Soviet Design from Constructivism to Modernism 1920 –1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRACING the Constructlvist INFLUENCES on the BUILDINGS of EKATERINBURG, RUSSIA

BERLIK Ir ACSA EUROPEAN CONFERENCE TRACING THE CONSTRUCTlVIST INFLUENCES ON THE BUILDINGS OF EKATERINBURG, RUSSIA CAROL BUHRMANN University of Kentucky The Sources In the formerly closed Soviet city of Sverdlovsk,now Ekaterinburg, architects undertook a massive building campaign of hundreds of buildings during the Soviet Union's first five year plan, 1928 to 1933. Many of these buildings still exist and in them can be seen the urge to express connections between concept andmaking. These connections were forged from the desire to construct meaningful architectural iconography in the newly formed Soviet Union that would reflect an entirely new social structure. Although a great variety of innovative architecture was being explored in Moscow as early as 1914, it wasn't until the first five year plan that constructivist ideas were utilized extensively throughout the Soviet Union.' Sverdlovsk was to be developed in the 1920s and 1930s as one of the most heavily industrial Fig. 1. Russia. cities in Russia. The construction of vast factories, the expansion of the city, the programming of new workers and the replacement of Czarist and religious memory was supported by an architectural program of constructivist notion that new styles are the product of changing architecture. More buildings were built in Sverdlovsk structural techniques and changing social, functional during this era, per capita, than in either Moscow or requirements. He theorizes that architecture, since Leningrad.L These buildings may reflect more accurately antiquity, expresses itself cyclically: The youth of a new the politics and social climate in the Soviet Union than the style is reflected in "constructive" form, maturity well examined constructivist architecture in both Moscow expressed in organic form and the decay of style is and Leningrad. -

Hidden Cities: Reinventing the Non-Space Between Street and Subway

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway Jae Min Lee University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Jae Min, "Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2984. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2984 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2984 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hidden Cities: Reinventing The Non-Space Between Street And Subway Abstract The connections leading to underground transit lines have not received the attention given to public spaces above ground. Considered to be merely infrastructure, the design and planning of these underground passageways has been dominated by engineering and capital investment principles, with little attention to place-making. This underground transportation area, often dismissed as “non-space,” is a by-product of high-density transit-oriented development, and becomes increasingly valuable and complex as cities become larger and denser. This dissertation explores the design of five of these hidden cities where there has been a serious effort to make them into desirable public spaces. Over thirty-two million urbanites navigate these underground labyrinths in New York City, Hong Kong, London, Moscow, and Paris every day. These in-between spaces have evolved from simple stairwells to networked corridors, to transit concourses, to transit malls, and to the financial engines for affordable public transit. -

Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture, 1915

Press Dossier ”la Caixa” Social Outreach Programmes discovers at CaixaForum Madrid the art and architecture from the 1920s and 30s Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 The Soviet State that emerged from the 1917 Russian Revolution fostered a new visual language aimed at building a new society based on the socialist ideal. The decade and a half that followed the Revolution was a period of intense activity and innovation in the field of the arts, particularly amongst architects, marked by the use of pure geometric forms. The new State required new types of building, from commune houses, clubs and sports facilities for the victorious proletariat, factories and power stations in order to bring ambitious plans for industrialisation to fruition, and operations centres from which to implement State policy and to broadcast propaganda, as well as such outstanding monuments as Lenin’s Mausoleum. Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 illustrates one of the most exceptional periods in the history of architecture and the visual arts, one that is reflected in the engagement of such constructivist artists as Lyubov Popova and Alexander Rodchenko and and Russian architects like Konstantin Melnikov, Moisei Ginzburg and Alexander Vesnin, as well as the European architects Le Corbusier and Mendelsohn. The exhibition features some 230 works, including models, artworks (paintings and drawings) and photographs, featuring both vintage prints from the 1920s and 30s and contemporary images by the British photographer Richard Pare. Building the Revolution. Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 , is organised by the Royal Academy of Arts of London in cooperation with ”la Caixa” Social Outreach Programmes and the SMCA-Costakis Collection of Thessaloniki. -

Russian Architecture

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ КАЗАНСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ АРХИТЕКТУРНО-СТРОИТЕЛЬНЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ Кафедра иностранных языков RUSSIAN ARCHITECTURE Методические указания для студентов направлений подготовки 270100.62 «Архитектура», 270200.62 «Реставрация и реконструкция архитектурного наследия», 270300.62 «Дизайн архитектурной среды» Казань 2015 УДК 72.04:802 ББК 81.2 Англ. К64 К64 Russian architecture=Русская архитектура: Методические указания дляРусская архитектура:Методическиеуказаниядля студентов направлений подготовки 270100.62, 270200.62, 270300.62 («Архитектура», «Реставрация и реконструкция архитектурного наследия», «Дизайн архитектурной среды») / Сост. Е.Н.Коновалова- Казань:Изд-во Казанск. гос. архитект.-строит. ун-та, 2015.-22 с. Печатается по решению Редакционно-издательского совета Казанского государственного архитектурно-строительного университета Методические указания предназначены для студентов дневного отделения Института архитектуры и дизайна. Основная цель методических указаний - развить навыки самостоятельной работы над текстом по специальности. Рецензент кандидат архитектуры, доцент кафедры Проектирования зданий КГАСУ Ф.Д. Мубаракшина УДК 72.04:802 ББК 81.2 Англ. © Казанский государственный архитектурно-строительный университет © Коновалова Е.Н., 2015 2 Read the text and make the headline to each paragraph: KIEVAN’ RUS (988–1230) The medieval state of Kievan Rus'was the predecessor of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine and their respective cultures (including architecture). The great churches of Kievan Rus', built after the adoption of christianity in 988, were the first examples of monumental architecture in the East Slavic region. The architectural style of the Kievan state, which quickly established itself, was strongly influenced by Byzantine architecture. Early Eastern Orthodox churches were mainly built from wood, with their simplest form known as a cell church. Major cathedrals often featured many small domes, which has led some art historians to infer how the pagan Slavic temples may have appeared. -

The Drawn City. Architectural Graphic Art: Tradition and Modernity Sergei Tchoban

4 / 2019 The Drawn City. Architectural Graphic Art: Tradition and Modernity Sergei Tchoban I regard architectural drawing as not just a means of I began drawing very early, at a secondary school speciali- communication, but also an important way to study the zing in art attached to the Academy of Arts in Leningrad. contemporary urban setting. It helps me think about Almost immediately, I realized that my main interest in what architecture is today, in an age when the multi- drawing was architecture. I found all these mises-en-scène vectoral nature of architecture’s development has re- involving cities –not just Leningrad, in which I grew up, but ached its apogee. Drawing is a path to oneself and to also the ancient Russian cities of Novgorod, Rostov Veliky, understanding what is happening around you and what and Pskov– extremely exciting, and the genre of drawing you like in architecture. Here, of course, I cannot entire- with its special agility and incompleteness was the best way ly separate my practice as a draughtsman from my main of translating those internal experiences into artistic image- job: in terms of end result, drawing and architecture are ry. And I have to admit that I have lived all my conscious life very different from one another, but the two types of with this. To this day, I draw a great deal myself – from life, activity are based on reflections on one and the same as well as fantasies that are reflections on the urban envi- subject – how to make cities interesting today, how to ronment, and, of course, sketches for architectural projects. -

SOCIOLOGY of CITY 2019 No 4 СОЦИОЛОГИЯ ГОРОДА

Министерство образования и науки Российской Федерации Волгоградский государственный технический университет SOCIOLOGY OF CITY СОЦИОЛОГИЯ ГОРОДА Sotsiologiya Goroda 2019 no 4 2019 № 4 Scientific-and-theoretical journal Научно-теоретический журнал 4 issues per year Выходит 4 раза в год Учрежден в 2007 г. Year of foundation — 2007 1st issue was published in 2008 1-й номер вышел в 2008 г. г. Волгоград Russian Federation, Volgograd Учредитель: Founders: Федеральное государственное бюджетное Volgograd State Technical University образовательное учреждение (VSTU) высшего образования «Волгоградский государственный технический университет» (ВолгГТУ) Свидетельство о регистрации СМИ ПИ № ФС77-71951 от 13 декабря 2017 г. выдано Федеральной службой по надзору в сфере связи, информационных технологий и массовых коммуникаций (Роскомнадзор) Журнал входит в утвержденный ВАК Минобрнауки России Перечень ведущих рецензируемых научных журналов и изданий, в которых должны быть опубликованы основные научные результаты диссертаций на соискание ученой степени доктора и кандидата наук The journal is included in Russian Science Citation Index (RSCI) Журнал включен в базы данных: (http://www.elibrary.ru), Российского индекса научного Ulrich′s Periodicals Directory цитирования (РИНЦ), http://www.elibrary.ru, (http://serialssolutions.com), Ulrich's Periodicals Directory, http://www.serialssolutions.com, DOAJ (http://www.doaj.org), Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), http://www.doaj.org EBSCO (http://www.ebsco.com) EBSCO, http://www.ebsco.com ISSN 1994-3520. Социология города. 2019. № 4 —————————————————————— Р е д а к ц и о н н ы й с о в е т: E d i t o r i a l c o u n c i l: председатель — д-р техн. наук Chairman — Doctor of Engineering Science И.В. -

Soviet Workers' Clubs

The Journal of Architecture ISSN: 1360-2365 (Print) 1466-4410 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjar20 Soviet workers’ clubs: lessons from the social condensers Anna Bokov To cite this article: Anna Bokov (2017) Soviet workers’ clubs: lessons from the social condensers, The Journal of Architecture, 22:3, 403-436, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2017.1314316 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2017.1314316 Published online: 08 May 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 33 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjar20 Download by: [Cornell University Library] Date: 14 June 2017, At: 02:28 403 The Journal of Architecture Volume 22 Number 3 Soviet workers’ clubs: lessons from the social condensers Anna Bokov School of Architecture, Yale University, USA (Author’s e-mail address: [email protected]) What was a workers’ club? What was its purpose and vision? How did it manifest itself spatially and formally? These are some of the questions that this paper addresses through the historical and architectural analysis of the Soviet workers’ clubs. It looks at the complex phenomenon of the workers’ club from a number of viewpoints. Starting with the idea of club as ‘life itself’, the paper examines it as an instrument of the Proletkult and traces this radically new typology, which aimed to become both a ‘second home’ and a ‘church of a new cult’. It addresses the ideological and educational role of the workers’ club as a ‘school of communism’. -

Moscow – Mel’Nikov the Architecture and Urban Planning of Konstantin Mel’Nikov 1921–1937

Moscow – Mel’nikov The Architecture and Urban Planning of Konstantin Mel’nikov 1921–1937 16th February 2006 to 13th April 2006 Curators: Otakar Máčel (Delft), Maurizio Meriggi (Milan) Dietrich Schmidt (Stuttgart) Press tour: Wednesday, 15th February 2006, 10.30 am Opening: Wednesday, 15th February 2006, 6.30 pm Exhibition venue: Wiener Städtische Allgemeine Versicherung AG Ringturm Exhibition Centre A-1010 Wien, Schottenring 30 Phone: +43 (0)50 350-21115 (Brigitta Fischer) Fax: +43 (0)50 350-99 21115 Opening hours: Monday to Friday: 9.00 am – 6.00 pm; admission free (closed on public holidays) Enquiries: Birgit Reitbauer Phone: +43 (0)50350-21336 Fax: +43 (0)50350-99 21336 e-mail: [email protected] Photographic material is available on our website www.wienerstaedtische.at (in the “Arts & Culture” section) and upon request. The Russian Revolution of October 1917 was followed by a phase of radical artistic and cultural activity that constitutes one of the most interesting periods in 20th-century architecture. Konstantin Mel’nikov made a significant contribution to this exciting period. From deceptively simple exhibition pavilions via his own highly unusual house in the form of a double cylinder to major urban planning projects, his striking architecture is among the most creative of all architectural achievements. ARCHITECTURE IN THE RINGTURM presents a survey of Mel’nikov’s key works in the form of models, photographs and plans. In the 1920s, Konstantin Stepanovich Mel’nikov (Moscow 1890 – Moscow 1974), one of the leading exponents of the Russian avant-garde, developed a revolutionary architectural vision that amounted to nothing less than a new architectonic aesthetic. -

Anticipations of the Ideas of Contemporary Architecture in the Russian Avant-Garde

E3S Web of Conferences 263, 05027 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202126305027 FORM-2021 Anticipations of the Ideas of Contemporary Architecture in the Russian Avant-Garde Oleg Adamov* Moscow State University of Civil Engineering, Yaroslavskoe shosse, 26, Moscow, 129337, Russia Abstract. Leading contemporary architects stated their adherence to the ideas of the Russian Avant-garde that could be “injected” into the Western cultural background and might regenerate or revitalize it. Their approach could be accounted as “superficial sliding”, but quite deep interpenetration to the ideas and images of this culture is also revealed. So the point is, in what ways the inheritance occurs and cross-temporal interaction works in a design culture? The purpose of this paper is to clarify a nature of the multiple links between the working concepts of the masters of the Russian Avant- garde and contemporary Western architects emerging while their creative activity in relation to spatial constructions and affecting the meanings of architectural forms and images. The essay tried to apply the process approach to study the architectural phenomena, treated as a development of structuralism and post-structuralism methods, involving the construction of both synchronic and diachronic models. Comparative analysis of individual ways of designing and creating forms specific to the architects is also used. As a result the individual semantic structures are identified and their interconnections are found out at the different levels of conceptualizing: “picture” imitation and transfiguration; fragmentation; reticulated constructions; cosmos generating; spatial primary units; animated stain; bionic movement; autopoiesis. Tracing the links and transferring the ideas is possible at the meta-level by comparison the whole semantic structures specific for the different times architects, identified by means of reconstruction of their individual creative processes and representation of the broad figurative-semantic fields, referring to the various cultural contexts. -

Argunov 40-49

ТРЕТЬЯКОВСКАЯ ГАЛЕРЕЯ ВЫСТАВКИ Натэлла Войскунская АРХИТЕКТУРНЫЙ ГРИНПИС Выставка В нью-йоркском Музее современного искус- «Потерянный авангард: ства (МОМА) известный фотограф, исследо- советская модернистская ватель мировой архитектуры Ричард Пэйр представил американской публике одну из архитектура. 1922–1932» интереснейших страниц советского архитек- турного модернизма в 75 фотографиях, отоб- ранных из почти 10 тысяч, сделанных им начиная с 1993 года. В организации этой выставки принял участие Фонд содействия сохранению культурного наследия «Русский авангард» во главе с сенатором Сергеем Гордеевым. 3 Шаболовская кспозиция вызвала неподдель- радиобашня. ный интерес и у специалистов, и Ул. Шаболовка, Эу многочисленной разноязыкой Москва. публики, которая буквально «прилипа- Арх. Владимир Шухов. 1922 ла» к огромным цветным фотографиям шедевров советской архитектуры, за 3 Shabolovka Radio немногими исключениями – обшар- Tower. панных, разрушающихся или уже Shabolovka Street, почти полностью разрушенных. Что же Moscow, Russia. Vladimir Shukhov. так задевало неравнодушных зрите- 1922 лей: удивление? восторг? здоровое любопытство? нездоровое любопыт- ство? сострадание к исчезающей нату- ре? интерес к «другой» жизни?.. Видимо, все вместе взятое. Каж- дый снимок сопровождался подроб- ной аннотацией с указанием места и времени создания сооружений и, конечно, сведениями об авторах про- ектов. Описания читали все или почти все посетители выставки. То здесь, то там слышалась русская речь и порой радостные восклицания (как у меня): «Вот соседний дом!» (про московский дом Моссельпрома, построенный в Дом культуры им. С.М.Зуева. 1923–1924 годах Давидом Коганом и Ул. Лесная, 18, Москва. расписанный по макету Александра Арх. Илья Голосов. Родченко) или «Смотри, Азернешр!» – 1926 так бакинцы называли Дом печати, возведенный по проекту Семена Пена Zuev Workers Club. в 1932 году (в нем долгие годы работал 18 Lesnaia Street, Moscow, Russia. -

PRESS RELEASE Temporary Structures in Gorky Park: From

PRESS RELEASE Temporary Structures in Gorky Park: From Melnikov to Ban 20 October – 9 December 2012 Garage Center for Contemporary Culture will present a new exhibition entitled Temporary Structures in Gorky Park: From Melnikov to Ban from 20 October to 9 December 2012 in a newly created temporary pavilion in Moscow’s Gorky Park, designed by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban. Showing rare archival drawings – many of which have never been seen before – the exhibition will begin by revealing the profound history of structures created in the park since the site was first developed in 1923, before moving through the Russian avant-garde period to finish with some of the most interesting contemporary unrealized designs created by Russian architects today. By their nature, temporary structures erected for a specific event or happening have always encouraged indulgent experimentation, and sometimes this has resulted in ground-breaking progressive design. This exhibition recognizes such experimentation and positions the pavilion or temporary structure as an architectural typology that oscillates between art object and architectural prototype. In Russia, these structures or pavilions – often constructed of insubstantial materials – allowed Soviet architects the ability to express the aspirations of the revolution. They frequently became vehicles for new architectural and political ideas, and they were extremely influential within Russian architectural history. This exhibition reveals the rich history of realized and unrealized temporary structures within Moscow’s Gorky Park and demonstrates important stylistic advancements within Russian architecture. Temporary Structures also reveals the evolution of a uniquely Russian ‘identity’ within architecture and the international context, which has developed since the 1920s and continues today. -

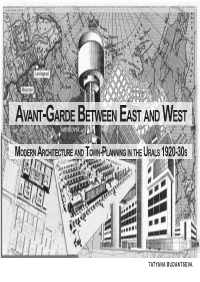

Avant-Garde Between East and West

AVANT-GARDE BETWEEN EAST AND WEST MODERN ARCHITECTURE AND TOWN-PLANNING IN THE URALS 1920-30S TATYANA BUDANTSEVA AVANT-GARDE BETWEEN EAST AND WEST MODERN ARCHITECTURE AND TOWN-PLANNING IN THE URALS 1920-30S Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnifi cus prof. dr. ir. J.T. Fokkema, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 17 december 2007 om 12.30 uur door Tatyana Yevgenyevna BUDANTSEVA architect (Rusland) geboren te Sverdlovsk, Oeral, Rusland Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof. dr. F. Bollerey Toegevoegde promotor: Dr. O. Máčel Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnifi cus, voorzitter Prof. dr. F. Bollerey, Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor Dr. O. Máčel, Technische Universiteit Delft, toegevoegde promotor Prof. dr. M.C. Kuipers, Universiteit Maastricht Prof. dr. V.J. Meyer, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. dr.-ing. B. Kreis, Georg-Simon-Ohm-Fachhochschule Nürnberg, Duitsland Prof. dr. M. Shtiglits, Staats Universiteit voor Architectuur en Bouwkunst, Sankt-Petersburg, Rusland Dr. A. Jäggi, Bauhaus-Archiv Vertaling naar het Engels: Tatyana Budantseva Valentina Grigorieva Dorothy Adams Ontwerp: Tatyana Budantseva © Tatyana Budantseva © Zjoek Publishers ISBN 978-90-812102-2-5 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 9 INTRODUCTION 11 Description of plan, structure and method 14 Selection of the cities 15 Defi nition of the term “constructivism” 15 LITERATURE REVIEW 17 General information on the Modernism