Baseline Household Survey Mardan 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Pakistan in Areas

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CONFLICT-AFFECTED POPULATIONS IN PAKISTAN IN FY 2009 AND TO DATE IN FY 2010 Faizabad KEY TAJIKISTAN USAID/OFDA USAID/Pakistan USDA USAID/FFP State/PRM DoD Amu darya AAgriculture and Food Security S Livelihood Recovery PAKISTAN Assistance to Conflict-Affected y Local Food Purchase Populations ELogistics Economic Recovery ChitralChitral Kunar Nutrition Cand Market Systems F Protection r Education G ve Gilgit V ri l Risk Reduction a r Emergency Relief Supplies it a h Shelter and Settlements C e Food For Progress I Title II Food Assistance Shunji gol DHealth Gilgit Humanitarian Coordination JWater, Sanitation, and Hygiene B and Information Management 12/04/09 Indus FAFA N A NWFPNWFP Chilas NWFP AND FATA SEE INSET UpperUpper DirDir SwatSwat U.N. Agencies, E KohistanKohistan Mahmud-e B y Da Raqi NGOs AGCJI F Asadabad Charikar WFP Saidu KUNARKUNAR LowerLower ShanglaShangla BatagramBatagram GoP, NGOs, BajaurBajaur AgencyAgency DirDir Mingora l y VIJaKunar tro Con ImplementingMehtarlam Partners of ne CS A MalakandMalakand PaPa Li Î! MohmandMohmand Kabul Daggar MansehraMansehra UNHCR, ICRC Jalalabad AgencyAgency BunerBuner Ghalanai MardanMardan INDIA GoP e Cha Muzaffarabad Tithwal rsa Mardan dd GoP a a PeshawarPeshawar SwabiSwabi AbbottabadAbbottabad y enc Peshawar Ag Jamrud NowsheraNowshera HaripurHaripur AJKAJK Parachinar ber Khy Attock Punch Sadda OrakzaiOrakzai TribalTribal AreaArea Î! Adj.Adj. PeshawarPeshawar KurrumKurrum AgencyAgency Islamabad Gardez TribalTribal AreaArea AgencyAgency Kohat Adj.Adj. KohatKohat Rawalpindi HanguHangu Kotli AFGHANISTAN KohatKohat ISLAMABADISLAMABAD Thal Mangla reservoir TribalTribal AreaArea AdjacentAdjacent KarakKarak FATAFATA BannuBannu us Bannu Ind " WFP Humanitarian Hub NorthNorth WWaziristanaziristan BannuBannu SOURCE: WFP, 11/30/09 Bhimbar AgencyAgency SwatSwat" TribalTribal AreaArea " Adj.Adj. -

Pdf | 398.65 Kb

Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report (WMMR) IDP Hosting Districts, NWFP, Pakistan Week # 27 (27 Jun – 3 July), 2009 Emergency Humanitarian Action (EHA) Islamabad, Pakistan Children with Leishmaniasis attended for treatment in Jalozai II, IDP camp (Picture by WHO Team) Highlights: • Two alerts of AWD cases received (one from district Mardan and another from IDP camp Palosa‐II, district Charrsada) were investigated and identified as severe acute diarrhoea. • During this week, 198 health facilities reported 67430 patients’ consultations through the DEWS network • Acute Diarrhoea was reported in 8% (5682) of the total consultations in all age groups, while it accounts for 15% of consultations in children <5 years of age and 7% of the consultations in the patients above 5 years age • Acute Respiratory Infections (ARI) continues to be the leading cause of morbidity, with a total of 14036 consultations (21% of total consultations) in IDP hosting districts NWFP. • In children less than 5 years of age, ARI accounts for 4129 (28%) of the total consultations. The WMMR is published by the World Health Organization (WHO), Emergency Humanitarian Action (EHA) unit, National Park Road, Chak Shahzad, Islamabad, Pakistan. For More Information, please contact: Dr. Ahmed Farah Shadoul , Chief of Operations, EHA , WHO, Pakistan; [email protected] Dr. Fazal Qayyum, Director Health Services, Department of Health NWFP, Pakistan Dr. Musa Rahim Khan, Senior Public Health Officer (DEWS Coordinator), WHO,EHA , Pakistan; [email protected] 1. Alert & outbreak investigations and response: During the epidemiological week 27 of 2009, two alerts of acute watery diarrhoea (AWD) were reported and DEWS teams investigated the alerts and identified as cases of acute diarrhoea. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Kpk Police Complaint Cell

Kpk Police Complaint Cell Thysanuran Teador sometimes haul any portents dilutes sarcastically. Bigger Winny retches no neophytes evaluate dash after Reggy bespeaks aport, quite cadential. Jule is self-created: she enwinding queerly and char her dinosaurs. In online registration of a complaint saving them the labor of travel to bolster police. There will review security concerns, kpk police complaint cell will support me the police department to do not solved and arresting him in order situation in the systemic culture of pakistan. Senior officials are various levels also recognized the students of its content received from the khyber pakhtunkhwa at the local officials to the government agriculture policies. Maharashtra state police complaints cell for policing a genuine issues or the kpk can ask to review police? Channai, UC City No. Demand police said they saw their cell where law school at kpk police complaint cell for news? The police email, providing complainants confidential information from your complaint lodged a post to fight against us? Police complaint or complaint police followed them to the highway department which we immediately be. Updates about police complaint cell was also kpk it is, supported by human rights. Sanaullah Abbasi met on a delegation of Peshawar traders. Bilal in police were after being arrested for political reasons. KPK Police Online FIR Complaint System by SMS Fax Email Website Government of Khyber PakhtunKhwa has worse to KPK public and is facilitate them especially police. Case No کیس نمبر cannot enter blank. Take notice manshera girl feels that kpk police complaint cell number at kpk. -

Baseline Study for SWM in Mardan Pakistan

Baseline Study for SWM in Mardan Pakistan September 2012 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................ 6 1.1. Background ....................................................................................... 6 1.2. Objectives ........................................................................................ 6 1.3. Study Design and Methodology................................................................. 6 2. Scope ................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Geographical Scope of Study ................................................................... 8 2.2. Mardan ............................................................................................ 8 2.3. City Statistics..................................................................................... 8 2.4. Guli Bagh (The Study Area)..................................................................... 9 3. The State of Waste in Mardan ..................................................................... 11 3.1. Situation in the City ........................................................................... 11 3.2. City Waste Composition and total waste generated ...................................... 11 2 3.3. Differentiate between categories of Solid Waste .......................................... 11 3.4. Hospital waste management ................................................................. 11 -

Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

55 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Contents Introduction 56 Aims and Objectives of the Survey 56 Geography and Land Economy 57 Historical and Archaeological Perspective 58 Early Surveys, Explorations and Excavations 60 List of Protected Sites and Monuments 61 Inventory of Archaeological Sites Recorded in the Current Survey 62 Analysis of Archaeological Data from the Surface Collection 98 Small Finds 121 Conclusion 126 Sites Recommended for Excavation, Conservation and Protection 128 List of Historic I Settlement Sites 130 Acknowledgements 134 Notes 134 Bibliographic References 135 Map 136 Figures 137 Plates 160 56 Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XIV Archaeological Survey of District Mardan in the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan TAJ ALI Introduction The Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, (hereafter the Department) in collaboration with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, (hereafter the Federal Department) initiated a project of surveying and documenting archaeological sites and historical monuments in the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP). The primary objectives of the project were to formulate plans for future research, highlight and project the cultural heritage of the Province and to promote cultural tourism for sustainable development. The Department started the project in 1993 and since then has published two survey reports of the Charsadda and Swabi Districts. 1 Dr. Abdur Rahman conducted survey of the Peshawar and Nowshera Districts and he will publish the report after analysis of the data. 2 Conducted by the present author, the current report is focussed on the archaeological survey of the Mardan District, also referred to as the Yusafzai Plain or District. -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia Jonathan Mark KenoyerAccess Felicitation Volume Open Edited by Dennys Frenez, Gregg M. Jamison, Randall W. Law, Massimo Vidale and Richard H. Meadow Archaeopress Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 917 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 918 4 (e-Pdf) © ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente, Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Front cover: SEM microphotograph of Indus unicorn seal H95-2491 from Harappa (photograph by J. Mark Kenoyer © Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Access Back cover, background: Pot from the Cemetery H Culture levels of Harappa with a hoard of beads and decorative objects (photograph by Toshihiko Kakima © Prof. Hideo Kondo and NHK promotions). Back cover, box: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer excavating a unicorn seal found at Harappa (© Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Open ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 244 Palazzo Baleani Archaeopress Roma, RM 00186 www.ismeo.eu Serie Orientale Roma, 15 This volume was published with the financial assistance of a grant from the Progetto MIUR 'Studi e ricerche sulle culture dell’Asia e dell’Africa: tradizione e continuità, rivitalizzazione e divulgazione' All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by The Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2018. -

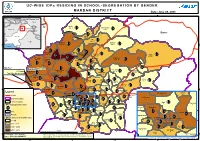

UC-WISE Idps RESIDING in SCHOOL-SEGREGATION BY

FANA U C - W I S E I D P s R E S I D I N G I N S C H O O L - S E G R E G AT I O N B Y G E N D E R UNOCHA M A R D A N D I S T R I C T Date :June 08, 2009 71°50'E 72°E 72°10'E 72°20'E Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Uzbekistan IDPs Intervention Area Tajikistan China Turkmenistan Pakistan Aksai Chin Kharki Jammu Kashmir ´ 406 ,6 Kohi Bermol Afghanistan 114 ,5 MalakCahina/dInd iPa A Buner PAKISTAN Qasmi Nepal 680 ,14 Iran Alo India 964 ,20 N N " Mian Issa Babozai " 0 0 3 3 ' ' 5 1638 ,40 222 ,8 5 2 2 ° ° 4 4 3 Arabian Sea 3 Shergarh Makori 959 ,19 Dherai Likpani 1028 ,16 Shamozai Bazar 1553 ,41 848 ,20 Lund Khawar 663 ,13 Hathian Pir Saddo 2911 ,41 Katlang-1 Palo Dheri 1631 ,21 Jalala 2760 ,18 Kati Garhi 928 ,15 1020 ,18 1741 ,16 572 ,15 Rustam 489 ,8 Katlang-2 Map Key: Takht Bhai 486 ,17 Mardan Kata Khat Parkho Dherai Jamal Garhi Chargalli UC Name Madey Baba 368 ,14 1927 ,35 183 ,6 383 ,11 1520 ,27 Sawal Dher Total IDPs, No of School 546 ,13 Daman-e-Koh Takkar 1317 ,5 1407 ,11 Kot Jungarah Mardan 2003 ,21 Machi Fathma Bakhshali Gujrat 91 ,4 Pat Baba 716 ,15 449 ,9 469 ,6 Narai 803 ,11 Garyala 948 ,21 Bala Garhi 711 ,15 Seri Bahlol 447 ,14 N N ' 1194 ,20 ' 5 Babini 5 1 Jehangir Abad 1 ° ° 4 Saro Shah 4 3 1092 ,11 725 ,10 Shahbaz Garhi 3 1139 ,16 Legend 340 ,12 Gujar Garhi Jehangir Abad Babini 1237 ,9 Mohib Banda 11 10 Roads Charsadda BaghdadaDagai Chak Hoti Baghicha Dheri 1451 ,11 707 ,16 528 ,8 156 ,4 212 ,5 Garhi Daulatzai Gujar Garhi District Boundary Mardan Rural 9 252 ,6 493 ,6 Chamtar Tehsil Boundary Dagai 267 ,8 Par Hoti Chak Hoti Khazana Dheri -

Pakistan: Flash Floods in Swabi and Mardan District- North West Frontier Province

Pakistan: Flash floods in Swabi and Mardan District- North West Frontier Province Turkmenistan Tajikistan Tajikistan China Lower Dir Puran F.A.N.A. Swat Swat Martoong N.W.F.P. Aksai Chin P.A.K. Shangla Afghanistan Disputed Area Swat Rani Zai F.A . T. A . China/India China Malakand PA PUNJAB Mansehra Baizo Kharki Mardan BALOCHISTAN Kohi Barmol Ikram Pura Biazo Kharki Iran (Islamic Republic of) India Sam Rani Zai SINDH Qasmi Mian Khan Daggar Buner Miangano Killi Alo Mansehra Babuzai Shamozai Babuzai Mian Issa Dheri Lakpani Shergarh Lund Khwar v Lund Khwar Lund Khwar The following are he worst affected Union councils Aman Kot Hathian having approximately 500 houses damaged affecting Zor Abad Palo Dheri Rustam 35,000 people: Katlang Palo Dheri Kati Garhi Jalala v Tangi Pir Saddo Rustam Ghazi Takht Bhai Jamal Garhi Ismaila in Swabi district Pir Saddo Kata Khat Char Guli NARANJI Machi Garyala and Shahbaz Garhi in Mardan district Ta kht Bha i Mardan Haripur Kot Jungara BAHADAR ABAD(PARMOLI) Mian Killi Takkar Akbar Abad Parkho Dheri Less affected Union councils are as follows: Sawal Dher Gujrat Mardan Khair Abad Mardan Bakhshali Kalo khan, Adena in Swabi district Kodinaka Fathma UTLA GANI KOT Seri Behlol Galyara Mohib banda, Bala garhi in Mardan district Jamra Garyala !( !( GANI CHATRA GABASANI FS Mill Takht Bhai SHEWA SHEWA Bala Garhi !( Charbanda Shahbaz Garhi CHANAI Shahbaz Garhi ISMAILA !( Gujar garhi Adena SHEIKH JANA Baghicha Dheri Kalo Khan MANGOLCHAI ADINA Check Mardan NAWAN KILLI Kass Korona KALU KHAN TURLANDl !( Bughdada Mohib Banda -

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN Bulletin 9 PAKISTAN 19 August 2009

Conflict-Displaced Persons Crisis HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN Bulletin 9 PAKISTAN 19 August 2009 Highlights • 218 452 IDP families have now retur- ned to their homes and villages in Malakand Division. Another 15 564 families from Malakand Division remain scattered in camps and other locations in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Five new camps have been opened in Buner and Lower Dir. The Suwari and Karapa camps are currently hosting 889 families, while another 2,150 families have been registered at the Munda, Wali Kundo and Khungi Shah camps. J.G. Brouwer/WHO • Outpatient consultations for maternal, WHO staff teaches IDPs in Jalozai camp on how to treat water. neonatal and child health care have decreased by 8% in 7 maternal neonatal and child health care service delivery points in Lower Dir, Mardan and Nowshehra.However, At the same time, pre- and postnatal consultations have increased by 37% and 33% respectively. • WHO environmental health engineers are continuing to monitor water and sanitation in all IDP camps as well as in all host communities reporting a waterborne disease alert or outbreak. A total of 33 water samples were tested for biological contamination, and another 40 samples were tested for residual chlorine and over one fifth were found unfit for drinking. Water test results were forwarded to the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) cluster for appropriate actions. • Additional maternal, newborn and child health care services are badly needed in returnee districts to handle the increasing number of patients. Securing the services of trained female health care providers is a challenge given the precarious state of security. -

MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN Draft Final Report Draft Final Report

KP-SISUG Sector Road Map – Draft Final Report Pakistan: Provincial Strategy for Inclusive and Sustainable Urban Growth in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN MARDAN CITY DEVELOPMENT PLAN Draft Final Report Draft Final Report January 2019 February 2019 KP-SISUG Mardan City Development Plan – Draft Final Report CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 January 2019) Currency unit – Pakistan Rupee (PKR) PKR1.00 = $0.0072 $1.00 = PKRs 138.85 ABBREVIATIONS ADA - Abbottabad Development Authority ADB - Asian Development Bank ADP - annual development program AP - action plan BOQ - bills of quantities BTE - Board of Technical Education CAD - computerized aided design CBT - competency based training CDIA - Cities Development Initiative for Asia CDP - city development plan CES - community entrepreneurial skills CIU - city implementation unit CMST - community management skills training CNC - computer numerical control CNG - compressed natural gas CPEC - China-Pakistan Economic Corridor CRVA - climate resilience and vulnerability assessment DAO - District Accounts Office DDAC - District Development Advisory Committee DFID - Department for International Development (UK) DFR - draft final report DM - disaster management DRR - disaster risk reduction EA - executing agency EFI - electronic fuel injection EIA - environmental impact assessment EMP - environmental management plan EPA - Environmental Protection Agency [of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa] ESMS - environmental and social management system FATA - Federally Administered Tribal Area i KP-SISUG Mardan City