JASO-Online Volume I, Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Household Survey Mardan 2010

Baseline Household Survey Mardan District May 2010 4t Population Council Family Advancement for Life and Health (FALAH) Mardan Baseline Household Survey May 2010 Dr. Yasir Bin Nisar Irfan Masood The Population Council, an international, non‐profit, non‐governmental organization established in 1952, seeks to improve the well‐being and reproductive health of current and future generations around the world and to help achieve a humane, equitable, and sustainable balance between people and resources. The Council analyzes population issues and trends; conducts research in the reproductive sciences; develops new contraceptives; works with public and private agencies to improve the quality and outreach of family planning and reproductive health services; helps governments design and implement effective population policies; communicates the results of research in the population field to diverse audiences; and helps strengthen professional resources in developing countries through collaborative research and programs, technical exchange, awards, and fellowships. The Population Council reserves all rights of ownership of this document. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form by any means‐electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise‐without the permission of the Population Council. For inquiries, please contact: Population Council # 7, Street 62, F‐6/3, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: 92 51 8445566 Fax: 92 51 2821401 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.popcouncil.org http://www.falah.org.pk Layout and Design: Ali Ammad Published: May 2010 Disclaimer “This study/report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the Population Council, Islamabad and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.” ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ -

Pdf | 398.65 Kb

Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report (WMMR) IDP Hosting Districts, NWFP, Pakistan Week # 27 (27 Jun – 3 July), 2009 Emergency Humanitarian Action (EHA) Islamabad, Pakistan Children with Leishmaniasis attended for treatment in Jalozai II, IDP camp (Picture by WHO Team) Highlights: • Two alerts of AWD cases received (one from district Mardan and another from IDP camp Palosa‐II, district Charrsada) were investigated and identified as severe acute diarrhoea. • During this week, 198 health facilities reported 67430 patients’ consultations through the DEWS network • Acute Diarrhoea was reported in 8% (5682) of the total consultations in all age groups, while it accounts for 15% of consultations in children <5 years of age and 7% of the consultations in the patients above 5 years age • Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) continues to be the leading cause of morbidity, with a total of 14036 consultations (21% of total consultations) in IDP hosting districts NWFP. • In children less than 5 years of age, ARI accounts for 4129 (28%) of the total consultations. The WMMR is published by the World Health Organization (WHO), Emergency Humanitarian Action (EHA) unit, National Park Road, Chak Shahzad, Islamabad, Pakistan. For More Information, please contact: Dr. Ahmed Farah Shadoul , Chief of Operations, EHA , WHO, Pakistan; [email protected] Dr. Fazal Qayyum, Director Health Services, Department of Health NWFP, Pakistan Dr. Musa Rahim Khan, Senior Public Health Officer (DEWS Coordinator), WHO,EHA , Pakistan; [email protected] 1. Alert & outbreak investigations and response: During the epidemiological week 27 of 2009, two alerts of acute watery diarrhoea (AWD) were reported and DEWS teams investigated the alerts and identified as cases of acute diarrhoea. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Baseline Study for SWM in Mardan Pakistan

Baseline Study for SWM in Mardan Pakistan September 2012 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................ 6 1.1. Background ....................................................................................... 6 1.2. Objectives ........................................................................................ 6 1.3. Study Design and Methodology................................................................. 6 2. Scope ................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Geographical Scope of Study ................................................................... 8 2.2. Mardan ............................................................................................ 8 2.3. City Statistics..................................................................................... 8 2.4. Guli Bagh (The Study Area)..................................................................... 9 3. The State of Waste in Mardan ..................................................................... 11 3.1. Situation in the City ........................................................................... 11 3.2. City Waste Composition and total waste generated ...................................... 11 2 3.3. Differentiate between categories of Solid Waste .......................................... 11 3.4. Hospital waste management ................................................................. 11 -

Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

55 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Contents Introduction 56 Aims and Objectives of the Survey 56 Geography and Land Economy 57 Historical and Archaeological Perspective 58 Early Surveys, Explorations and Excavations 60 List of Protected Sites and Monuments 61 Inventory of Archaeological Sites Recorded in the Current Survey 62 Analysis of Archaeological Data from the Surface Collection 98 Small Finds 121 Conclusion 126 Sites Recommended for Excavation, Conservation and Protection 128 List of Historic I Settlement Sites 130 Acknowledgements 134 Notes 134 Bibliographic References 135 Map 136 Figures 137 Plates 160 56 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Introduction The Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, (hereafter the Department) in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, (hereafter the Federal Department) initiated a project of surveying and documenting archaeological sites and historical monuments in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). The primary objectives of the project were to formulate plans for future research, highlight and project the cultural heritage of the Province and to promote cultural tourism for sustainable development. The Department started the project in 1993 and since then has published two survey reports of the Charsadda and Swabi Districts. 1 Dr. Abdur Rahman conducted survey of the Peshawar and Nowshera Districts and he will publish the report after analysis of the data. 2 Conducted by the present author, the current report is focussed on the archaeological survey of the Mardan District, also referred to as the Yusafzai Plain or District. -

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia Jonathan Mark KenoyerAccess Felicitation Volume Open Edited by Dennys Frenez, Gregg M. Jamison, Randall W. Law, Massimo Vidale and Richard H. Meadow Archaeopress Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 917 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 918 4 (e-Pdf) © ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente, Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Front cover: SEM microphotograph of Indus unicorn seal H95-2491 from Harappa (photograph by J. Mark Kenoyer © Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Access Back cover, background: Pot from the Cemetery H Culture levels of Harappa with a hoard of beads and decorative objects (photograph by Toshihiko Kakima © Prof. Hideo Kondo and NHK promotions). Back cover, box: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer excavating a unicorn seal found at Harappa (© Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Open ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 244 Palazzo Baleani Archaeopress Roma, RM 00186 www.ismeo.eu Serie Orientale Roma, 15 This volume was published with the financial assistance of a grant from the Progetto MIUR 'Studi e ricerche sulle culture dell’Asia e dell’Africa: tradizione e continuità, rivitalizzazione e divulgazione' All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by The Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. -

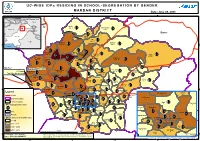

UC-WISE Idps RESIDING in SCHOOL-SEGREGATION BY

FANA U C - W I S E I D P s R E S I D I N G I N S C H O O L - S E G R E G AT I O N B Y G E N D E R UNOCHA M A R D A N D I S T R I C T Date :June 08, 2009 71°50'E 72°E 72°10'E 72°20'E Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Uzbekistan IDPs Intervention Area Tajikistan China Turkmenistan Pakistan Aksai Chin Kharki Jammu Kashmir ´ 406 ,6 Kohi Bermol Afghanistan 114 ,5 MalakCahina/dInd iPa A Buner PAKISTAN Qasmi Nepal 680 ,14 Iran Alo India 964 ,20 N N " Mian Issa Babozai " 0 0 3 3 ' ' 5 1638 ,40 222 ,8 5 2 2 ° ° 4 4 3 Arabian Sea 3 Shergarh Makori 959 ,19 Dherai Likpani 1028 ,16 Shamozai Bazar 1553 ,41 848 ,20 Lund Khawar 663 ,13 Hathian Pir Saddo 2911 ,41 Katlang-1 Palo Dheri 1631 ,21 Jalala 2760 ,18 Kati Garhi 928 ,15 1020 ,18 1741 ,16 572 ,15 Rustam 489 ,8 Katlang-2 Map Key: Takht Bhai 486 ,17 Mardan Kata Khat Parkho Dherai Jamal Garhi Chargalli UC Name Madey Baba 368 ,14 1927 ,35 183 ,6 383 ,11 1520 ,27 Sawal Dher Total IDPs, No of School 546 ,13 Daman-e-Koh Takkar 1317 ,5 1407 ,11 Kot Jungarah Mardan 2003 ,21 Machi Fathma Bakhshali Gujrat 91 ,4 Pat Baba 716 ,15 449 ,9 469 ,6 Narai 803 ,11 Garyala 948 ,21 Bala Garhi 711 ,15 Seri Bahlol 447 ,14 N N ' 1194 ,20 ' 5 Babini 5 1 Jehangir Abad 1 ° ° 4 Saro Shah 4 3 1092 ,11 725 ,10 Shahbaz Garhi 3 1139 ,16 Legend 340 ,12 Gujar Garhi Jehangir Abad Babini 1237 ,9 Mohib Banda 11 10 Roads Charsadda BaghdadaDagai Chak Hoti Baghicha Dheri 1451 ,11 707 ,16 528 ,8 156 ,4 212 ,5 Garhi Daulatzai Gujar Garhi District Boundary Mardan Rural 9 252 ,6 493 ,6 Chamtar Tehsil Boundary Dagai 267 ,8 Par Hoti Chak Hoti Khazana Dheri -

Pakistan: Flash Floods in Swabi and Mardan District- North West Frontier Province

Pakistan: Flash floods in Swabi and Mardan District- North West Frontier Province Turkmenistan Tajikistan Tajikistan China Lower Dir Puran F.A.N.A. Swat Swat Martoong N.W.F.P. Aksai Chin P.A.K. Shangla Afghanistan Disputed Area Swat Rani Zai F.A . T. A . China/India China Malakand PA PUNJAB Mansehra Baizo Kharki Mardan BALOCHISTAN Kohi Barmol Ikram Pura Biazo Kharki Iran (Islamic Republic of) India Sam Rani Zai SINDH Qasmi Mian Khan Daggar Buner Miangano Killi Alo Mansehra Babuzai Shamozai Babuzai Mian Issa Dheri Lakpani Shergarh Lund Khwar v Lund Khwar Lund Khwar The following are he worst affected Union councils Aman Kot Hathian having approximately 500 houses damaged affecting Zor Abad Palo Dheri Rustam 35,000 people: Katlang Palo Dheri Kati Garhi Jalala v Tangi Pir Saddo Rustam Ghazi Takht Bhai Jamal Garhi Ismaila in Swabi district Pir Saddo Kata Khat Char Guli NARANJI Machi Garyala and Shahbaz Garhi in Mardan district Ta kht Bha i Mardan Haripur Kot Jungara BAHADAR ABAD(PARMOLI) Mian Killi Takkar Akbar Abad Parkho Dheri Less affected Union councils are as follows: Sawal Dher Gujrat Mardan Khair Abad Mardan Bakhshali Kalo khan, Adena in Swabi district Kodinaka Fathma UTLA GANI KOT Seri Behlol Galyara Mohib banda, Bala garhi in Mardan district Jamra Garyala !( !( GANI CHATRA GABASANI FS Mill Takht Bhai SHEWA SHEWA Bala Garhi !( Charbanda Shahbaz Garhi CHANAI Shahbaz Garhi ISMAILA !( Gujar garhi Adena SHEIKH JANA Baghicha Dheri Kalo Khan MANGOLCHAI ADINA Check Mardan NAWAN KILLI Kass Korona KALU KHAN TURLANDl !( Bughdada Mohib Banda -

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN Bulletin 9 PAKISTAN 19 August 2009

Conflict-Displaced Persons Crisis HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN Bulletin 9 PAKISTAN 19 August 2009 Highlights • 218 452 IDP families have now retur- ned to their homes and villages in Malakand Division. Another 15 564 families from Malakand Division remain scattered in camps and other locations in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Five new camps have been opened in Buner and Lower Dir. The Suwari and Karapa camps are currently hosting 889 families, while another 2,150 families have been registered at the Munda, Wali Kundo and Khungi Shah camps. J.G. Brouwer/WHO • Outpatient consultations for maternal, WHO staff teaches IDPs in Jalozai camp on how to treat water. neonatal and child health care have decreased by 8% in 7 maternal neonatal and child health care service delivery points in Lower Dir, Mardan and Nowshehra.However, At the same time, pre- and postnatal consultations have increased by 37% and 33% respectively. • WHO environmental health engineers are continuing to monitor water and sanitation in all IDP camps as well as in all host communities reporting a waterborne disease alert or outbreak. A total of 33 water samples were tested for biological contamination, and another 40 samples were tested for residual chlorine and over one fifth were found unfit for drinking. Water test results were forwarded to the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) cluster for appropriate actions. • Additional maternal, newborn and child health care services are badly needed in returnee districts to handle the increasing number of patients. Securing the services of trained female health care providers is a challenge given the precarious state of security. -

MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN Draft Final Report Draft Final Report

KP-SISUG Sector Road Map – Draft Final Report Pakistan: Provincial Strategy for Inclusive and Sustainable Urban Growth in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN Draft Final Report Draft Final Report January 2019 February 2019 KP-SISUG Mardan City Development Plan – Draft Final Report CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 January 2019) Currency unit – Pakistan Rupee (PKR) PKR1.00 = $0.0072 $1.00 = PKRs 138.85 ABBREVIATIONS ADA - Abbottabad Development Authority ADB - Asian Development Bank ADP - annual development program AP - action plan BOQ - bills of quantities BTE - Board of Technical Education CAD - computerized aided design CBT - competency based training CDIA - Cities Development Initiative for Asia CDP - city development plan CES - community entrepreneurial skills CIU - city implementation unit CMST - community management skills training CNC - computer numerical control CNG - compressed natural gas CPEC - China-Pakistan Economic Corridor CRVA - climate resilience and vulnerability assessment DAO - District Accounts Office DDAC - District Development Advisory Committee DFID - Department for International Development (UK) DFR - draft final report DM - disaster management DRR - disaster risk reduction EA - executing agency EFI - electronic fuel injection EIA - environmental impact assessment EMP - environmental management plan EPA - Environmental Protection Agency [of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] ESMS - environmental and social management system FATA - Federally Administered Tribal Area i KP-SISUG Mardan City -

SDF Annual Report 2004-05

1 Salik Development Foundation, Annual Report 2004-05 Salik Development Foundation Annual Report, 2004-05 2 Salik Development Foundation, Annual Report 2004-05 Table of Contents 1. List of Abbreviations 2. Board of Directors & G.Body Members 3. SDF Structure 4. Organogram 5. Detail of Staff 6. Pictures of various activities 7. Comparison pictures of CPI schemes 8. Community Physical Infrastructure (CPI) and 9. Water Supply & Sanitation 10. Irrigation 11. Health Program 12. Education Program 13. Environmental Protection 14. Advocacy 15. SDF Donors and Partners 16. Publications 17. Auditor’s Reports 18. Financial Statement 3 Salik Development Foundation, Annual Report 2004-05 List of Abbreviation 1. SDF Salik Development Foundation 2. PPAF Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund 3. CPI Community Physical Infrastructure 4. PHC Primary Health Care 5. MH Maternal Health 6. MMR Maternal Mortality Rate 7. MMR Maternal Morbidity Rate 8. IMR Infant Mortality Rate 9. BBCM Broad Based Community Meeting 10. TMA Tehsil Municipal Administration 11. TVO Trust for Voluntary Organization 12. RHC Rural Health Center 13. CH Civil Hospital 14. CO Community Organization 15. PAC Project Approval Committee 16. AKWS Al-Khidmat Welfare Society 17. AKTGS Awami Khidmat Gar Tanzeem Garo Shah 18. TBA Traditional Birth Attendant 19. SDCC Social Development Coordination Council 20 ANC Antenatal Check up 21. NCHD National Commission for Human Development 4 Salik Development Foundation, Annual Report 2004-05 Structure Board of Directors General Body Members Board of Directors President Secretary Executive Director Staff members. SDF Goal TO WORK FOR THE ESTABLISHMENTOF A PEACEFUL, PROSPEROUS AND DEVELOPED SOCIETY SDF Objectives • Conservation and Protection of Environment for sustainable development and sustainable utilization of Natural Resources. -

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils Alongwith Seats Detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

1 Annexure - D Names of Village / Neighbourhood Councils alongwith seats detail of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa No. of General Seats in No. of Seats in VC/NC (Categories) Names of S. Names of Tehsil Councils No falling in each Neighbourhood Village N/Hood Total Col Peasants/Work S. No. Village Councils (VC) S. No. Women Youth Minority . district Council Councils (NC) Councils Councils 7+8 ers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Abbottabad District Council 1 1 Dalola-I 1 Malik Pura Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 2 Dalola-II 2 Malik Pura Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 3 Dabban-I 3 Malik Pura Urban-III 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 4 Dabban-II 4 Central Urban-I 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 5 Boi-I 5 Central Urban-II 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 6 Boi-II 6 Central Urban-III 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 7 Sambli Dheri 7 Khola Kehal 7 7 14 4 2 2 2 8 Bandi Pahar 8 Upper Kehal 5 7 12 4 2 2 2 9 Upper Kukmang 9 Kehal 5 8 13 4 2 2 2 10 Central Kukmang 10 Nawa Sher Urban 5 10 15 4 2 2 2 11 Kukmang 11 Nawansher Dhodial 6 10 16 4 2 2 2 12 Pattan Khurd 5 5 2 1 1 1 13 Nambal-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 14 Nambal-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 Abbottabad 15 Majuhan-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 16 Majuhan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 17 Pattan Kalan-I 5 5 2 1 1 1 18 Pattan Kalan-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 19 Pattan Kalan-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 20 Sialkot 6 6 2 1 1 1 21 Bandi Chamiali 6 6 2 1 1 1 22 Bakot-I 7 7 2 1 1 1 23 Bakot-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 24 Bakot-III 6 6 2 1 1 1 25 Moolia-I 6 6 2 1 1 1 26 Moolia-II 6 6 2 1 1 1 1 Abbottabad No.