Pastoralists in a Colonial World1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gazetteers Organisation Revenue Department Haryana Chandigarh (India) 1998

HARYANA DISTRICT GAZETTEEERS ------------------------ REPRINT OF AMBALA DISTRICT GAZETTEER, 1923-24 GAZETTEERS ORGANISATION REVENUE DEPARTMENT HARYANA CHANDIGARH (INDIA) 1998 The Gazetteer was published in 1925 during British regime. 1st Reprint: December, 1998 © GOVERNMENT OF HARYANA Price Rs. Available from: The Controller, Printing and Stationery, Haryana, Chandigarh (India). Printed By : Controller of Printing and Stationery, Government of Haryana, Chandigarh. PREFACE TO REPRINTED EDITION The District Gazetteer is a miniature encyclopaedia and a good guide. It describes all important aspects and features of the district; historical, physical, social, economic and cultural. Officials and other persons desirous of acquainting themselves with the salient features of the district would find a study of the Gazetteer rewarding. It is of immense use for research scholars. The old gazetteers of the State published in the British regime contained very valuable information, which was not wholly reproduced in the revised volume. These gazetteers have gone out of stock and are not easily available. There is a demand for these volumes by research scholars and educationists. As such, the scheme of reprinting of old gazetteers was taken on the initiative of the Hon'ble Chief Minister of Haryana. The Ambala District Gazetteer of 1923-24 was compiled and published under the authority of Punjab Govt. The author mainly based its drafting on the assessment and final reports of the Settlement Officers. The Volume is the reprinted edition of the Ambala District Gazetteer of 1923-24. This is the ninth in the series of reprinted gazetteers of Haryana. Every care has been taken in maintaining the complete originality of the old gazetteer while reprinting. -

Unclaimed Dividend Amount As on AGM 10Th August 2017.Xlsx

CIN/ BCIN L63010GJ1992PLC018106Company/Bank Name GUJARAT PIPAVAV PORT LIMITED Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 10-Aug-17 Prefill Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 638130.20 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sale proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of transfer to Investor First Name Investor Middle Name Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/ Husband Middle Name Father/ Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio No. DP ID- Client ID Investment Type Amount transferred IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) ACHALABEN A PATEL NA AT & PO ANKLAV (MOUKHADKI ) TA BORSAD DIST KAIRA INDIA GUJARAT BORSAD 388540PA0008729 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 4750.0017-SEP-2023 RADHABEN SUBHASH SARDA NA C/O. SARDA & CO., CENTRAL BANK ROAD, JAMNAGAR. INDIA GUJARAT JAMNAGAR 361001 IN300974-IN300974-10178506 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 3800.00 17-SEP-2023 HITEN PATEL NA 2-F,SURYARATH, PANCHWATI, AHMEDABAD INDIA GUJARAT AHMEDABAD 380006PH0007765 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 4750.0017-SEP-2023 PATEL HETAL HIRENBHAI PATEL HIRENBHAI BALDEVBHAI 239, KARSANDAS MADH, NARDIPUR, KALOL, GANDHINAGAR. INDIA GUJARAT GANDHI NAGAR 382735 IN300343-IN300343-10841739 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend 2280.0017-SEP-2023 YOGIRAJ G PATEL NA 7 ARYA NAGAR -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Yamunanagar, Part XII A

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CEN.SUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE &TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR Direqtor of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana. 1995 ir=~~~==~==~==~====~==~====~~~l HARYANA DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR t, :~ Km 5E3:::a::E0i:::=::::i====310==::::1i:5==~20. Km C.O.BLOCKS A SADAURA B BILASPUR C RADAUR o JAGADHRI E CHHACHHRAULI C.D.BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUTORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1.1.1990 W. R.C. WORKSHOP RAILWAY COLONY DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR CHANGE IN JURI50lC TION 1981-91 KmlO 0 10 Km L__.j___l BOUNDARY, STATE ... .. .. .. _ _ _ DISTRICT _ TAHSIL C D. BLOCK·:' .. HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT; TAHSIL; e.D. BLOCK @:©:O STATE HIGHWAY.... SH6 IMPORT ANi MEiALLED ROAD RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION. BROAD GAUGE RS RIVER AND STREAMI CANAL ~/--- - Khaj,wan VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME - URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE-CLASS I,II,IV &V .. POST AND TElEGRAPH OFFICE. PTO DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION ... ••••1Bl m BOUNDARY, STATE DISTRICT REST HOUSE, TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW, FOREST BUNGALOW RH TB rB CB TA.HSIL AND CANAL BUNGALOW NEWLY CREATED DISTRICT YAMuNANAGAR Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/FB/CB, ~tc. are shown as .. .Damla HAS BEEN FORMED BY TRANSFERRING PTO AREA FROM :- Western Yamuna Canal W.Y.C. olsTRle T AMBAl,A I DISTRICT KURUKSHETRA SaSN upon Survt'y of India map with tn. p.rmission of theo Survt'yor Gf'nf'(al of India CENSUS OF INDIA - 1991 A - CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS The publications relating to Haryana bear series No. -

Beyond 'Tribal Breakout': Afghans in the History of Empire, Ca. 1747–1818

Beyond 'Tribal Breakout': Afghans in the History of Empire, ca. 1747–1818 Jagjeet Lally Journal of World History, Volume 29, Number 3, September 2018, pp. 369-397 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2018.0035 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719505 Access provided at 21 Jun 2019 10:40 GMT from University College London (UCL) Beyond ‘Tribal Breakout’: Afghans in the History of Empire, ca. 1747–1818 JAGJEET LALLY University College London N the desiccated and mountainous borderlands between Iran and India, Ithe uprising of the Hotaki (Ghilzai) tribes against Safavid rule in Qandahar in 1717 set in motion a chain reaction that had profound consequences for life across western, south, and even east Asia. Having toppled and terminated de facto Safavid rule in 1722,Hotakiruleatthe centre itself collapsed in 1729.1 Nadir Shah of the Afshar tribe—which was formerly incorporated within the Safavid political coalition—then seized the reigns of the state, subduing the last vestiges of Hotaki power at the frontier in 1738, playing the latter off against their major regional opponents, the Abdali tribes. From Kandahar, Nadir Shah and his new allies marched into Mughal India, ransacking its cities and their coffers in 1739, carrying treasure—including the peacock throne and the Koh-i- Noor diamond—worth tens of millions of rupees, and claiming de jure sovereignty over the swathe of territory from Iran to the Mughal domains. Following the execution of Nadir Shah in 1747, his former cavalry commander, Ahmad Shah Abdali, rapidly established his independent political authority.2 Adopting the sobriquet Durr-i-Durran (Pearl of 1 Rudi Matthee, Persia in Crisis. -

On the Brink: Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana By

Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana August 2010 For copies and further information, please contact: PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar, Phase I, Delhi – 110 091, India Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development PEACE Institute Charitable Trust P : 91-11-22719005; E : [email protected]; W: www.peaceinst.org Published by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar – I, Delhi – 110 091, INDIA Telefax: 91-11-22719005 Email: [email protected] Web: www.peaceinst.org First Edition, August 2010 © PEACE Institute Charitable Trust Funded by Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) under a Sir Dorabji Tata Trust supported Water Governance Project 14-A, Vishnu Digambar Marg, New Delhi – 110 002, INDIA Phone: 91-11-23236440 Email: [email protected] Web: www.watergovernanceindia.org Designed & Printed by: Kriti Communications Disclaimer PEACE Institute Charitable Trust and Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in this report. All rights reserved. Information contained in this report may be used freely with due acknowledgement. When I am, U r fine. When I am not, U panic ! When I get frail and sick, U care not ? (I – water) – Manoj Misra This publication is a joint effort of: Amita Bhaduri, Bhim, Hardeep Singh, Manoj Misra, Pushp Jain, Prem Prakash Bhardwaj & All participants at the workshop on ‘Water Governance in Yamuna Basin’ held at Panipat (Haryana) on 26 July 2010 On the Brink... Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana i Acknowledgement The roots of this study lie in our research and advocacy work for the river Yamuna under a civil society campaign called ‘Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan’ which has been an ongoing process for the last three and a half years. -

05 Mar 2018 174510950BSUT

INDEX S. NO. CONTENTS PAGENO. 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION OF THE PROJECT/BACKGROUND INFORMATION 5 3.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 7 4.0 SITE ANALYSIS 29 5.0 PLANNING BRIEF 31 6.0 PROPOSED INFRASTRUCTURE 32 7.0 REHABILITATION AND RESETTLEMENT (R & R) PLAN 33 8.0 PROJECT SCHEDULE & COST ESTIMATES 33 9.0 ANALYSIS OF PROPOSAL 33 i Expansion of Distillery (165 KLPD to 300 KLPD) & Co-Generation Power Plant (7.0 to 15.0 MW) by installation of Unit II 135 KLPD Grain / Molasses Based Distillery & 8.0 MW Co-Generation Power Plant within Existing Plant Premises At Village Jundla, Tehsil Karnal, District Karnal, Haryana Pre - Feasibility Report PRE - FEASIBILITY REPORT 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (I) Introduction Haryana Liquors Pvt. Ltd. is one of the leading manufacturers in the Alcohol industry in North India and is part of the CDB Group. Established in the year 2015, Haryana Liquors Pvt. Ltd. is engaged in manufacturing, marketing and sale of Country Liquor, Indian Made Foreign Liquor (IMFL), Bulk Alcohol and contract bottling for established IMFL brands. The Company has a well-established presence in the Country Liquor segment and is making its mark in the IMFL segment by doing contract bottling to cater to renowned Indian players. CDB Group currently operates three modern and fully integrated Distilleries at Banur & Khasa Punjab and Jundla, Haryana. It has one of the largest and most efficient grain based distilleries in India with highest alcohol recovery per unit of grain. Haryana Liquors Pvt. Ltd. is presently operating 165 KLPD Grain based Distillery along with 7.0 MW Co-generation Power Plant at Village Jundla, Tehsil Karnal, District Karnal, Haryana. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

1 TRIBE and STATE in WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis

1 TRIBE AND STATE IN WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for PhD degree at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673067 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673067 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis begins by describing the socio-political and economic organisation of the tribes of Waziristan in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as aspects of their culture, attention being drawn to their egalitarian ethos and the importance of tarburwali, rivalry between patrilateral parallel cousins. It goes on to examine relations between the tribes and the British authorities in the first thirty years after the annexation of the Punjab. Along the south Waziristan border, Mahsud raiding was increasingly regarded as a problem, and the ways in which the British tried to deal with this are explored; in the 1870s indirect subsidies, and the imposition of ‘tribal responsibility’ are seen to have improved the position, but divisions within the tribe and the tensions created by the Second Anglo- Afghan War led to a tribal army burning Tank in 1879. -

Village List of Gujranwala , Pakistan

Census 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-18 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST I PUNJAB Lahore Divisiona .,.(...t..G.ElCY- OF THE PROVINCIAL TEN DENT CENSUS, JUr.8 1952 ,NO BAHAY'(ALPUR Prleo Ps. 6·8-0 FOREWORD This Village List has been pr,epared from the material collected in con" nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be avaflable and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showing its area to the nearest square mile. and Its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsil the Revenue Kanungo holqos are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo holqa and the remaining Villages comprising the ha/qas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column o. Rokhs (tree plantations) and other similar areas even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast numbers have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries. -

S.No. Date 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. III YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2019-20 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. DATE NAME ASEEM AARUSH SHANKER 1 SRIVASTAV SRIVASTAV A A IRSHAD ABDUL 2 HUSSAIN HADI MANSOORI ABDUL ABDUL 3 MANNAN JABBAR ABDUL MOHAMM 4 REHAN ED RAFIQ ABHAY BHERU LAL 5 KABRA KABRA CHANDRA ABHAY PRAKASH 6 KHOKHAW KHOKHAW AT AT ABHISHEK JAGDISH 7 MENARIYA CHANDRA ABHISHEK DINESH 8 NAGDA NAGDA BHOPAL ADITI SINGH 9 CHUNDAW CHUNDAW AT AT ADITI AJAY SINGH 10 CHUNDAW CHUNDAW AT AT BHANWAR AJAY 11 LAL KHARADI KHARADI AJAY KAMAL 12 PRAJAPAT PRAJAPAT AKASH KISHAN 13 DAHIMA DAHIMA AKASH ARJUN LAL 14 SUTHAR SUTHAR AKSHIKA 15 ABHAY JAIN JAIN AKSHITA BHUPENDR 16 SONI A SONI ALI ASGAR 17 KEZAR ALI SALUMBER SAJID ALI ASGAR HUSSAIN 18 TIREE TIREE WALA WALA AMAR NAND LAL 19 CHANDRA TELI TELI TIKAM ANAMIKA 20 SINGH RAJPUT RAJPUT DILIP ANITA 21 SINGH PARMAR PARMAR 22 ANJALI VED LALA VED ANKITA BHUPENDR 23 JAIN A JAIN KANHAIYA ANMOL 24 LAL MENARIA MENARIA ARIHANT Fateh Lal 25 DANI Dani ARPAN Chanchal 26 BHATNAGA Bhatnagar R ARUN ROSHAN 27 MOCHI LAL MOCHI PADMARA ASHA M 28 CHOUDHAR CHOUDHAR Y Y ASHA HIMMAT 29 KUNWAR SINGH CHUNDAW CHUNDAW AT AT MAHAVEER ASHISH KUMAR 30 GANGAWA GANGAWA T T ASHUTOSH MOHAN 31 DEORA LAL DEORA RAJENDRA ASHUTOSH 32 KUMAR SOMANI SOMANI ASHWINI CHAMPA 33 JAIN LAL JAIN BHAGWAN GULAB 34 SINGH SINGH SHAKTAWA SHAKTAWA T T BHARAT GEHARI LAL 35 KUMAWAT KUMAWAT BHARAT SUKH LAL 36 SAHU SAHU BHARAT ROD SINGH 37 SINGH RAO RAO BHAVANA BASANTI 38 BAMBORIY LAL A BHAVANA BANSHI LAL 39 SUTHAR -

Project Report Template

MAHINDRA - TERI CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR SUSTAINABLE HABITATS Water Sustainability Assessment Of Gurugram City Water Sustainability Assessment of Gurugram City © The Energy and Resources Institute 2021 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2021 Water Sustainability Assessment of Gurugram City New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. 82 pp. THE TEAM Technical Team Mr Akash Deep, Senior Manager, GRIHA Council Ms Tarishi Kaushik, Research Associate, TERI Support Team Mr Dharmender Kumar, Administrative Officer, TERI Technical Reviewer Prof. Arun Kansal, Dean (Research and Relationships), TERI School of Advanced Studies, New Delhi For more information Project Monitoring Cell T E R I Tel. 2468 2100 or 2468 2111 Darbari Seth Block E-mail [email protected] IHC Complex, Lodhi Road Fax 2468 2144 or 2468 2145 New Delhi – 110 003 Web www.teriin.org India India +91 • Delhi (0)11 Preface Literature describes urban areas as open systems with porous boundaries and highlights the importance of a systems perspective for understanding ecological sustainability of human settlement. Similarly, a socio-ecological framework helps us to understand the nexus between social equity, environmental sustainability, and economic efficiency. India is urbanizing rapidly with characteristic inequality and conflicts across the social, economic, and locational axes. Following the global pattern, Indian cities use social and natural resources of the rural hinterland and their own resources for survival and growth and, in the process, generate large amount of waste. Water is the most important ‘resource flow’ in an urban area, driven by a complex set of intersecting socio-economic, political, infrastructural, hydrological, and other factors. These drivers vary a great deal within a city and has a significant impact on the water flow and management and requires both micro and macro level study in order to address it. -

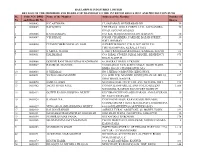

SL No. Folio NO./ DPID and Client ID No. Name of the Member Address of the Member Number of Shares 1 0000002 H C ASTHANA 17

BALLARPUR INDUSTRIES LIMITED DETAILS OF THE MEMBERS AND SHARE FOR TRANSFER TO THE INVESTOR EDUCATION AND PROTECTION FUND SL Folio NO./ DPID Name of the Member Address of the Member Number of No. and Client ID No. Shares 1 0000002 H C ASTHANA 17, SAIFABAD, HYDERABAD-DN. 30 2 0000003 RAFIQ BEG THE PRAGA TOOLS CORPN. LTD., ALEXANDRA 30 ROAD, SECUNDARABAD. 3 0000006 K M HAMEEDA C/O. K.B. MAQSOOD HUSSAIN, BADAUN, 30 4 0000007 V K DHAGE PODAR CHAMBERS, PARESEE BAZAR STREET, 30 FORT, BOMBAY 5 0000020 PUTHENCHERI GOPALAN NAIR SUPERINTENDENT, P.W.D. M.P. RETD P.O. 75 TIRUVEGAPPURA, KERALA STATE 6 0000029 S ABDUL WAHIB 5, OLD TRANQUEBAR STREET, KARIKAL, SOUTH 63 7 0000051 HALIMABAI C/O. IQBAL STORES, IQBAL MANZIL, RESIDENCY 975 ROAD, NAGPUR. 8 0000066 GOBIND RAM THAKURDAS WADHWANI 48, HAZRAT GANJ LUCKNOW. 3 9 0000067 RAMBHAU BANGDE C/O BHARATI SAW & RICE MILLS, EKORI WARD, 72 BINBA ROAD, CHANDRAPUR, M.S. 10 0000083 S J KHARAS NO.5,JEERA COMPOUND, KINGSWAY, 9 11 0000091 VATSALABAI MANDPE C/O. SHRI D.W. MANDPE, HINDUSTHAN OIL MILLS, 657 GHAT ROAD, NAGPUR. 12 0000098 SAMUEL JOHN NETURIA COAL CO./P/ LTD., P.O. NETURIA, DIST. 192 13 0000102 JAGJIT SINGH PAUL C/O.M/S. BANWARILAL AND CO LTD QUEENS 1,566 MANSIONS, BASTION ROAD FORT BOMBAY 14 0000122 GOTETI RADHA KRISHNA MURTY KUCHMANCHIVANI AGRAHARAM, AMALAPURAM, 30 DT. EAST GODAVARI. 15 0000124 K ANASUYA C/O P PATHU RAJU KEAVEKALKURGUMME 3 GUDDE,CIRCAR THOTA MACHLIPATTAM,KRISHNA 16 0000127 VENGARA RADHAKRISHNA MURTY 4-61/10 DILSHUKHNAGAR HYDERABAD 78 17 0000129 BALWANT SINGH AGRICULTURAL ASSISTANT, 85, MODEL TOWN, 192 18 0000131 GANGABAI MAHADEORAO JOGLEKAR JOGLEKAR WADA, GANJIPURA, JABALPUR.