Journal of Advanced Vehicle System 3, Issue 1 (2016) 1-13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estudios De Mercado El Mercado De Los Automóvi- Les En Malasia

Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Malasia El mercado de los Automóvi- les en Malasia 1 Estudios de Mercado El mercado de los Automóvi- les en Malasia Este estudio ha sido realizado por Joaquín Monreal bajo la supervisión de la Oficina Económica y Co- 2 Estudios de Mercado mercial de la Embajada de España en Kuala Lumpur Agosto de 2006 EL MERCADO DE LOS AUTOMOVILES EN MALASIA ÍNDICE RESUMEN Y PRINCIPALES CONCLUSIONES 4 I. INTRODUCCIÓN 5 1. Definición y características del sector y subsectores relacionados 5 2. Situación del sector en españa 8 II. ANÁLISIS DE LA OFERTA 10 1. Análisis cuantitativo 10 1.1. Tamaño de la oferta 10 2. Análisis cualitativo 12 2.1. Producción 12 2.2. Precios 14 2.3. Importaciones 16 2.4. Obstáculos comerciales: La NAP 29 2.5. El sistema de permisos para la matriculación 30 III. ANÁLISIS DEL COMERCIO 31 1. Canales de distribución 31 IV. ANÁLISIS DE LA DEMANDA 33 1. Evaluación del volumen de la demanda 33 1.1. Coyuntura económica. 33 1.2. Infraestucturas 34 1.3. Tendencias del consumo y situación del mercado nacional 34 1.4. Tendencias industriales 39 2. Estructura del mercado 39 3. Percepción del producto español 39 V. ANEXOS 41 1. Ensambladores de automóviles 41 2. Distribuidores y concesionarios 46 3. Informes de ferias 56 Oficina Económica y Comercial de la Embajada de España en Kuala Lumpur 3 EL MERCADO DE LOS AUTOMOVILES EN MALASIA RESUMEN Y PRINCIPALES CONCLUSIONES La industria de la automoción en Malasia es junto con la electrónica la industria más impor- tante en el sector manufacturero de Malasia, y de los más importantes dentro del Sudeste Asiático. -

Driving Growth Towards the Future

Head Office Jidosha Kaikan, Shiba Daimon 1-chome, Minato-ku Tokyo 105-0012 Japan Tel: +81-3-5405-6126 Fax: +81-3-5405-6136 DRIVING GROWTH http://www.jama.or.jp/ Singapore Branch North American Office 143 Cecil Street, 1050 17th Street, N.W., Suite 410 #09-03/04 GB Bldg. Washington, DC 20036-5518, USA TOWARDS THE FUTURE Singapore 069542 Tel: +1-202-296-8537 Tel: +65-6221-5057 Fax: +1-202-872-1212 Fax: +65-6221-5072 http://www.jama.org/ 2015 Beijing Representative European Office Office Avenue Louise 287 Unit 1001B, Level 10, 1050 Bruxelles, BELGIUM China World Office 2 Tel: +32-2-639-1430 No. 1 Fax: +32-2-647-5754 Jian Guo Men Wai Avenue Beijing, China 100004 Tel: +86-10-6505-0030 Fax: +86-10-6505-5856 KAWASAKI HEAVY INDUSTRIES, LTD. SUZUKI MOTOR CORPORATION DAIHATSU MOTOR CO., LTD. Kobe Head Office: Head Office: Head Office: Kobe Crystal Tower, 1-3, Higashi 300, Takatsuka-cho, Minami-ku, 1-1, Daihatsu-cho, Ikeda, Osaka 563-8651 Kawasaki-cho 1-chome Chuo-ku, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka 432-8611 Tel: +81(72)751-8811 Kobe, Hyogo 650-8680 Tel: +81(53)440-2061 Tokyo Office: Tel: +81(78)371-9530 Tokyo Branch: Shinwa Bldg, 2-10, Nihonbashi Hon-cho, Tokyo Head Office: Suzuki Bldg, Higashi-shimbashi 2F, 2-Chome, Chuo-ku, 2-2-8 Higashi-shinbashi, Tokyo 103-0023 1-14-5, Kaigan, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8315, Japan Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0021 Tel: +81(3)4231-8856 Tel: +81(3)5425-2158 http://www.daihatsu.com/ Tel: +81(3)3435-2111 http://www.khi.co.jp/ http://www.globalsuzuki.com/ FUJI HEAVY INDUSTRIES LTD. -

2012 MODEL VIN CODES This VIN Chart Is Available Online At

2012 MODEL VIN CODES This VIN chart is available online at www.mitsubishicars.com. Select “Owners”, ⇒ “Support”, ⇒ “VIN Information”, then select the appropriate year. Use this chart to decode Vehicle Identification Numbers for 2012 model year MMNA vehicles. VEHICLE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER 4 A 3 1 K 2 D F * C E 123456 1. Country of Mfg. 12 − 17 Plant Sequence No. 4 = USA (MMNA) J = Japan (MMC) 2. Manufacturer 11. Assembly Plant A = Mitsubishi E = Normal (USA) U = Mizushima 3. Vehicle Type Z = Okazaki 3 = Passenger Car 4 = Multi−Purpose Vehicle 10. Model Year 4. Restraint System C = 2012 All with Front Driver and Passenger Air Bags Passenger Car 1 = 1st Row Curtain + Seat Air Bags 9. Check Digit 2 = 1st & 2nd Row Curtain + Seat Air Bags 7 = Seat Mounted Air Bags MPV up to 5,000 lbs GVWR 8. Engine/Electric Motor A = 1st & 2nd Row Curtain + Seat Air Bags F = 2.4L SOHC MIVEC (4G69) MPV over 5,000 lbs GVWR S = 3.8L SOHC (6G75) J = 1st & 2nd Row Curtain + Seat Air Bags T = 3.8L SOHC MIVEC (6G75) U = 2.0L DOHC MIVEC (4B11) 5 & 6. Make, Car Line & Series V = 2.0L DOHC TC/IC MIVEC (4B11) B2 = Mitsubishi Galant FE (Fleet Package) W = 2.4L DOHC MIVEC (4B12) B3 = Mitsubishi Galant ES/SE X = 3.0L MIVEC (6B31) H3 = Mitsubishi RVR ES/SE (FWD) (Canada only) J3 = Mitsubishi RVR SE (4WD) (Canada only) 1 = 49Kw Electric Motor (Y4F1) J4 = Mitsubishi RVR GT (4WD) (Canada only) K2 = Mitsubishi Eclipse GS (M/T) 7. Type K3 = Mitsubishi Eclipse GT A = 5−door Wagon/SUV (Outlander, Outlander Sport) K5 = Mitsubishi Eclipse GS (A/T) / GS Sport / SE D = 3−door Hatchback -

Chapter 1 Introduction

The development of a hybrid knowledge-based Collaborative Lean Manufacturing Management (CLMM) system for an automotive manufacturing environment: The development of a hybrid Knowledge-Based (KB)/ Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)/ Gauging Absences of Pre-Requisites (GAP) Approach to the design of a Collaborative Lean Manufacturing Management (CLMM) system for an automotive manufacturing environment. Item Type Thesis Authors Moud Nawawi, Mohd Kamal Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 11:56:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/3353 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction Lean Manufacturing Management (LMM) is a management system that contains only required resources and materials, manufactures only required quantity of quality products on time that meet customers’ demands. The idea behind LMM is Manufacturing Planning and Control (MPC) system of the materials and information flow which involve both Manufacturing Resources Planning (MRP II), and Just-in-Time (JIT) techniques. In addition, Total Quality Management (TQM) is integrated to ensure the quality of the processes and products of the system. The capabilities of continuously improving the processes by identifying and eliminating manufacturing wastes are essential for effectiveness of LMM. The main benefit of effective LMM is high ratio of quality to cost of the products manufactured which finally contribute to high profitable organisation. -

Corporation Limited

Corporation Limited PRESS RELEASE JACKSPEED CORPORATION SECURES NEW CONTRACT TO SUPPLY AUTOMOTIVE LEATHER TRIM TO NAZA AUTOMOTIVE MANUFACTURING SDN BHD AND EXPANDS CAPACITY TO MEET ROBUST DEMAND - Invested in additional new equipment to enhance capacity in Kluang factory - Acquired a 19,035 sq m of land in Kedah, Malaysia to build additional production facility to cater to growing domestic market in Malaysia - Surge in OEM demand and capacity constraint reduced profit margins for FY04 Singapore, March 8, 2004 Jackspeed Corporation Limited ("Jackspeed"), an SGX-Mainboard-listed manufacturer of custom-fitted automotive leather trim for car seats and leather wrapping for automotive interior products, has secured a new contract from Naza Automotive Manufacturing Sdn Bhd (“Naza Automotive”). Naza Automotive is a member of Malaysia’s Naza Group of Companies, which assembles, markets and distributes the Kia range of vehicles, Malaysia’s third national car project. Jackspeed is currently a Tier One supplier of Naza Automotive. Jackspeed will supply a total of 10,000 sets of leather trim for Naza Automotive’s special edition vehicle – the National MPV for the Malaysian market. Delivery will be done over 3 years starting from this financial year. This is the second contract Jackspeed has secured from Naza Automotive in less than a year. Jackspeed has an existing contract to supply 30,000 sets of leather trim over 3 years from July 2003. To meet increased market demand, Jackspeed has expanded its production capacity in Malaysia. It has taken delivery of 69 new sewing machines for a total of about RM$600,000 (estimated S$290,000) for its Kluang factory in January 2004 and will recruit and train new employees to run these machines. -

Driving Growth Towards the Future 2014-2015 02

DRIVING GROWTH TOWARDS THE FUTURE 2014-2015 02 ASEAN-JAPAN Hand in Hand Towards The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ASEAN has been achieving high economic growth rates in recent Towards the goal of establishing the AEC, ASEAN has achieved years, with automobile production and sales volumes reaching a more than 80% of its AEC 2015 Blueprint measures, such as (1) record high in 2013. Japanese automotive manufacturers attained a a single market and production base, (2) strongly competitive total production of 3.87 million units (a 3% increase from last year), regional development, (3) equitable economic development, and sales of 3.09 million units (a 6% year-on-year increase) and exports (4) integration into the global economy. However, the elimination of 1.27 million units, representing a 23% increase over last year’s of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) trade facilitation, simplification of rules figures. In view of this favorable trend, JAMA member companies of origin, evaluation of standards vis-à-vis technical regulations, have been making active investments in ASEAN, bringing the and conformity assessment procedures remained important issues. combined number of factories and facilities to 83. The number Negotiations on these issues are underway among members. For of direct employees also increased 10% over last year, reaching the automotive industry in particular, it is hoped that the self- approximately 158,000. certification of origins currently being considered will be endorsed, promoting trade facilitation. In order to attain sustainable growth in the automotive industry, as well as other industries in the region, an ASEAN-centered economic On the technical front, JAMA hopes that the ASEAN Mutual integration agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Recognition Arrangement (MRA) for automotive technical Partnership (RCEP), was proposed, with official negotiations begun regulations will be practiced within an international framework in 2012. -

2011 Lancer Series

2011 Lancer Series At Mitsubishi, we believe not all drivers are created equal. So we build our vehicles for a different breed of driver, the fearless ones who take pride in what they drive, and refuse to drive more of the same. It’s obvious to us that people who truly want distinctive styling and the latest technology see past the procession of bland imitations. We believe that every vehicle we make should stand for something. Something more than expected. And that’s why we don’t build Mitsubishi cars for stereotypes. We build them for you. MITSUBISHICARS.COM / 1.888.MITSU2011 NATLBRO-11-002 Front Cover: Lancer Ralliart in Wicked White Lancer Evolution MR in Phantom Black How do you prefer your expectations exceeded? Whatever you’RE looking for IN A CAR, you’RE SURE to BE impressed. THE 2011 Mitsubishi LANCER line IS SO DIVERSE, IT WILL accommodate ANY inclination AND surpass virtually ANY assumption you might HOLD ABOUT CARS IN its class. Its HIGH-TECH features alone WILL stop you IN your tracks. That is, until you discover how easily THEY HELP you navigate those tracks. IF MUSIC IS your passion, its audio system WILL captivate EVEN THE most DISCERNING EAR. ARE ENGINES your PRIORITY? LANCER OFFERS everything FROM economical to formidable performance. SO WHY limit your expectations? WITH LANCER, you CAN have your astonishment ANY way you LIKE. Mitsubishicars.com Don’t put the world on hold when the open road calls. 40GB Hard Disc Drive Navigation System and Music Server Call it your own rapid transit authority, Lancer’s available 40-gigabyte navigation system not only offers ultrafast data access, it provides a wealth of useful features like Real-Time Traffic and Diamond Lane Guidance™ to help speed you to your destination. -

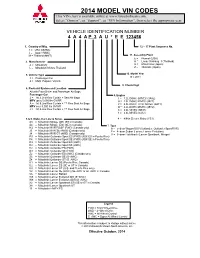

2014 MODEL VIN CODES This VIN Chart Is Available Online At

2014 MODEL VIN CODES This VIN chart is available online at www.mitsubishicars.com. Select “Owners”, ⇒ “Support”, ⇒ “VIN Information”, then select the appropriate year. VEHICLE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER 4 A 4 A P 3 A U * E E 123456 1. Country of Mfg. 12 − 17 Plant Sequence No. 4 = USA (MMNA) J = Japan (MMC) M = Thailand (MMT) 11. Assembly Plant E = Normal (USA) 2. Manufacturer H = Laem Chabang−3 (Thailand) A = Mitsubishi U = Mizushima (Japan) L = Mitsubishi Motors Thailand Z = Okazaki (Japan) 3. Vehicle Type 10. Model Year 3 = Passenger Car E = 2014 4 = Multi−Purpose Vehicle 9. Check Digit 4. Restraint System and Location All with Front Driver and Passenger Air Bags Passenger Car 8. Engine/Electric Motor 2 = 1st & 2nd Row Curtain + Seat Air Bags J = 1.2L DOHC (MIVEC (3A92) MPV up to 5,000 lbs GVWR U = 2.0L DOHC MIVEC (4B11) st A = 1st & 2nd Row Curtain + 1 Row Seat Air Bags V = 2.0L DOHC TC/IC MIVEC (4B11) MPV over 5,000 lbs GVWR W = 2.4L DOHC MIVEC (4B12) st J = 1st & 2nd Row Curtain + 1 Row Seat Air Bags X = 3.0L MIVEC (6B31) 3 = 2.4L MIVEC (4J12) 5 & 6. Make, Car Line & Series 4 = 49Kw Electric Motor (Y51) A3 = Mitsubishi Mirage (DE) (ES in Canada) A4 = Mitsubishi Mirage (ES) (SE in Canada) 7. Type H3 = Mitsubishi RVR ES/SE (FWD) (Canada only) A = 5−door Wagon/SUV (Outlander, Outlander Sport/RVR) J3 = Mitsubishi RVR SE (4WD) (Canada only) F = 4−door Sedan (Lancer, Lancer Evolution) J4 = Mitsubishi RVR GT (4WD) (Canada only) H = 5−door Hatchback (Lancer Sportback, Mirage) “i” MiEV P3 = Mitsubishi Outlander Sport ES (FWD) (ASX ES in Puerto Rico) P4 = Mitsubishi Outlander Sport SE (FWD) (ASX SE in Puerto Rico) R3 = Mitsubishi Outlander Sport ES (AWC) R4 = Mitsubishi Outlander Sport SE (AWC) D2 = Mitsubishi Outlander ES (FWD) D3 = Mitsubishi Outlander SE (FWD) Z2 = Mitsubishi Outlander ES (AWC) (Canada only) Z3 = Mitsubishi Outlander SE (S−AWC) Z4 = Mitsubishi Outlander GT (S−AWC) U1 = Mitsubishi Lancer DE (Puerto Rico, Canada) U2 = Mitsubishi Lancer ES (SE or GT in Canada) U8 = Mitsubishi Lancer GT (U.S. -

Corporation Limited

Corporation Limited PRESS RELEASE Jackspeed Corporation Limited Wins RM55 million Contract from Naza Automotive Manufacturing Sdn Bhd • Jackspeed's Malaysian subsidiary will supply leather trims for Naza’s New MPV project for three years Singapore, September 13, 2004 – SGX Mainboard-listed Jackspeed Corporation Limited (“Jackspeed””), a manufacturer of custom-fitted automotive leather trim for car seats and leather wrapping for automotive interior products, has secured a RM 55 million contract from Naza Automotive Manufacturing Sdn Bhd (“Naza Automotive”). This is its third and also single largest contract that Naza Automotive has awarded to Jackspeed. The contract is for the company’s Malaysian subsidiary to supply leather trims for Naza’s new MPV project for three years, starting on November 2004. Naza Automotive assembles, markets and distributes the Naza range of vehicles for its third national car project. Jackspeed is currently a Tier One supplier of Naza Automotive. Commenting on the new contract win, Mr Jackson Liew, Jackspeed’s Group Chairman and CEO said, "This latest contract with Naza Automotive is a strong testament to their trust and confidence in our high standards of quality and delivery. We see tremendous potential in the automotive industry in Malaysia. With the implementation of AFTA and reduction of tariffs, the region’s automotive industry is expected to enjoy robust growth. This will also drive further growth in the automotive manufacturing sector in Malaysia. Jackspeed, which already has an established presence in Malaysia, is well-poised to take advantage of new opportunities in the auto sector and ride on its vibrant growth. Mr Liew said that this major contract win will further reinforce its relationship with Naza Automotive and strengthen its stronghold in the Malaysian automotive industry. -

Investigation of Ergonomics Design of Car Boot for Proton Saga (BLM) and Perodua (Myvi)

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395 -0056 Volume: 03 Issue: 08 | Aug-2016 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Investigation of Ergonomics Design of Car Boot for Proton Saga (BLM) and Perodua (Myvi) KA Shamsuddin1, SF Hannan2, TAA Razak3, KS Shafee4 1 Lecturer, Mechanical Section, Universiti Kuala Lumpur (UniKL), Malaysian Spanish Institute (MSI), Malaysia 2 Lecturer, Mechanical Section, Universiti Kuala Lumpur (UniKL), Malaysian Spanish Institute (MSI), Malaysia 3 Lecturer, Mechanical Section, Universiti Kuala Lumpur (UniKL), Malaysian Spanish Institute (MSI), Malaysia 4 Lecturer, Mechanical Section, Universiti Kuala Lumpur (UniKL), Malaysian Spanish Institute (MSI), Malaysia ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract – Ergonomics is as study of human posture. It Ergonomics is new principles, methods and data drawn concentrated on how to achieve mental and physical from a multi sources to develop engineering system in which human play a significant role. In performing an comfort. This is a new principles, methods and data drawn ergonomics studies, human variability is used as a design from a multi sources to develop engineering system in which parameter. The term success in ergonomics is measured human play a significant role. In performing ergonomics by improved productivity, efficiency, safety, acceptance of study, human variability is used as a design parameter. The the resultant system design and improved quality of term success in ergonomics is measured by improved human life (Kroemer & Kroemer-Albert 2001). The productivity, efficiency, safety, acceptance of the resultant importance of the relationship between humans and tools as it was realized in early development of the product system design and improved quality of human life. -

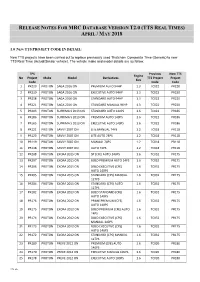

Release Notes for Mrc Database Version T2.0 (Tts Real Times) April / May 2018

RELEASE NOTES FOR MRC DATABASE VERSION T2.0 (TTS REAL TIMES) APRIL / MAY 2018 1.0 NEW TTS PROJECT CODE IN DETAIL: New TTS projects have been carried out to replace previously used Thatcham Composite Time (Generic) to new TTS Real Time (Actual/Similar vehicle). The vehicle make and model details are as follow: TPS Previous New TTS Engine No Project Make Model Derivatives TTS Project Project Size Code Code Code 1 PR220 PROTON SAGA 2016 ON PREMIUM AUTO 94HP 1.3 TC022 PR220 2 PR219 PROTON SAGA 2016 ON EXECUTIVE AUTO 94HP 1.3 TC022 PR220 3 PR218 PROTON SAGA 2016 ON STANDARD AUTO 94HP 1.3 TC022 PR220 4 PR221 PROTON SAGA 2016 ON STANDARD MANUAL 94HP 1.3 TC022 PR220 5 PR203 PROTON SUPRIMA S 2013 ON STANDARD AUTO 140PS 1.6 TC022 PR186 6 PR186 PROTON SUPRIMA S 2013 ON PREMIUM AUTO 140PS 1.6 TC022 PR186 7 PR165 PROTON SUPRIMA S 2013 ON EXECUTIVE AUTO 140PS 1.6 TC022 PR186 8 PR121 PROTON SAVVY 2007 ON LITE MANUAL 74PS 1.2 TC018 PR118 9 PR120 PROTON SAVVY 2007 ON LITE AUTO 74PS 1.2 TC018 PR118 10 PR119 PROTON SAVVY 2007 ON MANUAL 74PS 1.2 TC018 PR118 11 PR118 PROTON SAVVY 2007 ON AUTO 74PS 1.2 TC018 PR118 12 PR208 PROTON EXORA 2015 ON SP (CFE) AUTO 140PS 1.6 TC032 PR175 13 PR207 PROTON EXORA 2015 ON BOLD PREMIUM AUTO 14PS 1.6 TC032 PR175 14 PR206 PROTON EXORA 2015 ON BOLD EXECUTIVE (CFE) 1.6 TC032 PR175 AUTO 140PS 15 PR205 PROTON EXORA 2015 ON STANDARD (CPS) MANUAL 1.6 TC032 PR175 127PS 16 PR204 PROTON EXORA 2015 ON STANDARD (CPS) AUTO 1.6 TC032 PR175 127PS 17 PR182 PROTON EXORA 2013 ON BOLD STANDARD (CFE) 1.6 TC032 PR175 AUTO 140PS 18 PR176 PROTON -

2WD Back-Up Camera Brake Assist

6030 Sycamore Canyon Blvd. RACEWAY NISSAN Riverside, CA, 92507 Stock: N25804B 2015 MITSUBISHI LANCER GT VIN: JA32U8FW3FU011582 Original Price CALL US Current Sale Price: $9,342 93,048 miles Front Wheel Drive 4 cylinders VEHICLE DETAILS 2WD Back-up Camera Brake Assist Steering Wheel Remote Keyless Keyless Entry Controls Entry Security System 10/02/2021 12:20 https://www.racewaynissan.com/inventory/used-2015-Mitsubishi-Lancer-GT-JA32U8FW3FU011582 Mon - Fri: 8:30am - 7:00pm 6030 Sycamore Canyon Blvd. Sat: 8:30am - 7:00pm Riverside, CA, 92507 866-813-5092 Sun: 9:00am - 7:00pm 6030 Sycamore Canyon Blvd. RACEWAY NISSAN Riverside, CA, 92507 Stock: N25804B 2015 MITSUBISHI LANCER GT VIN: JA32U8FW3FU011582 EXTERIOR 4-Wheel Disc Brakes Electronic Stability Control 18" Alloy Wheels Four wheel independent suspension Spoiler Front anti-roll bar Alloy wheels Bumpers: body-color Front fog lights SAFETY Heated door mirrors ABS brakes Power door mirrors Brake assist Turn signal indicator mirrors Dual front impact airbags Variably intermittent wipers Dual front side impact airbags Speed-Sensitive Wipers Knee airbag Wireless phone connectivity: Bluetooth Low tire pressure warning Exterior Parking Camera Rear Occupant sensing airbag Overhead airbag INTERIOR Panic alarm Power steering AM/FM/CD/MP3 Audio System Rear anti-roll bar 6 Speakers Traction control Air Conditioning Front Bucket Seats Front Center Armrest OTHER Leather Shift Knob Sport Front Bucket Seats Tachometer Sport Fabric Seating Surfaces Automatic temperature control FUSE Handsfree Bluetooth w/USB Port CD player Driver door bin Driver vanity mirror COMMENTS Front reading lights We're Open and We Deliver! Test drives available at your home or office across Riverside Illuminated entry County.