Emblems of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eureka Flag

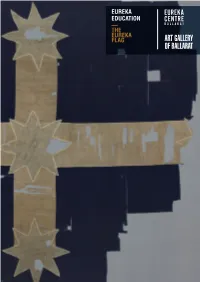

EUREKA EDUCATION — THE EUREKA FLAG 29 THE EUREKA FLAG image, right & p. 29 unknown artist The flag of the Southern Cross (Eureka Flag) 1854 wool, cotton Actual size: 260.0 x 324.0cm (irreg.) Original size: 260.0 x 370.5 cm Gift of the King family, 2001 Collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat The original Flag of the Southern Cross (The Eureka Flag) can be viewed at the Eureka Centre, on loan from the Art Gallery of Ballarat. It was made in 1854. ORIGINS OF THE FLAG It is not known who designed or made the flag. It is widely believed that it was designed by a Canadian miner, Henry Charles Ross (see Key figures) There are traditional stories which suggest that it may have been sewn by three women – Anne Withers, Anne Duke and Anastasia Hayes (see Women on the goldfields) but there are alternative claims that the claim was made by local tentmakers Edwards and Davis. Neither of these stories have been proven. The flag was first raised at a Ballarat Reform League meeting at Bakery Hill on 29 November 1854. It was then moved to the Eureka Stockade where it was flown until torn down after the battle on 3 December, only five days later. FLAG DESCRIPTION The flag is 2.6 metres high and 4metres wide – more than double the size of a standard flag. The blue fabric is mostly cotton, while wool has been used for the white cross and the stars. The flag is made up of multiple panels of fabric that have been ART stitched together. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Proc. XVII International Congress of Vexillology 149 Copyright ©1999, Southern African Vexillological Assn. Australia’s new flag Peter Martinez (ed.) nullius - land belonging to none - is now discredited.^ Australia’s present makes sense only from its past. The seeds of its future and,its future flag are already there. Integration of symbols requires the integrity of candour. The elemental idea of this paper is that integration of peoples and syrnbols comes from integrity of mind. Integrity will not ignore atrocities. Nor Australia’s new flag - will it cultivate political correctness of one kind or another. Civic harmony grows from mutual respect for different traditions and from shared experience. a pageant of colours and What many in Australia still recognise as mateship. The second point of reference in this paper is the symbolic power of colour. integrated symbols Colour crosses many margins and several meanings. Applied to people who stand behind flags and symbols, colour is an atavistic and sensitive issue in any couptry. Colour, and the differences of which the rainbow is an ancient symbol,^ A.C. Burton is a subtle issue for Australia, which seeks a harmony of cultures. Despite the goodwill and the good works of the last 200 years that out- measure mcdice, Australia is still a whole continent where a nation-state - but ABSTRACT: The history and significance of colour themes in Aus not quite a state of nation - has been built upon the dispossession of peo tralian vexillography are explored to provide a reference pdint for ples. Sovereign in custom, language, ritual, religion, in seals and symbols, and evolving and depicting old symbols in a new way, to weave from an above all in deep relationship to the land, Australia’s Aboriginal people are still ancient Dreaming new myths for a nation’s healing. -

An Argument from Design

Raising the Standard: An Argument from Design Tony Burton Abstract The creative process and principles informing the design of some special purpose and other flags lead to conclusions for flag design in general. The dynamics of metaphor and shape- shifting are considered. The scope for greater pageantry and innovation in flag design is explored. Current national flags of complex or awkward design present a challenge. Possible remedies are suggested. To paraphrase a famous utterance, the known delivers the unknown, and as at least one national flag of recent vintage demonstrates, the unknown can lead to an unforeseen, but serendipitous result. Among the many instances of how not to design a flag, how to is more worthwhile. Vexillologists have higher standards. Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 83 RAISING THE STANDARD: AN ARGUMENT FROM DESIGN Tony Burton Flags Australia Tony Burton—Raising the Standard 84 Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology—2011 RAISING THE STANDARD: AN ARGUMENT FROM DESIGN INTRODUCTION FLAG DESIGN REALITIES GUIDELINES SOME CONGRESS FLAGS ICV 24 ICV 26 SHAPE-SHIFTING ICV 8 OTHER FLAGS CANADA BANGLADESH SURINAM(E) SOUTH AFRICA DESIGN CHANGE POSSIBILITIES MOZAMBIQUE CYPRUS DOMINICA ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES DESIGN ECONOMY AND A FUTURE FLAG AUSTRALIA EUREKA A CONSERVATIVE APPROACH RADICAL ORIGAMI A PARAGON OF DESIGN PRACTICAL GUIDELINES THE EUREKA MOMENT —A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK NOTES BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDIX A BANNER OF THE 26TH ICV SYDNEY 2015 APPENDIX B CANADA’S FLAG DESIGN QUEST Tony Burton—Raising the Standard 85 Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology—2011 RAISING THE STANDARD: AN ARGUMENT FROM DESIGN INTRODUCTION Flags have evolved in many ways from the medieval models paraphrased in the title slide— and not always with their clarity and flair. -

Objection Received to the Australia First Party Logo Application

26 April 2016 The Manager Australian Electoral Commission National Office Locked Bag 4007 CANBERRA ACT 2601 Via email [email protected] and facsimile 02 6215 9999 Dear Sir or Madam, Opposition to the registration of the proposed logo for the ‘Australia First’ party. The Australian Worker’s Union is Australia’s largest blue-collar union with a history dating back until 1896. Our union has been central to the industrial history of Australia and, on this basis, the AWU feels qualified to oppose the logo registration proposed by the so-called ‘Australia First’ party. While not wishing to provide the Australian Electoral Commission with a history lesson of which it is no doubt aware, it is vital to understand the cultural underpinnings of the Eureka Flag. Put simply, the Eureka Flag is central to Australia’s history and its working class values. It has a legendary status and understood meaning in the community. The Eureka Flag is central to the iconic Eureka Stockade dispute of 1854, an event that many unions jointly lay claim to in their historic and cultural underpinnings. The original flag still exists in the Ballarat Fine Art Museum where it stands as an icon to working Australians. The AWU encourages the AEC to closely consider and investigate the rich history of the symbol. Such national cultural icons are not for political hijacking. They should not be the plaything of those who seek to benefit from their appropriation. The AWU notes that the Electoral Commission can refuse to register a logo of a political party if the logo “is obscene; or so nearly resembles the logo of any other person that it is likely to be confused with or mistaken for that logo.” For the ‘Australia First’ party to attempt to hijack the Eureka Flag offensive to all trade unionists past and present. -

Info-FIAV 37

Info-FIAV No. 37, July 2015 ISSN 1560-9979 Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques Federación Internacional de Asociaciones Vexilológicas International Federation of Vexillological Associations Internationale Föderation Vexillologischer Gesellschaften www.fiav.org TWENTY-FOURTH SESSION OF THE FIAV GENERAL ASSEMBLY SEPTEMBER 1, 2015 Every FIAV Member is strongly encouraged to appoint a delegate and alternate to represent it at the Twenty-Fourth Session of the FIAV General Assembly on September 1, 2015. If no person from a FIAV Member is able to come to the General Assembly Session, that FIAV Member is strongly encouraged to appoint as its delegate either the delegate of another FIAV Member or one of the three FIAV Officers. This will be the third General Assembly session to which current article 8 of the FIAV Constitution applies. Credentials should be brought to the General Assembly Session. If at all possible, credentials should be on the Member’s official stationery. The suggested form of written credentials is as follows: To the President of the Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques: [Name of FIAV Member association or institution] appoints [name of person (and alternate, if desired)], as its delegate to the Twenty-Fourth Session of the FIAV General Assembly, to be convened September 1, 2015, in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. [Delegate’s name] has full powers to act on behalf of [name of FIAV Member association or institution] during the Twenty-Fourth Session of the General Assembly [or] The powers of [delegate’s name] to act on behalf of [name of FIAV Member association or institution] during the Twenty-Fourth Session of the General Assembly are limited as follows: [describe]. -

Australian Working Songs and Poems - a Rebel Heritage

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2014 Australian working songs and poems - a rebel heritage Mark Gregory University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Gregory, Mark, Australian working songs and poems - a rebel heritage, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Humanities and Social Inquiry - History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2014. -

Eureka Centre and Eureka Stockade Memorial Park Interpretation Plan | 1

Introduction | Eureka Centre and Eureka Stockade Memorial Park Interpretation Plan | 1 EUREKA CENTRE AND EUREKA STOCKADE MEMORIAL PARK Interpretation Plan City of Ballarat 2020 2 Eureka Centre and Eureka Stockade Memorial Park Interpretation Plan | 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 Background 6 1. Introduction 10 1.1 Current interpretive offering 11 1.2 The story so far 12 2. Visitor trends and Audience development framework 14 2.1 Eureka Centre 16 2.2 Eureka Education program 17 2.3 Local visitory economy 18 2.4 Identifying audiences 19 2.5 Skimmers, dippers and divers 20 3. Community feedback 22 3.1 Consultation timeline 23 3.2 Consultation findings 26 4. Eureka themes and stories 28 5. Storytelling locations 34 5.1 Eureka Centre 35 5.2 Eureka Stockade Memorial Park 45 6. Interpretive approach 54 6.1 Community vision 56 6.2 Guiding principles 56 6.3 Learning objectives 56 6.4 Implementation plan 57 Cover image: ‘Swearing allegiance to the Southern Cross’ 1854, watercolour & ink on paper, Carles A. Doudiet, purchased by the Art Gallery of Ballarat with the assistance of many donors, 1996. Adjacent image: Ballarat East gold workings and miners cottages 1861, R. Daintree, State Library Victoria. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Ballarat’s First Peoples The City of Ballarat is proud to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Country that today includes Ballarat, the Wadawurrung and Dja Dja Wurrung peoples, and pays respect to all Elders, past, present and emerging, as well as Elders from other communities who reside here today. They hold the memories, traditions, culture and hope of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people around Australia. -

To View the Full Eureka Education

EUREKA EDUCATION KIT EUREKA EDUCATION KIT — The Art Gallery of Ballarat and Eureka Centre acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which the Gallery and Eureka Center stand, the Wadawurrung people of the Kulin nation, and recognise their continuing connection to the land and waterways. We pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging and extend this to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People. On the cover: Charles A Doudiet Eureka riot 17th October (1854) 1854 (detail) watercolour on paper, 16.8 x 23.7 cm Purchased by the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery with the assistance of many donors, 1996 Principal Donors: Victorian Government through the Community Support Fund, Pam Davies, Eureka Stockade Memorial Committee of Management, Blair Ritchie, Rotary Club of Ballarat South, Wendouree Charitable Fund; Major Donors: Commercial Union Assurance Co., Janet Cowles, Bob & Emma House, Rex Irwin Art Dealer, Mabs Taylor, Peter Tobin, Voi & John Williams: plus 80 donors from the community. Collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat The Art Gallery of Ballarat and the Eureka Centre acknowledges the support of the Department of Education Training, Victoria, through the Strategic Partnerships Program. ABOUT An overview of the background, themes and key protagonists in the Eureka Stockade. With activities and supplementary resources. OVERVIEW This kit has been jointly produced by the Art Gallery of Ballarat and the Eureka Centre Ballarat to support teachers/educators in teaching content relating to the Eureka Stockade and the Victorian goldfields, as specified in the Australian Curriculum. Each chapter of the guide is focused on a broad theme and is followed by a series of suggested activities and discussion topics to be used alone, or as a starting point for unit planning. -

2030: a Vision for the Eureka Centre

2030: A VISION FOR THE EUREKA CENTRE The City of Ballarat 2019 1 CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Background 4 Strategic Context 5 Approach 6 Purpose 7 Imagining The Future 8 Vision Statement 9 Mission 10 Strategic Recommendations 11 Appendix 1 14 Appendix 2 15 Appendix 3 16 Adjacent image: ‘Eureka Riot 17th October’ 1854, original artwork, C. Doudiet, Art Gallery of Ballarat. 2 | 2030: A Vision for the Eureka Centre 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Eureka story is at once a profound and compelling Australian and global story. It is a touchpoint in Australia’s history, designated as a place in time where the foundations of Australian democracy were laid. Eureka is seen as the embodiment of hope and struggle in the face of adversity and has become a beacon for equality, unity and the right to a fair go, which now lies at the heart of the Australian spirit and identity. Its broad appeal to different sets of values, aspirations and ideals has ensured it continues to endure and resonate even after several generations. Eureka’s deep resonance in the Australian imagination underpins ‘2030: A Vision for the Eureka Centre’. The 2030 Vision imagines a successful and financially sustainable future for the Eureka Centre as a leading national cultural institution and much-loved visitor attraction. This vision is committed to democratizing the Eureka Centre and building its reputation through a commitment to innovative and accessible programming, social space activation and the integration of the visitor experience into community life. It presents strategic advice from the Eureka Centre Community Advisory Committee, which was established by the City of Ballarat to support the transition from the Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka (M.A.D.E). -

VISITOR GUIDE EUREKA CENTRE BALLARAT Welcome to the Eureka Centre Ballarat

VISITOR GUIDE EUREKA CENTRE BALLARAT Welcome to the Eureka Centre Ballarat Each year we welcome people from around the world who seek a meaningful connection to one of Australia’s most significant foundation stories – the Eureka Rebellion. The Eureka Centre respectfully At the Eureka Centre, we explore the social history and cultural acknowledges the Wadawurrung People impact of the Victorian goldrush and honour the stories of the men as the Traditional Owners of the land on which and women who risked their lives in the fight for miners’ rights. the Eureka Centre stands. We pay our respects The Eureka Centre is located at the Eureka Stockade Memorial to Elders past, present and emerging. We Park, considered to be the site of the 1854 Eureka Stockade where acknowledge their continuing connections the rebellion took place. It is home to one of the country’s most to Country and Culture. compelling historic artefacts – the Eureka Flag. The Eureka Stockade was a hastily erected wooden fort. It was just The Wadawurrung People are the Traditional as quickly dismantled following the attack by government forces on Owners of the land on which the Eureka 3 December 1854. Although, no tangible evidence of the structure Rebellion took place. While the Eureka Stockade remains, archaeological evidence was uncovered at the site between led to male suffrage in 1858 and informed the 1996 and 2012 that dates to the time of the Eureka Stockade. social reforms that followed, it was over 100 The Eureka Stockade Memorial Park is a place to contemplate the years until Australia’s First Nations People legacy and honour those involved in Eureka. -

Invitation from Miss World Australia

Website: www.australianflag.org.au August 2009 Inviittattiion From Miiss Worlld Austtralliia, Kattiie Riichardson: Please join us to celebrate the birthday of our Australian Flag of Stars and Crosses at 12 noon, Thursday 3rd September 2009 in Martin Place, Sydney NSW. "The Australian flag is our chief national symbol Mayor of by law, custom and tradition. When traveling to Leichhardt various countries, I often look up to the stars Jamie Parker at night, and when the Southern Cross is will be one visible, I think of Australia and our beautiful of the guest flag of 'Stars and Crosses' - which gives me a speakers at sense of pride and reminds me of my home Flag Day country. ”Katie Richardson - in Martin Place Miss World Australia 2008/09 Sydney City Trooper VC Mark Donaldson was awarded the Victoria Cross for outstanding bravery on 2 September 2008 in the Oruzgan Province Afganistan by deliberately drawing enemy fire from the wounded And carrying the Interpreter back to a vehicle. The ceremony was held at Government House Canberra on 16th January 2009 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES !To communicate positively to all Australians the importance and significance of our chief national symbol - the Australian National Flag. !To provide promotional and educational material concerning the Australian National Flag. !To promote the Australian identity overseas by the use of the Australian National Flag. !To support existing "fly the flag" programmes and encourage support from recognised service organisations. !To encourage personal identity with the Australian National This booklet on the birth of our flag is available from ANFA for Flag at all levels within the community. -

126Th ANNIVERSARY of the BATTLE of the EUREKA STOCKADE Papers Presented at the 6Th Annual Lalor Address on Community Relations

126th ANNIVERSARY OF THE BATTLE OF THE EUREKA STOCKADE Papers presented at the 6th Annual Lalor Address on Community Relations held at The Playhouse, Canberra Theatre Centre, Canberra on 3 December 1980 Commissioner for Community Relations Canberra I S S N 0 3 14 - 36 9 4 PROGRAM Pane Official Welcome The Hon. A.J. Grassby Australian Commissioner for Community Relations 1 The Australian Community and Anti-Heroes The Hon. Mr Justice M.D. Kirby Chairman of the Australian Law Reform Commission 4 Stereotypes The Rt. Rev. M.B. Challen Assistant Bishop Anglican Diocese of Perth 17 An Insight into the Relationship between Aboriginal and Other Australians Mr J. Hagan National Chairman National Aboriginal Conference 23 Belconnen High School Choir, Conducted by Miss Annette Pirani Advance Australia Fair Brother James' Air (23rd Psalm) The Rhythm of Life P.I., My Beautiful Home Pearly Shells Harmonie Choir, Conducted by Mr W. Hunt, MBE Kein Schbner Land Wiegenlied — Schubert Annchen von Tarau Heidenroslein Frohlicher Wanderer Bwcgomen Dance Team, St Michael's School, Palm Island Mr Eddie Robertson — Deputy Chairman of the Palm Island Community Council Mr Laurie Doughan — Teacher Dancers — Mr Carlo Allen Mr Algon Congoo Thomas Clumpoint Bradley Foster Noel Coolwell Kelly Roberts Gary Prior Bindi Roberts Roy Prior Raymond Barry Noel Prior Patrick Barry lan Palmer Ashley Blanket Fletcher Daisy Lance Wotton Walter Barney Thomas Johnson OFFICIAL WELCOME BY THE HONOURABLE A.J. GRASSBY COMMISSIONER FOR COMMUNITY RELATIONS Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, Welcome to the sixth in the series of Annual Lalor Addresses on Com- munity Relations. The objective on this annual occasion, which marks the anniversary of the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, is to help build unity and amity among all sections of the Australian people.