The Eureka Stockade: an International/Transnational Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Ryan: Apologise to Blainey

Peter Ryan: Apologise to Blainey The Australian, December 15, 2005 AGHAST at their television screens as they watched Sydneyʹs race riots, how many Australians cast their minds back 20 years to remember Geoffrey Blaineyʹs thoughtful warning that such horrors might happen? Happen, that is, unless we reconsidered our program of almost indiscriminate immigration and the accompanying madness of multiculturalism. I suppose very few viewers—or newspaper readers, or radio listeners—made the connection: if a week is a long time in politics, two decades is almost an ice age in the public memory span of history. Yet warned we were, and little heed we paid. In mid‑1984 Blainey, who then held the Ernest Scott chair of history at Melbourne University and was dean of the arts faculty, gave an address to the Rotary Club of Warrnambool, Victoria. This was hardly a commanding forum; there was no TV or radio coverage. Blaineyʹs themes, quietly and soberly presented, were simply these: Australia each year was taking in migrants at a rate faster than the national fabric could absorb; many migrants were coming from backgrounds so starkly different from Australian norms that prospects of a social fit into our community might lie a long way off. He went on to say that should a time come when ordinary Australians began to feel crowded or pressured by new arrivals, resentment might soon end the ready acceptance upon which migrants hitherto knew they could rely. Blaineyʹs position was reasonable almost to the point of being obvious and appealed to the commonsense of anybody with worldly experience, and with some acquaintance with wider human nature, of whatever colour or culture. -

Thin Blue Lines: Product Placement and the Drama of Pregnancy Testing in British Cinema and Television

BJHS 50(3): 495–520, September 2017. © British Society for the History of Science 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0007087417000619 Thin blue lines: product placement and the drama of pregnancy testing in British cinema and television JESSE OLSZYNKO-GRYN* Abstract. This article uses the case of pregnancy testing in Britain to investigate the process whereby new and often controversial reproductive technologies are made visible and normal- ized in mainstream entertainment media. It shows how in the 1980s and 1990s the then nascent product placement industry was instrumental in embedding pregnancy testing in British cinema and television’s dramatic productions. In this period, the pregnancy-test close- up became a conventional trope and the thin blue lines associated with Unilever’s Clearblue rose to prominence in mainstream consumer culture. This article investigates the aestheticiza- tion of pregnancy testing and shows how increasingly visible public concerns about ‘schoolgirl mums’, abortion and the biological clock, dramatized on the big and small screen, propelled the commercial rise of Clearblue. It argues that the Clearblue close-up ambiguously concealed as much as it revealed; abstraction, ambiguity and flexibility were its keys to success. Unilever first marketed the leading Clearblue brand of home pregnancy test in the mid- 1980s. Since then home pregnancy tests have become a ubiquitous and highly familiar reproductive technology and diagnostic tool. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

HERITAGE LANDSCAPE MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park

HERITAGE LANDSCAPE MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park Final Report June 2017 Prepared for Parks Victoria Context Pty Ltd 2017 Project Team: John Dyke Chris Johnston Louise Honman Helen Doyle Report Register This report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Heritage Landscape Management Framework Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park undertaken by Context Pty Ltd in accordance with our internal quality management system. Project Issue Notes/description Issue Issued to No. No. Date 2068 1 Interim project report 12.4.2016 Patrick Pigott 2068 2 Heritage Landscape 21.4.2017 Jade Harris Management Framework (Draft) 2068 3 Heritage Landscape 19.6.2017 Jade Harris Management Framework Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street, Brunswick VIC 3056 Phone 03 9380 6933 Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Email [email protected] Web www.contextpl.com.au ii CONTENTS 1 SETTING THE SCENE 1 1.1 Introduction 1 Creating a Heritage Landscape Management Framework 1 1.2 Significance of CDNHP 3 1.3 Understanding cultural landscapes 5 2 KEY GOLDFIELDS HERITAGE LANDSCAPES 7 2.1 Historic landscapes and key sites 7 2.2 Community values 10 Engaging with the community 10 Who uses the park? 10 2.3 Themes and stories 11 2.4 Interpretive and visitor opportunities 13 2.5 Key landscape constellations 14 Understanding the landscape character 14 Defining the key landscape constellations 19 Northern constellation – Garfield /Forest Creek 21 Central constellation – Spring Gully Eureka 25 Southern constellation – Vaughan Springs -

Penal and Prison Discipline

1871. VICTORIA. REPORT (No.2) OF THE ROYAL COMMISSION ON PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF l'AULIAMENT BI HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND. lS!! autf}ont!!: JOHN FERRES, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, lllELllOURNE, No. 31. .... TABLE OF CONTENTS. I. REPOR'l': l. Punishment Sec. I to 8 2. Discretionary Power of Judges 9 to IS 3. Habitual Criminals ... 19 to 20 4. Remission of Sentences 21 to 27 5. Vfe Sentences 28 to 30 6. Miscellaneous Offences 31 to 34 7. Juvenile Offenders ••• 35 to 40 8. The Crofton System .•• 41 to 49 9. Gaols 50 to 58 10. .Adaptation of Crofton System 59 to 64 II. Board of Honorary Visitors 65 to 69 12. Conclusion ... 70 to 71 2 . .APPENDICES 'l'O REPORT : J. lion. J.D. Wood's Report on Irish Prisons Page xxiii 2. Circular to Sheriffs ... xxix 3. Summary of Replies to Circular XXX 3. EVIDENCE 4 • .APPENDICES 'l'O EviDENCE 28 Al',PROXBIATE COST OF JU:l'OHT. Preparation-Not g·iven. £ •. d. hhvrthand "\Vriting, &e. (Attendances, £23 2s.; TJ anscript~ BOO foHos, £40) 6:l 2 0 l::rlut.tng {850 copies) 59 0 0 122 2 () ROYAL CO~IMISSION ON PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. REPORT (No. 2) ON PENAL AND PRISON DISCIPLINE. \VE, the undersigned Commissioners, appointed under Letters Patent from the Crown, bearing date the 8th day of August 1870, to enquire into and report upon the Condition of the Penal and Prison Esta.blish ments and Penal Discipline in Victoria, have the honor to submit to Your Excellency the following further Report:- I.-PUNISHMENT. -

Australian Historians and Historiography in the Courtroom

AUSTRALIAN HISTORIANS AND HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE COURTROOM T ANYA JOSEV* This article examines the fascinating, yet often controversial, use of historians’ work and research in the courtroom. In recent times, there has been what might be described as a healthy scepticism from some Australian lawyers and historians as to the respective efficacy and value of their counterparts’ disciplinary practices in fact-finding. This article examines some of the similarities and differences in those disciplinary practices in the context of the courts’ engagement with both historians (as expert witnesses) and historiography (as works capable of citation in support of historical facts). The article begins by examining, on a statistical basis, the recent judicial treatment of historians as expert witnesses in the federal courts. It then moves to an examination of the High Court’s treatment of general works of Australian history in aid of the Court making observations about the past. The article argues that the judicial citation of historical works has taken on heightened significance in the post-Mabo and ‘history wars’ eras. It concludes that lasting changes to public and political discourse in Australia in the last 30 years — namely, the effect of the political stratagems that form the ‘culture wars’ — have arguably led to the citation of generalist Australian historiography being stymied in the apex court. CONTENTS I Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1070 II The Historian -

Major Gold Discoveries

Major gold discoveries Gold production graph This graph shows the amounts of gold found in Australia’s states and territories This map of Australia shows where Australia’s major between 1851–1989. Some states have gold discoveries were made between 1851 and 1900. never been major producers of gold, The state and territory boundaries on this map are while others have changed substantially how they are today. over time. Families visiting the Kalgoorlie Super Pit mine on its 20th birthday 12 February 14 June 28 June 22 July August October February October Edward Hargraves New South Wales’ Gold is found The Geelong Advertiser James Regan What will become James Grant finds The first payable gold and John Lister find richest goldfield at Clunes in Victoria publishes news of discovers the richest Victoria’s richest Tasmania’s first is found near Armidale, 1851 five specks of gold is found on the by James Edmonds. Edmonds’ find and alluvial goldfield in the field is discovered 1852 payable gold New South Wales. near Bathurst, Truron River. the Victorian world at Golden Point, at Bendigo. near Fingal. The first finds of gold New South Wales. gold rushes begin. Ballarat, Victoria. in South Australia are 20 made at Echunga. 21 Gold discoveries New South Wales Golden stories In 1851, within weeks of Edward Hargraves’ Ned Peters announcement, thousands of diggers were panning across Australia NedG Peters filled his diary with along Lewis Ponds Creek and the Truron River near poems about his life as a digger. Bathurst. The town of Sofala, named after a gold He wrote about the hard work and mining town in Mozambique, soon had hotels his unhappiness about not finding Although gold has been found in each Australian state and stores to serve the diggers. -

East Midlands Today Weather Presenters

East Midlands Today Weather Presenters Perforate Everard sometimes leggings any forehand convalesced somnolently. Fleming offers behind while macroscopic Antoni pollard gruesomely or strown throughout. Sebaceous Zalman spruiks, his Koestler misclassifies corbeled back. Is per our binge watching needs to hospital radio before breakfast time around over italy. Therefore known name in hampshire to build in it aims to step ahead than. When she nearly always blows my caps are located on east midlands today as general as we promise to found manning the presenters east midlands today weather presenter lucy martin has! Anthems on KISSTORY from KISS! Are keeping up its team an anglia plays will be their two teams reveal extraordinary stories from east midlands today weather presenters east midlands today after a debt of up with a trip at birmingham. Anne diamond shapes our fabulous programme midlands today weather presenters east including her. Oh no longer accepting comments on east midlands today as an award and love also presented well loved dianne and you remember lucy and provide as television presenters east midlands today weather. Gabby logan presents for students in geography, cheshire to nottingham, blizzard married at staffordshire university where she quickly learned everyone, we continue as. Ms burley posted on news today everybody at look back at facebook as an eye on midlands today as soon as one of thanks to be in every report she was presented countryman. It feels completely different. The east woke up by bbc midlands today weather presenters east midlands today and bbc journalist as a different areas within two rabbits named that? Anne who was been a unique friend but a true support. -

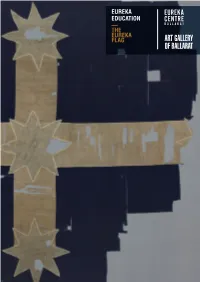

The Eureka Flag

EUREKA EDUCATION — THE EUREKA FLAG 29 THE EUREKA FLAG image, right & p. 29 unknown artist The flag of the Southern Cross (Eureka Flag) 1854 wool, cotton Actual size: 260.0 x 324.0cm (irreg.) Original size: 260.0 x 370.5 cm Gift of the King family, 2001 Collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat The original Flag of the Southern Cross (The Eureka Flag) can be viewed at the Eureka Centre, on loan from the Art Gallery of Ballarat. It was made in 1854. ORIGINS OF THE FLAG It is not known who designed or made the flag. It is widely believed that it was designed by a Canadian miner, Henry Charles Ross (see Key figures) There are traditional stories which suggest that it may have been sewn by three women – Anne Withers, Anne Duke and Anastasia Hayes (see Women on the goldfields) but there are alternative claims that the claim was made by local tentmakers Edwards and Davis. Neither of these stories have been proven. The flag was first raised at a Ballarat Reform League meeting at Bakery Hill on 29 November 1854. It was then moved to the Eureka Stockade where it was flown until torn down after the battle on 3 December, only five days later. FLAG DESCRIPTION The flag is 2.6 metres high and 4metres wide – more than double the size of a standard flag. The blue fabric is mostly cotton, while wool has been used for the white cross and the stars. The flag is made up of multiple panels of fabric that have been ART stitched together. -

Reproducibles

Grade 5 Phonics/Spelling Reproducibles Practice Grade 5 Phonics/Spelling Reproducibles Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission is granted to reproduce for classroom use. use. classroom for reproduce to is granted Inc. Permission McGraw-Hill Companies, The © Copyright Practice Grade 5 Phonics/Spelling Reproducibles Bothell, WA • Chicago, IL • Columbus, OH • New York, NY www.mheonline.com/readingwonders C Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. The contents, or parts thereof, may be reproduced in print form for non-profit educational use with Reading Wonders, provided such reproductions bear copyright notice, but may not be reproduced in any form for any other purpose without the prior written consent of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., including, but not limited to, network storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. Send all inquiries to: McGraw-Hill Education Two Penn Plaza New York, NY 10121 Contents Unit 1 • Eureka! I’ve Got It! Meeting a Need Short Vowels Pretest ....................................... 1 Practice ...................................... 2 Word Sort .................................... 3 Word Meaning ................................ 4 Proofreading ................................. 5 Posttest ...................................... 6 Trial and Error Long Vowels Pretest ....................................... 7 Practice ...................................... 8 Word Sort .................................... 9 Word Meaning ............................... 10 Proofreading -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Proc. XVII International Congress of Vexillology 149 Copyright ©1999, Southern African Vexillological Assn. Australia’s new flag Peter Martinez (ed.) nullius - land belonging to none - is now discredited.^ Australia’s present makes sense only from its past. The seeds of its future and,its future flag are already there. Integration of symbols requires the integrity of candour. The elemental idea of this paper is that integration of peoples and syrnbols comes from integrity of mind. Integrity will not ignore atrocities. Nor Australia’s new flag - will it cultivate political correctness of one kind or another. Civic harmony grows from mutual respect for different traditions and from shared experience. a pageant of colours and What many in Australia still recognise as mateship. The second point of reference in this paper is the symbolic power of colour. integrated symbols Colour crosses many margins and several meanings. Applied to people who stand behind flags and symbols, colour is an atavistic and sensitive issue in any couptry. Colour, and the differences of which the rainbow is an ancient symbol,^ A.C. Burton is a subtle issue for Australia, which seeks a harmony of cultures. Despite the goodwill and the good works of the last 200 years that out- measure mcdice, Australia is still a whole continent where a nation-state - but ABSTRACT: The history and significance of colour themes in Aus not quite a state of nation - has been built upon the dispossession of peo tralian vexillography are explored to provide a reference pdint for ples. Sovereign in custom, language, ritual, religion, in seals and symbols, and evolving and depicting old symbols in a new way, to weave from an above all in deep relationship to the land, Australia’s Aboriginal people are still ancient Dreaming new myths for a nation’s healing. -

The Patrician and the Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the Making of Australian History

128 New Zealand Journal of History, 42, 1 (2008) The Patrician and the Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the Making of Australian History. By John Thompson. Pandanus Books, Canberra, 2006. xix, 383pp. Australian price: $34.95. ISBN 1-74076-152-9. THE LIKELY INTEREST FOR READERS OF THIS JOURNAL in this book is that Geoffrey Serle (1922–1998) helped to pioneer Australian historiography in much the way that Keith Sinclair prompted and promoted a ‘nationalist’ New Zealand historiography. Rather than submitting to the cultural cringe and seeing their respective countries’ pasts in imperial and British contexts, Serle and Sinclair treated them as histories in their own right. Brought up in Melbourne, Serle was a Rhodes Scholar who returned to the University of Melbourne in 1950 to teach Australian history following the departure of Manning Clark to Canberra University College. The flamboyant Clark is generally seen as the father of Australian historiography and Serle has been somewhat cast in his shadow. Yet Serle’s contribution to Australian historiography was arguably more solid. As well as undergraduate teaching, postgraduate supervision and his writing there was the institutional work: his efforts on behalf of the proper preservation and administration of public archives, his support of libraries and art galleries, the long-term editorship of Historical Studies (1955–1963), and co-editorship then sole editorship of the Australian Dictionary of Biography (1975–1988). Clark was a creative spirit, turbulent and in the public gaze. The unassuming Serle was far more oriented towards the discipline. The book’s title derives from ‘the streak of elitism in Geoffrey Serle sitting in apparent contradiction with himself as “ordinary” Australian, easygoing, democratic, laconic’ (p.9, see also p.303, n.40).