured by weighing the eggs in air and in O'Daniel 1997). In the Hawaiian Archipel water (Rahn et al. 1976). Shell weight and ago, it breeds on islands from Pearl and shell thickness were determined on shells that Hermes Reef in the Northwestern Hawaiian had been dried in a desiccator for at least 3 Islands, to offshore islands of Hawai'i in the days. Shell weight was measured by weighing main Hawaiian Islands (Harrison 1990). the dried shells on a Mettler balance (Model Previously, data were presented for, inter H6) to the nearest 0.1 mg. Shell thickness was alia, the incubation period and the incuba determined with micrometer calipers (Starrett tion weight loss of eggs on Manana, a small No. -

Midway Seabird Protection Plan Story

Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. Midway Seabird Protection Plan – Draft Environmental Assessment Learn About the Emerging Threat Welcome to Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. Midway Atoll is 1,200 miles northwest of Honolulu near the end of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. It is inside one of the largest protected areas in the world. This tiny atoll is home to over 3 million seabirds. And the world's largest colonies of Laysan and Black-footed albatross. Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. But in 2015, a new threat emerged. Midway Seabird Protection Plan - Draft Environmental Assessment The information on this website is intended to supplement the official draft environmental assessment, not replace it. For the official record of documents and findings, please visit https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll. Warning: Some of the following content is disturbing and contains images of dead and wounded albatross. Link to Video with Matt Brown Mice were attacking adult albatross as they sat on their nests - essentially eating the birds alive. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Climate Change and Seabirds of the California Current and Pacific Islands Ecosystems: Observed and Potential Impacts and Management Implications

Climate Change and Seabirds of the California Current and Pacific Islands Ecosystems: Observed and Potential Impacts and Management Implications Final Report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 1 Lindsay Young Pacific Rim Conservation Honolulu, Hawaii Robert M. Suryan Oregon State University Newport, Oregon David Duffy University of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii William J. Sydeman Farallon Institute Petaluma, California 3 May 2012 1 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Climate Change and Seabirds ................................................................................................................... 6 Geographic Scope ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Natural Climate Variability and North Pacific Ecosystems........................................................................ 8 The California Current ................................................................................................................................... 9 Climate Change factors ........................................................................................................................... 10 Atmospheric circulation ..................................................................................................................... -

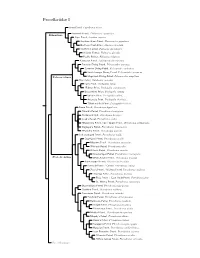

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Breeding Biology of Tristram's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma Tristrami at French Frigate Shoals and Laysan Island, Northwest Hawaii

McClelland et al.: Tristram’s Storm-Petrel breeding biology 175 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF TRISTRAM’S STORM-PETREL OCEANODROMA TRISTRAMI AT FRENCH FRIGATE SHOALS AND LAYSAN ISLAND, NORTHWEST HAWAIIAN ISLANDS GREGORY T.W. McCLELLAND,1,2 IAN L. JONES,1 JENNIFER L. LAVERS1,3 & FUMIO SATO4 1Department of Biology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland, A1B 3X9, Canada 2Current address: Center for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland, 7602, South Africa ([email protected]) 3Current address: Department of Zoology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001, Australia 4Bird Migration Research Center, Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, Konoyama, Abiko, Chiba, 270-1145, Japan Received 2 September 2007, accepted 1 October 2008 SUMMARY MCCLELLAND, G.T.W., JONES, I.L., LAVERS, J.L. & SATO, F. 2008. Breeding biology of Tristram’s Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma tristrami at French Frigate Shoals and Laysan Island, Northwest Hawaiian Islands. Marine Ornithology 36: 175–181. We investigated Tristram’s Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma tristrami on Laysan Island and French Frigate Shoals, Northwest Hawaiian Islands, in the first detailed study of this species’ breeding biology. Breeding extended through the boreal winter from mid-October to mid-June. The mean hatching success on Laysan Island was 0.35 in 2004 and 0.46 in 2005; on Tern Island, it was 0.53 in 2005 and 0.61 in 2006. Fledging success was 0.45, and breeding success 0.16 at Laysan in 2004. At Tern Island, mean fledging success during 2005–2008 was 0.48 (range: 0.47 to 0.51) and overall breeding success in 2005 and 2006 was 0.27 and 0.28 respectively. -

Barau's Petrel Pterodroma Baraui, a New Species for Australia

VOL. 13 (2) JUNE 1989 39 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1989, 13, 39-43 Barau's Petrel Pterodroma baraui, a New Species for Australia by MIKE CARTER', TIM REID2 and PETER LANSLEY3 130 Canadian Bay Road, Mt Eliza, Victoria 3930 2Flat 2/61 Fawkner Street, St Kilda, Victoria 3182 3Flat Tl/99 Epsom Road, Ascot Vale, Victoria 3032 Summary Barau's Petrel Pterodroma baraui can now be added to the Australian Jist. An observation by a group of observers in Victorian waters in February 1987 is documented. This occurrence is discussed in relation to the Indian Ocean distribution of this species and to subsequent observations off Western Australia. The observation On 15 February 1987 at 0945 h (GMT + 11 hours), a Barau's Petrel Pterodroma baraui was observed at sea off western Victoria. All sixteen participants in a group seabird excursion aboard a 13.0 m long fishing boat saw the bird as it came to within 50 m of the stationary vessel lying at 38 "32'S, 141 "1.7 'E. This is some 12.5 nautical miles south-west of Cape Bridgewater and towards the edge of the continental shelf at a water depth of 155 m (85 fathoms). As there was a reasonable concentration of birds at this location, we had stopped the boat to determine the abundance and range of species present. We attracted the birds to the boat by berleying with fish scraps and fresh meat fat doused in cod liver oil. The congregation consisted of c. 25 Black-browed Albatrosses Diomedea melanophris, c. 25 Yellow-nosed Albatrosses D. -

Cookilaria Petrels in the Eastern Pacific Ocean: Identification and Distribution

SCIENCE msspecimens. We scoredcharacters includingmantle color, tail pattern, andhead pattern; sketched head and rectrixpatterns; and took measure- COOKILARIAPETRELS mentsofculmen length, bill depth, andtail length,and measured indi- vidual rectrices to determine tail shape.Wing lengthswere obtained INTHE EASTERN fromthe literature and from speci- mentags, although it islikely these werenot all taken by the same meth- PACIFICOCEAN' ods. Biometrics from this review will appearin PartII of thispaper. Both authors have studied Cook's Petrels IDENTIFICATIOANDoff California, and Bailey participat- ed in an April 1989 cruisethat recorded113 Cook's Petrels (Bailey et DISTRIBUTION al. 1989). Roberson observed seabirds in the eastern Pacific, August-December1989, on a NOAA- PartI ofa Two-PartSeries sponsoredsurvey. He obtainedexpe- rience with hundreds of Cook's, White-winged,and Black-winged petrels,and a few Stejneger'sand byDon Roberson and "Collared"petrels. Illustrator Keith StephenE Bailey Hansen, whose color plate will appearin PartII, alsohas experience THE SMALL PTERODROMA PETRELS and known distribution of all small withmost of thesespecies in theeast- of the subgenusCookilaria are Pterodroma in the eastern Pacific. We ern Pacific. amongthe least understood seabirds review six species:Cook's Petrel, Neither authorhas field experi- In the world. Two species,Cook's Defilippe'sPetrel, Pycroft's Petrel, encewith Defilippe'sor Pycroft's Petrel (P. cookii)and Stejneger's Stejneger'sPetrel, White-winged petrels.We discussedthese species Petrel(P. longirostris),have been Petrel(P. leucoptera, including "Col- withobservers who had field experi- recorded off the west coast of North laredPetrel" [P. (l.) brevipes]),and ence(e.g., J. A. Barde,C. Corben,B. America;others have been tentative- Black-wingedPetrel (P. -

Abstract Book

PACIFIC SEABIRD GROUP Melinda Nakagawa PaciFORTYfc-SECOND Seabird ANNUAL MEETING: Group A FUTURE FOR SEABIRDS San Jose, California, USA Annual Meeting 2015 ABSTRACT BOOK 18 - 21 February 2015 San Jose Airport Garden Hotel http://www.pacificseabirdgroup.org/ Pacific Seabird Group 42nd Annual Meeting 18-21 February 2015 San Jose, CA STANDARDIZED MONITORING OF ASHY STORM-PETREL CAPTURE–RECAPTURE RATES IN THE CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK 1Josh Adams * 1US Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center, 400 Natural Bridges Dr., Santa Cruz, CA 95060, [email protected] Channel Islands National Park (CINP) provides essential nesting habitat for greater than half the world’s population of breeding Ashy Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma homochroa). Currently, information is required to maintain, enhance, and standardize Ashy Storm-Petrel monitoring to determine trends in relative population size. Since 1975, capture-recapture efforts using mist-netting methods were conducted sporadically using varying techniques (i.e., mist-netting with and without broadcast vocalizations). No formal guidelines exist describing a standardized, repeatable approach. During 2004-07, I conducted mist-netting surveys (47 site-nights) targeting Ashy Storm-Petrels at three colony sites: Scorpion Rock off Santa Cruz Island, Santa Barbara Island, and Prince Island off San Miguel Island. I recorded 1,178 unique Ashy Storm-Petrel captures with 35 (2.9%) recaptures of previously banded storm-petrels. Power to detect 30% lesser mean standardized catch per unit effort (CPUEs) at equivalent sample size and alpha = 0.15 (85% CI), was variable across islands and years, from 39% (Prince Island 2005) to 87% (Santa Barbara Island 2005). Overall, based on, I estimated power = 96% to detect a 30% lesser CPUEs.