Lecture 06: Theta-Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Feature Clusters

Chapter 2 Feature Clusters 1. Introduction The goal of this Chapter is to address certain issues that pertain to the properties of feature clusters and the rules that govern their co-occurrences. Feature clusters come as fully specified (e.g. [+c+m] associated with people in (1a)) and ‘underspecified’ (e.g. [-c] associated with acquaintances in (1a)). Such partitioning of feature clusters raises the question of the implications of notions such as ‘underspecified’ and ‘fully specified’ in syntactic and semantic terms. The sharp contrast between the grammaticality of the middle derivation in (1b) and ungrammaticality of (1c) takes the investigation into rules that regulate the co-realization of feature clusters of the base-verb (1a). Another issue that is discussed in this Chapter is the status of arguments versus adjuncts in the Theta System. This topic is also of importance for tackling the issue of middles in Chapter 4 since – intriguingly enough – whereas (1c) is not an acceptable middle derivation in English, (1d) is. (1a) People[+c+m] don’t send expensive presents to acquaintances[-c] (1b) Expensive presents send easily. (1c) *Expensive presents send acquaintances easily. (1d) Expensive presents do not send easily to foreign countries. In section 2 of this Chapter, the properties of feature clusters with respect to syntax and semantics are examined. Section 3 sets the background for Section 4 by addressing the issue of conditions on thematic roles that have been assumed in the literature. Section 4 deals with conditions that govern the co-occurrences of feature clusters in the Theta System. The discussion in section 4 will necessitate the discussion of adjunct versus argument status of certain phrases. -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

1 the Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory

1 The Syntax of Scope Anna Szabolcsi January 1999 Submitted to Baltin—Collins, Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory 1. Introduction This chapter reviews some representative examples of scopal dependency and focuses on the issue of how the scope of quantifiers is determined. In particular, we will ask to what extent independently motivated syntactic considerations decide, delimit, or interact with scope interpretation. Many of the theories to be reviewed postulate a level of representation called Logical Form (LF). Originally, this level was invented for the purpose of determining quantifier scope. In current Minimalist theory, all output conditions (the theta-criterion, the case filter, subjacency, binding theory, etc.) are checked at LF. Thus, the study of LF is enormously broader than the study of the syntax of scope. The present chapter will not attempt to cover this broader topic. 1.1 Scope relations We are going to take the following definition as a point of departure: (1) The scope of an operator is the domain within which it has the ability to affect the interpretation of other expressions. Some uncontroversial examples of an operator having scope over an expression and affecting some aspect of its interpretation are as follows: Quantifier -- quantifier Quantifier -- pronoun Quantifier -- negative polarity item (NPI) Examples (2a,b) each have a reading on which every boy affects the interpretation of a planet by inducing referential variation: the planets can vary with the boys. In (2c), the teachers cannot vary with the boys. (2) a. Every boy named a planet. `for every boy, there is a possibly different planet that he named' b. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Principles and Parameters Set out from Europe

Principles and Parameters Set Out from Europe Mark Baker MIT Linguistics 50th Anniversary, 9 December 2011 1. The Opportunity Afforded (1980-1995) The conception of universal principles plus finite discrete parameters of variation offered: The hope and challenge of simultaneously doing justice to both the similarities and the differences among languages. The discovery and expectation of patterns in crosslinguistic variation. These were first presented with respect to “medium- sized” differences in European languages: The subjacency parameter (Rizzi, 1982) The pro-drop parameter (Chomsky, 1981; Kayne, 1984; Rizzi, 1982) They were then perhaps extended to the largest differences among languages around the world: The configurationality parameter(s) (Hale, 1983) “The more languages differ, the more they are the same” Example 1: Mohawk (Baker, 1988, 1991, 1996) Mohawk seems nonconfigurational, with no “syntactic” evidence of a VP containing the object and not the subject: (1) a. Sak wa-ha-hninu-’ ne ka-nakt-a’. Sak FACT-3mS-buy-PUNC NE 3n-bed-NSF b. Sak kanakta wahahninu’ c. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ ne Sak d. Kanakta’ Sak wahahninu’ e. Wahahninu’ ne Sak ne kanakta’ f. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ ne Sak g. Wahahninu’ ne kanakta’ h. Kanakta’ wahahninu’ i. Sak wahahninu’ j. Wahahninu’ ne Sak k. Wahahninu. All: ‘Sak/he bought a bed/it.’ There are also no differences between subject and object in binding (Condition C, neither c- commands the other) or wh-extraction (both are islands, no “subject condition”) (Baker 1992) Mohawk is polysynthetic (agreement, noun incorporation, applicative, causative, directionals…): (2) a. Sak wa-ha-nakt-a-hninu-’ Sak FACT-3mS-bed-Ø-buy-PUNC ‘Sak bought the bed.’ 1 b. -

Chapter 1 Basic Categorial Syntax

Hardegree, Compositional Semantics, Chapter 1 : Basic Categorial Syntax 1 of 27 Chapter 1 Basic Categorial Syntax 1. The Task of Grammar ............................................................................................................ 2 2. Artificial versus Natural Languages ....................................................................................... 2 3. Recursion ............................................................................................................................... 3 4. Category-Governed Grammars .............................................................................................. 3 5. Example Grammar – A Tiny Fragment of English ................................................................. 4 6. Type-Governed (Categorial) Grammars ................................................................................. 5 7. Recursive Definition of Types ............................................................................................... 7 8. Examples of Types................................................................................................................. 7 9. First Rule of Composition ...................................................................................................... 8 10. Examples of Type-Categorial Analysis .................................................................................. 8 11. Quantifiers and Quantifier-Phrases ...................................................................................... 10 12. Compound Nouns -

Intro to Linguistics – Syntax 1 Jirka Hana – November 7, 2011

Intro to Linguistics – Syntax 1 Jirka Hana – November 7, 2011 Overview of topics • What is Syntax? • Part of Speech • Phrases, Constituents & Phrase Structure Rules • Ambiguity • Characteristics of Phrase Structure Rules • Valency 1 What to remember and understand: Syntax, difference between syntax and semantics, open/closed class words, all word classes (and be able to distinguish them based on morphology and syntax) Subject, object, case, agreement. 1 What is Syntax? Syntax – the part of linguistics that studies sentence structure: • word order: I want these books. *want these I books. • agreement – subject and verb, determiner and noun, . often must agree: He wants this book. *He want this book. I want these books. *I want this books. • How many complements, which prepositions and forms (cases): I give Mary a book. *I see Mary a book. I see her. *I see she. • hierarchical structure – what modifies what We need more (intelligent leaders). (more of intelligent leaders) We need (more intelligent) leaders. (leaders that are more intelligent) • etc. Syntax is not about meaning! Sentences can have no sense and still be grammatically correct: Colorless green ideas sleep furiously. – nonsense, but grammatically correct *Sleep ideas colorless furiously green. – grammatically incorrect Syntax: From Greek syntaxis from syn (together) + taxis (arrangement). Cf. symphony, synonym, synthesis; taxonomy, tactics 1 2 Parts of Speech • Words in a language behave differently from each other. • But not each word is entirely different from all other words in that language. ⇒ Words can be categorized into parts of speech (lexical categories, word classes) based on their morphological, syntactic and semantic properties. Note that there is a certain amount of arbitrariness in any such classification. -

The Syntax of Word Order Derivation and Agreement in Najrani Arabic: a Minimalist Analysis

English Language Teaching; Vol. 10, No. 2; 2017 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Syntax of Word Order Derivation and Agreement in Najrani Arabic: A Minimalist Analysis Abdul-Hafeed Ali Fakih1 & Hadeel Ali Al-Sharif2 1 Department of English, University of Ibb, Yemen & Department of English, University of Najran, Saudi Arabia 2 Department of English, University of Najran, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Abdul-Hafeed Ali Fakih, Department of English, University of Najran, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 1, 2016 Accepted: January 7, 2017 Online Published: January 9, 2017 doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n2p48 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n2p48 Abstract The paper aims to explore word order derivation and agreement in Najran Arabic (henceforth, NA) and examines the interaction between the NA data and Chomsky’s (2001, 2005) Agree theory which we adopt in this study. The objective is to investigate how word order occurs in NA and provide a satisfactorily unified account of the derivation of SVO and VSO orders and agreement in the language. Furthermore, the study shows how SVO and VSO word orders are derived morpho-syntactically in NA syntax and why and how the derivation of SVO word order comes after that of VSO order. We assume that the derivation of the unmarked SVO in NA takes place after applying a further step to the marked VSO. We propose that the default unmarked word order in NA is SVO, not VSO. Moreover, we propose that the DP which is base-generated in [Spec-vP] is a topic, not a subject. -

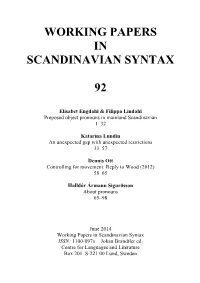

Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 92 (2014) 1–32 ! 2

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINAVIAN SYNTAX 92 Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian 1–32 Katarina Lundin An unexpected gap with unexpected restrictions 33–57 Dennis Ott Controlling for movement: Reply to Wood (2012) 58–65 Halldór Ármann Sigur!sson About pronouns 65–98 June 2014 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax ISSN: 1100-097x Johan Brandtler ed. Centre for Languages and Literature Box 201 S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Preface: Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax is an electronic publication for current articles relating to the study of Scandinavian syntax. The articles appearing herein are previously unpublished reports of ongoing research activities and may subsequently appear, revised or unrevised, in other publications. The WPSS homepage: http://project.sol.lu.se/grimm/working-papers-in-scandinavian-syntax/ The 93rd volume of WPSS will be published in December 2014. Papers intended for publication should be submitted no later than October 15, 2014. Contact: Johan Brandtler, editor [email protected]! Preposed object pronouns in mainland Scandinavian* Elisabet Engdahl & Filippa Lindahl University of Gothenburg Abstract We report on a study of preposed object pronouns using the Scandinavian Dialect Corpus. In other Germanic languages, e.g. Dutch and German, preposing of un- stressed object pronouns is restricted, compared with subject pronouns. In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, we find several examples of preposed pronouns, ranging from completely unstressed to emphatically stressed pronouns. We have investi- gated the type of relation between the anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent and found that the most common pattern is rheme-topic chaining followed by topic- topic chaining and left dislocation with preposing. -

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure

Handout 1: Basic Notions in Argument Structure Seminar The verb phrase and the syntax-semantics interface , Andrew McIntyre 1 Introduction 1.1 Some basic concepts Part of the knowledge we have about certain linguistic expressions is that they must or may appear with certain other expressions (their arguments ) in order to be interpreted semantically and in order to produce a syntactically well-formed phrase/sentence. (1) John put the book near the door put takes John, the book and near the door as arguments near takes the door and arguably the book as arguments (2) Fred’s reliance on Mary reliance takes on Mary and Fred as arguments (3) John is fond of his stamp collection fond takes his stamp collection and John as arguments An expression taking an argument is called a predicate in modern & philosophical terminology (distinguish from old terminology where predicate = verb phrase). An argument can itself be a predicate (4) Gertrude got angry (in some theories, angry is an argument of get , and Gertrude is an argument of both get and angry ) Some linguists say that arguments can be shared by two predicates, e.g. in (1) the book might be taken to be an argument of both put and near . Argument structure (valency) : the (study of) the arguments taken by expressions. In syntax, we say a predicate (e.g. a verb) has, takes, subcategorises for, selects this or that (or so-and-so many) argument(s). You cannot say you know a word unless you know its argument structure. A word’s argument structure must be mentioned in its lexical entry (=the information associated with the word in the mental lexicon , i.e.