Perkin Warbeck (NZ Version)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided by Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England Laura Christine Oliver, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D. This thesis argues that while patriarchy was certainly present in England during the late medieval period, women of the middle and upper classes were able to exercise agency to a certain degree through using both the patriarchal bargain and an economy of makeshifts. While the methods used by women differed due to the resources available to them, the agency afforded women by the patriarchal bargain and economy of makeshifts was not limited to the aristocracy. Using Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe as cases studies, this thesis examines how these women exercised at least a limited form of agency. Additionally, this thesis examines whether ordinary women have access to the same agency as elite women. Although both were exceptional women during this period, they still serve as ideal case studies because of the sources available about them and their status as role models among their contemporaries. “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided By Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England by Laura Christine Oliver, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Julie A. -

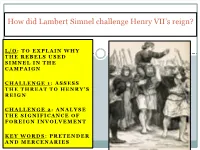

How Did Lambert Simnel Challenge Henry VII's Reign?

How did Lambert Simnel challenge Henry VII’s reign? L/O : TO EXPLAIN WHY THE REBELS USED SIMNEL IN THE CAMPAIGN CHALLENGE 1 : A S S E S S THE THREAT TO HENRY’S REIGN CHALLENGE 2 : A N A L Y S E THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT K E Y W O R D S : PRETENDER AND MERCENARIES First task-catch up on the background reading… https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/tudor- england/the-lambert-simnel-rebellion/ When you find someone you have not heard of, please take 5 minutes to Google them and jot down a few notes. Starting point… Helpful tip: Before you start to race through this slide, make sure that you know something about the Battle of Bosworth, the differences between Yorkists and Lancastrians and the story behind the Princes in the Tower. In the meantime - were the ‘Princes in the Tower’ still alive? Richard III and Henry VII both had the problem of these princely ‘threats’ but if they were dead who would be the next threat? Possibly, Edward, Earl of Warwick who had a claim to the throne What is a ‘pretender’ ? Royal descendant those throne is claimed and occupied by a rival, or has been abolished entirely. OR …an individual who impersonates an heir to the throne. The Role of Oxford priest Symonds was Lambert Simnel’s tutor Richard Symonds Yorkist Symonds thought Simnel looked like one of the Princes in the Tower Plotted to use him as a focus for rebellion – tutored him in ‘princely skills’ Instead, he changed his mind and decided to use him as an Earl of Warwick look-a-like Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy Sister of Edward IV and Richard -

Content Overview: Assessment Overview

Content Overview: Assessment Overview: British period study and enquiry: (unit group 1) Learners study one of the 13 units British period study and 25% available, each of which constitutes a substantial and coherent element of British enquiry (Y101-Y113) 50 of total History. The enquiry is a source-based study which immediately precedes or marks 1 hour 30 minute A level follows the outline period study paper Non-British period study: (unit group 2) Learners study one of the 24 units Non-British period study 15% available, each of which constitutes a coherent period of non-British History. (Y201-Y224) 30 marks 1 of total hour paper A level Thematic study and historical interpretations: (unit group 3) Learners study one of Thematic study and 40% the 21 units available. Each unit comprises a thematic study over a period of at historical interpretations of total least 100 years, and three in-depth studies of events, individuals or issues that are (Y301-Y321) 80 marks 2 A level key parts of the theme. Learners will develop the ability to treat the whole period hour 30 minute paper thematically, and to use their detailed knowledge of the depth study topics to evaluate interpretations of the specified key events, individuals or issues Topic based essay: (unit Y100)* ** Learners will complete a 3000–4000 word 3000–4000 word essay 20% essay on a topic of their choice, which may arise out of content studied elsewhere (Y100/03 or 04) Non of total in the course. This is an internally assessed unit group. A Title(s) Proposal Form exam assessment 40 marks A level must be submitted to OCR. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

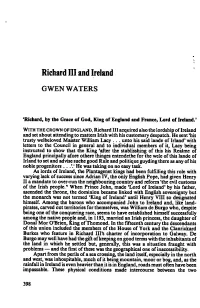

Richard III and Ireland GWEN WATERS ‘Richard, by the Grace of God, King of England and France, Lord of Ireland.’ WITH THE CROWN OF ENGLAND,Richard III acquired also the lordship of Ireland and set about attending to matters Irish with his customary despatch. He sent ‘his trusty welbeloved Maister William Lacy . unto his said lande of Irland’ with letters to the Council in general and to individual members of it, Lacy being instructed to show that the King ‘after the stablisshing of this his Realme of England principally afore othere thinges entendethe for the wele of this lands of Irland to set and advise suche good Rule and politique guyding there as any of his noble progenitors . .’.' He was taking on no easy task. As lords of Ireland, the Plantagenet kings had been fulfilling this role with varying lack of success since Adrian IV, the only English Pope, had given Henry II a mandate to over-run the neighbouring country and reform ‘the evil customs of the Irish people.” When Prince John, made ‘Lord of Ireland' by his father, ascended the throne, the dominion became linked with English sovereignty but the monarch was not termed ‘King of Ireland’ until Henry VIII so designated himself. Among the barons who accompanied John to Ireland and, like land- pirates, carved out territories for themselves, was William de Burgo who, despite being one of the conquering race, seems to have established himself successfully among the native people and, in 1193, married an Irish princess, the daughter of Donal Mor O'Brien, King of Thomond. -

Anne Neville: Queen to Richard Iii Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANNE NEVILLE: QUEEN TO RICHARD III PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Hicks | 224 pages | 28 Sep 2007 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752441290 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Anne Neville: Queen to Richard III PDF Book Perhaps she would have become Elizabeth of York's lady-in-waiting, or sought sanctuary until she was financially able to support herself or re- marry. Anne was buried in Westminster Abbey in an unmarked grave, which seems quite unfitting for a Queen of England. Jone Johnson Lewis is a women's history writer who has been involved with the women's movement since the late s. England's Forgotten Queens. A splendid service featured the Te Deum before the royal couple proceeded to the adjacent palace of the archbishop. This account has come down to us from Polydore Vergil, although possible Tudor exaggeration must also be taken into consideration here, to allow for further intent to vilify Richard, given the fact that Vergil was writing for Henry VII. Community Reviews. Medieval officers wanted assurance and authorisation for their actions — by what warrant did you act? April 26, at pm. Thomas le Despenser, 1st Earl of Gloucester 7. Clarence attempted to take Anne in as his ward in order to control her inheritance. Another possibility could be an attack of influenza, which combined with a weak immune system and other ailments could be fatal. Royal princes, who were not expected to become kings, followed the example of the nobility, wedding heiresses who could bring them great estates and hence great power. July 9, at pm. Adopted Escutcheon Quarterly , 1st and 4th, France moderne, 2nd and 3rd England; impaled with Gules, a saltire Argent. -

5 Tudor Textbook for GCSE to a Level Transition

Introduction to this book The political context in 1485 England had experienced much political instability in the fifteenth century. The successful short reign of Henry V (1413-22) was followed by the disastrous rule of Henry VI. The shortcomings of his rule culminated in the s outbreak of the so-called Wars of the Roses in 1455 between the royal houses of Lancaster and York. England was then subjected to intermittent civil war for over thirty years and five violent changes of monarch. Table 1 Changes of monarch, 1422-85 Monarch* Reign The ending of the reign •S®^^^^^3^^!6y^':: -; Defeated in battle and overthrown by Edward, Earl of Henry VI(L] 1422-61 March who took the throne. s Overthrown by Warwick 'the Kingmaker' and forced 1461-70 Edward IV [Y] into exile. Murdered after the defeat of his forces in the Battle of Henry VI [L] 1470-?! Tewkesbury. His son and heir, Edward Prince of Wales, was also killed. Died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving as his heir 1471-83 Edward IV [Y] the 13-year-old Edward V. Disappeared in the Tower of London and probably murdered, along with his brother Richard, on the orders of Edward V(Y] 1483 his uncle and protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who succeeded him on the throne. Defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard III [Y] 1483-85 Succeeded on the throne by his successful adversary Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. •t *(L]= Lancaster [Y)= York / Sence Brook RICHARD King Dick's Hole ao^_ 00/ g •%°^ '"^. 6'^ Atterton '°»•„>••0' 4<^ Bloody. -

Inspiration from Kick@Ss Tudor Women Day One: Lady Margaret Beaufort

Inspiration from Kick@ss Tudor Women Day One: Lady Margaret Beaufort Hello and welcome to Day One of the Inspiration from Kickass Tudor Women minicourse. My name is Heather Teysko, and for those of you who don’t know me, I started a podcast called the Renaissance English History Podcast in 2009, and have been podcasting for the past eight years about my favorite time period in history. I also lead history tours to England, design gorgeous planners and journals inspired by Tudor history, and do courses on podcasting. I live in Spain with my husband and three year old daughter, and before that I lived in London, New York, Los Angeles, and I’m originally from Amish Country Pennsylvania. So that’s a little bit about who I am. As this course goes on, I want to know more about who you are, about what inspires you about history, and what you get out of learning about it. My first job in high school was as a student docent at a local home built by a Revolutionary War general, Rock Ford Plantation in Lancaster PA, owned by General Edward Hand, adjutant general to Washington. I spent five years there, and during that time I got to know Edward Hand really well. I handled his medical equipment, I touched his books, and I got to know him really well. But I really didn’t know much about his wife. And, as someone who loved history, but also was interested in women’s history, that really bugged me. There are a lot of reasons why women don’t make it into the historical narrative. -

AN Tacht UM ATHCHÓIRIÚ an DLÍ REACHTÚIL 2007

———————— Uimhir 28 de 2007 ———————— AN tACHT UM ATHCHÓIRIÚ AN DLÍ REACHTÚIL 2007 [An tiontú oifigiúil] ———————— RIAR NA nALT Alt 1. Mínithe. 2. Athchóiriú an dlí reachtúil i gcoitinne, aisghairm agus cosaint. 3. Aisghairm shonrach. 4. Gearrtheidil a shannadh. 5. Leasú ar an Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Leasú ar an Acht um Ghearrtheidil 1962. 7. Leasuithe ilghnéitheacha ar ghearrtheidil iar-1800. 8. Fianaise ar sheanreachtanna áirithe, etc. 9. Cosaint. 10. Gearrtheideal agus comhlua. SCEIDEAL 1 Reachtanna a Choimeádtar CUID 1 Reachtanna Éireannacha Réamh-Aontachta 1169 go 1800 CUID 2 Reachtanna Shasana 1066 go 1706 CUID 3 Reachtanna na Breataine Móire 1707 go 1800 CUID 4 Reachtanna Ríocht Aontaithe na Breataine Móire agus na hÉireann 1801 go 1922 1 [Uimh. 28.]An tAcht um Athchóiriú an Dlí [2007.] Reachtúil 2007. SCEIDEAL 2 Reachtanna a Aisghairtear go Sonrach CUID 1 Reachtanna Éireannacha Réamh-Aontachta 1169 go 1800 CUID 2 Reachtanna Shasana 1066 go 1706 CUID 3 Reachtanna na Breataine Móire 1707 go 1800 CUID 4 Reachtanna Ríocht Aontaithe na Breataine Móire agus na hÉireann 1801 go 1922 ———————— 2 [2007.]An tAcht um Athchóiriú an Dlí [Uimh. 28.] Reachtúil 2007. Na hAchtanna dá dTagraítear Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c.2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. -

Richard III and the Wars of the Roses: a Teaching Unit

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2021 Constructing History: Richard III and the Wars of the Roses: A Teaching Unit Lawson Hammock Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Hammock, Lawson, "Constructing History: Richard III and the Wars of the Roses: A Teaching Unit" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 621. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/621 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Constructing History Lawson Garrett Hammock Richard III and the Wars of the Roses: A Teaching Unit The historical life and times of Richard III of England (1452-1485) presents an especially vivid demonstration of the idea that history is constructed. Both villainized and venerated by his contemporaries, Richard has also run the gamut through modern historians’ portrayals, which brings some query as to their historiological methods. This teaching unit is designed to introduce high school history students to some key concepts of artifact/document analysis. Its four activities allow students to discover for themselves the historical disjunctions that can occur between competing histories. Another reason Richard makes for a wonderful subject is the excitement, the drama, the mystery, and the intrigue surrounding his persona. -

Usurpation, Propaganda and State-Influenced History in Fifteenth-Century England

"Winning the People's Voice": Usurpation, Propaganda and State-influenced History in Fifteenth-Century England. By Andrew Broertjes, B.A (Hons) This thesis is presented for the Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia Humanities History 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Introduction p. 1 Chapter One: Political Preconditions: Pretenders, Usurpation and International Relations 1398-1509. p. 19 Chapter Two: "The People", Parliament and Public Revolt: the Construction of the Domestic Audience. p. 63 Chapter Three: Kingship, Good Government and Nationalism: Contemporary Attitudes and Beliefs. p. 88 Chapter Four: Justifying Usurpation: Propaganda and Claiming the Throne. p. 117 Chapter Five: Promoting Kingship: State Propaganda and Royal Policy. p. 146 Chapter Six: A Public Relations War? Propaganda and Counter-Propaganda 1400-1509 p. 188 Chapter Seven: Propagandistic Messages: Themes and Critiques. p. 222 Chapter Eight: Rewriting the Fifteenth Century: English Kings and State Influenced History. p. 244 Conclusion p. 298 Bibliography p. 303 Acknowledgements The task of writing a doctoral thesis can be at times overwhelming. The present work would not be possible without the support and assistance of the following people. Firstly, to my primary supervisor, Professor Philippa Maddern, whose erudite commentary, willingness to listen and general support since my undergraduate days has been both welcome and beneficial to my intellectual growth. Also to my secondary supervisor, Associate Professor Ernie Jones, whose willingness to read and comment on vast quantities of work in such a short space of time has been an amazing assistance to the writing of this thesis. Thanks are also owed to my reading group, and their incisive commentary on various chapters. -

Who Was Perkin Warbeck?

Ricardian Bulletin Summer 2005 Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Society News and Notices 4 Be Prepared 5 Media Retrospective 8 Stratford St Mary Church, Suffolk 10 News and Reviews 15 The Nature of Research 19 The Man Himself 22 The Debate: Who Was Perkin Warbeck? 27 King Richard the Third by Keith Dockray 29 The French Connection by David Johnson 30 Thomas Stafford: Sixteenth Century Yorkist Rebel by Stephen Lark 32 Logge Notes and Queries: What did a monk spend his money on? by L. Wynne-Davies 36 Correspondence 42 The Barton Library 44 Book Review 46 Booklist 48 Letter from America 50 Report on Society Events 54 Future Society Events 57 Branches and Groups Contacts 59 Branches and Groups 63 New Members 64 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. Articles and correspondence regarding the Bulletin Debate should be sent to Peter Hammond and all other contributions to Elizabeth Nokes. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of the The Ricardian and The Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. For contact details see back inside cover of the Bulletin The Ricardian Bulletin is produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee, General Editor Elizabeth Nokes and printed by St Edmundsbury Press. © Richard III Society, 2005 1 From the Chairman Those of you who were in Cambridge recently for the Society’s Triennial Conference will have had the opportunity to view some documents contemporary with King Richard that in all proba- bility have not been unfolded and looked at by anyone for over five hundred years. -

A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII

North Alabama Historical Review Volume 4 North Alabama Historical Review, Volume 4, 2014 Article 3 2014 To Keep His Subjects Low: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII John Clinton Harris University of North Alabama Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.una.edu/nahr Part of the European History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Harris, J. C. (2014). To Keep His Subjects Low: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII. North Alabama Historical Review, 4 (1). Retrieved from https://ir.una.edu/nahr/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNA Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Alabama Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNA Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To Keep His Subjects Low: A Machiavellian Interpretation of Henry VII John Clinton Harris When Henry Tudor became Henry VII on August 22, 1485, following his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field, many believed the anarchic course of English politics would continue unabated. The Wars of the Roses had gone on for thirty years, a period so long that intrigue, murder, and military force were now common political tools. Furthermore, there was no outward indication that Bosworth would be the last great political upheaval in the conflict; the new king was a twenty-eight year old former exile to the French court who had asserted his royal claim with nothing more than what his rival Richard III sneeringly called “a nomber of beggarly Britons and faynte harted Frenchmen.”1 The victory had only been achieved due to the fractured and distrustful state of English politics, and many, commoner and noble alike, probably wondered how long the young upstart would last before he was killed and replaced after sitting upon a bloody throne of his own.