A Role of Microtubules in Oligodendrocyte Differentiation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Specification of Optic Nerve Oligodendrocyte Precursors by Retinal Ganglion Cell Axons

The Journal of Neuroscience, July 19, 2006 • 26(29):7619–7628 • 7619 Cellular/Molecular Specification of Optic Nerve Oligodendrocyte Precursors by Retinal Ganglion Cell Axons Limin Gao and Robert H. Miller Department of Neurosciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio 44106 Cell fate commitment in the developing CNS frequently depends on localized cell–cell interactions. In the avian visual system the optic nerve oligodendrocytes are derived from founder cells located at the floor of the third ventricle. Here we show that the induction of these founder cells is directly dependent on signaling from the retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons. The appearance of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) correlates with the projection of RGC axons, and early eye removal dramatically reduces the number of OPCs. In vitro signaling from retinal neurites induces OPCs in responsive tissue. Retinal axon induction of OPCs is dependent on sonic hedgehog (Shh) andneuregulinsignaling,andtheinhibitionofeithersignalreducesOPCinductioninvivoandinvitro.ThedependenceofOPCsonretinal axonal cues appears to be a common phenomenon, because ocular retardation (orJ) mice lacking optic nerve have dramatically reduced OPCs in the midline of the third ventricle. Key words: oligodendrocyte precursors; optic nerve; axon induction; sonic hedgehog; neuregulin; retinal ganglion cells Introduction contributes to the specification of ventral midline cells (Dale et al., During development the oligodendrocytes, the myelinating cells 1997); however, OPCs arise later -

Early Neuronal Processes Interact with Glia to Establish a Scaffold For

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/754416; this version posted August 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Early neuronal processes interact with glia to establish a scaffold for orderly innervation of the cochlea Running Title: Glia and early cochlear wiring N. R. Druckenbrod1, E. B. Hale, O. O. Olukoya, W. E. Shatzer, and L.V. Goodrich* Department of Neurobiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02115 1Current address: Decibel Therapeutics, Boston, Ma, 02215 *correspondence should be addressed to [email protected] Keywords: neuron-glia interactions, axon guidance, spiral ganglion neuron, cochlea Authors’ contributions: This study was conceived of and designed by NRD and LVG. NRD, EBH, OOO, and WES performed experiments and analyzed results. LVG analyzed results and wrote the manuscript. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/754416; this version posted August 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Summary: Although the basic principles of axon guidance are well established, it remains unclear how axons navigate with high fidelity through the complex cellular terrains that are encountered in vivo. To learn more about the cellular strategies underlying axon guidance in vivo, we analyzed the developing cochlea, where spiral ganglion neurons extend processes through a heterogeneous cellular environment to form tonotopically ordered connections with hair cells. -

Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond

cells Review Oligodendrocytes in Development, Myelin Generation and Beyond Sarah Kuhn y, Laura Gritti y, Daniel Crooks and Yvonne Dombrowski * Wellcome-Wolfson Institute for Experimental Medicine, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (L.G.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0044-28-9097-6127 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 7 November 2019; Published: 12 November 2019 Abstract: Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) that are generated from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC). OPC are distributed throughout the CNS and represent a pool of migratory and proliferative adult progenitor cells that can differentiate into oligodendrocytes. The central function of oligodendrocytes is to generate myelin, which is an extended membrane from the cell that wraps tightly around axons. Due to this energy consuming process and the associated high metabolic turnover oligodendrocytes are vulnerable to cytotoxic and excitotoxic factors. Oligodendrocyte pathology is therefore evident in a range of disorders including multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Deceased oligodendrocytes can be replenished from the adult OPC pool and lost myelin can be regenerated during remyelination, which can prevent axonal degeneration and can restore function. Cell population studies have recently identified novel immunomodulatory functions of oligodendrocytes, the implications of which, e.g., for diseases with primary oligodendrocyte pathology, are not yet clear. Here, we review the journey of oligodendrocytes from the embryonic stage to their role in homeostasis and their fate in disease. We will also discuss the most common models used to study oligodendrocytes and describe newly discovered functions of oligodendrocytes. -

Neuregulin 1–Erbb2 Signaling Is Required for the Establishment of Radial Glia and Their Transformation Into Astrocytes in Cerebral Cortex

Neuregulin 1–erbB2 signaling is required for the establishment of radial glia and their transformation into astrocytes in cerebral cortex Ralf S. Schmid*, Barbara McGrath*, Bridget E. Berechid†, Becky Boyles*, Mark Marchionni‡, Nenad Sˇ estan†, and Eva S. Anton*§ *University of North Carolina Neuroscience Center and Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; †Department of Neurobiology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510; and ‡CeNes Pharamceuticals, Inc., Norwood, MA 02062 Communicated by Pasko Rakic, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, January 27, 2003 (received for review December 12, 2002) Radial glial cells and astrocytes function to support the construction mine whether NRG-1-mediated signaling is involved in radial and maintenance, respectively, of the cerebral cortex. However, the glial cell development and differentiation in the cerebral cortex. mechanisms that determine how radial glial cells are established, We show that NRG-1 signaling, involving erbB2, may act in maintained, and transformed into astrocytes in the cerebral cortex are concert with Notch signaling to exert a critical influence in the not well understood. Here, we show that neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) exerts establishment, maintenance, and appropriate transformation of a critical role in the establishment of radial glial cells. Radial glial cell radial glial cells in cerebral cortex. generation is significantly impaired in NRG mutants, and this defect can be rescued by exogenous NRG-1. Down-regulation of expression Materials and Methods and activity of erbB2, a member of the NRG-1 receptor complex, leads Clonal Analysis to Study NRG’s Role in the Initial Establishment of to the transformation of radial glial cells into astrocytes. -

Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS

The Journal of Neuroscience, April 1992, 12(4): 1538-l 547 Pre-Oligodendrocytes from Adult Human CNS Regina C. Armstrong,lJ Henry H. Dorn, l,b Conrad V. Kufta,* Emily Friedman,3 and Monique E. Dubois-Dalcq’ ‘Laboratory of Viral and Molecular Pathogenesis, and %urgical Neurology Branch, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 and 3Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-3246 CNS remyelination and functional recovery often occur after Rapid and efficient neurotransmission is dependent upon the experimental demyelination in adult rodents. This has been electrical insulating capacity of the myelin sheath around axons attributed to the ability of mature oligodendrocytes and/or (reviewed in Ritchie, 1984a,b). Nerve conduction is impaired their precursor cells to divide and regenerate in response after loss of the myelin sheath and results in severe neurological to signals in demyelinating lesions. To determine whether dysfunction in human demyelinating diseases such as multiple oligodendrocyte precursor cells exist in the adult human sclerosis (MS). Remyelination can occur in the CNS of MS CNS, we have cultured white matter from patients under- patients but appears to be limited (Perier and Gregoire, 1965; going partial temporal lobe resection for intractable epilep- Prineas et al., 1984). Studies of acute MS cases have revealed sy. These cultures contained a population of process-bear- that recent demyelinating lesions can exhibit remyelination that ing cells that expressed antigens recognized by the 04 appears to correlate with the generation of new oligodendrocytes monoclonal antibody, but these cells did not express galac- (Prineas et al., 1984; Raine et al., 1988). -

Spinal Nerves, Ganglia, and Nerve Plexus Spinal Nerves

Chapter 13 Spinal Nerves, Ganglia, and Nerve Plexus Spinal Nerves Posterior Spinous process of vertebra Posterior root Deep muscles of back Posterior ramus Spinal cord Transverse process of vertebra Posterior root ganglion Spinal nerve Anterior ramus Meningeal branch Communicating rami Anterior root Vertebral body Sympathetic ganglion Anterior General Anatomy of Nerves and Ganglia • Spinal cord communicates with the rest of the body by way of spinal nerves • nerve = a cordlike organ composed of numerous nerve fibers (axons) bound together by connective tissue – mixed nerves contain both afferent (sensory) and efferent (motor) fibers – composed of thousands of fibers carrying currents in opposite directions Anatomy of a Nerve Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Epineurium Perineurium Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Endoneurium Nerve Rootlets fiber Posterior root Fascicle Posterior root ganglion Anterior Blood root vessels Spinal nerve (b) Copyright by R.G. Kessel and R.H. Kardon, Tissues and Organs: A Text-Atlas of Scanning Electron Microscopy, 1979, W.H. Freeman, All rights reserved Blood vessels Fascicle Epineurium Perineurium Unmyelinated nerve fibers Myelinated nerve fibers (a) Endoneurium Myelin General Anatomy of Nerves and Ganglia • nerves of peripheral nervous system are ensheathed in Schwann cells – forms neurilemma and often a myelin sheath around the axon – external to neurilemma, each fiber is surrounded by -

Spinal Cord Organization

Lecture 4 Spinal Cord Organization The spinal cord . Afferent tract • connects with spinal nerves, through afferent BRAIN neuron & efferent axons in spinal roots; reflex receptor interneuron • communicates with the brain, by means of cell ascending and descending pathways that body form tracts in spinal white matter; and white matter muscle • gives rise to spinal reflexes, pre-determined gray matter Efferent neuron by interneuronal circuits. Spinal Cord Section Gross anatomy of the spinal cord: The spinal cord is a cylinder of CNS. The spinal cord exhibits subtle cervical and lumbar (lumbosacral) enlargements produced by extra neurons in segments that innervate limbs. The region of spinal cord caudal to the lumbar enlargement is conus medullaris. Caudal to this, a terminal filament of (nonfunctional) glial tissue extends into the tail. terminal filament lumbar enlargement conus medullaris cervical enlargement A spinal cord segment = a portion of spinal cord that spinal ganglion gives rise to a pair (right & left) of spinal nerves. Each spinal dorsal nerve is attached to the spinal cord by means of dorsal and spinal ventral roots composed of rootlets. Spinal segments, spinal root (rootlets) nerve roots, and spinal nerves are all identified numerically by th region, e.g., 6 cervical (C6) spinal segment. ventral Sacral and caudal spinal roots (surrounding the conus root medullaris and terminal filament and streaming caudally to (rootlets) reach corresponding intervertebral foramina) collectively constitute the cauda equina. Both the spinal cord (CNS) and spinal roots (PNS) are enveloped by meninges within the vertebral canal. Spinal nerves (which are formed in intervertebral foramina) are covered by connective tissue (epineurium, perineurium, & endoneurium) rather than meninges. -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

Digital Neuroanatomy

DIGITAL NEUROANATOMY LM NEUROHISTOLOGY George R. Leichnetz, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Anatomy & Neurobiology Virginia Commonwealth University 2004 Press the Å and Æ keys on your keyboard to navigate through this lecture There are three morphological types of neurons in the nervous system: unipolar, bipolar, and multipolar. While all three types can be found in the PNS, the CNS only contains multipolar neurons. CNS multipolar neurons vary greatly in morphology: eg. spinal cord motor neurons, pyramidal cells of cerebral cortex, Purkinje cells of cerebellar cortex. The supportive cells of the CNS are neuroglia: astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia. Oligodendrocytes myelinate CNS axons, while Schwann cells myelinate PNS axons. Protoplasmic astrocytes predominate in CNS gray matter, while fibrous astrocytes predominate in CNS white matter. The ventral horn of the spinal cord Lumbar Spinal Cord contains multipolar motor neurons. Dorsal White Horn Matter Gray Matter Ventral Kluver- Horn Barrera Stain (LFB & CV) Cell bodies of motor neurons Dendrite Gray Matter Dendrite Perineuronal H & E oligodendrocyte Stain Nucleus, nucleolus Abundant Nissl substance Dorsal root Dorsal root ganglion Ventral root Gray Matter: contains White Matter: cell bodies of neurons contains x-sections of myelinated axons Multipolar motor neurons Silver Stain of the ventral horn Large multipolar motor neurons of the spinal cord ventral horn: see nucleus, nucleolus, abundant Nissl substance, multiple tapering processes (dendrites). The axon hillock (origin of axon from cell body) lacks Nissl. Nucleus Axon hillock dendrites Nucleolus Nissl substance (RER) Kluver-Barrera Stain (Luxol Fast Blue and Cresyl Violet) Thoracic Spinal Cord The nucleus dorsalis of Clarke, located in the base of the dorsal horn of the thoracic spinal cord, contains multipolar neurons whose nucleus is eccentric and Nissl around the periphery of the cell body (as if it were chromatolytic). -

View Software

TLR4-activated microglia have divergent effects on oligodendrocyte lineage cells DISSERTATION Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University Evan Zachary Goldstein, BA Neuroscience Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Dana McTigue, Advisor Dr. Phillip Popovich Dr. Jonathan Godbout Dr. Courtney DeVries Copyright by Evan Zachary Goldstein 2016 i Abstract Myelin accelerates action potential conduction velocity and provides essential metabolic support for axons. Unfortunately, myelin and myelinating cells are often vulnerable to injury or disease, resulting in myelin damage, which in turn can lead to axon dysfunction, overt pathology and neurological impairment. Inflammation is a common component of CNS trauma and disease, and therefore an active inflammatory response is often considered deleterious to myelin health. While inflammation can certainly damage myelin, inflammatory processes also benefit oligodendrocyte (OL) lineage progression and myelin repair. Consistent with the divergent nature of inflammation, intraspinal toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation, an innate immune pathway, kills OL lineage cells, but also initiates oligodendrogenesis. Soluble factors produced by TLR4-activated microglia can reproduce these effects in vitro, however the exact factors are unknown. To determine what microglial factors might contribute to TLR4-induced OL loss and oligodendrogenesis, mRNA of factors known to affect OL lineage cells was quantified in TLR4-activated microglia and spinal cords (chapter 2). Results indicate that TLR4-activated microglia transcribe numerous factors that induce OL loss, OL progenitor cell (OPC) proliferation and OPC differentiation. However, some factors upregulated after intraspinal TLR4 activation were not ii upregulated by microglia, suggesting that other cell types contribute to transcriptional changes in vivo. -

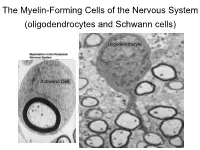

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Gathering at the Nodes

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS GLIA Gathering at the nodes Saltatory conduction — the process by which that are found at the nodes of Ranvier, where action potentials propagate along myelinated they interact with Na+ channels. When the nerves — depends on the fact that voltage- authors either disrupted the localization of gated Na+ channels form clusters at the nodes gliomedin by using a soluble fusion protein of Ranvier, between sections of the myelin that contained the extracellular domain of sheath. New findings from Eshed et al. show neurofascin, or used RNA interference to that Schwann cells produce a protein called suppress the expression of gliomedin, the gliomedin, and that this is responsible for characteristic clustering of Na+ channels at the clustering of these channels. the nodes of Ranvier did not occur. The formation of the nodes of Ranvier is Aggregation of the domain of gliomedin specified by the myelinating cells, not the that binds neurofascin and NrCAM on the axons, and an important component of this surface of purified neurons also caused process in the peripheral nervous system the clustering of neurofascin, Na+ channels is the extension of microvilli by Schwann and other nodal proteins. These findings cells. These microvilli contact the axons at support a model in which gliomedin on the nodes, and it is here that the Schwann References and links Schwann cell microvilli binds to neurofascin ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Eshed, Y. et al. Gliomedin cells express the newly discovered protein and NrCAM on axons, causing them to mediates Schwann cell–axon interaction and the molecular gliomedin. cluster at the nodes of Ranvier, and leading assembly of the nodes of Ranvier.