Gender Representation 1977-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

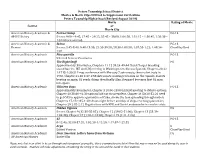

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Leading Actor Benedict Cumberbatch 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Imitation Game Eddie Redmayne 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Theory of Everything Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award Nominee in 2012 Jake Gyllenhaal 2 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 2006: Brokeback Mountain Leading Actor in 2015: Nightcrawler Michael Keaton 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: Birdman Ralph Fiennes 6 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 1994: Schindler’s List Leading Actor in 1997: The English Patient Leading Actor in 2000: The End of The Affair Leading Actor in 2006: The Constant Gardener Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer in 2012: Coriolanus (as Director) Leading Actor in 2015: The Grand Budapest Hotel Leading Actress Amy Adams 5 nominations Supporting Actress in 2009: Doubt Supporting Actress in 2011: The Fighter Supporting Actress in 2013: The Master Leading Actress in 2014: American Hustle Leading Actress in 2015: Big Eyes Felicity Jones 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: The Theory of Everything Julianne Moore 4 nominations Leading Actress in 2000: The End of the Affair Supporting Actress in 2003: The Hours Leading Actress in 2011: The Kids are All Right Leading Actress in 2015: Still Alice Reese Witherspoon 2 nominations / 1 win Leading Actress in 2006: Walk the Line Leading Actress in 2015: Wild Rosamund Pike 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: Gone Girl Supporting Actor Edward Norton 2 nominations Supporting Actor in 1997: Primal Fear Supporting Actor in 2015: Birdman Ethan Hawke 1 nomination Supporting Actor in 2015: Boyhood J. -

Driving Miss Daisy Flame.Indd

Women’s Health CLINIC FEBRUARY 2014 SEASON | YEAR A NEWSLETTER DEDICATED TO GROUPS, ORGANIZATIONS AND FRIENDS OF THE FIRESIDE THEATRE A Hilarious, Heartwarming Must-See FOR OVER THREE DECADES THE FIRESIDE HAS BEEN KNOWN FOR PRODUCING BIG, BRIGHT MUSICAL COMEDIES AND SPECTACULAR MUSICAL REVUES. MUSICAL THEATRE HAS BEEN MY SPECIALTY AND MY PASSION SINCE I SAW MY FIRST BROADWAY MUSICAL AT AGE 6. I TAKE GREAT PRIDE WHENEVER SOMEONE MARVELS AT HOW WE CAN TAKE A BIG BROADWAY MUSICAL AND PUT IT ON OUR SMALL ARENA STAGE WITHOUT LOSING ANY OF ITS WONDER. MUSICALS HAVE BEEN, WITHOUT A DOUBT, THE MAIN DISH ON THE FIRESIDE’S THEATRICAL MENU SINCE WE FIRST OPENED. Then why is it that one of the most I am very excited about directing our popular shows in Fireside history (as well production of this unforgettable play this as in theatrical history) is a three person spring. I have directed DRIVING MISS play about an elderly white woman, her DAISY twice before – once here and aging African American chauffer, and once in a theatre in Ohio and I can her beleaguered middle aged son told honestly say that of all the wonderful simply without a song or a dance in sight. shows I have directed in my 45+ years Is it because we see ourselves and our as a professional director that no other loved ones in this heart-warming tale? Is play has touched my heart more deeply “ Millions of people rank this it because it is hilariously funny without than DAISY. And I am not alone. -

Oscar-Winning 'Slumdog Millionaire:' a Boost for India's Global Image?

ISAS Brief No. 98 – Date: 27 February 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Oscar-winning ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: A Boost for India’s Global Image? Bibek Debroy∗ Culture is difficult to define. This is more so in a large and heterogeneous country like India, where there is no common language and religion. There are sub-cultures within the country. Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’ expression draws on a country’s cross-border cultural influences and is one enunciated with the American context in mind. Almost tautologically, soft power implies the existence of a relatively large country and the term is, therefore, now also being used for China and India. In the Indian case, most instances of practice of soft power are linked to language and literature (including Indians writing in English), music, dance, cuisine, fashion, entertainment and even sport, and there is no denying that this kind of cross-border influence has been increasing over time, with some trigger provided by the diaspora. The film and television industry’s influence is no less important. In the last few years, India has produced the largest number of feature films in the world, with 1,164 films produced in 2007. The United States came second with 453, Japan third with 407 and China fourth with 402. Ticket sales are higher for Bollywood than for Hollywood, though revenue figures are much higher for the latter. Indian film production is usually equated with Hindi-language Bollywood, often described as the largest film-producing centre in the world. -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

Breaking Away- Journey to Platinum Final Report (2011)

BREAKING AWAY: JOURNEY TO PLATINUM BLOOMINGTON PLATINUM BICYCLE TASK FORCE BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA FINAL REPORT: NOVEMBER 30, 2011 Page Intentionally Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................... iii LITTLE 500: PROLOGUE........................................................................iv The Platinum Biking Task Force .......................................................................... v The Platinum Process.........................................................................................vi Report Organization..........................................................................................vii Bloomington’s Legacy ...................................................................................... viii QUALIFICATIONS: WHY PLATINUM? .................................................... 1−1 Why Platinum................................................................................................. 1-2 Quality of Life................................................................................................. 1-5 Health Promotion............................................................................................ 1-7 Environmental Harmony.................................................................................. 1-9 Economic Resiliency...................................................................................... 1-12 INDIVIDUAL TIME TRIALS: FIVE PRIORITIES.......................................... 2−1 The Five Es & Bloomington’s -

January 2012 at BFI Southbank

PRESS RELEASE November 2011 11/77 January 2012 at BFI Southbank Dickens on Screen, Woody Allen & the first London Comedy Film Festival Major Seasons: x Dickens on Screen Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is undoubtedly the greatest-ever English novelist, and as a key contribution to the worldwide celebrations of his 200th birthday – co-ordinated by Film London and The Charles Dickens Museum in partnership with the BFI – BFI Southbank will launch this comprehensive three-month survey of his works adapted for film and television x Wise Cracks: The Comedies of Woody Allen Woody Allen has also made his fair share of serious films, but since this month sees BFI Southbank celebrate the highlights of his peerless career as a writer-director of comedy films; with the inclusion of both Zelig (1983) and the Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) on Extended Run 30 December - 19 January x Extended Run: L’Atalante (Dir, Jean Vigo, 1934) 20 January – 29 February Funny, heart-rending, erotic, suspenseful, exhilaratingly inventive... Jean Vigo’s only full- length feature satisfies on so many levels, it’s no surprise it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made Featured Events Highlights from our events calendar include: x LoCo presents: The London Comedy Film Festival 26 – 29 January LoCo joins forces with BFI Southbank to present the first London Comedy Film Festival, with features previews, classics, masterclasses and special guests in celebration of the genre x Plus previews of some of the best titles from the BFI London Film Festival: -

Final Research Report

Comparing Long-Term Outcomes of Two Collaborative Care Approaches for People with Depression Kenneth Wells, MD1,2,3,4,5 ; Loretta Jones, MA6,7, ; Michael Ong, MD2 ; Wayne Aoki, PhD8 ;Thomas Belin, PhD3 ; Elizabeth Bromley, MD1,2,5 ; Bowen Chung, MD 1,2,4,9 ; Elizabeth Dixon, PhD MSN/MPH, RN 10 ; Megan Dwight Johnson, MD 11 ; Felica Jones 6 ; Paul Koegel, PhD 4 ;Dmitry Khodyakov, PhD4 ; Craig Landry, PhD1,2 ; Elizabeth Lizaola, MPH 1,2 ; Norma Mtume, MHS, MA, MFT 12 ; Victoria Ngo, PhD4 ; Judith Perlman, MS4 ; Esmeralda Pulido, MPH13 ; Vivian Sauer, MSW14; Cathy Sherbourne, PhD 4 ; Aziza Lucas Wright 4,6,15;Lingqi Tang, PhD1,2; Yolanda Whittington, MSW 9 ; Pluscedia Williams 6,7 ;Lily Zhang, MS1,2 ; Marvin Southard, DSW18 ;Jeanne Miranda, PhD 1,2 ; Sheryl Kataoka, MD, MSHS 1,2 ; Roya Ijadi-Maghsoodi, MD, MSHPM 2,5 ; Chantal Figueroa, PhD 15; Enrico Castillo, MD, MSHPM 9,16; Heather Patel, MPH 16 ;Mienah Zulfacar Sharif 16; S. Megan Helle 16 ;Krystal Griffith, MPH 1,2; Farbod Kadkhoda, MA 1,2; Priscilla Shorter 17; Rosalinda Cardenas 1,2;Joseph Mango, MFA 1,2 ; Erika Orellana 1,2 1David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles 2Semel Institute, University of California, Los Angeles 3Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 4RAND Health Program/ The RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA 5Greater Los Angeles Veterans Administration Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA 6Healthy African American Families Phase II, Los Angeles, CA 7Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, -

Bugsy Siegel Part 30 of 32

FEDERAL OF STiGA'iION BQQQK 5'/£6EL PART #i%// W0/C // 7 PAGES AVAILABLETHIS PART???lg 17/ _ FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION FILES CONTAINED IN THIS PART A FILE # /0 -0 .-. 92 _ b_§"_.Q L,_.' '/.J ég: 3/$/3 ..§§*c 4}-Z_§/Z_L92fo_/./_2___PAGES AVAILABLE I & .. A 2 LL __-ll,1_,92!Z vo/.1! T ief _. 7 ya _ _ .. éz-1*'1._!..2....__.__._ v@/-2! ¢z-as/2 v<>/.~/!35 _-.""'.....-2;.-::.'.: :.=- .-"'='-"-s -*=.=-*=i~>*'*'"@~'.'------~.--*--~*-'- -- -* .1. ' w- 0 _ - __ . I; 1 ._ 0 _ A_ A-~-{in . V _ VP 3 0 ' . 0- . .;§ - -~ £11.: osscnwon . »i-_: I? Q . .- D . ;;;.~ ¢-§- . aumzau me % -'-- £ ' --. ._.4 _ I-r-"P - -. I Q -1» Q jO &$.U_BJECT /6?/és?i§§¢'@¢=4 Y .0 FILE N0.__; /~'>-*/$>.%__... ' /7 L sscfnowmo. 92--.5 _ . I 1- . -. O 0 _ . ' _ ;'1 _ . 8 ; SE'RlALS.____.i_________..% ' '9 /u - '4 --iv-< 1I - "E I -0 . - 1°} Y __- -bi.-¥ . -i "." _ " " '-:_'u--4 = Q 1 ll 1-._ ..-_- .. - .- I '5 _ _ - ' - r0 - -- 3 ___ _ . ' . ...-. .-. ' ; -_.~.., -. _ ... ,...- ...,_~.. ., .-4._,, .,..._,.¢a-__.. ... _-.-...-¢....._,_.....u._-.....@ _ ..v__ ... V_.m. 92 ..._..... mg; >?i492llAlIl*y-Q9292 .... ..= .... , 4. ,.,, , in hon ttoaglt gag .<. in Into 6 Int, j 811109 ' cuc M00010 £3101-00904 la an D 1 IO_I"II0L'.~_'-,0 0 QM liliiiiingj gs-_' IPPMI if III Icfhr 5,-_ QCPIII flat III 9* - should In I11"! ' |-- .[-,,¢ V. -

Driving Miss Daisy – Mother &

Driving Miss Daisy 1 In the dark we hear a car ignition turn on, and then a horrible crash. Bangs and booms and wood splintering. When the noise is very loud, it stops suddenly and the lights come up on Daisy Werthan’s living room, or a portion thereof. Daisy, age 72, is wearing a summer dress and high heeled shoes. Her hair, her clothes, her walk, everything about her suggests bristle and feist and high energy. She appears to be in excellent health. Her son, Boolie Werthan 40, is a businessman, Junior Chamber of Commerce style. He has a strong capable air. The Werthans are Jewish, but they have strong Atlanta accents. DAISY. No! BOOLIE. Mama! DAISY. No! BOOLE. Mama! DAISY. I said no, Boolie, and that’s the end of it. BOOLIE. It’s a miracle you’re not laying in Emory Hospital---- or decked out at the funeral home. Look at you! You didn’t even break your glasses. DAISY. It was the car’s fault. BOOLIE. Mama, the car didn’t just back over the driveway and land on the Pollard’s garage all by itself. You had it in the wrong gear. DAISY. I did not! BOOLIE. You put it in reverse instead of drive. The police report shows that. DAISY. You should have let me keep my La Salle. BOOLIE. Your La Salle was eight years old. DAISY. I don’t care. It never would have behaved this way. And you know it. BOOLIE. Mama, cars, don’t behave. They are behaved upon. The fact is you, all by yourself, demolished that Packard. -

Movie Store Collections- Includes Factory Download Service

Kaleidescape Movie Store Collections- Includes Factory Download Service. *Content Availability Subject to Change. Collection of 4K Ultra HD & 4K HDR Films Academy Award Winners- Best Picture Collection of Family Films Collection of Concerts Collection of Best Content from BBC Our Price $1,250* Our Price $1,450* Our Price $2,450* Our Price $625* Our Price $650* MSCOLL-UHD MSCOLL-BPW MSCOLL-FAM MSCOLL-CON MSCOLL-BBC 2001: A Space Odyssey 12 Years a Slave Abominable Adele: Live at the Royal Albert Hall Blue Planet II A Star Is Born A Beautiful Mind Aladdin Alicia Keys: VH1 Storytellers Doctor Who (Season 8) Alien A Man for All Seasons Alice in Wonderland Billy Joel: Live at Shea Stadium Doctor Who (Season 9) Apocalypse Now: Final Cut All About Eve April and the Extraordinary World Celine Dion: Taking Chances World Tour - The Concert Doctor Who (Season 10) Avengers: Endgame All Quiet on the Western Front Babe Eagles: Farewell 1 Tour — Live from Melbourne Doctor Who (Season 11) Avengers: Infinity War All the King's Men Back to the Future Elton John: The Million Dollar Piano Doctor Who Special 2012: The Snowmen Baby Driver Amadeus Back to the Future Part II Eric Clapton: Slowhand at 70 - Live at the Royal Albert Hall Doctor Who Special 2013: The Day of the Doctor Blade Runner 2049 American Beauty Back to the Future Part III Genesis: Three Sides Live Doctor Who Special 2013: The Time of the Doctor Blade Runner: The Final Cut An American in Paris Beauty and the Beast Hans Zimmer: Live in Prague Doctor Who Special 2014: Last Christmas Blue Planet II Annie Hall Cars INXS: Live Baby Live Doctor Who Special 2015: The Husbands of River Song Bohemian Rhapsody Argo Cars 2 Jackie Evancho: Dream with Me in Concert Doctor Who Special 2016: The Return of Doctor Mysterio Chinatown Around the World in 80 Days Cars 3 Jeff Beck: Performing This Week..