37</ /«.7330 MARINE DEFENSE BATTALIONS, OCTOBER 1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General John F. Kelly Commander, US Southern Command

General John F. Kelly Commander, US Southern Command General Kelly was born and raised in Boston, MA. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1970, and was discharged as a sergeant in 1972, after serving in an infantry company with the 2nd Marine Division, Camp Lejeune, NC. Following graduation from the University of Massachusetts in 1976, he was commissioned and returned to the 2nd Marine Division where he served as a rifle and weapons platoon commander, company executive officer, assistant operations officer, and infantry company commander. Sea duty in Mayport, FL, followed, at which time he served aboard aircraft carriers USS Forrestal and USS Independence. In 1980, then Captain Kelly transferred to the U.S. Army's Infantry Officer Advanced Course in Fort Benning, GA. After graduation, he was assigned to Headquarters Marine Corps, Washington, DC, serving there from 1981 through 1984, as an assignment monitor. Captain Kelly returned to the 2nd Marine Division in 1984, to command a rifle and weapons company. Promoted to the rank of Major in 1987, he served as the battalion's operations officer. In 1987, Major Kelly transferred to the Basic School, Quantico, VA, serving first as the head of the Offensive Tactics Section, Tactics Group, and later assuming the duties of the Director of the Infantry Officer Course. After three years of instructing young officers, he attended the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, and the School for Advanced Warfare, both located at Quantico. Completing duty under instruction and selected for Lieutenant Colonel, he was assigned as Commanding Officer, 1st Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion, 1st Marine Division, Camp Pendleton, CA. -

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

1945 November 26-December 2 from Red Raider to Marine Raider

1 1945 November 26-December 2 From Red Raider to Marine Raider (La Crosse Tribune, 1945 December 2, page 13) (La Crosse Tribune, 1944 March 5, page 7) Julius Wittenberg of La Crosse was a kid from a broken home who made his mark as a high school athlete and went on to become a member of one of the elite fighting units of World War II. Julius C. Wittenberg was born on May 2, 1920, in La Crosse to Frank and Sylvia (Miles) Wittenberg.1 He was named after his grandfather, Julius Wittenberg.2 Frank Wittenberg was a painter and wallpaper hanger.3 Young Julius was just four years old when Sylvia Wittenberg filed for divorce in September 1924 from her husband of 18 years. She alleged that Frank Wittenberg had "repeatedly struck her, used abusive language toward her and failed to properly support her."4 2 Four years later, Frank Wittenberg was living in Waupun, Wisconsin.5 He had taken a job as a guard at the Wisconsin state prison in Waupun. Julius, and his brother, Frank Jr., who was two years older, lived with their father at Waupun, as did a 21-year-old housekeeper named Virginia H. Ebner.6 Sylvia Wittenberg had also moved on. In October 1929, she married Arthur Hoeft in the German Lutheran parsonage in Caledonia, Minnesota.7 Arthur Hoeft of La Crosse was a veteran of World War I.8 In 1924, he had started working for his sister, Helen Mae Hoeft, at the Paramount Photo Shop at 225 Main Street. Helen Hoeft and photographer Millard Reynolds had created the first mail-order photo finishing business in the nation, and she named it Ray's Photo Service. -

World War II

World War II. – “The Blitz“ This information report describes the events of “The Blitz” during the Second World War in London. The attacks between 7th September 1940 and 10 th May 1941 are known as “The Blitz”. The report is based upon information from http://www.secondworldwar.co.uk/ , http://www.worldwar2database.com/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blitz . Prelude to the War in London The Second World War started on 1 st September 1939 with the German attack on Poland. The War in London began nearly one year later. On 24 th August 1940 the German Air Force flew an attack against Thames Haven, whereby some German bombers dropped bombs on London. At this time London was not officially a target of the German Air Force. As a return, the Royal Air Force attacked Berlin. On 5th September 1940 Hitler ordered his troops to attack London by day and by night. It was the beginning of the Second World War in London. Attack on Thames Haven in 1940 The Attacks First phase The first phase of the Second World War in London was from early September 1940 to mid November 1940. In this first phase of the Second World War Hitler achieved great military success. Hitler planned to destroy the Royal Air Force to achieve his goal of British invasion. His instruction of a sustainable bombing of London and other major cities like Birmingham and Manchester began towards the end of the Battle of Britain, which the British won. Hitler ordered the German Air Force to switch their attention from the Royal Air Force to urban centres of industrial and political significance. -

World War II-Related Exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art: Research Resources Relating to World War II World War II-Related Exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art During the war years, the National Gallery of Art presented a series of exhibitions explicitly related to the war or presenting works of art for which the museum held custody during the hostilities. Descriptions of each of the exhibitions is available in the list of past exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art. Catalogs, brochures, press releases, news reports, and photographs also may be available for examination in the Gallery Archives for some of the exhibitions. The Great Fire of London, 1940 18 December 1941-28 January 1942 American Artists’ Record of War and Defense 7 February-8 March 1942 French Government Loan 2 March 1942-1945, periodically Soldiers of Production 17 March-15 April 1942 Three Triptychs by Contemporary Artists 8-15 April 1942 Paintings, Posters, Watercolors, and Prints, Showing the Activities of the American Red Cross 2-30 May 1942 Art Exhibition by Men of the Armed Forces 5 July-2 August 1942 War Posters 17 January-18 February 1943 Belgian Government Loan 7 February 1943-January 1946 War Art 20 June-1 August 1943 Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Drawings and Watercolors from French Museums and Private Collections 8 August-5 September 1943 (second showing) Art for Bonds 12 September-10 October 1943 1DWLRQDO*DOOHU\RI$UW:DVKLQJWRQ'&*DOOHU\$UFKLYHV ::,,5HODWHG([KLELWLRQVDW1*$ Marine Watercolors and Drawings 12 September-10 October 1943 Paintings of Naval Aviation by American Artists -

During World War Ii. New Insights from the Annual Audits of German Aircraft Producers

ECONOMIC GROWTH CENTER YALE UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 208629 New Haven, CT 06520-8269 http://www.econ.yale.edu/~egcenter/ CENTER DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 905 DEMYSTIFYING THE GERMAN “ARMAMENT MIRACLE” DURING WORLD WAR II. NEW INSIGHTS FROM THE ANNUAL AUDITS OF GERMAN AIRCRAFT PRODUCERS Lutz Budraß University of Bochum Jonas Scherner University of Mannheim Jochen Streb University of Hohenheim January 2005 Notes: Center Discussion Papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussions and critical comments. The first version of this paper was written while Streb was visiting the Economic Growth Center at Yale University in fall 2004. We are grateful to the Economic Growth Center for financial support. We thank Christoph Buchheim, Mark Spoerer, Timothy Guinnane, and the participants of the Yale economic history workshop for many helpful comments. Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Jochen Streb, University of Hohenheim (570a), D- 70593 Stuttgart, Germany, E-Mail: [email protected]. This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=661102 An index to papers in the Economic Growth Center Discussion Paper Series is located at: http://www.econ.yale.edu/~egcenter/research.htm Demystifying the German “armament miracle” during World War II. New insights from the annual audits of German aircraft producers by Lutz Budraß, Jonas Scherner, and Jochen Streb Abstract Armament minister Albert Speer is usually credited with causing the boom in German armament production after 1941. This paper uses the annual audit reports of the Deutsche Revisions- und Treuhand AG for seven firms which together represented about 50 % of the German aircraft producers. -

Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past Roger Dingman University of Southern California

Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past Roger Dingman University of Southern California By any measure, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was one of the decisive events of the twentieth century. For Americans, it was the greatest military disaster in memory-one which set them on the road to becoming the world's greatest military power. For Japanese, the attack was a momentary triumph that marked the beginning of their nation's painful and protracted transition from empire to economic colossus. Thus it is entirely appropriate, more than fifty years after the Pearl Harbor attack, to pause and consider the meaning of that event. One useful way of doing so is to look back on Pearl Harbor anniversaries past. For in public life, no less than in private, anniversaries can tell us where we are; prompt reflections on where we have been; and make us think about where we may be going. Indeed, because they are occa- sions that demand decisions by government officials and media man- agers and prompt responses by ordinary citizens about the relationship between past and present, anniversaries provide valuable insights into the forces that have shaped Japanese-American relations since 1941. On the first Pearl Harbor anniversary in December 1942, Japanese and Americans looked back on the attack in very different ways. In Tokyo, Professor Kamikawa Hikomatsu, one of Japan's most distin- guished historians of international affairs, published a newspaper ar- ticle that defended the attack as a legally and morally justifiable act of self-defense. Surrounded by enemies that exerted unrelenting mili- tary and economic pressure on it, and confronted by an America that refused accommodation through negotiation, Japan had had no choice but to strike.' On Guadalcanal, where they were locked in their first protracted battle against Japanese troops, Americans mounted a "hate shoot" against them to memorialize those who had died at Pearl Har- bor a year earlier.2 In Honolulu, the Advertiser editorial writer urged The ]journal of American-East Asian Relations, Vol. -

Washington, Thursday, January 15, 1942

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 7 f\ i » 9 3 4 ^ NUMBER 10 c O a/ i t ì O ^ Washington, Thursday, January 15, 1942 The President shall be held for subsequent credit upon CONTENTS indebtedness to the Corporation, in ac cordance with the provisions of THE PRESIDENT EXECUTIVE ORDER §§ 12.3112-51 and 12.3112-52.* Executive Order: Pa6e *§§ 12.3112-50 to 12.3112-52, inclusive, Alaska, partial revocation of or Partial R evocation of Executive Order issued under the authority contained in 48 der withdrawing certain No. 6957 of F ebruary 4, 1935, W it h Stat. 344, 845; 12 U.S.C. §§ 1020, 1020a. public lands-------------------- 267 drawing Certain P ublic Lands § 12.3112-51 ' Interest; application of RULES, REGULATIONS, ALASKA conditional payments on indebtedness; ORDERS By virtue of the authority vested in disposition of unapplied conditional pay me by the act of June 25, 1910, c. 421, ments after payment of indebtedness in T itle 6—Agricultural Credit: 36 Stat. 847, Executive Order No. 6957 full. The provisions of §§ 10.387-51, Farm Credit Administration: of February 4, 1935, temporarily with 10.387-52, and 10.387-53,1 Part 10 of Title Federal Farm Mortgage Cor drawing certain lands in Alaska from ap 6, Code of Federal Regulations, dealing poration, conditional pay propriation under the public-land laws, with “Interest”, “Application of condi ments by borrowers------ 267 is hereby revoked as to the following- tional payments on indebtedness”, and Loans by production credit described tracts, in order to validate “Disposition of unapplied conditional associations, charges to homestead entry No. -

The Demarcation Line

No.7 “Remembrance and Citizenship” series THE DEMARCATION LINE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE General Secretariat for Administration DIRECTORATE OF MEMORY, HERITAGE AND ARCHIVES Musée de la Résistance Nationale - Champigny The demarcation line in Chalon. The line was marked out in a variety of ways, from sentry boxes… In compliance with the terms of the Franco-German Armistice Convention signed in Rethondes on 22 June 1940, Metropolitan France was divided up on 25 June to create two main zones on either side of an arbitrary abstract line that cut across départements, municipalities, fields and woods. The line was to undergo various modifications over time, dictated by the occupying power’s whims and requirements. Starting from the Spanish border near the municipality of Arnéguy in the département of Basses-Pyrénées (present-day Pyrénées-Atlantiques), the demarcation line continued via Mont-de-Marsan, Libourne, Confolens and Loches, making its way to the north of the département of Indre before turning east and crossing Vierzon, Saint-Amand- Montrond, Moulins, Charolles and Dole to end at the Swiss border near the municipality of Gex. The division created a German-occupied northern zone covering just over half the territory and a free zone to the south, commonly referred to as “zone nono” (for “non- occupied”), with Vichy as its “capital”. The Germans kept the entire Atlantic coast for themselves along with the main industrial regions. In addition, by enacting a whole series of measures designed to restrict movement of people, goods and postal traffic between the two zones, they provided themselves with a means of pressure they could exert at will. -

British Responses to the Holocaust

Centre for Holocaust Education British responses to the Insert graphic here use this to Holocaust scale /size your chosen image. Delete after using. Resources RESOURCES 1: A3 COLOUR CARDS, SINGLE-SIDED SOURCE A: March 1939 © The Wiener Library Wiener The © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. Where was the photograph taken? Which country? 2. Who are the people in the photograph? What is their relationship to each other? 3. What is happening in the photograph? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the image. SOURCE B: September 1939 ‘We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people.’ © BBC Archives BBC © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph and the extract from the document. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. The person speaking is British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. What is he saying, and why is he saying it at this time? 2. Does this support the belief that Britain declared war on Germany to save Jews from the Holocaust, or does it suggest other war aims? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the sources. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

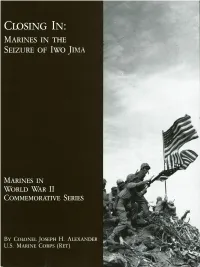

Closingin.Pdf

4: . —: : b Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima by Colonel Joseph H. Alexander, USMC (Ret) unday, 4 March 1945,sion had finally captured Hill 382,infiltrators. The Sunday morning at- marked the end of theending its long exposure in "The Am-tacks lacked coordination, reflecting second week ofthe phitheater;' but combat efficiencythe division's collective exhaustion. U.S. invasion of Iwohad fallen to 50 percent. It wouldMost rifle companies were at half- Jima. By thispointdrop another five points by nightfall. strength. The net gain for the day, the the assault elements of the 3d, 4th,On this day the 24th Marines, sup-division reported, was "practically and 5th Marine Divisions were ex-ported by flame tanks, advanced anil." hausted,their combat efficiencytotalof 100 yards,pausingto But the battle was beginning to reduced to dangerously low levels.detonate more than a ton of explo-take its toll on the Japanese garrison The thrilling sight of the Americansives against enemy cave positions inaswell.GeneralTadamichi flag being raised by the 28th Marinesthat sector. The 23d and 25th Ma-Kuribayashi knew his 109th Division on Mount Suribachi had occurred 10rines entered the most difficult ter-had inflicted heavy casualties on the days earlier, a lifetime on "Sulphurrain yet encountered, broken groundattacking Marines, yet his own loss- Island." The landing forces of the Vthat limited visibility to only a fewes had been comparable.The Ameri- Amphibious Corps (VAC) had al-feet. can capture of the key hills in the ready sustained 13,000 casualties, in- Along the western flank, the 5thmain defense sector the day before cluding 3,000 dead.