Municipal & Planning Law Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2008

2008 Special thanks to our volunteer photographers: Alan Dunlop (including cover), Catherine Guillame Chow, Dario Sante and Julian Sale. DAREarts EMPOWERING AT RISK CHILDREN DAREarts is arts education that empowers ‘at risk’ children. This is the best day of my life. DAREarts child, 9 DAREarts dares children to make positive choices in their lives through educational experiences in art, architecture, dance, drama, design, fashion, literature, music, – all the arts. You are saving this child from the wrong crowd. Principal DAREarts is a national, not-for-profit organization which stands for Discipline, Action and Responsibility in Education. DAREarts’ 5-year all-the-arts program empowers ‘at risk’ 9–14 year olds who have been chosen from elementary schools in less advantaged areas to become leaders. The children paint, sculpt, sing, dance, compose, design, write, act and create as they ‘travel’ through the centuries exploring world cultures, guided by arts professionals. The children gain self esteem and leadership skills and then return to their schools to teach their classmates. Since 1996, DAREarts has flourished in Ontario and is expanding across Canada, influencing over 10,000 children yearly. For more information, visit www.darearts.com DAREarts Foundation Inc. 3042 Concession 3 Adjala, RR 1, Palgrave, Ontario, Canada L0N 1P0 • 1-888-540-2787 / 905-729-0097 Canadian CharitaBle Registration NUMBer 88691 7764 RR0002 DareArts’ Aboriginal Youth Program: DareArts From past participation in the Canadian Armed Force’s Junior Letter to Rangers camps, DareArts’ artists-as-teachers worked in the remote northern aboriginal community of Webequie to help to combat teen suicide and inspire the youth while building Members their self-esteem. -

Novae Res Urbis

FRIDAY, JUNE 16, 2017 REFUSAL 3 20 YEARS LATER 4 Replacing rentals Vol. 21 Stronger not enough No. 24 t o g e t h e r 20TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION NRU TURNS 20! AND THE STORY CONTINUES… Dominik Matusik xactly 20 years ago today, are on our walk selling the NRU faxed out its first City neighbourhood. But not the E of Toronto edition. For the developers. The question is next two decades, it covered whether the developers will the ups and downs of the city’s join the walk.” planning, development, and From 2017, it seems like municipal affairs news, though the answer to that question is a email has since replaced the fax resounding yes. machine. Many of the issues “One of the innovative the city cared about in 1997 still parts of the Regent Park resonate in 2017. From ideas for Revitalization,” downtown the new Yonge-Dundas Square city planning manager David to development charges along Oikawa wrote in an email the city’s latest subway line and to NRU, “was the concept of trepidations about revitalizing using [condos] to fund the Regent Park. It was an eventful needed new assisted public year. housing. A big unknown at The entire first edition of Novæ Res Urbis (2 pages), June 16, 1997 Below are some headlines from the time was [whether] that NRU’s first year and why these concept [would] work. Would issues continue to captivate us. private home owners respond to the idea of living and New Life for Regent Park investing in a mixed, integrated (July 7, 1997) community? Recently, some condo townhouses went on sale In 1997, NRU mused about the in Regent Park and were sold future of Regent Park. -

Minutes of the Council of the City of Toronto 1 October 1, 2 and 3, 2002

Minutes of the Council of the City of Toronto 1 October 1, 2 and 3, 2002 Guide to Minutes These Minutes were confirmed by City Council on October 29, 2002. Agenda Index MINUTES OF THE COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF TORONTO TUESDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2002, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2002, AND THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2002 City Council met in the Council Chamber, City Hall, Toronto. CALL TO ORDER 7.1 Deputy Mayor Ootes took the Chair and called the Members to order. The meeting opened with O Canada. 7.2 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Councillor Disero, seconded by Councillor Nunziata, moved that the Minutes of the Special meeting of Council held on the 30th and 31st days of July, and the 1st of August, 2002, be confirmed in the form supplied to the Members, which carried. PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 7.3 Councillor Feldman presented the following Deferred Clauses and New Reports for consideration by Council: Deferred Clauses: Report No. 9 of The Administration Committee, Clause No. 1(a), Report No. 10 of The Administration Committee, Clauses Nos. 3(a), 4(a), 26(a) and 34(a), 2 Minutes of the Council of the City of Toronto October 1, 2 and 3, 2002 Joint Report No. 2 of The Policy and Finance Committee and The Works Committee, Clause No. 1(a), and Report No. 8 of The Humber York Community Council, Clause No. 1(a). New Reports: Report No. 13 of The Policy and Finance Committee, Report No. 8 of The Economic Development and Parks Committee, Report No. 10 of The Planning and Transportation Committee, Report No. -

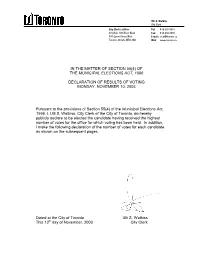

2003 Clerk's Official Declaration of Results

Ulli S. Watkiss City Clerk City Clerk’s Office Tel: 416-392-8010 City Hall, 10th Floor West Fax: 416-392-2980 100 Queen Street West E-mail: [email protected] Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Web: www.toronto.ca IN THE MATTER OF SECTION 55(4) OF THE MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS ACT, 1996 DECLARATION OF RESULTS OF VOTING MONDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2003 Pursuant to the provisions of Section 55(4) of the Municipal Elections Act, 1996, I, Ulli S. Watkiss, City Clerk of the City of Toronto, do hereby publicly declare to be elected the candidate having received the highest number of votes for the office for which voting has been held. In addition, I make the following declaration of the number of votes for each candidate as shown on the subsequent pages. Dated at the City of Toronto Ulli S. Watkiss This 13th day of November, 2003 City Clerk MAYOR CANDIDATE NAME VOTES ELECTED DAVID MILLER 299385 X JOHN TORY 263189 BARBARA HALL 63751 JOHN NUNZIATA 36021 TOM JAKOBEK 5277 DOUGLAS CAMPBELL 2197 AHMAD SHEHAB 2084 JAIME CASTILLO 1616 LUIS SILVA 1305 DON ANDREWS 1220 TIMOTHY MCAULIFFE 821 KEVIN CLARKE 804 JOHN HARTNETT 803 GARY BENNER 802 ALBERT HOWELL 717 JOHN JAHSHAN 703 MICHAEL BRAUSEWETTER 672 DAVID LICHACZ 659 RAM NARULA 645 ELIAS MAKHOUL 644 DANIEL POREMSKI 627 RONALD GRAHAM 619 FEN PETERS 598 DURI NAIMJI 569 SCOTT YEE 551 MONOWAR HOSSAIN 537 AXCEL COCON 498 BEN KERR 433 ALEKSANDAR GLISIC 420 MITCH GOLD 412 HASHMAT SAFI 383 SIMON SHAW 376 PATRICIA O'BEIRNE 358 ABEL VAN WYK 332 BENJAMIN MBAEGBU 288 GERALD DEROME 278 PAUL LEWIN 271 RABINDRA PRASHAD 271 HARDY DHIR 199 KENDAL CSAK 193 MEHMET YAGIZ 193 RICHARD WESTON 133 RATAN WADHWA 121 BARRY PLETCH 110 11/13/2003 Page 1 of 10 COUNCILLOR WARD NO. -

This Is a Proof

The Real Story Behind Leroy Leroy St Germain There are individuals and groups who political vendetta against Bussin. The large part our trusted media had can’t always get away with what they Nobody is accusing Leroy of being a in slamming the door of political want without consequences. These Bussin-fan before all of this hit, but office on former beach-favourite, groups or individuals do not want to that is what made him the perfect Sandra Bussin is a very important part be blamed for a smear campaign that publisher to be a fall guy. In addition, of this story, especially regarding the only works when a trusted neutral it is alleged that the owners of the Boardwalk/BBQ pub at the foot of source such as a newspaper does it Coxwell Avenue. Leroy (the owner of The Politician (Sandra) for them. If little Johnny called Mary a Ward32.ca), whose credit rating is gardening tool. We do not give it any non-existent at best, (most likely notice. But if the Toronto Star calls terrible) was the perfect lackey in this Mary a little gardening tool, we little scheme as he was in the position believe because we assume that the to offer the services of being a small Toronto Star does not want to be part of the media. He could do so sued. This fear of a lawsuit keeps more easily without the legal local media in check. With the web responsibilities and assets faced by there is no way to stop crazy talk. larger, more reputable publications even Wikipedia can be rewritten by like The Toronto Star, etc. -

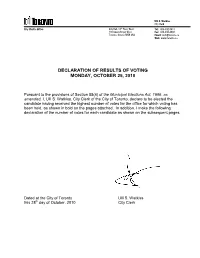

2010 Clerk's Official Declaration of Election Results

Ulli S. Watkiss City Clerk City Clerk’s Office City Hall, 13th Floor, West Tel: 416-392-8011 100 Queen Street West Fax: 416-392-4900 Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 Email: [email protected] Web: www.toronto.ca DECLARATION OF RESULTS OF VOTING MONDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2010 Pursuant to the provisions of Section 55(4) of the Municipal Elections Act, 1996, as amended, I, Ulli S. Watkiss, City Clerk of the City of Toronto, declare to be elected the candidate having received the highest number of votes for the office for which voting has been held, as shown in bold on the pages attached. In addition, I make the following declaration of the number of votes for each candidate as shown on the subsequent pages. Dated at the City of Toronto Ulli S. Watkiss this 28th day of October, 2010 City Clerk MAYOR CANDIDATE NAME VOTES ELECTED Rob Ford 383501 X George Smitherman 289832 Joe Pantalone 95482 Rocco Rossi 5012 George Babula 3273 Rocco Achampong 2805 Abdullah-Baquie Ghazi 2761 Michael Alexander 2470 Vijay Sarma 2264 Sarah Thomson 1883 Jaime Castillo 1874 Dewitt Lee 1699 Douglas Campbell 1428 Kevin Clarke 1411 Joseph Pampena 1319 David Epstein 1202 Monowar Hossain 1194 Michael Flie 1190 Don Andrews 1032 Weizhen Tang 890 Daniel Walker 804 Keith Cole 801 Michael Brausewetter 796 Barry Goodhead 740 Tibor Steinberger 735 Charlene Cottle 733 Christopher Ball 696 James Di Fiore 655 Diane Devenyi 629 John Letonja 592 Himy Syed 582 Carmen Macklin 575 Howard Gomberg 477 David Vallance 444 Mark State 438 Phil Taylor 429 Colin Magee 401 Selwyn Firth 394 Ratan Wadhwa 290 Gerald Derome 251 10/28/2010 Page 1 of 14 COUNCILLOR WARD NO. -

Both Right Wing and Left Wing Councillors Took Hits

GT2 H TORONTO STAR H TUESDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2010 ON ON0 GTA VOTES Joe Pantalone officially enters the oping facilities like BMO Field and RACE FOR THE MAYOR’S CHAIR 2010 race. The Ward 19, Trinity-Spadi- Allstream Centre. na councillor says the city Jan. 14: A Toronto Star-Angus PATTY WINSA 10 per cent. nounces he will not run, despite should develop more Reid poll has Smitherman with 44 URBAN AFFAIRS REPORTER Jan. 5, 2010: Giorgio Mammoliti, polls that suggest he would be private-sector per cent, followed by Adam Dec. 14, 2009: Rocco Rossi declares councillor for Ward 7 York West, a front-runner over rival for- partnerships, as Giambrone with 17 per cent his mayoral ambitions during a files papers to run with a promise to mer Liberal deputy premier he did as chair (Giambrone has not yet de- speech at Nathan Phillips Square. “to tame the Godzilla” – a reference George Smitherman. of Exhibition clared). Rossi polls at 15 per cent, He positions himself as a fiscal to the city’s ballooning budget. Jan. 8: Smitherman Place’s board Pantalone at 5 per cent and conservative, promising to sell off Jan. 7, 2010: John Tory, who lost to registers to run. of governors, Mammoliti at 4 per cent. 58 per Toronto Hydro and cut his salary by Mayor David Miller in 2003, an- Jan. 13: Deputy Mayor while devel- cent wwere undecided. STEELES AVE. W. STEELES AVE. E. Ward Riding T. 24 T. 39 CNR H 1 + 2 Etobicoke North . 1 NGE S u E m FINCH AVE. -

Tabia-Resourceguide09-Web.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS TORONTO/TABIA FACTSHEET _________________________________________________ 2 THE BIA STORY __________________________________________________________ 3 PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF TABIA __________________________________________ 4 TABIA ORGANIZATIONAL CHART ______________________________________________ 5-7 TABIA COMMITTEES Tax _______________________________________________________________ 8-9 Marketing & Communications ______________________________________________ 10 Tourism ____________________________________________________________ 11 Transportation ________________________________________________________ 12-13 Task Force on Crime ____________________________________________________ 14 TABIA WEBSITE _________________________________________________________ 15 TABIA MILESTONES AND ACHIEVEMENTS ________________________________________ 16-17 GREENTBIZ ____________________________________________________________ 18 TABIA DISCOUNTS & SAVINGS PROGRAMS Savings for BIA Boards __________________________________________________ 19-20 Savings for Member Businesses ____________________________________________ 21-22 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMMUNITY SUPPORT PROJECT ___________________________ 24 ACCESSIBILITY FOR ONTARIANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT _____________________________ 25 CITY OF TORONTO BIA OFFICE Commercial Area Advisors ________________________________________________ 26-27 Community Advisor Designers ______________________________________________ 26-27 Councillors __________________________________________________________ -

What's on at Applegrove

APPLEGROVE COMMUNITY COMPLEX 60 Woodfield Road, Toronto, Ontario M4L 2W6 Tel: 416-461-8143 Fax: 416-461-5513 www.ApplegroveCC.ca “TOGETHER, BUILDING OUR COMMUNITY” Board of Directors Meeting AGENDA – Monday, October 20, 2014 If you cannot attend, please call the office with your regrets. Applegrove’s mission is to be a neighbourhood partnership fostering community through social and informative programs for individuals and families. 6:45 Optional Light Supper 7:00 1. Call to Order/Adoption of Agenda 2. Welcome and Introductions 3. Declaration of Conflicts of Interest 4. Timekeeper 5. Volunteer Hours 6. Donation Envelope 7. Minutes 7.1. Minutes of the May 26 Board of Directors Meeting (Document 7.1): to be accepted 7.2. Minutes of the September 29 Board of Directors Meeting (Document 7.2): to be accepted 7:05 8. Strategic Planning 8.1. Presentation (Document to be circulated by e-mail and at the meeting) 8.2. Follow-up from September Board Meeting 8.3. Next Steps 7:30 9. Edgewood: programming options until church is available: for discussion and direction 8:00 10. Finance and Fundraising 10.1. 2014 Year to Date Statistics (Document 11.1): for information 10.2. 2014 Year to Date Financial Report: (To be distributed by e-mail and at the meeting) for information and endorsement 10.3. 2015 Program Budgets (Document 11.3): for information and endorsement 10.4. Fundraising and Event Calendar (Document 11.4): for information 10.5. Children’s Services Budget Submission (information included in 2015 program budgets): to be endorsed Charitable Number: 10671 8943 RR0001 Applegrove Board Meeting Agenda October 20, 2014 2 8:30 11. -

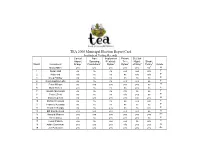

2006 Candidate Grades

TEA 2006 Municipal Election Report Card Incumbent Voting Records Cancel Ban Implement Private St.Clair Airport Spraying Pesticide Tree Right- Shade Ward Incumbent Bridge1 Dandelions2 Bylaw3 Bylaw4 of-Way5 Policy6 Grade Mayor Miller yes yes yes yes yes n/a7 A 1 Suzan Hall no no no yes yes n/a F 2 Rob Ford n/a no no no n/a n/a F 3 Doug Holiday no no no no no no F 4 Gloria Lindsay Luby no no no yes yes no F 5 Peter Milczyn no yes yes yes yes no B 6 Mark Grimes yes no no no yes no F 7 Giorgio Mammoliti no no no n/a no no F 8 Peter LiPreti no no no n/a yes no F 9 Maria Augimeri no yes yes yes n/a yes B 10 Michael Feldman no no no no yes n/a F 11 Frances Nunziata no no no no no no F 12 Frank Di Giorgio no no yes no no n/a F 13 Bill Saundercook yes yes yes yes yes no A 15 Howard Moscoe yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 16 Karen Stintz no no yes yes yes no C 17 Cesar Palacio yes no yes yes no n/a C 18 Adam Giambrone yes yes yes n/a yes yes A 19 Joe Pantalone yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ Cancel Ban Implement Private St.Clair Airport Spraying Pesticide Tree Right- Shad Ward Incumbent Bridge1 Dandelions2 Bylaw3 Bylaw4 of-Way5 Policy6 Grade 21 Joe Mihevc yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 22 Michael Walker yes yes yes yes no no B 23 John Filion yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 24 David Shiner no no no no yes n/a7 F 25 Clifford Jenkins yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 26 Jane Pitfield yes yes yes yes yes n/a A 27 Kyle Rae yes yes yes yes yes n/a A 28 Pam McConnell yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 29 Case Ootes no no no no no n/a F 30 Paula Fletcher yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 31 Janet Davis yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 32 Sandra Bussin yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 33 Shelley Carroll yes yes yes yes yes n/a A 34 Denzil Minnan-Wong no no no no yes no F 36 Brian Ashton yes n/a n/a no yes no D 37 Michael Thompson yes no yes no yes no D 38 Glenn De Baeremaeker yes yes yes yes yes n/a A 39 Mike Del Grande no no no yes yes no F 40 Norman Kelly no no no no yes no F 42 Raymond Cho yes yes yes yes yes yes A+ 1 December 3, 2003. -

2014 Ontario Civic Elections

2014 Ontario Civic Elections City of Toronto Total Vote Declared Candidate Office Votes Percent ELECTED Doug Ford Mayor 10,870 35.9% Olivia Chow Mayor 8,444 27.9% John Tory Mayor 7,870 26.0% D!ONNE Renée Mayor 425 1.4% Ari Goldkind Mayor 217 0.7% Morgan Baskin Mayor 198 0.7% Kevin Clarke Mayor 153 0.5% Matthew Crack Mayor 145 0.5% Selina Chan Mayor 143 0.5% Mike Gallay Mayor 100 0.3% Troy Young Mayor 90 0.3% Said Aly Mayor 86 0.3% Mohammad Okhovat Mayor 82 0.3% Veerayya Kembhavimath Mayor 73 0.2% Michael Gordon Mayor 72 0.2% Christopher Ball Mayor 55 0.2% Dewitt Lee Mayor 54 0.2% George Dedopoulos Mayor 53 0.2% Mark Cidade Mayor 52 0.2% Rocco Di Paola Mayor 51 0.2% Daniel Walker Mayor 51 0.2% Leo Gambin Mayor 50 0.2% Gary McBean Mayor 45 0.1% Frank Burgess Mayor 44 0.1% Steven Lam Mayor 44 0.1% Charles Huang Mayor 43 0.1% Dave McKay Mayor 42 0.1% Don Andrews Mayor 41 0.1% Jeff Billard Mayor 39 0.1% Oweka-Arac Ongwen Mayor 37 0.1% Chinh Huynh Mayor 33 0.1% Diana Maxted Mayor 33 0.1% Matthew Wong Mayor 33 0.1% Robb Johannes Mayor 32 0.1% Michael Tramov Mayor 30 0.1% Monowar Hossain Mayor 28 0.1% Radu Popescu Mayor 27 0.1% Jonathan Bliguin Mayor 26 0.1% Michael Nicula Mayor 24 0.1% Jonathan Glaister Mayor 23 0.1% Hïmy Syed Mayor 21 0.1% Christina Van Eyck Mayor 20 0.1% 2014 Ontario Civic Elections Chai Kalevar Mayor 19 0.1% Ramnarine Tiwari Mayor 19 0.1% Donovan Searchwell Mayor 18 0.1% Michael Tasevski Mayor 18 0.1% Lee Romanov Mayor 17 0.1% Jim Ruel Mayor 15 0.0% Tibor Steinberger Mayor 15 0.0% Jon Karsemeyer Mayor 14 0.0% Matt Mernagh -

Folder E1 – Parking Annual Report Examples

CITY OF LINCOLN - PARKING SYSTEM ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2005 Table of Contents CATEGORY PAGE Mission and Vision Statements 2 Message from the Parking Manager 3 Parking System Organization 4 Financial Overview 5-7 Utilization Study 8 Carriage Park 9-10 Center Park 11-12 Cornhusker 13-14 Haymarket 15-16 Market Place 17-18 Que Place 19-20 University Square 21-22 Transient Ticket Analysis 23 Duration of Stay Report 24 Parking Programs and Specials 25-26 Validation Sales Comparisons 27 Husker Football 28-29 Violations 30-32 Appendix Space Allocation 33-35 Mission “The Parking Section is defined by using appropriate strategies and oversight to promote compliance with its mission and related goals. This is done by supporting existing and future land uses, assisting the City’s economic development initiatives, and preserving parking by providing adequate and high quality parking resources and related services for all users while maintaining and/or increasing revenues to support future parking development.” Vision “To protect the City’s investment in the parking system by maintaining and improving on a safe, reliable, and efficient parking facilities and equipment. There will be a continuing need to maintain and improve the City’s existing and future parking facilities and equipment. This will be accomplished by utilizing the necessary training, technologies, and modern equipment. The City of Lincoln’s Parking Section will meet escalating public demands, by increasing the system’s ability to be more efficient, accountable, and responsive. The parking system will continue to efficiently serve the public with the highest standards of quality, safety, and responsiveness while working to increase public parking effectiveness.” page 2 Message from the Parking Manager I would like to present you the Public Works and Utilities Parking Section's first "official" annual report.