Cantomap: a Hong Kong Cantonese Maptask Corpus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese (Chin) 1

CHINESE (CHIN) 1 CHIN 242. Chinese Qin Music. 3 Credits. CHINESE (CHIN) This course offers students an opportunity to learn the aesthetics, culture, and history of qin, and study the music through learning the CHIN 101. Elementary Chinese I. 4 Credits. beginning levels of qin pieces. Introduction to Mandarin Chinese, focusing on pronunciation, simple Gen Ed: VP, BN, EE- Performing Arts. conversation, and basic grammar. Reading and writing Chinese Grading status: Letter grade. characters are also taught. Writing Chinese characters is required. Four CHIN 244. Introduction to Modern Chinese Culture through Cinema. 3 hours per week. Students may not receive credit for both CHIN 101 or Credits. CHIN 102 and CHIN 111. This course uses select feature and documentary films, supplemented by Gen Ed: FL. texts of critical and creative literature, to introduce students to a broad Grading status: Letter grade. overview of modern China since the mid-19th century, focusing on the CHIN 102. Elementary Chinese II. 4 Credits. major events that have shaped a turbulent course of decline, revolution, Continued training in listening, speaking, reading, and writing on everyday and resurgence. topics. Writing Chinese characters is required. Four hours per week. Gen Ed: VP, BN. Students may not receive credit for both CHIN 101 or CHIN 102 and Grading status: Letter grade. CHIN 111. CHIN 252. Introduction to Chinese Culture through Narrative. 3 Credits. Requisites: Prerequisite, CHIN 101. This course shows how Chinese historical legends define and transmit Gen Ed: FL. the values, concepts, figures of speech, and modes of behavior that Grading status: Letter grade. constitute Chinese culture. -

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-Accented English: a Phonetic Comparison

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp. 724-738, September 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1105.07 Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-accented English: A Phonetic Comparison Yunyun Ran School of Foreign Languages, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, 333 Long Teng Road, Shanghai 201620, China Jeroen van de Weijer School of Foreign Languages, Shenzhen University, 3688 Nan Hai Avenue, Shenzhen 518060, China Marjoleine Sloos Fryske Akademy (KNAW), Doelestrjitte 8, 8911 DX Leeuwarden, The Netherlands Abstract—Hong Kong English is to a certain extent a standardized English variety spoken in a bilingual (English-Cantonese) context. In this article we compare this (native) variety with English as a foreign language spoken by other Cantonese speakers, viz. learners of English in Guangzhou (mainland China). We examine whether the notion of standardization is relevant for intonation in this case and thus whether Hong Kong English is different from Cantonese English in a wider perspective, or whether it is justified to treat Hong Kong English and Cantonese English as the same variety (as far as intonation is concerned). We present a comparison between intonational contours of different sentence types in the two varieties, and show that they are very similar. This shows that, in this respect, a learned foreign-language variety can resemble a native variety to a great extent. Index Terms—Hong Kong English, Cantonese-accented English, intonation I. INTRODUCTION Cantonese English may either refer to Hong Kong English (HKE), or to a broader variety of English spoken in the Cantonese-speaking area, including Guangzhou (Wong et al. -

Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-Born Chinese Amy Wong New York University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 13 2007 Article 17 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAV 35 10-1-2007 Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-born Chinese Amy Wong New York University This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol13/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-born Chinese This conference paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: http://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/ vol13/iss2/17 Two Vernacular Features in the English of Four American-Born Chinese in New York City* Amy Wong 1 Introduction Variationist sociolinguistics has largely overlooked the English of Chinese Americans, sometimes because many of them spoke English non-natively. However, the number of Chinese immigrants has grown over the last 40 years, in part as a consequence of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act that repealed the severe immigration restrictions established by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (García 1997). The 1965 act led to an increase in the number of America Born Chinese (ABC) who, as a result of being immersed in the American educational system that “urges inevitable shift to English” (Wong 1988:109), have grown up speaking English natively. Tsang and Wing even assert that “the English verbal performance of native-born Chinese Americans is no different from that of whites” (1985:12, cited in Wong 1988:210), an assertion that requires closer examination. -

Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: Morphology and Syntax*

Breaking Down the Barriers, 785-816 2013-1-050-037-000234-1 Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: * Morphology and Syntax Hilary Chappell (曹茜蕾) EHESS In Chinese languages, when a direct object occurs in a non-canonical position preceding the main verb, this SOV structure can be morphologically marked by a preposition whose source comes largely from verbs or deverbal prepositions. For example, markers such as kā 共 in Southern Min are ultimately derived from the verb ‘to accompany’, pau11 幫 in many Huizhou and Wu dialects is derived from the verb ‘to help’ and bǎ 把 from the verb ‘to hold’ in standard Mandarin and the Jin dialects. In general, these markers are used to highlight an explicit change of state affecting a referential object, located in this preverbal position. This analysis sets out to address the issue of diversity in such object-marking constructions in order to examine the question of whether areal patterns exist within Sinitic languages on the basis of the main lexical fields of the object markers, if not the construction types. The possibility of establishing four major linguistic zones in China is thus explored with respect to grammaticalization pathways. Key words: typology, grammaticalization, object marking, disposal constructions, linguistic zones 1. Background to the issue In the case of transitive verbs, it is uncontroversial to state that a common word order in Sinitic languages is for direct objects to follow the main verb without any overt morphological marking: * This is a “cross-straits” paper as earlier versions were presented in turn at both the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, during the joint 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics and 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics, held in Taipei in May 25-29, 2006 and also at an invited seminar at the Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing on 23rd October 2006. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

Download Our Latest Allegravita Backgrounder Booklet Here (PDF)

Name: Allegravita is an award-winning, multi- disciplinary public relations and strategic communications agency focused on supporting international clients in the China region and taking Chinese clients to the world. We were voted China's most entrepreneurial company by the Australian Chambers of ABOUT ALLEGRAVITA Commerce in China in 2008. Allegravita is a boutique global agency A PORTFOLIO OF SERVICES TO BORN IN CHINA, with personnel and offices in Beijing, HELP YOU SUCCEED IN CHINA EFFECTIVE WORLDWIDE Guangzhou, Kunming, Hong Kong, Public Relations for proactive and Although our focus is on the China New York City and San Francisco. Since reactive messaging. region, our services are very effective 2003 we have provided high-quality Marketing and Communications in markets worldwide, with proven PR, marketing and corporate advisory Collateral to present your messages outcomes. Allegravita works within services with a special focus on achiev- with excellent credibility. a highly-accountable and disciplined ing excellent results for international Media Relations & Media Training Western management style, executing clients in the China region and in Chi- to insert your messages into Chinese the highest quality of work for our nese speaking markets worldwide, and and international media in the most clients, which we deliver with agility, international results for our Chinese compelling way possible. flexibility, creativity and cultural savvy. clients. Corporate Identity localization to Allegravita is an ethnically diverse, We incorporate expert public relations communicate your brand values and multi-cultural team of professionals abilities with a firm grasp of contempo- benefits to Chinese markets, and for of different cultural heritages. What rary China-region marketplaces to help Chinese clients, to international inves- we share in common is our passion for our clients communicate effectively, tors and influencers. -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Cantonese As

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Cantonese as Spoken in the Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces of China 1. Dialects The name "Cantonese" is used either for all of the language varieties spoken in specific regions in the Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces of China and Hong Kong (i.e., the Yue dialects of Chinese), or as one particular variety referred to as the "Guangfu group" (Bauer & Benedict 1997). In instances where Cantonese is described as 'Cantonese "proper"' (i.e. used in the narrower sense), it refers to a variety of Cantonese that is spoken in the capital cities Guangzhou and Nanning, as well as in Hong Kong and Macau. This database includes Cantonese as spoken in the Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces of China only (i.e. not in Hong Kong); five dialect groups have been defined for Cantonese (see the following table)1. Three general principles have been used in defining these dialect groupings: (i) phonological variation, (ii) geographical variation, and (iii) lexical variation. With relation to phonological variation, although Cantonese is spoken in all of the regions listed in the table, there are differences in pronunciation. Differences in geographic locations also correlate with variations in lexical choice. Cultural differences are also correlated with linguistic differences, particularly in lexical choices. Area Cities (examples) Central Guangzhou, Conghua, Fogang (Shijiao), Guangdong Longmen, Zengcheng, Huaxian Group Northern Shaoguan, Qijiang, Lian Xian, Liannan, Guangdong Yangshan, Yingde, Taiping Group Northern -

Cifu: a Frequency Lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 3069–3077 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Cifu: a frequency lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese Regine Lai, Grégoire Winterstein The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Université du Québec à Montréal Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, Département de Linguistique [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper introduces Cifu, a lexical database for Hong Kong Cantonese (HKC) that offers phonological and orthographic information, frequency measures, and lexical neighborhood information for lexical items in HKC. The resource can be used for NLP applications and the design and analysis of psycholinguistic experiments on HKC. We elaborate on the characteristics and challenges specific to HKC that were relevant in the design of Cifu. This includes lexical, orthographic and phonological aspects of HKC, word segmentation issues, the place of HKC in written media, and the availability of data. We discuss the measure of Neighborhood Density (ND), highlighting how the analytic nature of Cantonese and its writing system affect that measure. We justify using six different variations of ND, based on the possibility of inserting or deleting phonemes when searching for neighbors and on the choice of data for retrieving frequencies. Statistics about the four genres (written, adult spoken, children spoken and child-directed) within the dataset are discussed. We find that the lexical diversity of the child-directed speech genre is particularly low, compared to a size-matched written corpus. The correlations of word frequencies of different genres are all high, but in general decrease as word length increases. -

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港港港語語語語語語料料料庫庫庫

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港nn;;;;;;$$$庫庫庫 ã 180,000-word corpus of Cantonese Speech ã 52 spontaneous conversations ã 42 radio programmes ã Transcribed (UTF-8); Transliterated Segmented; POS tagged ã English translation described in paper, not in downloadable corpus ã Available directly for download (no explicit license) http://compling.hss.ntu.edu.sg/hkcancor/ ã Produced by Luke Kang Kwong and ML Wong Francis Bond <[email protected]> HG3051 lab2 1 Creation ã 30 hours of recordings (March 1997 — August 1998) ã Native speakers of Cantonese ã ordinary settings with family members, friends and colleagues talking with each other freely on everyday topics such as current affairs, work and study, and personal hobbies ã Some parts selected 2 Meta-Data/Annotation ã Meta-Data Tape number (of recording); Date of recording Number of Speakers; List of Speakers (Code-Sex-Age-Origin) (e.g. A-M-22-HK says A is a 22-year-old male speaker from Hong Kong) ã Annotation Each Utterance has the speaker code Utterances are segmented, POS tagged and transliterated Ç%h/d/ge3i1bun2soeng6/ 2個/r/ni1go3/ze ... ã The whole corpus is wrapped in xml (but not very well) 3 Usage ã Used to examine the uses of the frequently used sentence final particles woˇ and boˇ in the 1990s in Hong Kong Cantonese by examining speech data. ã Question: are woˇ (喎) and boˇ (S) variant forms? ã Answer: No “[. ] the two SFPs carry and serve different meanings and functions in modern Hong Kong Cantonese, and thus they are not exactly the same particles and not interchangeable as previously assumed.” (Leung, 2010, p21) ã Also used as a corpus in the PyCantonese Project: Working with Cantonese corpus data using Python, by Jackson L. -

Navigating the Challenges of Data Quality and Recognition in China Global-Z China Experience

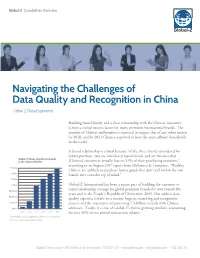

Global-Z Capabilities Overview Navigating the Challenges of Data Quality and Recognition in China Global-Z China Experience Building brand loyalty and a close relationship with the Chinese consumer is now a critical success factor for many premium international brands. The number of Chinese millionaires is expected to surpass that of any other nation by 2018, and by 2021 China is expected to have the most affluent households in the world. A brand relationship is critical because “of the three brands considered for luxury purchase, two are considered top-of-mind, and are the ones that Global-Z Shows Significant Growth in the Chinese Market (Chinese) consumers actually buy on 93% of their purchasing occasions,” according to an August 2017 report from McKinsey & Company. “Wealthy 7.5 Billion Chinese are unlikely to purchase luxury goods that don’t fall within the two 5 Billion brands they consider top of mind.” 2.5 Billion 1 Billion Global-Z International has been a major part of building the customer to 750 Million brand relationship strategy for global premium brands for over twenty-five years and in the People’s Republic of China since 2003. Our address data 500 Million quality expertise is built on a mature hygiene, matching and recognition 50 Million process and the experience of processing 7.5-billion records with Chinese 5 Million addresses. Today, it is one of Global-Z’s fastest growing markets, accounting 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 for over 50% of our annual transaction volume. Cumulative cleansing transactions processed on Chinese name and address data. -

The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in TESL Department of English 12-2019 The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners Yahui Shi Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/tesl_etds Recommended Citation Shi, Yahui, "The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual Learners" (2019). Culminating Projects in TESL. 17. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/tesl_etds/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in TESL by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effect of Pinyin in Chinese Vocabulary Acquisition with English-Chinese Bilingual learners by Yahui Shi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Thesis Committee: Choonkyong Kim, Chairperson John Madden Zengjun Peng 2 Abstract This study investigates Chinese vocabulary acquisition of Chinese language learners in English-Chinese bilingual contexts; the 20 participants in this study were English native speakers, who were enrolled in a Chinese immersion program in central Minnesota. The study used a matching test, and the test contains seven sets of test items. In each set, there were six Chinese vocabulary words and the English translations of three of them. The six words are listed in one column on the left, and the three translations were in another column on the right.