Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Bills of Attainder

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship Winter 2016 Bills of Attainder Matthew Steilen University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Matthew Steilen, Bills of Attainder, 53 Hous. L. Rev. 767 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE BILLS OF ATTAINDER Matthew Steilen* ABSTRACT What are bills of attainder? The traditional view is that bills of attainder are legislation that punishes an individual without judicial process. The Bill of Attainder Clause in Article I, Section 9 prohibits the Congress from passing such bills. But what about the President? The traditional view would seem to rule out application of the Clause to the President (acting without Congress) and to executive agencies, since neither passes bills. This Article aims to bring historical evidence to bear on the question of the scope of the Bill of Attainder Clause. The argument of the Article is that bills of attainder are best understood as a summary form of legal process, rather than a legislative act. This argument is based on a detailed historical reconstruction of English and early American practices, beginning with a study of the medieval Parliament rolls, year books, and other late medieval English texts, and early modern parliamentary diaries and journals covering the attainders of Elizabeth Barton under Henry VIII and Thomas Wentworth, earl of Strafford, under Charles I. -

Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided by Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England Laura Christine Oliver, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D. This thesis argues that while patriarchy was certainly present in England during the late medieval period, women of the middle and upper classes were able to exercise agency to a certain degree through using both the patriarchal bargain and an economy of makeshifts. While the methods used by women differed due to the resources available to them, the agency afforded women by the patriarchal bargain and economy of makeshifts was not limited to the aristocracy. Using Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe as cases studies, this thesis examines how these women exercised at least a limited form of agency. Additionally, this thesis examines whether ordinary women have access to the same agency as elite women. Although both were exceptional women during this period, they still serve as ideal case studies because of the sources available about them and their status as role models among their contemporaries. “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided By Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England by Laura Christine Oliver, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Julie A. -

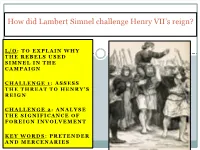

How Did Lambert Simnel Challenge Henry VII's Reign?

How did Lambert Simnel challenge Henry VII’s reign? L/O : TO EXPLAIN WHY THE REBELS USED SIMNEL IN THE CAMPAIGN CHALLENGE 1 : A S S E S S THE THREAT TO HENRY’S REIGN CHALLENGE 2 : A N A L Y S E THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT K E Y W O R D S : PRETENDER AND MERCENARIES First task-catch up on the background reading… https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/tudor- england/the-lambert-simnel-rebellion/ When you find someone you have not heard of, please take 5 minutes to Google them and jot down a few notes. Starting point… Helpful tip: Before you start to race through this slide, make sure that you know something about the Battle of Bosworth, the differences between Yorkists and Lancastrians and the story behind the Princes in the Tower. In the meantime - were the ‘Princes in the Tower’ still alive? Richard III and Henry VII both had the problem of these princely ‘threats’ but if they were dead who would be the next threat? Possibly, Edward, Earl of Warwick who had a claim to the throne What is a ‘pretender’ ? Royal descendant those throne is claimed and occupied by a rival, or has been abolished entirely. OR …an individual who impersonates an heir to the throne. The Role of Oxford priest Symonds was Lambert Simnel’s tutor Richard Symonds Yorkist Symonds thought Simnel looked like one of the Princes in the Tower Plotted to use him as a focus for rebellion – tutored him in ‘princely skills’ Instead, he changed his mind and decided to use him as an Earl of Warwick look-a-like Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy Sister of Edward IV and Richard -

The National Archives Prob 11/63/590 1 ______

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/63/590 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the will, dated 18 April 1581, together with a codicil dated 6 May 1581 and a nuncupative codicil dated 10 May 1581, proved 23 November 1581, of Sir William Cordell (1522 – 17 May 1581), Master of the Rolls, and one of the five trustees appointed by Oxford in an indenture of 30 January 1575 prior to his departure on his continental tour. See ERO D/DRg2/25. For a copy of the testator’s will of lands, dated 1 January 1581, see Howard, Joseph Jackson, ed., The Visitation of Suffolke, (Lowestoft: Samuel Tymms, 1866), Vol. I, pp. 248-59 at: https://books.google.ca/books?id=ExI2AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA248 In the will below the testator states that he had been executor to Sir Roger Cholmley (c.1485–1565), whose daughter, Frances Cholmley, was the first wife of Sir Thomas Russell (c.1520 - 9 April 1574) of Strensham, who by his second wife, Margaret Lygon, was the father of Thomas Russell (1570-1634), overseer of the will of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon. The testator was appointed supervisor of the will, TNA PROB 11/51/33, of Edmund Beaupre (d. 14 February 1568), esquire, for whose connection to John de Vere (1516- 1562), 16th Earl of Oxford, see the inquisition post mortem taken at Stratford Langthorne on 18 January 1563, five months after the Earl’s death, TNA C 142/136/12: And the foresaid jurors moreover say that before the death of the foresaid late Earl -

English Without Boundaries

English Without Boundaries English Without Boundaries: Reading English from China to Canada Edited by Jane Roberts and Trudi L. Darby English Without Boundaries: Reading English from China to Canada Edited by Jane Roberts and Trudi L. Darby This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Jane Roberts, Trudi L. Darby and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9588-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9588-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations .................................................................................. viii List of Tables .............................................................................................. ix Foreword ..................................................................................................... x Thomas Austenfeld Introduction .............................................................................................. xii Jane Roberts and Trudi L. Darby Part I: Poets and Playwrights Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 William Herbert and Richard Neville: Poetry -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

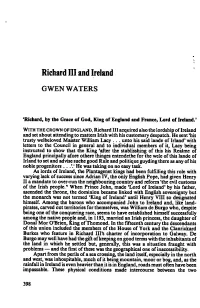

Richard III and Ireland GWEN WATERS ‘Richard, by the Grace of God, King of England and France, Lord of Ireland.’ WITH THE CROWN OF ENGLAND,Richard III acquired also the lordship of Ireland and set about attending to matters Irish with his customary despatch. He sent ‘his trusty welbeloved Maister William Lacy . unto his said lande of Irland’ with letters to the Council in general and to individual members of it, Lacy being instructed to show that the King ‘after the stablisshing of this his Realme of England principally afore othere thinges entendethe for the wele of this lands of Irland to set and advise suche good Rule and politique guyding there as any of his noble progenitors . .’.' He was taking on no easy task. As lords of Ireland, the Plantagenet kings had been fulfilling this role with varying lack of success since Adrian IV, the only English Pope, had given Henry II a mandate to over-run the neighbouring country and reform ‘the evil customs of the Irish people.” When Prince John, made ‘Lord of Ireland' by his father, ascended the throne, the dominion became linked with English sovereignty but the monarch was not termed ‘King of Ireland’ until Henry VIII so designated himself. Among the barons who accompanied John to Ireland and, like land- pirates, carved out territories for themselves, was William de Burgo who, despite being one of the conquering race, seems to have established himself successfully among the native people and, in 1193, married an Irish princess, the daughter of Donal Mor O'Brien, King of Thomond. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

5 Tudor Textbook for GCSE to a Level Transition

Introduction to this book The political context in 1485 England had experienced much political instability in the fifteenth century. The successful short reign of Henry V (1413-22) was followed by the disastrous rule of Henry VI. The shortcomings of his rule culminated in the s outbreak of the so-called Wars of the Roses in 1455 between the royal houses of Lancaster and York. England was then subjected to intermittent civil war for over thirty years and five violent changes of monarch. Table 1 Changes of monarch, 1422-85 Monarch* Reign The ending of the reign •S®^^^^^3^^!6y^':: -; Defeated in battle and overthrown by Edward, Earl of Henry VI(L] 1422-61 March who took the throne. s Overthrown by Warwick 'the Kingmaker' and forced 1461-70 Edward IV [Y] into exile. Murdered after the defeat of his forces in the Battle of Henry VI [L] 1470-?! Tewkesbury. His son and heir, Edward Prince of Wales, was also killed. Died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving as his heir 1471-83 Edward IV [Y] the 13-year-old Edward V. Disappeared in the Tower of London and probably murdered, along with his brother Richard, on the orders of Edward V(Y] 1483 his uncle and protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who succeeded him on the throne. Defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard III [Y] 1483-85 Succeeded on the throne by his successful adversary Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. •t *(L]= Lancaster [Y)= York / Sence Brook RICHARD King Dick's Hole ao^_ 00/ g •%°^ '"^. 6'^ Atterton '°»•„>••0' 4<^ Bloody. -

Bosworth: the Dawn of the Tudors

Bosworth: the dawn of the Tudors From childhood imprisonment in Brittany to the violent execution of Richard III in a Leicestershire field, Henry Tudor's passage to the throne was lengthy and labyrinthine. Chris Skidmore charts the origins of the Tudor dynasty This competition is now closed Wales, 7 August 1485. As the sun lowered beneath the horizon across the Milford estuary, a flotilla of ships drifted across the mouth of the Haven. It had been a week since the fleet had sailed from the shelter of the Seine at Honfleur, but the ships had made fast progress in the balmy August weather. Onboard, the soldiers waited. They included a rabble of 2,000 Breton and French soldiers (many only recently released from prison and, according to the chronicler Commynes, “the worst sort… raised out of the refuse of the people”). There were also a thousand Scottish troops and 400 Englishmen, whose last sight of the country had been two years previously, when they had fled in fear of their lives. The ships entered the mouth of the estuary where, looking leftwards, the dark red sandstone cliffs, several hundred feet in height and impossible to scale, gave way to a small cove hiddenrom sight from the cliffs above. High tide had passed an hour previously, enabling the ships to creep silently to the edge of the narrow shoreline, allowing the troops to disembark. Their arrival stirred no one. The waters soon clouded with sand as the men began to heave cannon, guns and ordnance from the boats, leading horses from the ships and onto land. -

Inspiration from Kick@Ss Tudor Women Day One: Lady Margaret Beaufort

Inspiration from Kick@ss Tudor Women Day One: Lady Margaret Beaufort Hello and welcome to Day One of the Inspiration from Kickass Tudor Women minicourse. My name is Heather Teysko, and for those of you who don’t know me, I started a podcast called the Renaissance English History Podcast in 2009, and have been podcasting for the past eight years about my favorite time period in history. I also lead history tours to England, design gorgeous planners and journals inspired by Tudor history, and do courses on podcasting. I live in Spain with my husband and three year old daughter, and before that I lived in London, New York, Los Angeles, and I’m originally from Amish Country Pennsylvania. So that’s a little bit about who I am. As this course goes on, I want to know more about who you are, about what inspires you about history, and what you get out of learning about it. My first job in high school was as a student docent at a local home built by a Revolutionary War general, Rock Ford Plantation in Lancaster PA, owned by General Edward Hand, adjutant general to Washington. I spent five years there, and during that time I got to know Edward Hand really well. I handled his medical equipment, I touched his books, and I got to know him really well. But I really didn’t know much about his wife. And, as someone who loved history, but also was interested in women’s history, that really bugged me. There are a lot of reasons why women don’t make it into the historical narrative. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

The Lisle Letters: Lady Honor Lisle’s epistolary influence by Jasmine Nicholsfigueiredo B.Ed., Simon Fraser University, 2004 M.A. English, Queen’s University, 2002 B.A. English, Simon Fraser University, 2001 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Jasmine Nicholsfigueiredo 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2014 Approval Name: Jasmine Nicholsfigueiredo Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title: The Lisle Letters: Lady Honor Lisle’s Epistolary Influence Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Jon Smith Associate Professor Dr. Paul Delany Senior Supervisor Professor Emeritus Dr. Lara Campbell Supervisor Associate Professor Chair of the Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Dr. Anne Higgins Internal Examiner Associate Professor Dr. Holly Nelson External Examiner Associate Professor Department of English Trinity Western University Date Defended: May 5, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This dissertation offers an original contribution to Tudor studies by examining The Lisle Letters as an illuminating example of how aristocratic Tudor women used the epistle to manipulate networks of obligation and gain socio-political influence. Women, such as Lady Honor Lisle, the primary subject of this study, fashioned letters to create and maintain communities of influence in order to assist their families, advance their social position, and bring various other projects to fruition. By using the lens of practice theory to examine the Lisle Letters, I will demonstrate that the relational aspects governing an individual’s agency, in the light of ever-changing variables – friends, kinship groups, societal knowledge, socio-economic status, and so on – are what allowed aristocratic women such as Lady Lisle to exercise influence, despite the fact they could not hold official positions of power, such as judge, magistrate, or Lord Privy Seal.