Gigantomachy, Callimachean Poetics, and Literary Filiation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

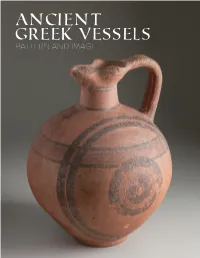

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

2000 Texas State Certamen -- Round One, Upper Level Tu

2000 TEXAS STATE CERTAMEN -- ROUND ONE, UPPER LEVEL TU #1: What girl, abandoned on Naxos, became the bride of Dionysus? ARIADNE B1: Who had abandoned Ariadne, after she had helped to save his life? THESEUS B2: What sister of Ariadne later married Theseus? PHAEDRA TU#2: Who wrote the Epicurean work De Rerum Natura? LUCRETIUS B1: Of what did Lucretius reputedly die? LOVE POTION B2: What famous Roman prepared De Rerum Natura for publishing after the death of Lucretius? CICERO TU #3: Who was turned into a weasel for tricking Eileithyia into allowing Heracles to be born? GALANTHIS B1: Who was the half-brother of Heracles, and the son of Amphitryon? IPHICLES B2: Who was the nephew of Heracles who helped him to kill the Hydra? IOLAUS TU#4: Whose co-consul was Caesar in 59 B.C.? (CALPURNIUS) BIBULUS B1&2: For five points each, name two of the three provinces Caesar oversaw during his first consulship. ILLYRICUM, GALLIA CISALPINA, GALLIA NARBONENSIS/TRANSALPINA (aka PROVINCIA) TU #5: What type of verb are soleÇ, gaudeÇ, and f§dÇ? SEMI-DEPONENT B1: Say ‘I used to rejoice’ in Latin. GAUDEBAM B2; Say ‘I have rejoiced’ in Latin. GAV¦SUS/-A SUM TU#6: Although they were called the Aloadae, Otus and Ephialtes were really the sons of which god? POSEIDON B1: How did the mother of the Aloadae attract Poseidon? STOOD IN THE SEA AND SPLASHED WATER ON HERSELF UNTIL HE IMPREGNATED HER B2: What deity tricked Otus and Ephialtes into killing each other? ARTEMIS TU #7: What was the dinner held on the ninth day after a death called? CENA NOVENDIALIS B1: What was the minimum burial for religious purposes? THREE HANDFULS OF DIRT B2: What was a cenotaphium? A TOMB ERECTED IF THE BODY COULD NOT BE RECOVERED (AN EMPTY TOMB) TU#8: Who called his work nugae? CATULLUS B1: To what fellow author did he dedicate them? CORNELIUS NEPOS B2: Catullus was most famous for his love poetry to what lady? LESBIA/CLODIA TU #9: Romulus and Remus were brothers, but what is the meaning of the Latin word remus? OAR B1: With this in mind, what is a remex? ROWER/OARSMAN B2: Define remigÇ. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Tammuz Pan and Christ Otes on a Typical Case of Myth-Transference

TA MMU! PA N A N D C H R IST O TE S O N A T! PIC AL C AS E O F M! TH - TR ANS FE R E NC E AND DE VE L O PME NT B! WILFR E D H SC HO FF . TO G E THE R WIT H A BR IE F IL L USTR ATE D A R TIC L E O N “ PA N T H E R U STIC ” B! PAU L C AR US “ " ' u n wr a p n on m s on u cou n r , s n p r n u n n , 191 2 CHIC AGO THE O PE N CO URT PUBLISHING CO MPAN! 19 12 THE FA N F PRAXIT L U O E ES. a n t Fr ticpiccc o The O pen C ourt. TH E O PE N C O U RT A MO N TH L! MA GA! IN E Devoted to th e Sci en ce of Religion. th e Relig ion of Science. and t he Exten si on of th e Religi on Periiu nen t Idea . M R 1 12 . V XX . P 6 6 O L. VI o S T B ( N . E E E , 9 NO 7 Cepyricht by The O pen Court Publishing Gumm y, TA MM ! A A D HRI T U , P N N C S . NO TES O N A T! PIC AL C ASE O F M! TH-TRANSFERENC E AND L DEVE O PMENT. W D H H FF. -

Between Arcadia and Crete: Callisto in Callimachus' Hymn to Zeus The

Between Arcadia and Crete: Callisto in Callimachus’ Hymn to Zeus The speaker of Callimachus’ Hymn to Zeus famously asks Zeus himself whether he should celebrate the god as “Dictaean,” i.e. born on Mt. Dicte in Crete, or “Lycaean,” born on Arcadian Mt. Lycaeus (4-7). When the response comes, “Κρῆτες ἀεὶ ψεῦσται” (“Cretans are always liars,” 8), the hymnist agrees, and for support recalls that the Cretans built a tomb for Zeus, who is immortal (8-9). In so dismissing Cretan claims to truth, the hymnist justifies an Arcadian setting for his ensuing birth narrative (10-41). Curiously, however, after recounting Zeus’s birth and bath, the hymnist suddenly locates the remainder of the god’s early life in Crete after all (42-54). The transition is surprising, not only because it runs counter to the previous rejection of Cretan claims, but also because the Arcadians themselves held that Zeus was both born and raised in Arcadia (Paus. 8.38.2). While scholars have focused on how the ambiguity of two place names (κευθμὸν... Κρηταῖον, 34; Θενάς/Θεναί, 42, 43) misleads the audience and/or prepares them for the abrupt move from Arcadia to Crete (Griffiths 1970 32-33; Arnott 1976 13-18; McLennan 1977 66, 74- 75; Tandy 1979 105, 115-118; Hopkinson 1988 126-127), this paper proposes that the final word of the birth narrative, ἄρκτοιο (“bear,” 41), plays an important role in the transition as well. This reference to Callisto a) allusively justifies the departure from Arcadia, by suggesting that the Arcadians are liars not unlike the Cretans; b) prepares for the hymnist’s rejection of the Cretan account of Helice; and c) initiates a series of heavenly ascents that binds the Arcadian and Cretan portions of the hymn and culminates climactically with Zeus’s own accession to the sky. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed. -

Wjcl Certamen 2016 Advanced Division Round One

WJCL CERTAMEN 2016 ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Brontes, Steropes, and Arges were the name of these beings that helped Hephaestus in his forge under Mt. Etna. What is the name typically given to these three? CYCLOPES B1. Cottus, Briareus, and Gyges are the names of what beings with fifty heads and one hundred hands? HECATONCHEIRES B2. The Cyclopes and Hecatoncheires were siblings. Name their parents. URANUS AND GAIA 2. From what Latin verb with what meaning is the English word “tactile” derived? TANGŌ, TANGERE MEANING TO TOUCH B1. From what Latin verb with what meaning is the English word “nuptial” derived? NŪBŌ, NŪBERE MEANING TO MARRY/VEIL B2. From what Latin verb with what meaning is the English word “pensive” derived? PENDŌ, PENDERE MEANING TO HANG/WEIGH 3. Which governor of Syria declared himself emperor upon hearing a rumor that Marcus Aurelius had died and continued his revolt even after learning that Marcus Aurelius was alive? AVIDIUS CASSIUS B1. Which governor of Germania Superior led a rebellion against the emperor Domitian in 89 CE but failed due to a sudden thaw of the Rhine that prevented his allies from joining him? LUCIUS ANTONIUS SATURNINUS B2. Which governor of Syria declared himself emperor when Pertinax died and was defeated in battle, then killed while fleeing to Parthia? PESCENNIUS NIGER 4. What Latin word most nearly means “a groan”? GEMITUS, GEMITŪS B1. What Latin word most nearly means “reputation”? FĀMA, FAMAE B2. What Latin word most nearly means “fleet”? CLASSIS, CLASSIS 5. What author describes the plague of Athens in a didactic work edited by Cicero entitled De Rerum Natura? LUCRETIUS B1. -

Myth and Reality in the Battle Between the Pygmies and the Cranes in the Greek and Roman Worlds

ARTÍCULOS Gerión. Revista de historia Antigua ISSN: 0213-0181 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/GERI.56960 Myth and Reality in the Battle between the Pygmies and the Cranes in the Greek and Roman Worlds Asher Ovadiah1; Sonia Mucznik2 Recibido: 19 de septiembre de 2016 / Aceptado: 23 de marzo de 2017 Abstract. Ancient writers, such as Homer, Aesop, Hecataeus of Miletus, Herodotus, Aristotle, Philostratus, Pliny the Elder, Juvenal and others have often referred to the enmity and struggle between the Pygmies and the Cranes. It seems that this folk-tale was conveyed to the Greeks through Egyptian sources. Greek and Roman visual works of art depict the Pygmies fighting against the vigorous and violent attack of the birds, which in some cases was vicious. This article sets out to examine the reasons for the literary and artistic portrayals of the Battle between the Pygmies and the Cranes (Geranomachy) in the context of the migration of the cranes in the autumn from the Caucasus (Scythian plains) to Central (Equatorial) Africa. In addition, an attempt will be made to clarify whether the literary sources and visual works of art reflect myth and/or reality. Keywords: Egypt; Ethiopia; Geranomachy; Migration; Nile; Scythia; Trojans. [en] Mito y realidad en la batalla entre los pigmeos y las grullas en el mundo griego y romano Resumen. Escritores antiguos, tales como Homero, Esopo, Hecateo de Mileto, Herodoto, Aristóteles, Filóstrato, Plinio el Viejo, Juvenal y otros se refirieron frecuentemente a la enemistad y guerra entre los pigmeos y las grullas. Es posible que este cuento popular fuese transmitido a los griegos a través de fuentes egipcias. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

THE FINAL LINE in CALLIMACHUS' HYMN to APOLLO Giuseppe Gian Grande

http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Habis.1992.i23.05 THE FINAL LINE IN CALLIMACHUS' HYMN TO APOLLO Giuseppe Gian grande King' s College, London Un examen del verso final del Himno a Apolo de Calímaco dentro del marco de las teorías poéticas calimaqueas lleva a la conclusión de que la lectura OBóvos- es genuina, mientras que la variante .950ópoç es una trivialización. An analysis of the final une of Callimachus Hymn to Apollo, conducted within the framework of the poet' s literary theories, shows that the reading 006- voç is genuine, whereas the variant 006pos- is a trivialization. The final une in Callimachus' Hymn to Apollo has been the subject of copious debate during the last centuries. Fortunately for us, most of the relevant material has been assembled by F. Williams, in his doctoral dissertation which was directed by me at my Classics Research Centre, University of London, so that I can now conveniently refer the readers to the monograph in question 1 • As is well known, the problem consists in choosing between the variants 00óvos- or 00ópoç in fine 113. The editiones veteres, as Ernesti noted in his commentary ad loc. 2, read xaí'pe cYval'. 6 8é- .1114.1os-, 1'v '6 00óvos-, gvOci ué-otTO 1 F. Williams, Callimachus' Hymn to Apollo (Oxford 1978) 96 ff. 2 Jo. Aug. Emesti, Callimachi Hymni, Epigrammata el Fragmenta I (Lugduni Batavorum 1761) 65. 53 HABIS 23 (1992) 53-62 THE FINAL LINE IN CALLIMACHUS' HYMN TO APOLLO but the variant ~vos- was rejected by Emesti, who judged 00ópos- to be the cor- rect one. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience.