Harriet Monroe's Entrepreneurial Triumphs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

Edited by Harriet Monroe

VOL. VIII NO. II Edited by Harriet Monroe MAY 1916 Baldur—Holidays—Finis Allen Upward 55 May in the City .... Max Michelson 63 The Newcomers — Love-Lyric — Midnight — The Willow Tree—Storm—The Red Light—In the Park—A Hymn to Night. To a Golden-Crowned Thrush . Richard Hunt 68 Sheila Eileen—Carnage ...... Antoinette DeCoursey Patterson 69 Indiana—An Old Song Daphne Kieffer Thompson 70 Forgiveness .... Charles L. O'Donnell 72 Sketches in Color Maxwell Bodenheim 73 Columns of Evening—Happiness—Suffering—A Man to a Dead Woman—The Window-Washers—The Department Store Pyrotechnics I-III ..... Amy Lowell 76 To a Flower Suzette Herter 77 A Little Girl I-XIII .... Mary Aldis 78 Editorial Comment 85 Down East Reviews 90 Chicago Granite—The Independents—Two Belgian Poets Our Contemporaries 103 A New School of Poetry—The Critic's Sense of Humor Notes 107 Copyright 1916 by Harriet Monroe. All rights reserved. 543 CASS STREET, CHICAGO $1.50 PER YEAR SINGLE NUMBERS, 15 CENTS Published monthly by Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1025 Fine Arts Building, Chicago. Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, Chicago VOL. VIII No. II MAY, 1916 BALDUR OLD loves, old griefs, the burthen of old songs That Time, who changes all things, cannot change : Eternal themes! Ah, who shall dare to join The sad procession of the kings of song— Irrevocable names, that sucked the dregs Of sorrow from the broken honeycomb Of fellowship?—or brush the tears that hang Bright as ungathered dewdrops on a briar? Death hallows all; but who will bear with me To breathe a more heartrending -

Little Magazines Suzanne W

14 Little Magazines Suzanne W. Churchill The Little Magazine and the Making of New Artistic Forms New York, 1917: Patriotism is surging as fighting rages across Europe and the United States gears up to join the Great War. Democracy is at risk. To strengthen its foothold and “bring democracy to the art world,” a group of Americans and Europeans form the Society of Independent Artists and host an unprecedented event: an art exhibition with no jury or prizes, no arbiters of taste or hierarchies of value (Watson 280–81). For a $6 fee, any artist can exhibit work at the Grand Central Palace. French émigré and agent provocateur Marcel Duchamp determines to test the Society’s democratic principles. Under the pseudonym “R. Mutt,” he submits an overturned urinal, set on a black pedestal and entitled Fountain. An argument erupts among the directors about whether to accept the submission: one faction condemns it as an obscene joke, while the other defends it as an expression of artistic freedom. In the heat of the moment, no one recognizes that it is both. The board rejects Fountain, with director William Glackens declaring, “It is, by no definition, a work of art” (qtd. in Watson 314). The urinal disappeared, and no one knows what exactly happened to it (Watson 318). But Fountain was preserved in a photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz and pub- lished in the Blindman, a little magazine issued shortly after the Independents exhibi- tion opened. By publishing this photograph, along with essays defending the artistic legitimacy of Fountain, the Blindman initiated a process through which an irreverent new form – in this case a utilitarian, mechanically produced object – could be recog- nized, circulated, and ultimately sanctified as one of the most important artworks of the twentieth century. -

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe July 1918

Vol. XII No. IV A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe July 1918 Prairie by Carl Sandburg Kaleidoscope by Marsden Hartley D. H. Lawrence, Eloise Robinson, William Carlos Williams Poems by Children 543 Cass Street. Chicago $2.00 per Year Single Numbers 20c There ia no magazine published in this country which has brought me such delight as your POETRY. I loved it from the beginning of its existence, and 1 hope that it may live forever. A Subscriber POETRY for JULY, 1918 PAGE Prairie Carl Sandburg 175 Island Song Robert Paini Scripps 185 Moonrise—People D.H. Lawrence 186 Sacrament Pauline D. Partridge 187 The Trees Eloise Robinson 188 Crépuscule Maxwell Struthers Burt 189 There Was a Rose—An Old Man's Weariness Arthur L. Phelps 190 The Screech Owl J.E.Scruggs 191 Le Médecin Malgré Lui William Carlos Williams 192 Plums P. T. R. 193 • To a Phrase ' Hazel Hall 194 Kaleidoscope Marsden Hartley 195 In the Frail Wood—Spinsters—Her Daughter—After Battle I-III Poems by Children : Fairy Footsteps I-VIII Hilda Conkling 202 Sparkles I-III Elmond Franklin McNaught 205 In the Morning Juliana Allison Bond 205 Ripples I-IV Evans Krehbiel 206 Mr. Jepson's Slam H.M. 208 The New Postal Rate H. M. 212 Reviews: As Others See Us Alfred Kreymborg 214 Mr. O'Neil's Carvings Emanuel Carnevali 225 Correspondence: Of Puritans, Philistines and Pessimists .... A. CH. 228 An Anthology of 1842 Willard Wattles 230 Notes and Books Received 231 Manuscripts must be accompanied by a stamped and self-addressed envelope. -

Harriet Monroe's Abraham Lincoln

Harriet Monroe’s Abraham Lincoln MARK B. POHLAD It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature. —Henry James In 1919, when Harriet Monroe reviewed a new stage hit Abraham Lincoln, by British playwright John Drinkwater, it was already a Broad- way smash and would run continuously for five years in nearly every major American city.1 Although audiences were clearly thrilled, Mon- roe resented the play and found it completely unconvincing: Mr. Drinkwater picks [Lincoln] up out of his own place, and sets him down in a manufactured milieu, where the people do not think his thoughts nor speak his tongue, and even the chairs don’t look natural.2 Her last observation is so withering it deserves a permanent place in theater history.3 What could have so upset Monroe about a portrayal of Lincoln? And how did she come to be so invested in the representation of Illinois’ most famous son? What was her relationship to Lincoln’s memory, and how did it influence her editorial entrepreneurship? Monroe was instrumental in shaping the modern literary treatment of Abraham Lincoln (fig. 1). She revered his memory and advanced the careers of authors who engaged Lincoln as a subject in their work. 1. Roy P. Basler, “Lincoln and American Writers,” Papers of the Abraham Lincoln Asso- ciation 7 (1985), 9. 2. Harriet Monroe, “Review: A Lincoln Primer,” Poetry: A Magazine of Verse 15 (December 1919), 161. 3. Monroe apparently did not read Drinkwater’s introduction to the published ver- sion of the play in which the author graciously confesses his limitations: “I am an Englishman, and not a citizen of the great country that gave Lincoln birth. -

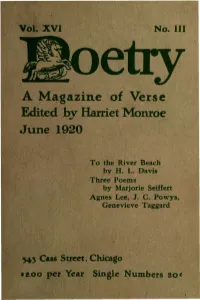

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe June 1920

Vol. XVI No. III A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe June 1920 To the River Beach by H. L. Davis Three Poems by Marjorie Seiffert Agnes Lee, J. C. Powys, Genevieve Taggard 543 Cass Street. Chicago $2.00 per Year Single Numbers 20c Your magazine is admirably American in spirit—modern cosmopolitan America, not the insular America of bygone days. Evelyn Scott Vol. XVI No. III POETRY for JUNE, 1920 PAGE To the River Beach H. L. Davis 117 In this Wet Orchard—Stalks of Wild Hay—Baking Bread —The Rain-crow—The Threshing-floor—From a Vine yard—The Market-gardens—October: "The Old Eyes"— To the River Beach Sleep Poems Agnes Lee 128 Old Lizette on Sleep—The Ancient Singer—Mrs. Malooly —The Ilex Tree Three Poems Marjorie Allen Sieffert 131 Cythaera and the Leaves—Cythaera and the Song— C3'thaera and the Worm Transition Eleanor Hammond 133 Surrender Irwin Granich 134 Out of the Dark A. N. 135 Songs I-IV Glenn Ward Dresbach 136 The Riddle John Cowper Powys 138 The Shepherd Hymn Gladys Hensel 139 Cold Hills Janet Loxley Lewis 140 Austerity—The End of the Age—Geology—Fossil From the Frail Sea Genevieve Taggard 142 Men or Women? H. M. 146 Discovered in Paris H. M. Reviews: Starved Rock M. A. Seiffert 151 Perilous Leaping Marion Strobel 157 Out of the Den Babette Deutsch 159 Black and Crimson Marion Strobel 162 Standards of Literature .... Richard Aldington 164 Our Contemporaries: New English Magazines H. M. 168 Correspondence: ManuscriptRiddles s anmusdt bRunee accompanies . d. -

Modern American Poetry and the Protestant Establishment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Modern American Poetry and the Protestant Establishment Jonathan Fedors University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Fedors, Jonathan, "Modern American Poetry and the Protestant Establishment" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 856. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/856 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/856 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern American Poetry and the Protestant Establishment Abstract Modern American Poetry and the Protestant Establishment argues that secularization in modern American poetry must be understood with reference to the Protestant establishment. Drawing on interdisciplinary work revising the secularization thesis, and addressed to modern poetry and poetics, Americanist, and modernist scholars, the dissertation demonstrates that the tipping point of secularization in modern American poetry was not reached at the dawn of modernism, as most critics have assumed, but rather in the decades following World War II. From the 1890s to the early 1960s, poets such as Robert Frost, Marianne Moore, James Weldon Johnson, and Harriet Monroe - founding editor of the important little magazine Poetry: A Magazine of Verse - identified the establishment with the national interest, while fashioning gestures of openness toward its traditional targets of discrimination, particularly Roman Catholics, African Americans, and Jews. These gestures acknowledged the establishment's weakened position in the face of internal division, war, racial strife, economic inequality, and mounting calls for cultural pluralism. -

Chicago 1 Chicago

Chicago 1 Chicago Chicago City City of Chicago Clockwise from top: Downtown Chicago, the Chicago Theatre, the 'L', Navy Pier, Millennium Park, the Field Museum, and Willis Tower. Flag Seal Nickname(s): The Windy City, Chi-Town, Chi-City, Hog Butcher for the World, The City That Works, and others found at List of nicknames for Chicago Motto: Latin: Urbs in Horto (City in a Garden), I Will Location in the Chicago metropolitan area and Illinois Chicago 2 Location in the United States [1] [1] Coordinates: 41°52′55″N 087°37′40″W Coordinates: 41°52′55″N 087°37′40″W Country United States State Illinois Counties Cook, DuPage Settled 1770s Incorporated March 4, 1837 Named for Miami-Illinois: shikaakwa ("Wild onion") Government • Type Mayor–council • Mayor Rahm Emanuel (D) • City Council 50 aldermen Area • City 234.0 sq mi (606.1 km2) • Land 227.2 sq mi (588 km2) • Water 6.9 sq mi (18 km2) 3.0% • Urban 2,122.8 sq mi (5,498 km2) • Metro 10,874 sq mi (28,160 km2) Elevation 597 ft (182 m) Population (2012 Estimate) • City 2,714,856 • Rank 3rd US • Density 11,864.4/sq mi (4,447.4/km2) • Urban 8,711,000 • Metro 9,461,105 Demonym Chicagoan Time zone CST (UTC−06:00) • Summer (DST) CDT (UTC−05:00) Area code(s) 312, 773, 872 [2] FIPS code 17-14000 [3] GNIS feature ID 428803 Chicago 3 [4] Website www.cityofchicago.org Chicago ( i/ʃɪˈkɑːɡoʊ/ or /ʃɪˈkɔːɡoʊ/) is the third most populous city in the United States. -

In This Issue

The Ol’ Pioneer The Magazine of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Volume 22 : Number 2 www.GrandCanyonHistory.org Spring 2011 In This Issue Book Review ............................................... 3 The Infinities of Beauty and Terror ........ 4 Louis Schellback’s Log Books, Part 3 .....11 President’s Letter The Ol’ Pioneer The Magazine of the Grand Canyon Historical Society Calling All Grand Canyon Historians!! Volume 22 : Number 2 Spring 2011 Planning and coordination is well under way for the next Grand Canyon History Symposium scheduled for January 2012. We recently sent out a Call for u Papers asking Grand Canyon historians, researchers and writers to submit pro- The Historical Society was established posals to present at the symposium. If you have a Grand Canyon history topic in July 1984 as a non-profit corporation that you have researched (or know somebody working on an interesting topic), to develop and promote appreciation, we strongly encourage you to submit a proposal. The presenters at the last under-standing and education of the symposium were a nice mix of historians, river runners, hikers, writers, park earlier history of the inhabitants and employees and enthusiastic amateur historians - we expect to have a similar important events of the Grand Canyon. mix this year. So, please get the word out – the deadline for submitting propos- The Ol’ Pioneer is published by the als is June 15. Additional details about the symposium and how to submit a GRAND CANYON HISTORICAL proposal can be found on the GCHS website (http://www.grandcanyonhis- SOCIETY in conjunction with The tory.org/). Bulletin, an informational newsletter. -

Guide to the Harriet Monroe Papers 1873-1944

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Harriet Monroe Papers 1873-1944 © 2015 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Biographical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 6 Series I: Correspondence 6 Subseries 1: General Correspondence 7 Subseries II: Family and Miscellaneous Correspondence 19 Series II: Diaries, Photographs and Memorabilia 20 Series III: Harriet Monroe’s Estate 24 Series IV: A Poet’s Life 25 Subseries 1: Geraldine Udell’s Correspondence 25 Subseries 2: Drafts and Notes 27 Series V: Writings 28 Subseries 1: Essays and Lectures on English Poetry and Arts 28 Subseries 2: Essays and Short Stories 29 Subseries 3: Lectures and Lecture Material 32 Subseries 4: Editorials and Reviews from Poetry, Other Writings 32 Subseries 5: Plays 33 Subseries 6: The Columbian Ode 34 Subseries 7: Poetry in Manuscript, Arranged by First Line 34 Subseries 8: Proofs and galleys of Monroe’s Poetry 43 Series VI: The New Poetry 44 Subseries 1: First edition 44 Subseries 2: Second Edition 46 Subseries 3: Third Edition, Poems for Every Mood 48 Series VII: Clippings 50 Series VIII: Oversize 51 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.MONROE Title Monroe, Harriet. Papers Date 1873-1944 Size 17 linear feet (24 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Harriet Monroe (1860-1936), poet and editor and founder of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse. Contains correspondence; manuscripts; diaries; legal documents; memorabilia, photographs; and news clippings documenting Monroe’s life and career. -

Women Editing Modernism: "Little" Magazines and Literary History

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1995 Women Editing Modernism: "Little" Magazines and Literary History Jayne Marek Franklin College Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Marek, Jayne, "Women Editing Modernism: "Little" Magazines and Literary History" (1995). Literature in English, North America. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/13 \XlOMEN EDITING MODERNISM This page intentionally left blank ~OMEN EDITING MODERNISM "Little" Magazines & Literary History jAYNE E. MAREK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1995 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Sociery, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marek, Jayne E., 1954- Women Editing Modernism : "little" magazines and literary history I Jayne E. Marek P· em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8131-1937-5 (alk. paper). - ISBN 0-8131-0854-3 (alk. paper) 1. American literature-20th century-History and criticism. 2. Modernism (Literature)-United States. -

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe September 1921

Vol. XVIII No. VI A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe September 1921 Poems by Paul Fort Tr'd by John Strong Newberry Spinners By Marya Zaturensky Still-hunt, by Glenway Wescott Charles the Twelfth, by Rilke Tr'd by Jessie Lemont 543 Cass Street Chicago $3.00 per Year Single Numbers 25c POETRY A MAGAZINE OF VERSE VOLUME XVI11 VOLUME XVIII April-September, 1921 Edited by Harriet Monroe 543 CASS STREET CHICAGO Copyright, 1921, by Harriet Monroe Editor HARRIET MONROE Associate Editors ALICE CORBIN HENDERSON MARION STROBEL Business Manager MILA STRAUB Advisory Committee HENRY B. FULLER EUNICE TIETJENS Administrative Committee WILLIAM T. ABBOTT CHARLES H. HAMILL TO HAVE GREAT POETS THERE MUST BE GREAT AUDIENCES TOO Whitman SUBSCRIBERS TO THE FUND Mr. Howard Shaw Mrs. Bryan Lathrop Mr. Arthur T. Aldis Mr. Martin A. Ryerson Mr. Edwin S. Fetcher Mrs. Charles H. Hamill Hon. John Barton Payne Mrs. Emmons Blaine (4) Mr. Thomas D. Jones Mr. Wm. S. Monroe Mr. Charles Deering Mr. E. A. Bancroft Mrs. W. F. Dummer Mr. C. L. Hutchinson Mrs. Wm. J. Calhoun Mr. Arthur Heun Mrs. P. A. Valentine Mr. Edward F. Carry Mr. Cyrus H. McCormick (2) [iMr] . F. Stuyvesant Peabody Mr. Horace S. Oakley Miss Dorothy North Mr. Eames MacVeagh Mrs. F. Louis Slade Mr. Charles G. Dawes Mrs. Julius Rosenwald Mr. Owen F. Aldis Mrs. Andrea Hofer Proudfoot Mr. Albert H. Loeb (2) Mrs. Arthur T. Aldis The Misses Skinner Mrs. George W. Mixter Misses Alice E. and Margaret D. Mrs. Walter S. Brewster Moran Mrs. Joseph N. Eisendrath Miss Mary Rozet Smith Mr.