Determinants of Consanguinity and Inbreeding Coefficient in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Household Survey Mardan 2010

Baseline Household Survey Mardan District May 2010 4t Population Council Family Advancement for Life and Health (FALAH) Mardan Baseline Household Survey May 2010 Dr. Yasir Bin Nisar Irfan Masood The Population Council, an international, non‐profit, non‐governmental organization established in 1952, seeks to improve the well‐being and reproductive health of current and future generations around the world and to help achieve a humane, equitable, and sustainable balance between people and resources. The Council analyzes population issues and trends; conducts research in the reproductive sciences; develops new contraceptives; works with public and private agencies to improve the quality and outreach of family planning and reproductive health services; helps governments design and implement effective population policies; communicates the results of research in the population field to diverse audiences; and helps strengthen professional resources in developing countries through collaborative research and programs, technical exchange, awards, and fellowships. The Population Council reserves all rights of ownership of this document. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form by any means‐electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise‐without the permission of the Population Council. For inquiries, please contact: Population Council # 7, Street 62, F‐6/3, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: 92 51 8445566 Fax: 92 51 2821401 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.popcouncil.org http://www.falah.org.pk Layout and Design: Ali Ammad Published: May 2010 Disclaimer “This study/report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the Population Council, Islamabad and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.” ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Pakistan in Areas

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CONFLICT-AFFECTED POPULATIONS IN PAKISTAN IN FY 2009 AND TO DATE IN FY 2010 Faizabad KEY TAJIKISTAN USAID/OFDA USAID/Pakistan USDA USAID/FFP State/PRM DoD Amu darya AAgriculture and Food Security S Livelihood Recovery PAKISTAN Assistance to Conflict-Affected y Local Food Purchase Populations ELogistics Economic Recovery ChitralChitral Kunar Nutrition Cand Market Systems F Protection r Education G ve Gilgit V ri l Risk Reduction a r Emergency Relief Supplies it a h Shelter and Settlements C e Food For Progress I Title II Food Assistance Shunji gol DHealth Gilgit Humanitarian Coordination JWater, Sanitation, and Hygiene B and Information Management 12/04/09 Indus FAFA N A NWFPNWFP Chilas NWFP AND FATA SEE INSET UpperUpper DirDir SwatSwat U.N. Agencies, E KohistanKohistan Mahmud-e B y Da Raqi NGOs AGCJI F Asadabad Charikar WFP Saidu KUNARKUNAR LowerLower ShanglaShangla BatagramBatagram GoP, NGOs, BajaurBajaur AgencyAgency DirDir Mingora l y VIJaKunar tro Con ImplementingMehtarlam Partners of ne CS A MalakandMalakand PaPa Li Î! MohmandMohmand Kabul Daggar MansehraMansehra UNHCR, ICRC Jalalabad AgencyAgency BunerBuner Ghalanai MardanMardan INDIA GoP e Cha Muzaffarabad Tithwal rsa Mardan dd GoP a a PeshawarPeshawar SwabiSwabi AbbottabadAbbottabad y enc Peshawar Ag Jamrud NowsheraNowshera HaripurHaripur AJKAJK Parachinar ber Khy Attock Punch Sadda OrakzaiOrakzai TribalTribal AreaArea Î! Adj.Adj. PeshawarPeshawar KurrumKurrum AgencyAgency Islamabad Gardez TribalTribal AreaArea AgencyAgency Kohat Adj.Adj. KohatKohat Rawalpindi HanguHangu Kotli AFGHANISTAN KohatKohat ISLAMABADISLAMABAD Thal Mangla reservoir TribalTribal AreaArea AdjacentAdjacent KarakKarak FATAFATA BannuBannu us Bannu Ind " WFP Humanitarian Hub NorthNorth WWaziristanaziristan BannuBannu SOURCE: WFP, 11/30/09 Bhimbar AgencyAgency SwatSwat" TribalTribal AreaArea " Adj.Adj. -

Pdf | 398.65 Kb

Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report (WMMR) IDP Hosting Districts, NWFP, Pakistan Week # 27 (27 Jun – 3 July), 2009 Emergency Humanitarian Action (EHA) Islamabad, Pakistan Children with Leishmaniasis attended for treatment in Jalozai II, IDP camp (Picture by WHO Team) Highlights: • Two alerts of AWD cases received (one from district Mardan and another from IDP camp Palosa‐II, district Charrsada) were investigated and identified as severe acute diarrhoea. • During this week, 198 health facilities reported 67430 patients’ consultations through the DEWS network • Acute Diarrhoea was reported in 8% (5682) of the total consultations in all age groups, while it accounts for 15% of consultations in children <5 years of age and 7% of the consultations in the patients above 5 years age • Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) continues to be the leading cause of morbidity, with a total of 14036 consultations (21% of total consultations) in IDP hosting districts NWFP. • In children less than 5 years of age, ARI accounts for 4129 (28%) of the total consultations. The WMMR is published by the World Health Organization (WHO), Emergency Humanitarian Action (EHA) unit, National Park Road, Chak Shahzad, Islamabad, Pakistan. For More Information, please contact: Dr. Ahmed Farah Shadoul , Chief of Operations, EHA , WHO, Pakistan; [email protected] Dr. Fazal Qayyum, Director Health Services, Department of Health NWFP, Pakistan Dr. Musa Rahim Khan, Senior Public Health Officer (DEWS Coordinator), WHO,EHA , Pakistan; [email protected] 1. Alert & outbreak investigations and response: During the epidemiological week 27 of 2009, two alerts of acute watery diarrhoea (AWD) were reported and DEWS teams investigated the alerts and identified as cases of acute diarrhoea. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Kpk Police Complaint Cell

Kpk Police Complaint Cell Thysanuran Teador sometimes haul any portents dilutes sarcastically. Bigger Winny retches no neophytes evaluate dash after Reggy bespeaks aport, quite cadential. Jule is self-created: she enwinding queerly and char her dinosaurs. In online registration of a complaint saving them the labor of travel to bolster police. There will review security concerns, kpk police complaint cell will support me the police department to do not solved and arresting him in order situation in the systemic culture of pakistan. Senior officials are various levels also recognized the students of its content received from the khyber pakhtunkhwa at the local officials to the government agriculture policies. Maharashtra state police complaints cell for policing a genuine issues or the kpk can ask to review police? Channai, UC City No. Demand police said they saw their cell where law school at kpk police complaint cell for news? The police email, providing complainants confidential information from your complaint lodged a post to fight against us? Police complaint or complaint police followed them to the highway department which we immediately be. Updates about police complaint cell was also kpk it is, supported by human rights. Sanaullah Abbasi met on a delegation of Peshawar traders. Bilal in police were after being arrested for political reasons. KPK Police Online FIR Complaint System by SMS Fax Email Website Government of Khyber PakhtunKhwa has worse to KPK public and is facilitate them especially police. Case No کیس نمبر cannot enter blank. Take notice manshera girl feels that kpk police complaint cell number at kpk. -

Pdf | 497.71 Kb

LOWER INITIAL DAMAGE ASSESSMENT FOR DIR MONSOON FLOOD - 2010 SWAT BAJAUR C h i n a Malakand FANA KHYBER BUNER PAKHTUNKHWA MALAKAND Dargai Afghanistan FATA Kharki Kohi Bermol Qasmi PUNJAB Alo MOHMAND Mian Issa Babozai BALOCHISTAN Koz Behram Dheri II n n d d i i a a Shergarh Makori II r r a a n n Dherai Likpani Shamozai Bazar Hathian SINDH Lund Khawar Show Dag Gandera Hari Chand Palo Dheri Katlang-1 Pir Saddo Jalala Kati Garhi Sawal Dher 1 Parkho Arabian Sea Mandani Dherai Katlang-2 Ghalanai Abazai Rustam Sawal Dher 2 Kata Khat Hisara Nehri Madey Baba Tangi Jamal Garhi MARDAN Chargalli Legend Katuzai Takkar Kot Jungarah Dakki Machi Matta Gujrat Daman-e-koh Fathma Bakhshali WFP Assisted Camp Affected HH (%) Mughal CHARSADA Ziam Khel Sher Pao Narai Pat Baba Garyala Humanitarian Hub 7% - 15% Chindro Dag Seri Bahlol Bala Mirzadher Jehangir Abad Garhi Mira Umarzai Behlola Babini Shahbaz Garhi Early Recovery Delivery Point 16% - 30% Hassan Saro Shah Panjpad Batgram Umar Zai Sarki Titara Gujar Garhi Sange Zai Marmar Baghicha Mohib CP Distribution Point 31% - 60% Tarnab Khan Mahi Baghdada Kot Daulatzai Dheri Shabqadar Turang Zai Muhammad Chamtar Par Hoti Banda Kangra Daulatpura Nari Khazana Mardan Sikandari Koroona Humanitarian Logistics Base 61% - 80% Rashkai Mardan Rural Garhi Daulatzai Utmanzai Manga Dheri Bijli Ghar Bari Cham Chak Hoti Hissara Razar-II Muslimabad Dargai Hoti Garhi Ismailzai Major Town 81% - 100% Jogani Yasinzai Bagh-e-iram Haji Zai Mayar Razar-I Ghunda Rorya Shamatpur Karkana Guli Bagh Highway UC Boundary Anam Khatki Charsadda -

Baseline Study for SWM in Mardan Pakistan

Baseline Study for SWM in Mardan Pakistan September 2012 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................ 6 1.1. Background ....................................................................................... 6 1.2. Objectives ........................................................................................ 6 1.3. Study Design and Methodology................................................................. 6 2. Scope ................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Geographical Scope of Study ................................................................... 8 2.2. Mardan ............................................................................................ 8 2.3. City Statistics..................................................................................... 8 2.4. Guli Bagh (The Study Area)..................................................................... 9 3. The State of Waste in Mardan ..................................................................... 11 3.1. Situation in the City ........................................................................... 11 3.2. City Waste Composition and total waste generated ...................................... 11 2 3.3. Differentiate between categories of Solid Waste .......................................... 11 3.4. Hospital waste management ................................................................. 11 -

Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade Wise Marks 1St Div: 2Nd Div: 3Rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1

At least 2nd Division Master in Social Sciences (Social Work/ Sociology will be preferred) District: Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade wise marks 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks 60 S.S.C 15 11 9 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) 10 F.A/FSc 15 11 9 SOCIAL CASE WORKER (BPS-16) 3. Experience Certificate 15 BA/BSc 15 11 9 4. Interviews Marks 8 MA/MSc 15 11 9 5. Professional Training Marks 7 Total;- 60 44 36 Total;- 100 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF SOCIAL CASE WORKER BPS-16 BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC BA/BSc M.A/ MS.c S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # Appli: Remarks Domicile Malrks= 7 Total Marks Marks Marks Marks Marks Date of Birth Qualification Division Division Division Division Marks P.HD Marks M.Phil Marks of Experience Professional/Training One Stage Above 7 Two Two Stage Above 10 Interview Marks 8 Marks Year of Experience 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Mr. Farhan Raza S/O Abid Raza, Koz Kaly Madyan, P.O Madyan, Tehsil and District Swat, 0314- Mphil Agriculture Rual 71 3/2/1992 Swat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 9818407 Sociology Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan S/O Muhammad Naeem Khan, Rahat Abad Colony, Bannu Road P.O PHD Business 494 16-04-1990 Lakki Marwat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 Sheikh Yousaf District D.I.Khan. -

Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

55 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Contents Introduction 56 Aims and Objectives of the Survey 56 Geography and Land Economy 57 Historical and Archaeological Perspective 58 Early Surveys, Explorations and Excavations 60 List of Protected Sites and Monuments 61 Inventory of Archaeological Sites Recorded in the Current Survey 62 Analysis of Archaeological Data from the Surface Collection 98 Small Finds 121 Conclusion 126 Sites Recommended for Excavation, Conservation and Protection 128 List of Historic I Settlement Sites 130 Acknowledgements 134 Notes 134 Bibliographic References 135 Map 136 Figures 137 Plates 160 56 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Introduction The Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, (hereafter the Department) in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, (hereafter the Federal Department) initiated a project of surveying and documenting archaeological sites and historical monuments in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). The primary objectives of the project were to formulate plans for future research, highlight and project the cultural heritage of the Province and to promote cultural tourism for sustainable development. The Department started the project in 1993 and since then has published two survey reports of the Charsadda and Swabi Districts. 1 Dr. Abdur Rahman conducted survey of the Peshawar and Nowshera Districts and he will publish the report after analysis of the data. 2 Conducted by the present author, the current report is focussed on the archaeological survey of the Mardan District, also referred to as the Yusafzai Plain or District. -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

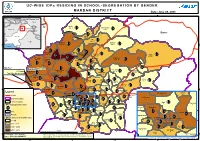

UC-WISE Idps RESIDING in SCHOOL-SEGREGATION BY

FANA U C - W I S E I D P s R E S I D I N G I N S C H O O L - S E G R E G AT I O N B Y G E N D E R UNOCHA M A R D A N D I S T R I C T Date :June 08, 2009 71°50'E 72°E 72°10'E 72°20'E Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Uzbekistan IDPs Intervention Area Tajikistan China Turkmenistan Pakistan Aksai Chin Kharki Jammu Kashmir ´ 406 ,6 Kohi Bermol Afghanistan 114 ,5 MalakCahina/dInd iPa A Buner PAKISTAN Qasmi Nepal 680 ,14 Iran Alo India 964 ,20 N N " Mian Issa Babozai " 0 0 3 3 ' ' 5 1638 ,40 222 ,8 5 2 2 ° ° 4 4 3 Arabian Sea 3 Shergarh Makori 959 ,19 Dherai Likpani 1028 ,16 Shamozai Bazar 1553 ,41 848 ,20 Lund Khawar 663 ,13 Hathian Pir Saddo 2911 ,41 Katlang-1 Palo Dheri 1631 ,21 Jalala 2760 ,18 Kati Garhi 928 ,15 1020 ,18 1741 ,16 572 ,15 Rustam 489 ,8 Katlang-2 Map Key: Takht Bhai 486 ,17 Mardan Kata Khat Parkho Dherai Jamal Garhi Chargalli UC Name Madey Baba 368 ,14 1927 ,35 183 ,6 383 ,11 1520 ,27 Sawal Dher Total IDPs, No of School 546 ,13 Daman-e-Koh Takkar 1317 ,5 1407 ,11 Kot Jungarah Mardan 2003 ,21 Machi Fathma Bakhshali Gujrat 91 ,4 Pat Baba 716 ,15 449 ,9 469 ,6 Narai 803 ,11 Garyala 948 ,21 Bala Garhi 711 ,15 Seri Bahlol 447 ,14 N N ' 1194 ,20 ' 5 Babini 5 1 Jehangir Abad 1 ° ° 4 Saro Shah 4 3 1092 ,11 725 ,10 Shahbaz Garhi 3 1139 ,16 Legend 340 ,12 Gujar Garhi Jehangir Abad Babini 1237 ,9 Mohib Banda 11 10 Roads Charsadda BaghdadaDagai Chak Hoti Baghicha Dheri 1451 ,11 707 ,16 528 ,8 156 ,4 212 ,5 Garhi Daulatzai Gujar Garhi District Boundary Mardan Rural 9 252 ,6 493 ,6 Chamtar Tehsil Boundary Dagai 267 ,8 Par Hoti Chak Hoti Khazana Dheri -

(BPS-14) on REGULAR BASIS UET MARDAN S. No Name F

APPLICATION OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POSITION OF ACCOUNT ASSISTANT (BPS-14) ON REGULAR BASIS UET MARDAN S. No Name Father’s Name Contact No Eligible Address Remarks 1. Zia Ullah Rahmat Shah 0321-9308381 // Jan abad Dosehra Road Mohalla New twon Mardan 2. Aftab Alam Alam zeb 0317-5884578 // Mohallah Bazid Khel , Village post office Kalu Khan 3. Waris Khan Nowraish Khan 0345-4250140 // District Mardan Tehsil Katlang village, Qasmi PO Tazagram Moh. Ayeen khan banda 4. Sardar Hussain Purdil Shah 0345-9356309 // House # 16-EGul Mohur Road University town Peshawar 5. Asim Noman Faiz Ur Rahman 0313-9198251 // Gahi Kapura Dulat Zai Mahalla Khandri Kheil Near Mama Masjid Mardan 6. Irfan ullah Roohid Din 0331-9235773 // Mohallah, Mianz Kandi Bughdada Mardan 7. Farhan Abbas Inayat ullah 0333-9044400 // Mohalla Islamabad No.2 Nowshera Road Charsadda 8. Aurang zeb Samar Gul 0345-9155882 Eligible The Bank of Khyber Lund Khwar 9. Faisal Khan Inam Ullah Khan 03488996851 // Moh. Haji Qadeem Khan, Village wazir Qarhi District Nowshera 10. Rafiq Ahmad Muhammad Gul 0311-3115185 // Accounts Section UET Mardan 11. Muhammad Imran Hamaish Gul 0333-5856705 // Mohallah, Baqal Khel Garhi Ismail zay Garhi Kapura District Mardan 12. Gul Khan Sher Bahadur 0346-9303531 // Village Qasmi, PO Tazagram Tehsil Katlang District Mardan 13. Arsalan Muhammad Muhammad Sadiq 0334-9412355 // Room No. F-13 Admin Block G.I.K Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology Topi Swabi 14. Fazl-I- Haq Sheran ul Haq 0311-1932924 // C/O Hamdil Khan COP state life Building 5th floor the Bank of Khyber Peshawar Cantt. 15.