EVALUATION the Municipal Development Program Final Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.3 Angola Road Network

2.3 Angola Road Network Distance Matrix Travel Time Matrix Road Security Weighbridges and Axle Load Limits For more information on government contact details, please see the following link: 4.1 Government Contact List. Page 1 Page 2 Distance Matrix Uige – River Nzadi bridge 18 m-long and 4 m-wide near the locality of Kitela, north of Songo municipality destroyed during civil war and currently under rehabilitation (news 7/10/2016). Road Details Luanda The Government/MPLA is committed to build 1,100 km of roads in addition to 2,834 km of roads built in 2016 and planned rehabilitation of 7,083 km of roads in addition to 10,219 km rehabilitated in 2016. The Government goals will have also the support from the credit line of the R. of China which will benefit inter-municipality links in Luanda, Uige, Malanje, Cuanza Norte, Cuanza Sul, Benguela, Huambo and Bié provinces. For more information please vitsit the Website of the Ministry of Construction. Zaire Luvo bridge reopened to trucks as of 15/11/2017, this bridge links the municipality of Mbanza Congo with RDC and was closed for 30 days after rehabilitation. Three of the 60 km between MCongo/Luvo require repairs as of 17/11/2017. For more information please visit the Website of Agencia Angola Press. Works of rehabilitation on the road nr, 120 between Mbanza Congo (province Zaire) and the locality of Lukunga (province of Uige) of a distance of 111 km are 60% completed as of 29/9/2017. For more information please visit the Website of Agencia Angola Press. -

Angola Food Security Update

Angola Food Security Update June 2004 USAID Funded Activity Prices of staple foods in Huambo remain stable due to improved trade flow from Kuanza Sul, Huila and Bie provinces In April 2004, FEWS NET conducted a short survey in the informal markets of Huambo, Huila and Luanda. Regional Trade Flows In May and June 2004, following requests from a few Increased trade flow since the main crop harvest NGOs, FEWS NET conducted a similar survey to in May/June 2004 monitor trade flows and market prices, now including Benguela and Uige provinces. This food security The demand for maize and beans in urban and update discusses the findings of this work. rural areas of Huambo and Bengula continues to attract supplies from Huila and Kuanza Sul Trade Flow and Maize Prices provinces. During the last two months, the supply of maize, sorghum and beans from Huila to Maize prices remain stable and further decline is Benguela increased substantially. Sorghum, expected which was almost not traded in April 2004, is now Prices of staple foods in local markets have an impact reaching the urban markets in Benguela. This on food security, as many vulnerable families rely on reflects good sorghum harvest in Huila, which is markets to supplement their food needs. Trade flows estimated to have increased by six percent – from and price analysis during May and June revealed two 33,000 MT in the 2002-03 season to 35,000 MT in major factors positively influencing food availability. the 2003-04 season. Farmers in Kaluqumbe, Firstly, continued trade activity between Huambo and Matala, Kipungo and Quilengues supply the bulk the neighbouring provinces is helping to stabilise food of the produces to Buenguela. -

A Crude Awakening

Dedicated to the inspiration of Jeffrey Reynolds ISBN 0 9527593 9 X Published by Global Witness Ltd P O Box 6042, London N19 5WP,UK Telephone:+ 44 (0)20 7272 6731 Fax: + 44 (0)20 7272 9425 e-mail: [email protected] a crude awakening The Role of the Oil and Banking Industries in Angola’s Civil War and the Plunder of State Assets http://www.oneworld.org/globalwitness/ 1 a crude awakening The Role of the Oil and Banking Industries in Angola’s Civil War and the Plunder of State Assets “Most observers, in and out of Angola, would agree that “There should be full transparency.The oil companies who corruption, and the perception of corruption, has been a work in Angola, like BP—Amoco, Elf,Total and Exxon and the critical impediment to economic development in Angola.The diamond traders like de Beers, should be open with the full extent of corruption is unknown, but the combination of international community and the international financial high military expenditures, economic mismanagement, and institutions so that it is clear these revenues are not syphoned corruption have ensured that spending on social services and A CRUDE AWAKENING A CRUDE development is far less than is required to pull the people of off but are invested in the country. I want the oil companies Angola out of widespread poverty... and the governments of Britain, the USA and France to co- operate together, not seek a competitive advantage: full Our best hope to ensure the efficient and transparent use of oil revenues is for the government to embrace a comprehensive transparency is in our joint interests because it will help to program of economic reform.We have and will continue to create a more peaceful, stable Angola and a more peaceful, encourage the Angolan Government to move in this stable Africa too.” direction....” SPEECH BY FCO MINISTER OF STATE, PETER HAIN,TO THE ACTION FOR SECRETARY OF STATE, MADELEINE ALBRIGHT, SUBCOMMITTEE ON FOREIGN SOUTHERN AFRICA (ACTSA) ANNUAL CONFERENCE, SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL OPERATIONS, SENATE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS, JUNE 16 1998. -

31 CFR Ch. V (7–1–05 Edition) Pt. 590, App. B

Pt. 590, App. B 31 CFR Ch. V (7–1–05 Edition) (2) Pneumatic tire casings (excluding tractor (C) Nharea and farm implement types), of a kind (2) Communities: specially constructed to be bulletproof or (A) Cassumbe to run when deflated (ECCN 9A018); (B) Chivualo (3) Engines for the propulsion of the vehicles (C) Umpulo enumerated above, specially designed or (D) Ringoma essentially modified for military use (E) Luando (ECCN 9A018); and (F) Sachinemuna (4) Specially designed components and parts (G) Gamba to the foregoing (ECCN 9A018); (H) Dando (f) Pressure refuellers, pressure refueling (I) Calussinga equipment, and equipment specially de- (J) Munhango signed to facilitate operations in con- (K) Lubia fined areas and ground equipment, not (L) Caleie elsewhere specified, developed specially (M) Balo Horizonte for aircraft and helicopters, and specially (b) Cunene Province: designed parts and accessories, n.e.s. (1) Municipalities: (ECCN 9A018); [Reserved] (g) Specifically designed components and (2) Communities: parts for ammunition, except cartridge (A) Cubati-Cachueca cases, powder bags, bullets, jackets, (B) [Reserved] cores, shells, projectiles, boosters, fuses (c) Huambo Province: and components, primers, and other det- (1) Municipalities: onating devices and ammunition belting (A) Bailundo and linking machines (ECCN 0A018); (B) Mungo (h) Nonmilitary shotguns, barrel length 18 (2) Communities: inches or over; and nonmilitary arms, (A) Bimbe discharge type (for example, stun-guns, (B) Hungue-Calulo shock batons, etc.), except arms designed (C) Lungue solely for signal, flare, or saluting use; (D) Luvemba and parts, n.e.s. (ECCNs 0A984 and 0A985); (E) Cambuengo (i) Shotgun shells, and parts (ECCN 0A986); (F) Mundundo (j) Military parachutes (ECCN 9A018); (G) Cacoma (k) Submarine and torpedo nets (ECCN (d) K. -

ANGOLA FOOD SECURITY UPDATE July 2003

ANGOLA FOOD SECURITY UPDATE July 2003 Highlights The food security situation continues to improve in parts of the country, with the overall number of people estimated to need food assistance reduced by four percent in July 2003 relieving pressure on the food aid pipeline. The price of the least-expensive food basket also continues to decline after the main harvest, reflecting an improvement in access to food. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the results of both the latest nutritional surveys as well as the trend analysis on admissions and readmissions to nutritional rehabilitation programs indicate a clear improvement in the nutritional situation of people in the provinces considered at risk (Benguela, Bie, Kuando Kubango). However, the situation in Huambo and Huila Provinces still warrants some concern. Household food stocks are beginning to run out just two months after the main harvest in the Planalto area, especially for the displaced and returnee populations. In response to the current food crisis, relief agencies in Angola have intensified their relief efforts in food insecure areas, particularly in the Planalto. More than 37,000 returnees have been registered for food assistance in Huambo, Benguela, Huila and Kuando Kubango. The current food aid pipeline looks good. Cereal availability has improved following recent donor contributions of maize. Cereal and pulse projections indicate that total requirements will be covered until the end of October 2003. Since the planned number of beneficiaries for June and July 2003 decreased by four percent, it is estimated that the overall availability of commodities will cover local food needs until end of November 2003. -

Situation Report

4BABAY ZIKA VIRUS SITUATION REPORT YELLOW FEVER 28 OCTOBER 2016 KEY UPDATES . Angola epidemiological update (as of 20 October): o The last confirmed case had symptom onset on 23 June. o Two new probable cases without a history of yellow fever vaccination were reported from Kwanza Sul province in the last week. o Phase two of the vaccination campaign is ongoing, targeting more than two million people in 10 provinces. Democratic Republic of the Congo epidemiological update (as of 26 October): o The last confirmed non-sylvatic case had symptom onset on 12 July. o A new confirmed, sylvatic case was reported from Bominenge Health Zone in Sud Ubangui province. o Fourteen probable cases remain under investigation. o The reactive campaign in Mushenge Health Zone in Kasai province, which began on 20 October, is ongoing. ANALYSIS . The majority of the probable cases in Angola have been ruled out as yellow fever cases by the Institut Pasteur of Dakar. They will remain classified as probable cases until a full battery of tests has been run to determine other possible causes of illness. Once the final results are received the cases will be reclassified. Coincidentally, a previously scheduled pre-emptive vaccination campaign is ongoing in Kwanza Sul province where two new probable cases were reported. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SITUATION Angola . Two new probable cases without a history of yellow fever vaccination were reported from Kwanza Sul province in the last week. Of the forty-five probable cases that were reported in the four weeks to 13 October: 31 have been discarded, two are undergoing further testing and 12 await classification by the committee (Fig. -

Return of Congolese Refugees to the DRC and Idps in The

FICSS in DOS Return of congolese refugees to the DRC and IDPs in the DRC Field Information and Coordination Support Section As of September 2006 Division of Operational Services Email : [email protected] !!! !!! Calabar !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! SUDANSUDAN !!! Juba !!! Port Harcourt !!! Bangassou !!! !!! BANGUIBANGUI !!! CENTRALCENTRAL Kumba CENTRALCENTRAL !!! CENTRALCENTRAL !!! CENTRALCENTRAL !!! CENTRALCENTRAL !!! CENTRALCENTRAL !!! CENTRALCENTRAL !!! CAMEROONCAMEROON !!! Yambio CAMEROONCAMEROON !!! CAMEROONCAMEROON !!! CAMEROONCAMEROON !!! CAMEROONCAMEROON !!! !!! Batouri !!! !!! Mabaye !!! !!! !!! Doumé !!! !!! Buea !!! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! !! AFRICANAFRICAN REP.REP. !!! !! Douala YAOUNDÉYAOUNDÉ !!! MALABOMALABO !!! Libenge !!! Niangara !!! Gemena !!! !!! Watsa !!! Arua !!! !!! !!! Sangmélima Ebolowa !!! !!! !!! !!! Buta !!! Gulu !!! Aketi EQUATEUREQUATEUR !!! !!! !!! Bumba DRC_Return&IDPs_Overview_A3LC.WOR !!! Lisala PROVINCEPROVINCE ORIENTALEORIENTALE EQUATORIALEQUATORIAL!!! EQUATORIALEQUATORIAL !!! EQUATORIALEQUATORIAL !!! EQUATORIALEQUATORIAL !!! EQUATORIALEQUATORIAL !!! !!! Oyem UGANDAUGANDA GUINEAGUINEA Basankusu !!! REP.REP. OFOF !!! Fort Portal !! Kisangani LIBREVILLELIBREVILLE !!! Jinja LIBREVILLELIBREVILLE THETHE CONGOCONGO KAMPALAKAMPALA !! Mbandaka !!! Entebbe !!! Boende !!! Ponthierville NORTHNORTH KIVU**KIVU** -

Angola Rapid Assessment and Gap Analysis: ANGOLA

Rapid Assessment Gap Analysis Angola Rapid Assessment and Gap Analysis: ANGOLA September 2015 Rapid Assessment and Gap Analysis - Angola Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 1: Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Country Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1.1. Geography and Demography overview ............................................................................................... 16 1.1.2. Political, economic and socio-economic conditions ............................................................................ 18 1.2. Energy Situation ........................................................................................................................................ 20 1.2.1. Energy Resources ................................................................................................................................. 20 1.2.1.1. Oil and Natural Gas -

Angola's Agricultural Economy in Brief'

"~ ANGOLA'S AGRICULTURAL ECONOMY IN BRIEF'. (Foreign Agr,ioultural Eoonomic Report) . USPMFAER-139 / Herbert H. Stein~r. W~shj.ngton, DC~ EC.onom'ic Rese9.rqh Servic:-.e. Sep .. 1977. (NAL Call No. A281 ;9.1Ag8F) 1.0 :; 11111:,8 111111:~ I~ IIB~ w t:: i~l~ ~ ~ 140 0 I\III~ ~"' - . \\\\I~ 1III1 1.4 111111.6 ANGOLA'S AGRICULTURAL ECONOMY IN BRIEF U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Foreign Agricultural Economic Report No. 139 NOTe' Names In parentheses are pre·mdependence names. ANGOLA'S AGRICULTURAL ECONOHY TN BRIEF. By Herbert H. Steiner, Foreign Demand and Competition Division, Eco nomic Research Service. Foreign Agricultural Economic Report No. 139. Washington, D.C. 20250 September 1977 \l ABSTRACT A short summary of the history, and a description of the physiography, climate, soils and vegetation, people, and economy of I Angola are followed by a report on the agri cultural sector as it existed just before independence in November 1975. Coffee was then the principal crop; corn and cassava were the staple foods. Other important crops were cotton! sisal, bananas, ~eans, and potatoes. Petroleum was the principal export, followed by coffee, diamonds, iron ore, fishmeal, cotton, and sisal. Keywords: Angola; Africa; Agricultural pro duction; Agricultural trade. ,) ! . : PREFAce Angola became independent on November 11, 1975. A devastating civil war accompanied the transition. The war and the exodus of most of the employees of the colonial Government interrupted the collection of statistics on production and trade. Because of the paucity of reliable data during and after the transi tion, this study is essentially a description of Angolan agriculture as it existed before independence. -

Angola Health System Assessment 2010

ANGOLA HEALTH SYSTEM ASSESSMENT 2010 July 2010 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Catherine Connor (Abt Associates Inc.), Denise Averbug (Abt Associates Inc.) and Maria Miralles (International Relief and Development) for the Health Systems 20/20 project. Mission The Health Systems 20/20 cooperative agreement, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) for the period 2006-2011, helps USAID-supported countries address health system barriers to the use of life-saving priority health services. Health Systems 20/20 works to strengthen health systems through integrated approaches to improving financing, governance, and operations, and building sustainable capacity of local institutions. July 2010 For additional copies of this report, please email [email protected] or visit our website at www.healthsystems2020.org Cooperative Agreement No.: GHS-A-00-06-00010-00 Submitted to: Robert Emrey, CTO Health Systems Division Office of Health, Infectious Disease and Nutrition Bureau for Global Health United States Agency for International Development Recommended Citation: Connor, Catherine, Denise Averbug, and Maria Miralles. July 2010. Angola Health System Assessment 2010. Bethesda, MD: Health Systems 20/20, Abt Associates Inc. Abt Associates Inc. I 4550 Montgomery Avenue I Suite 800 North I Bethesda, Maryland 20814 I P: 301.347.5000 I F: 301.913.9061 I www.healthsystems2020.org I www.abtassociates.com In collaboration with: I Aga Khan Foundation -

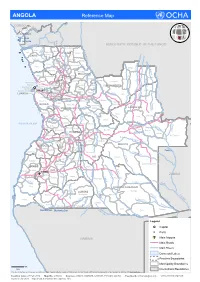

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

Angola Livelihood Zone Report

ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 ANGOLA Livelihood Zones and Descriptions November 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………................……….…........……...3 Acronyms and Abbreviations……….………………………………………………………………......…………………....4 Introduction………….…………………………………………………………………………………………......………..5 Livelihood Zoning and Description Methodology……..……………………....………………………......…….…………..5 Livelihoods in Rural Angola….………........………………………………………………………….......……....…………..7 Recent Events Affecting Food Security and Livelihoods………………………...………………………..…….....………..9 Coastal Fishing Horticulture and Non-Farm Income Zone (Livelihood Zone 01)…………….………..…....…………...10 Transitional Banana and Pineapple Farming Zone (Livelihood Zone 02)……….……………………….….....…………..14 Southern Livestock Millet and Sorghum Zone (Livelihood Zone 03)………….………………………….....……..……..17 Sub Humid Livestock and Maize (Livelihood Zone 04)…………………………………...………………………..……..20 Mid-Eastern Cassava and Forest (Livelihood Zone 05)………………..……………………………………….……..…..23 Central Highlands Potato and Vegetable (Livelihood Zone 06)..……………………………………………….………..26 Central Hihghlands Maize and Beans (Livelihood Zone 07)..………..…………………………………………….……..29 Transitional Lowland Maize Cassava and Beans (Livelihood Zone 08)......……………………...………………………..32 Tropical Forest Cassava Banana and Coffee (Livelihood Zone 09)……......……………………………………………..35 Savannah Forest and Market Orientated Cassava (Livelihood Zone 10)…….....………………………………………..38 Savannah Forest and Subsistence Cassava