Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

Weltenfern a Commented Selection of Some of My Works Containing 149 Originals

Weltenfern A commented selection of some of my works containing 149 originals by Siegfried Hornecker Dedicated to the memory of Dan Meinking and Milan Velimirovi ć who both encouraged me to write a book! Weltenfern : German for other-worldly , literally distant from the world , describing a person’s attitude In the opinion of the author the perfect state of mind to compose chess problems. - 1 - Index 1 – Weltenfern 2 – Index 3 – Legal Information 4 – Preface 6 – 20 ideas and themes 6 – Chapter One: A first walk in the park 8 – Chapter Two: Schachstrategie 9 – Chapter Three: An anticipated study 11 – Chapter Four: Sleepless nights, or how pain was turned into beauty 13 – Chapter Five: Knightmares 15 – Chapter Six: Saavedra 17 – Chapter Seven: Volpert, Zatulovskaya and an incredible pawn endgame 21 – Chapter Eight: My home is my castle, but I can’t castle 27 – Intermezzo: Orthodox problems 31 – Chapter Nine: Cooperation 35 – Chapter Ten: Flourish, Knightingale 38 – Chapter Eleven: Endgames 42 – Chapter Twelve: MatPlus 53 – Chapter 13: Problem Paradise and NONA 56 – Chapter 14: Knight Rush 62 – Chapter 15: An idea of symmetry and an Indian mystery 67 – Information: Logic and purity of aim (economy of aim) 72 – Chapter 16: Make the piece go away 77 – Chapter 17: Failure of the attack and the romantic chess as we knew it 82 – Chapter 18: Positional draw (what is it, anyway?) 86 – Chapter 19: Battle for the promotion 91 – Chapter 20: Book Ends 93 – Dessert: Heterodox problems 97 – Appendix: The simple things in life 148 – Epilogue 149 – Thanks 150 – Author index 152 – Bibliography 154 – License - 2 - Legal Information Partial reprint only with permission. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Dvoretsky Lessons 12

The Instructor Tragicomedies in Pawn Endgames “Pawn endgames are rare birds in practice. Players avoid them, because they do not like them, because they do not understand them. It’s certainly no secret that pawn endings are ‘terra incognita’ - even for many masters, right up to the level of grandmasters and world champions.” N. Grigoriev Herewith, I offer proof that these words, spoken by a famous expert on pawn endings, are true. Without commentary, I give below the final moves of some actual games, and offer the readers the chance to comment on them, to uncover all the mistakes committed by both players. The endgames you will be dealing with here are not all that difficult; but still, the players on both sides have The provided you with plenty of opportunities for critical commentary. 1...Kf8 2. Qf5+ Qxf5 3. gf Kg7 4. c4 f3 5. h6+ Kxh6 6. c5 dc 7. f6 Kg6 Instructor White resigned. Mark Dvoretsky 1...g5 2. Kf3 Kd5 3. c6 Kd6 4. Ke4 a6 5. ba Kxc6 6. Kf3 Kb6 7. h4 gh 8. Kg4 Kxa6 9. Kxh4 Kb6 10. Kg4 Kc6 11. h4 Kd6. White resigned. file:///C|/Cafe/Dvoretsky/dvoretsky.htm (1 of 9) [9/11/2001 7:09:02 AM] The Instructor 1. Kh7 Kf7 2. Kh8 Kf8 3. g5. Black resigned. 1. Kg5 Kf8 2. Kxf5 Kf7 3. Kg4 Kf6 4. Kf4 Kf7 5. Kf5 Ke7 6. Ke5 Kf7 7. Kd6 Kf6 8. Kd7 Kf7 9. h6 Kg6 10. f4 Kf7 11. f5 Kf6 Drawn Gazic - Petursson European Junior Championship, Groningen 1978/79 The draw is obvious after 1...Kh8! Black mistakenly allowed the trade of queens. -

Chess Endgame News

Chess Endgame News Article Published Version Haworth, G. (2014) Chess Endgame News. ICGA Journal, 37 (3). pp. 166-168. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38987/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 166 ICGA Journal September 2014 CHESS ENDGAME NEWS G.McC. Haworth1 Reading, UK This note investigates the recently revived proposal that the stalemated side should lose, and comments further on the information provided by the FRITZ14 interface to Ronald de Man’s DTZ50 endgame tables (EGTs). Tables 1 and 2 list relevant positions: data files (Haworth, 2014b) provide chess-line sources and annotation. Pos.w-b Endgame FEN Notes g1 3-2 KBPKP 8/5KBk/8/8/p7/P7/8/8 b - - 34 124 Korchnoi - Karpov, WCC.5 (1978) g2 3-3 KPPKPP 8/6p1/5p2/5P1K/4k2P/8/8/8 b - - 2 65 Anand - Kramnik, WCC.5 (2007) 65. … Kxf5 g3 3-2 KRKRB 5r2/8/8/8/8/3kb3/3R4/3K4 b - - 94 109 Carlsen - van Wely, Corus (2007) 109. … Bxd2 == g4 7-7 KQR..KQR.. 2Q5/5Rpk/8/1p2p2p/1P2Pn1P/5Pq1/4r3/7K w Evans - Reshevsky, USC (1963), 49. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Hhdbiv.Nl for Ordering Details

see website www.hhdbiv.nl for ordering details. The world's largest endgame study database - edition 4 (HHdbIV) Introduction The fourth edition of the famous Harold van der Heijden endgame study database (HHdbIV) is available now. The new edition not only has more than eight thousand extra studies, but also the solutions of tens of thousands of studies have been corrected or updated. It is by far the most comprehensive collection of endgame studies available. Chess players can benefit from endgame studies by trying to solve them. This trains both one's calculation ability and tactical performance in the endgame. For the endgame study enthusiast, either admirer, cook hunter, composer or tourney judge HHdbIV is indispensable. Apart from the new studies the new version has many improvements over the previous edition. www.hhdbiv.nl What is an endgame study? An endgame study is a chess position presented as a puzzle with the stipulation White wins, or White draws, and has a unique solution. Although it looks like a game fragment, an endgame study has been composed. A good endgame study should have an entertaining solution with surprising moves or beautiful combinations that baffle chess players. It is also fun to try and solve endgame studies for both beginners and world class grandmasters as difficulty ranges from simple to very difficult. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endgame_study Chess Players "Studies are a very important part of the chess culture. I use a lot of studies for the training of imagination and calculations. The study database of Harold van der Heijden is the best source if you are looking for the less known positions". -

Sample Pages

Dvoretsky’s Analytical Manual by Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Karsten Müller 2013 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Dvoretsky’s Analytical Manual © Copyright 2008, 2013 Mark Dvoretsky All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. ISBN: 978-1-936490-74-5 First Edition 2008 Second Edition 2013 Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover design by Janel Lowrance Translated from the Russian by Jim Marfia Photograph of Mark Dvoretsky by Carl G. Russell Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Foreword 4 Introduction 5 Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 10 Part 1 Immersion in the Position 11 Chapter 1 Combinative Fireworks 12 Chapter 2 Chess Botany – The Trunk 25 Chapter 3 Chess Botany – The Shrub 32 Chapter 4 Chess Botany – Variational Debris 38 Chapter 5 Irrational Complications 49 Chapter 6 Surprises in Calculating Variations 61 Chapter 7 More Surprises in Calculating Variations 69 Part 2 Analyzing the Endgame 85 Chapter 8 Two Computer Analyses 86 Chapter 9 Zwischenzugs in the Endgame 93 Chapter 10 Play like a Computer 98 Chapter 11 Challenging Studies 106 Chapter 12 Studies for Practical -

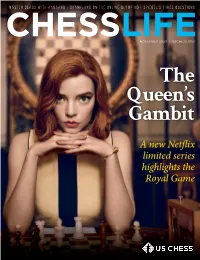

The Queen's Gambit

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

The World's Largest Endgame Study Database - Edition 5 (Hhdbv)

see website www.hhdbv.nl for ordering details. The world's largest endgame study database - edition 5 (HHdbV) Introduction The fifth edition of the famous Harold van der Heijden endgame study database (HHdbV) is available now. The new edition, with 85,619 studies not only has more than 9,000 new studies in comparison with HHdbIV, but also the solutions of tens of thousands of studies have been corrected or updated. It is by far the most comprehensive collection of endgame studies available. Chess players can benefit from endgame studies by trying to solve them. This trains both one's calculation ability and tactical performance in the endgame. For the endgame study enthusiast, either admirer, cook hunter, composer or tourney judge HHdbV is indispensable. Apart from the new studies the new version has many improvements over the previous editions. www.hhdbv.nl What is an endgame study? An endgame study is a chess position presented as a puzzle with the stipulation White wins, or White draws, and has a unique solution. Although it looks like a game fragment, an endgame study has been composed. A good endgame study should have an entertaining solution with surprising moves or beautiful combinations that baffle chess players. It is also fun to try and solve endgame studies for both beginners and world class grandmasters as difficulty ranges from simple to very difficult. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endgame_study Software The database is in PGN-format. This is a standard chess database format and can be accessed by commercial chess database programs (like ChessBase, Chess Assistant), commercial chess playing software (Fritz, Rybka, Shredder, etc.) and many freeware programs (e.g. -

Dvoretsky's Endgame Manual

Dvoretsky’s Endgame Manual Mark Dvoretsky Foreword by Artur Yusupov Preface by Jacob Aagaard 2003 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 Table of Contents Foreword 6 Preface 7 From the Author 8 Other Signs, Symbols, and Abbreviations 12 Chapter 1 PAWN ENDGAMES 13 Key Squares 13 Corresponding Squares 14 Opposition 14 Mined Squares 18 Triangulation 20 Other Cases of Correspondence 22 King vs. Passed Pawns 24 The Rule of the Square 24 Réti’s Idea 25 The Floating Square 27 Three Connected Pawns 28 Queen vs. Pawns 29 Knight or Center Pawn 29 Rook or Bishop’s Pawn 30 Pawn Races 32 The Active King 34 Zugzwang 34 Widening the Beachhead 35 The King Routes 37 Zigzag 37 The Pendulum 38 Shouldering 38 Breakthrough 40 The Outside Passed Pawn 44 Two Rook’s Pawns with an Extra Pawn on the Opposite Wing 45 The Protected Passed Pawn 50 Two Pawns to One 50 Multi-Pawn Endgames 50 Undermining 53 Two Connected Passed Pawns 54 Stalemate 55 The Stalemate Refuge 55 “Semi-Stalemate” 56 Reserve Tempi 57 Exploiting Reserve Tempi 57 Steinitz’s Rule 59 The g- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 60 The f- and h-Pawns vs. h-Pawn 62 Both Sides have Reserve Tempi 65 Chapter 2 KNIGHT VS. PAWNS 67 1 King in the Corner 67 Mate 67 Drawn Positions 67 Knight vs. Rook Pawn 68 The Knight Defends the Pawn 70 Chapter 3 KNIGHT ENDGAMES 74 The Deflecting Knight Sacrifice 74 Botvinnik’s Formula 75 Pawns on the Same Side 79 Chapter 4 BISHOP VS. -

One of the First Things That Strikes the Endgame Study Enthusiast Is the Fact That There Have Been No Great British Composers

EG OCTOBER, 1965 One of the first things that strikes the endgame study enthusiast is the fact that there have been no great British composers. Certainly the British study has had its inspired moments, such as the famous study by Joseph which our first Tourney commemorates, but never has there been a plethora of fine composers, or even one who has really stood out from the rest. On the other hand, British problems have always been amongst the best, which to my mind indicates that chess composition is in our blood; furthermore, there is evidence that there is no lack of future problem talent at the present time. The reason for this lies, I am sure, in the lack of encouragement for composers and general interest among the chess public. It is to be hoped that the Chess Endgame Study Circle and its organ EG will provide the necessary stimulus for the budding composer by (a) keeping him in touch with recent developments (b) providing material for the improvement of his techniques (c) giving him the chance to display his best work prominently and (d) by holding regular meetings to stimulate discussion and allow for lectures by leading composers. More generally, the mere existence of E G should increase interest among chessplayers; by holding tourneys, by acting as a source book, by encouraging discussion, it should cause chess columnists and others to devote more time and space to studies. There is a place for the purely aesthetic in the average chess player's world, provided that it is intelligently presented.