Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 71

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Locality Profiles Health and Wellbeing Children's Services Kettering

Locality Profiles Health and Wellbeing Children's Services Kettering 1 | Children’s JSNA 2015 Update Published January 2015, next update January 2016 INTRODUCTION This locality profile expands on the findings of the main document and aims to build a localised picture of those clusters of indicators which require focus from the Council and partner agencies. Wherever possible, data has been extracted at locality level and comparison with the rest of the county, the region and England has been carried out. MAIN FINDINGS The areas in which Kettering performs very similarly to the national average are detailed below. The district has no indicators in which it performs worse than the national average or the rest of the county: Life expectancy at birth for females (third lowest in the county) School exclusions Under 18 conceptions Smoking at the time of delivery Excess weight in Reception and Year 6 pupils Alcohol specific hospital stays in under 18s (second highest rate in the county) Admissions to A&E due to self-harm in under 18s (second highest in the county) 2 | Children’s JSNA 2015 Update Published January 2015, next update January 2016 KETTERING OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHY As a locality, a number of Kettering’s demographics conform with the Northamptonshire picture, particularly around household deprivation, occupational structure, qualifications and age. Kettering has a population of around 95,700, the second largest in the county, and the second highest number of households, although the average household size is second lowest in Northamptonshire. The area is predominantly White with a small BME population. Rather than spread evenly across a number of ethnic groups, over 50% fall within the Asian community. -

37 Brook Street Raunds Northamptonshire NN9

37 Brook Street Prominent trading location in Raunds town centre 592 sq ft ground floor retailing with double frontage Raunds Available to let on new lease Northamptonshire NN9 6LL Gross Internal Area approx. 8,323 sqft (773.2 sqm) Raunds occupies a strategic location adjacent to the A45 dual BUSINESS RATES carriageway within East Northamptonshire, which connects Rateable value £6,100 * directly with Junctions 15, 15A and 16 of the M1 motorway, some 15 miles to the west and to the A14 (Thrapston Junction * In line with current Government legislation, if 12) some 7 miles to the east. occupied by a business as their sole commercial property, they will pay no rates. The subject premises is situated within the heart of the town centre, with nearby occupiers including the Post Office, QD Applicants are advised to verify the rating assessment with Stores, Jesters Café and Mace Convenience Store. the Local Authority. ACCOMMODATION SERVICES The property comprises an open plan ground floor retail unit We are advised that mains services are connected to the benefitting from a suspended ceiling with inset lighting. premises). None have been tested by the agent. Ground Floor LEGAL COSTS Sales Area 55.06 sq m 592 sq ft Each party to bear their own legal costs. wc The first floor is subject to a residential conversion, although in VIEWING the early stages of marketing maybe available to let with the To view and for further details please contact: ground floor accommodation. Samantha Jones Email: [email protected] TENURE The ground floor retail unit is being offered to let on a new Mobile: 07990 547366 effective full repairing and insuring lease, for a term to be agreed. -

Framework Capacity Statement

Framework Capacity Statement Network Rail December 2016 Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement December 2016 1 Contents 1. Purpose 1.1 Purpose 4 2. National overview 2.1 Infrastructure covered by this statement 6 2.2 Framework agreements in Great Britain 7 2.3 Capacity allocation in Great Britain 9 2.4 National capacity overview – who operates where 10 2.5 National capacity overview – who operates when 16 3. Network Rail’s Routes 3.1 Anglia Route 19 3.2 London North East & East Midlands Route 20 3.3 London North Western Route 22 3.4 Scotland Route 24 3.5 South East Route 25 3.6 Wales Routes 27 3.7 Wessex Route 28 3.8 Western Route 29 4. Sub-route and cross-route data 4.1 Strategic Routes / Strategic Route Sections 31 4.2 Constant Traffic Sections 36 Annex: consultation on alternative approaches A.1 Questions of interpretation of the requirement 39 A.2 Potential solutions 40 A.3 Questions for stakeholders 40 Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement December 2016 2 1. Purpose Network Rail Framework Capacity Statement December 2016 3 1.1 Purpose the form in which data may be presented. The contracts containing the access rights are publicly available elsewhere, and links are provided in This statement is published alongside Network Rail’s Network Statement section 2.2. However, the way in which the rights are described when in order to meet the requirements of European Commission Implementing combined on the geography of the railway network, and over time, to meet Regulation (EU) 2016/545 of 7 April 2016 on procedures and criteria the requirements of the regulation, is open to some interpretation. -

Emergency Plan for Kettering, Corby and East Northamptonshire Councils

North Northamptonshire Safety and Resilience Partnership In association with Zurich Municipal Emergency Plan for Kettering, Corby and East Northamptonshire Councils Document Control Title Emergency Plan for Kettering, Corby and East Northamptonshire Councils Type of Document Procedure Related documents Annex A – Emergency Control Centre procedures Annex B – Emergency Contacts List Annex C – Incident & Decision Log Author Paul Howard Owner North Northamptonshire Safety & Resilience Partnership Protective marking Unprotected Intended audience All staff, partner agencies and general public Next Review Date: July 2014 History Version Date Details / summary of changes Action owner 1.0 1/7/13 Issued following a consultation period between Paul Howard February and June 2013 Consultees Internal: External Peer review by Safety & Resilience Team Peer review by emergency planning colleagues on County team Safety & Resilience Partnership Board Head of County Emergency Planning Team Corporate Management Teams in each Local Resilience Forum Coordinator authority Previous plan holders in Corby Borough Council Distribution List Internal: External No hard copies issued – available via each No hard copies issued – available through authorities’ intranet and electronic file link on external website of each authority system– see ‘footer’ on subsequent pages Available through Local Resilience Forum for file path of master document website Contents Section 1 Information 1.1 Requirement for plan 1 1.1.1 Definition of responders 1 1.1.2 Duties required by the -

Barby Parish Council Notice of Meeting

KILSBY PARISH COUNCIL NOTICE OF MEETING To members of the Council: You are hereby summoned to attend a meeting of Kilsby Parish Council to be held in Kilsby Village Hall, Rugby Road, Kilsby. Please inform your Clerk on 07581 490581 if you will not be able to attend. Members of the public and press are invited to attend a meeting of Kilsby Parish Council and to address the Council during its Public Participation session which will be allocated a maximum of 20 minutes. On……. TUESDAY 1st October, 2019 at 7.30pm In the Kilsby room of the Kilsby Village Hall, Rugby Road, Kilsby. 24th September, 2019. Please note that photographing, recording, broadcasting or transmitting the proceedings of a meeting by any means is permitted without the Council’s prior written consent so long as the meeting is not disrupted. (Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014). Please make yourself known to the Clerk. Parish Clerk: Mrs C E Valentine, 20 Styles Place, Yelvertoft, Northamptonshire,NN6 6LR ______Tel 07581 490581 e-mail [email protected]___________ 1 APOLOGIES 2 CO-OPTION to fill CASUAL VACANCIES 2.1 To note that there are two vacant seats on the Parish Council and to consider candidates who have expressed an interest in becoming a Councillor and co-opt a suitable candidate. 3 PUBLIC OPEN FORUM SESSION limited to 20 mins. 3.1 Public Open Forum Session Members of the public are invited to address the Council. The session will last for a maximum of 20 minutes with any individual contribution lasting a maximum of 3 minutes. -

Third Party Funding

THIRD PARTY FUNDING IS WORKING IAN BAXTER, Strategy Director at SLC Rail, cheers enterprising local authorities and other third parties making things happen on Britain’s complex railway n 20 January 1961, John F. Kennedy used being delivered as central government seeks be up to them to lead change, work out how his inaugural speech as US President more external investment in the railway. to deliver it and lever in external investment Oto encourage a change in the way of into the railway. It is no longer safe to assume thinking of the citizens he was to serve. ‘Ask DEVOLUTION that central government, Network Rail or not what your country can do for you,’ intoned So, the theme today is: ‘Ask not what the train operators will do this for them. JFK, ‘but what you can do for your country.’ the railway can do for you but what However, it hardly needs to be said, least of Such a radical suggestion neatly sums up you can do for the railway’. all to those newly empowered local railway the similar change of approach represented Central government will sponsor, develop, promoters themselves, enthusiastic or sceptical, collectively by the Department for Transport’s fund and deliver strategic railway projects that the railway is a complex entity. That March 2018 ‘Rail Network Enhancements required for UK plc, such as High Speed 2, applies not only in its geographical reach, Pipeline’ (RNEP) process, Network Rail’s ‘Open for electrification, long-distance rolling stock scale and infrastructure, but also in its regularly Business’ initiative and the ongoing progress of replacement or regeneration at major stations reviewed post-privatisation organisation, often devolution of railway planning and investment like London Bridge, Reading or Birmingham New competing or contradictory objectives, multiple to the Scottish and Welsh governments, Street. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Daventry and South Northamptonshire Conservative Associations

Daventry and South Northamptonshire 2013 Conservative Associations EVENTS You are welcome to attend all events Daventry Constituency Conservative Association Knightley branch invites you to: SEPTEMBER PIMMS PARTY 01/09/2013 ■ DCCA KISLINGBURY BRANCH- SUNDAY By kind invitation of Peter and Catherine Wakeford GARDEN PARTY ■ 12 noon until 3pm ■ 5 Mill Lane, Kislingbury, NN7 4BB ■ By kind invitation of Mr & Mrs Collins ■ Please contact Mr Leslie on 01604 830343. Badby Fields, Badby, NN11 3DD Sunday 4th August 12:00 noon 06/09/2013 ■ SNCA- INDIAN SUMMER DRINKS PARTY ■ 6:30PM ■ Wappenham Manor, Wappenham, Towcester, NN12 8SH ■ By kind invitation of Rupert and Georgie Tickets £12.50 Fordham ■ Tickets £15 ■ Drinks and Canapés ■ Please Please contact Catherine Wakeford on contact Janet Digby, by email on [email protected] or 01280 850332. 01327 876760 for tickets 18/09/2013 ■ SNCA- LUNCH N LEARN- ‘THE FUTURE South Northants Conservative Association OF FARMING’ ■ 11:00AM ■ The Priory, Syresham, NN13 Invite you to: 5HH ■ Guest Speaker Alice Townsend ■ By kind invitation of Clare & Malcolm Orr-Ewing ■ Please contact Janet Digby, by Indian Summer Drinks Party email on [email protected] or 01280 850332. By kind invitation of Rupert and Georgie Fordham OCTOBER Wappenham Manor, Wappenham, Towcester, NN12 8SH 03/10/2013■ DCCA KISLINGBURY BRANCH THEATRE Friday 6th September 2013 6:30PM TRIP TO SEE THE AWARD WINNING MUSICAL ‘CATS’ ■ 6:30pm at the theatre ■The Royal and Derngate Theatre, Northampton, NN1 1DP ■ Show plus wine and nibbles ■ £15 per ticket Drinks and Canapés £38 inclusive ■ Please contact Paul Southworth on 01604 832487 for further information. -

Spratton Parish Council Held on Tuesday 17Th June 2014 in the Village Hall, School Road, Spratton at 7.30 Pm

Chairman: Councillor Barry Frenchman Clerk: Mrs L Compton 12 Olde Forde Close Brixworth Northants NN6 9XF Tel/Fax 01604-880727 Email: sprattonpc@tiscali co.uk Minutes of a Meeting of Spratton Parish Council Held on Tuesday 17th June 2014 in the Village Hall, School Road, Spratton at 7.30 pm Present: Cllrs Barry Frenchman (Chairman), Tim Forster (Vice-Chairman), John Hunt, Fiona Keable, Rachel Baillie, Michael Heaton and Jay Tindale – 7 members In attendance: 3 members of the public 21.14 PUBLIC FORUM Members of the public and press are invited to address the Council at its Open Forum from 7.30 pm to 7.45 pm There were 3 members of the public in attendance who were awaiting the update on the Neighbourhood Plan. 22.14 RESOLUTION TO APPROVE APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Cllr Frenchman proposed acceptance of apologies from Cllr Blowfield, Cllr Ruaraidh-McDonald Walker and Cllr Pacey, seconded by Cllr Heaton and resolved to be approved by Parish Council. 23.14 RESOLUTION TO SIGN AND APPROVE MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL MEETING OF PARISH COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY 4TH JUNE 2014 (previously circulated) – Cllr Frenchman proposed approval of the minutes, seconded by Cllr Heaton and resolved to be approved by Parish Council. 24.14 MATTERS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MINUTES AND CLERK UPDATE REPORT (if any) – For Information only a) First Responders (209.13 b April Minutes) – to receive an update from Cllr Baillie – after some discussion and clarification that First Responders is part of the Ambulance Service and involves training people to be respond to 999 calls and not the same as the free HeartStart training which is a free 2 hour Emergency First Aid Course, Cllrs Baillie and Keable kindly agreed to look into both further and report back. -

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031

Pre-Submission Draft East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2/ 2011-2031 Regulation 19 consultation, February 2021 Contents Page Foreword 9 1.0 Introduction 11 2.0 Area Portrait 27 3.0 Vision and Outcomes 38 4.0 Spatial Development Strategy 46 EN1: Spatial development strategy EN2: Settlement boundary criteria – urban areas EN3: Settlement boundary criteria – freestanding villages EN4: Settlement boundary criteria – ribbon developments EN5: Development on the periphery of settlements and rural exceptions housing EN6: Replacement dwellings in the open countryside 5.0 Natural Capital – environment, Green Infrastructure, energy, 66 sport and recreation EN7: Green Infrastructure corridors EN8: The Greenway EN9: Designation of Local Green Space East Northamptonshire Council Page 1 of 225 East Northamptonshire Local Plan Part 2: Pre-Submission Draft (February 2021) EN10: Enhancement and provision of open space EN11: Enhancement and provision of sport and recreation facilities 6.0 Social Capital – design, culture, heritage, tourism, health 85 and wellbeing, community infrastructure EN12: Health and wellbeing EN13: Design of Buildings/ Extensions EN14: Designated Heritage Assets EN15: Non-Designated Heritage Assets EN16: Tourism, cultural developments and tourist accommodation EN17: Land south of Chelveston Road, Higham Ferrers 7.0 Economic Prosperity – employment, economy, town 105 centres/ retail EN18: Commercial space to support economic growth EN19: Protected Employment Areas EN20: Relocation and/ or expansion of existing businesses EN21: Town -

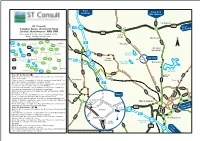

Southern Testing Location Map (Northampton)

From Leicester From A14 Mkt Harboro Harrington ST Consult A5199 A508 A14 M6 J19 J1 From Twigden Barns, Brixworth Road Kettering Creaton, Northampton NN6 8NN A5 A14 Tel: 01604 500020 - Fax: 01604 500021 Cold Email: [email protected] Ashby www.stconsult.co.uk A5199 Maidwell N A43 A508 A14 M6 Kettering Thrapston M1 J19 A14 Thornby A14 W e Rugby l A5199 fo Creaton rd Hanging J18 A43 A6 A45 R o a M45 A428 d Houghton J17 A508 Wellingborough J18 Hollowell A45 A428 Rushden M1 A428 Reservoir Daventry A45 See Inset Northampton A509 West A425 A6 M45 Haddon CreatonCreaton J16 Ravensthorpe A428 Brixworth J15a J17 Reservoir A5 J15 A43 A361 A428 Bedford A508 A361 Pitsford Towcester Ha M1 A509 rle Reservoir st on B5385 e R From M1 Northbound o Harborough a W d Road A43 Exit the M1 at junction 15a, Rothersthorpe Services and follow Long e l f signs to the A43. A5 Buckby o r Braunston d Once at the A43 roundabout, turn left and pass under the M1 to R Thorpeville o A508 arrive at a further roundabout, continue ahead. M1 a d Remain on the A43 over the next three roundabouts, at the next A45 roundabout take the third exit onto the A4500. Continue over the next two roundabouts and after a further 1/2 A5199 A5076 mile turn left onto the A428 Spencer Bridge Road. A428 Pass over the rail and river bridges and turn left onto the A5095 St Andrews Road. Inset At the junction with the A508 turn left onto Kingsthorpe Road. -

Easton Maudit Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan

EASTON MAUDIT CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL AND MANAGEMENT PLAN 1 ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT 1.1 The village of Easton Maudit is located about seven miles south of Wellingborough and eleven miles from Northampton. Most of the southern half of the parish of 730 hectares is on Boulder Clay at 90m – 110m AOD, but streams in the north draining towards Grendon Brook have cut deep-sided valleys through limestone, silts and clays [RCHME, Vol II, 1979]. The parish is two miles north to south and one mile east to west with the village itself located to the north. It is bounded on the east by Bozeat, north by Grendon and west by Yardley Hastings, lying on the borders of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire and west of the road between Wellingborough and Olney. With the exception of the (former) rectorial lands, it is owned by the Marquess of Northampton *(currently the seventh Marquess) [VCH IV 11, 1937 OUP]. 1.2 It appears that the place name is essentially topographically-derived relative to an “East Farm” perhaps associated with Denton and Whiston lying to the west. The second element is linked to John Maled *(Latin: Maledoctus = dunce) who held the manor in 1166 and whose family name was also being spelt Mauduit (1242) and Maudut (1268). The village name is therefore recorded as having evolved from Eston(e) (1086), Estun (12 th century), through Estone Maudeut (1298), Estone Juxta Boseyate (1305), Eston Mauduyt (1377), to Esson Mawdett in 1611 [Gover, et al]. 1.3 Records of manorial succession commence with William Peverel, the Conqueror’s natural son, and the Countess Judith, his niece, who “held in Estone 2 ½ virgates at the general survey [Whellan].