Padre Island National Seashore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John C. Abbott Section of Integrative Biology 1

John C. Abbott Section of Integrative Biology (512) 232-5833, office 1 University Station #L7000 (512) 232-1896, lab The University of Texas at Austin (512) 475-6286, fax Austin, Texas 78712 USA [email protected] http://www.sbs.utexas.edu/jcabbott http://www.odonatacentral.org PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION Stroud Water Research Center, Philadelphia Academy of Sciences Postdoc, 1999 University of North Texas Biology/Ecology Ph.D., 1999 University of North Texas Biology/Ecology M.S., 1998 Texas A&M University Zoology/Entomology B.S., 1993 Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science, University of North Texas 1991 APPOINTMENTS 2006-present Curator of Entomology, Texas Natural Science Center 2005-present Senior Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences, UT Austin 1999-2005 Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences, University of Texas at Austin 2004-present Environmental Science Institute, University of Texas 2000-present Research Associate, Texas Memorial Museum, Texas Natural History Collections 1999 Research Scientist, Stroud Water Research Center, Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences 1997-1998 Associate Faculty, Collin County Community College (Plano, Texas) 1997-1998 Teaching Fellow, University of North Texas PUBLICATIONS Fleenor, S.B., J.C. Abbott, E. Wang. 2011. Seasonal appearance, diel flight activity, and geographic distribution of male Telegeusis texensis Fleenor and Taber (Coleoptera: Telegeusidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin. 65: 345-349. Abbott, J.C. 2011. The female of Leptobasis melinogaster González-Soriano (Odonata: Coenagrionidae). International Journal of Odonatology. 14: 171-174. Abbott, J.C. and T.D. Hibbitts. 2011. Cordulegaster sarracenia n. sp. (Odonata: Cordulegastridae) from east Texas and western Louisiana, with a key to adult Cordulegastridae of the New World. -

![[The Pond\. Odonatoptera (Odonata)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4965/the-pond-odonatoptera-odonata-114965.webp)

[The Pond\. Odonatoptera (Odonata)]

Odonatological Abstracts 1987 1993 (15761) SAIKI, M.K. &T.P. LOWE, 1987. Selenium (15763) ARNOLD, A., 1993. Die Libellen (Odonata) in aquatic organisms from subsurface agricultur- der “Papitzer Lehmlachen” im NSG Luppeaue bei al drainagewater, San JoaquinValley, California. Leipzig. Verbff. NaturkMus. Leipzig 11; 27-34. - Archs emir. Contam. Toxicol. 16: 657-670. — (US (Zur schonen Aussicht 25, D-04435 Schkeuditz). Fish & Wildl. Serv., Natn. Fisheries Contaminant The locality is situated 10km NW of the city centre Res. Cent., Field Res, Stn, 6924 Tremont Rd, Dixon, of Leipzig, E Germany (alt, 97 m). An annotated CA 95620, USA). list is presented of 30 spp., evidenced during 1985- Concentrations of total selenium were investigated -1993. in plant and animal samplesfrom Kesterson Reser- voir, receiving agricultural drainage water (Merced (15764) BEKUZIN, A.A., 1993. Otryad Strekozy - — Co.) and, as a reference, from the Volta Wildlife Odonatoptera(Odonata). [OrderDragonflies — km of which Area, ca 10 S Kesterson, has high qual- Odonatoptera(Odonata)].Insectsof Uzbekistan , pp. ity irrigationwater. Overall,selenium concentrations 19-22,Fan, Tashkent, (Russ.). - (Author’s address in samples from Kesterson averaged about 100-fold unknown). than those from Volta. in and A rather 20 of higher Thus, May general text, mentioning (out 76) spp. Aug. 1983, the concentrations (pg/g dry weight) at No locality data, but some notes on their habitats Kesterson in larval had of 160- and vertical in Central Asia. Zygoptera a range occurrence 220 and in Anisoptera 50-160. In Volta,these values were 1.2-2.I and 1.1-2.5, respectively. In compari- (15765) GAO, Zhaoning, 1993. -

(Tantilla Oolitica) in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties, Florida

Assessment of the Status and Distribution of the Endemic Rim Rock Crowned Snake (Tantilla oolitica) in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties, Florida Final Report Grant Agreement #401817G006 Kirsten N. Hines and Keith A. Bradley July 10, 2009 Submitted by: The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, FL 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to: Paula Halupa Fish and Wildlife Biologist U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1339 20th Street Vero Beach, FL 32960 1 Project Background: The rim rock crowned snake (Tantilla oolitica) is one of three species of small, burrowing snakes within the genus Tantilla found in Florida. Of the more than 40 species of this genus extending from the southeastern United States down to northern Argentina in South America, T. oolitica has the most limited distribution (Wilson 1982, Scott 2004). Confined to the Miami Rock Ridge in southeastern Miami-Dade County and parts of the Florida Keys in Monroe County, this species has been greatly affected by the rapid urbanization of this area. By 1975 it had already made the Florida State list of threatened species and it is currently considered a candidate for the Federal Endangered Species List. Traditionally, T. oolitica habitat included rockland hammocks and pine rocklands. Less than 2% of the pine rocklands on the Miami Rock Ridge currently remain (Snyder et. al 1990, USFWS 1999) and rockland hammocks both in Miami-Dade County and throughout the Florida Keys have been reduced to less than half their original extent and continue to face threat of development (Enge et. al 1997, USFWS 1999). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

John C. Abbott Director, Museum Research and Collections Alabama

John C. Abbott Director, Museum Research and Collections http://www.OdonataCentral.org Alabama Museum of Natural History http://www.MigratoryDragonflyPartnership.org The University of Alabama http://www.PondWatch.org 119 Smith Hall, Box #870340 http://www.AbbottNature.com Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0340 USA http://www.AbbottNaturePhotography.com http://almnh.ua.edua (205) 348-0534, office (512) 970-4090, cell [email protected]; [email protected] EDUCATION Stroud Water Research Center, Philadelphia Academy of Sciences Postdoc, 1999 University of North Texas Biology/Ecology Ph.D., 1999 University of North Texas Biology/Ecology M.S., 1998 Texas A&M University Zoology/Entomology B.S., 1993 Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science, University of North Texas 1991 PROFESIONAL EXPERIENCE 2016-present Director, Museum Research and Collections, University of Alabama Museums 2016-present Adjunct Faculty, Department of Anthropology, University of Alabama 2013-2015 Director, Wild Basin Creative Research Center at St. Edward’s University 2006-2013 Curator of Entomology, Texas Natural Science Center 2005-2013 Senior Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences, UT Austin 1999-2005 Lecturer, School of Biological Sciences, University of Texas at Austin 2004-2013 Environmental Science Institute, University of Texas 2000-2006 Research Associate, Texas Memorial Museum, Texas Natural History Collections 1999 Research Scientist, Stroud Water Research Center, Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences 1997-1998 Associate Faculty, Collin County Community College (Plano, Texas) 1997-1998 Teaching Fellow, University of North Texas PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS 27. J.C. Abbott. In prep. Description of the male and nymph of Phyllogomphoides cornutifrons (Odonata: Gomphidae): A South American enigma. 26. J.C. Abbott, K.K. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

A Checklist of North American Odonata, 2021 1 Each Species Entry in the Checklist Is a Paragraph In- Table 2

A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2021 Edition (updated 12 February 2021) A Checklist of North American Odonata Including English Name, Etymology, Type Locality, and Distribution 2021 Edition (updated 12 February 2021) Dennis R. Paulson1 and Sidney W. Dunkle2 Originally published as Occasional Paper No. 56, Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, June 1999; completely revised March 2009; updated February 2011, February 2012, October 2016, November 2018, and February 2021. Copyright © 2021 Dennis R. Paulson and Sidney W. Dunkle 2009, 2011, 2012, 2016, 2018, and 2021 editions published by Jim Johnson Cover photo: Male Calopteryx aequabilis, River Jewelwing, from Crab Creek, Grant County, Washington, 27 May 2020. Photo by Netta Smith. 1 1724 NE 98th Street, Seattle, WA 98115 2 8030 Lakeside Parkway, Apt. 8208, Tucson, AZ 85730 ABSTRACT The checklist includes all 471 species of North American Odonata (Canada and the continental United States) considered valid at this time. For each species the original citation, English name, type locality, etymology of both scientific and English names, and approximate distribution are given. Literature citations for original descriptions of all species are given in the appended list of references. INTRODUCTION We publish this as the most comprehensive checklist Table 1. The families of North American Odonata, of all of the North American Odonata. Muttkowski with number of species. (1910) and Needham and Heywood (1929) are long out of date. The Anisoptera and Zygoptera were cov- Family Genera Species ered by Needham, Westfall, and May (2014) and West- fall and May (2006), respectively. -

A Checklist of Oklahoma Odonata

Libellula comanche Calvert, 1907 - Comanche Skimmer Useful regional references: Libellula composita (Hagen, 1873) - Bleached Skimmer A Checklist of Libellula croceipennis Selys, 1868 - Neon Skimmer —Dragonflies and damselflies of the West by Dennis Paulson (2009) Libellula cyanea Fabricius, 1775 - Spangled Skimmer and Dragonflies and damselflies of the East by Dennis Paulson (2011) Oklahoma Odonata Libellula flavida Rambur, 1842 - Yellow-sided Skimmer Princeton University Press. Libellula incesta Hagen, 1861 - Slaty Skimmer —Damselflies of Texas: A Field Guide by John C. Abbott (2011) and (Dragonflies and Damselflies) Libellula luctuosa Burmeister, 1839 - Widow Skimmer Dragonflies of Texas: A Field Guide by John C. Abbott (2015) University of Texas Press. Libellula nodisticta Hagen, 1861 - Hoary Skimmer Libellula pulchella Drury, 1773 - Twelve-spotted Skimmer —Oklahoma Odonata Project: https://biosurvey.ou.edu/smith/Oklahoma_Odonata.html Libellula saturata Uhler, 1857 - Flame Skimmer Compiled by Brenda D. Smith — Smith BD, Patten MA (2020) Dragonflies at a Biogeographical Libellula semifasciata Burmeister, 1839 - Painted Skimmer Crossroads: The Odonata of Oklahoma and Complexities Beyond its & Michael A. Patten Libellula vibrans Fabricius, 1793 - Great Blue Skimmer Borders. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, USA. Macrodiplax balteata (Hagen, 1861) - Marl Pennant Miathyria marcella (Selys, 1856) - Hyacinth Glider Oklahoma Biological Survey, Micrathyria hagenii Kirby, 1890 - Thornbush Dasher Oklahoma -

Natural Resource Year in Review--2003

National Park Service National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Natural Resource Information Division Natural Resource Information Division in Review–2003 Year Natural Resource WASO-NRID P.O. Box 25287 Natural Resource Year in Review–2003 Denver, CO 80225-0287 A portrait of the year in natural resource stewardship and science in the National Park System ISSN 1544-5429 D-1533/March 2004 “Employees of the National Park Service are our best asset.” –Fran Mainella NPS Director Restoration Transforming The New Face Cooperative the National of Professional Conservation Park System Resource Management Inventory and Conserving Monitoring Threatened Charges Ahead and Endangered Species Preventing Natural Resource Impairment National Park Service / U.S. Department of the Interior Frontiers for Science and Natural Resource Education EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICATM Natural Resource Year in Review–2003 www.nature.nps.gov/YearInReview ISSN ı544-5429 “Despite changes in economic status, political upheaval, social injustices, Published by National Park Service Natural Resource The Year in Review is published or disasters, the national parks are always available to serve as actual National Park Service Director Program Center electronically on the World U.S. Department of the Interior Fran Mainella Chief, Air Resources Division Wide Web (ISSN ı544-5437) or potential refuges. The parks are traditionally ‘American,’ are always Natural Resource Information [email protected] Christine Shaver at www.nature.nps.gov/ welcoming, and serve as symbols of all that we value.” Division [email protected] YearInReview. Denver, Colorado, and Natural Resource Stewardship —Paul G. Risser Science and Ecosystem Management in the National Parks Washington, D.C. -

Overview Not Confine the Discussion in This Report to Those Specific Issues Within the Commission’S Regulatory Jurisdiction

television, cable and satellite media outlets operate. Accordingly, we do Overview not confine the discussion in this report to those specific issues within the Commission’s regulatory jurisdiction. Instead, we describe below 1 MG Siegler, Eric Schmidt: Every 2 Days We Create As Much Information a set of inter-related changes in the media landscape that provide the As We Did Up to 2003, TECH CRUNCH, Aug 4, 2010, http://techcrunch. background for future FCC decision-making, as well as assessments by com/2010/08/04/schmidt-data/. other policymakers beyond the FCC. 2 Company History, THomsoN REUTERS (Company History), http://thom- 10 Founders’ Constitution, James Madison, Report on the Virginia Resolu- sonreuters.com/about/company_history/#1890_1790 (last visited Feb. tions, http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendI_ 8, 2011). speechs24.html (last visited Feb. 7, 2011). 3 Company History. Reuter also used carrier pigeons to bridge the gap in 11 Advertising Expenditures, NEwspapER AssoC. OF AM. (last updated Mar. the telegraph line then existing between Aachen and Brussels. Reuters 2010), http://www.naa.org/TrendsandNumbers/Advertising-Expendi- Group PLC, http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/ tures.aspx. Reuters-Group-PLC-Company-History.html (last visited Feb. 8, 2011). 12 “Newspapers: News Investment” in PEW RESEARCH CTR.’S PRoj. foR 4 Reuters Group PLC (Reuters Group), http://www.fundinguniverse.com/ EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM, THE StatE OF THE NEws MEDIA 2010 (PEW, company-histories/Reuters-Group-PLC-Company-History.html (last StatE OF NEws MEDIA 2010), http://stateofthemedia.org/2010/newspa- visited Feb. 8, 2011). pers-summary-essay/news-investment/. -

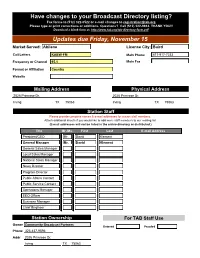

TAB Records-Stations (TABSERVER08)

Have changes to your Broadcast Directory listing? Fax forms to (512) 322-0522 or e-mail changes to [email protected] Please type or print corrections or additions. Questions? Call (512) 322-9944. THANK YOU!! Download a blank form at: http://www.tab.org/tab-directory-form.pdf Updates due Friday, November 15 Market Served: Abilene License City: Baird Call Letters KABW-FM Main Phone 817-917-7233 Frequency or Channel 95.1 Main Fax Format or Affiliation Country Website Mailing Address Physical Address 2026 Primrose Dr. 2026 Primrose Dr. Irving TX 75063 Irving TX 75063 Station Staff Please provide complete names & e-mail addresses for station staff members. Attach additional sheets if you would like to add more staff members to our mailing list. (E-mail addresses will not be listed in the online directory or distributed.) Title Mr./Ms. First Last E-mail Address President/CEO Mr. David Klement General Manager Mr. David Klement General Sales Manager Local Sales Manager National Sales Manager News Director Program Director Public Affairs Contact Public Service Contact Operations Manager EEO Officer Business Manager Chief Engineer Station Ownership For TAB Staff Use Owner Community Broadcast Partners Entered Proofed Phone 325-437-9596 Addr 2026 Primrose Dr. Irving TX 75063 Have changes to your Broadcast Directory listing? Fax forms to (512) 322-0522 or e-mail changes to [email protected] Please type or print corrections or additions. Questions? Call (512) 322-9944. THANK YOU!! Download a blank form at: http://www.tab.org/tab-directory-form.pdf Updates due Friday, November 15 Market Served: Abilene License City: Abilene Call Letters KACU-FM Main Phone 325-674-2441 Frequency or Channel 89.7 Main Fax 325-674-2417 Format or Affiliation Soft AC, News (NPR) Website www.kacu.org Mailing Address Physical Address ACU Station 1600 Campus Court Abilene TX 79699-7820 Abilene TX 79601 Station Staff Please provide complete names & e-mail addresses for station staff members. -

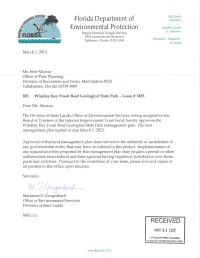

03.01.2012 WKFRGSP AP.Pdf

Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park APPROVED Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks March 1, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................1 PURPOSE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PARK .....................................................1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PLAN ......................................................................2 MANAGEMENT PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................................8 Management Authority and Responsibility ..............................................................8 Park Management Goals ..............................................................................................9 Management Coordination ........................................................................................10 Public Participation .....................................................................................................10 Other Designations ......................................................................................................10 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT COMPONENT INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................11 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION AND ASSESSMENT .................................................12 Natural Resources .......................................................................................................12 Topography