View of the Hand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

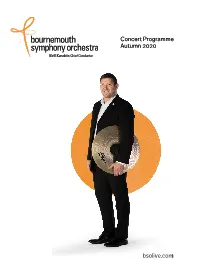

Bsolive.Com Concert Programme Autumn 2020 Bsolive.Com Concert

Concert Programme Autumn 2020 bsolive.com Welcome It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to this What amazing musical portraits Elgar week’s BSO concert of two British created in this dazzling sequence of masterworks, and a gem by Fauré. inventive musical vignettes, for instance, to name but three - the humorous Troyte, the The Britten and Elgar works hold special serious intellect of A.J Jaeger aka ‘Nimrod’, resonances for me. I’d been taken on holiday and the bulldog Dan, the beloved pet of to the Suffolk coast as a child, and when, George Sinclair, organist of Hereford aged fourteen, I first saw Peter Grimes, I was Cathedral, paddling furiously up the river totally bowled over by the power of the Wye. music, and the way it evoked, especially in the Four Sea Interludes, those East Anglican In between, I’m relishing the prospect of the landscapes and coast seascapes that I BSO’s Principal Cello, Jesper Svedberg, remembered. Later, at university in Norwich, bringing his poetic musicianship to Fauré’s I had the privilege of singing under Britten at haunting Élégie. I’m also looking forward to the Aldeburgh Festival, as well as meeting hearing the Britten and Elgar conducted by him at his home, The Red House. For me, David Hill, whose interpretations of English these memories are unforgettable. music are second to none, witnessed, not just in his performances, but also in his Elgar was another discovery of my teens; superb recordings, many, of course, with the when growing up in Birmingham, BSO. Worcestershire and Elgar country was only a couple of hours bus ride away. -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania

Nationalism Through Sacred Chant? Research of Byzantine Musicology in Totalitarian Romania Nicolae GHEORGHIță National University of Music, Bucharest Str. Ştirbei Vodă nr. 33, Sector 1, Ro-010102, Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] (Received: June 2015; accepted: September 2015) Abstract: In an atheist society, such as the communist one, all forms of the sacred were anathematized and fiercly sanctioned. Nevertheless, despite these ideological barriers, important articles and volumes of Byzantine – and sometimes Gregorian – musicological research were published in totalitarian Romania. Numerous Romanian scholars participated at international congresses and symposia, thus benefiting of scholarships and research stages not only in the socialist states, but also in places regarded as ‘affected by viruses,’ such as the USA or the libraries on Mount Athos (Greece). This article discusses the mechanisms through which the research on religious music in Romania managed to avoid ideological censorship, the forms of camouflage and dissimulation of musicological information with religious subject that managed to integrate and even impose over the aesthetic visions of the Party. The article also refers to cultural politics enthusiastically supporting research and valuing the heritage of ancient music as a fundamental source for composers and their creations dedicated to the masses. Keywords: Byzantine musicology, Romania, 1944–1990, socialist realism, totalitari- anism, nationalism Introduction In August 1948, only eight months after the forced abdication of King Michael I of Romania and the proclamation of the people’s republic (30 December 1947), the Academy of Religious Music – as part of the Bucharest Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, today the National University of Music – was abolished through Studia Musicologica 56/4, 2015, pp. -

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ Masterpiece the Pinnacle of a High-Octane Year: Karabits, Montero and More

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ masterpiece the pinnacle of a high-octane year: Karabits, Montero and more 2 October 2019 – 13 May 2020 Kirill Karabits, Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra [credit: Konrad Cwik] EMBARGO: 08:00 Wednesday 15 May 2019 • Kirill Karabits launches the season – his eleventh as Chief Conductor of the BSO – with a Weimar- themed programme featuring the UK premiere of Liszt’s melodrama Vor hundert Jahren • Gabriela Montero, Venezuelan pianist/composer, is the 2019/20 Artist-in-Residence • Concert staging of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and Lighthouse, Poole under the baton of Karabits, with a star-studded cast including Catherine Foster, Allison Oakes and Susan Bullock • The Orchestra celebrates the second year of Marta Gardolińska’s tenure as BSO Leverhulme Young Conductor in Association • Pianist Sunwook Kim makes his professional conducting debut in an all-Beethoven programme • The Orchestra continues its Voices from the East series with a rare performance of Chary Nurymov’s Symphony No. 2 and the release of its celebrated Terterian performance on Chandos • Welcome returns for Leonard Elschenbroich, Ning Feng, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Steven Isserlis, Simone Lamsma, John Lill, Carlos Miguel Prieto, Robert Trevino and more • Main season debuts for Jake Arditti, Stephen Barlow, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Jeremy Denk, Tobias Feldmann, Andrei Korobeinikov and Valentina Peleggi • The Orchestra marks Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, with performances by conductors Kirill Karabits, Sunwook Kim and Reinhard Goebel • Performances at the Barbican Centre, Sage Gateshead, Cadogan Hall and Birmingham Symphony Hall in addition to the Orchestra’s regular venues across a 10,000 square mile region in the South West Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra announces its 2019/20 season with over 140 performances across the South West and beyond. -

ZIYU SHEN, Violist

ZIYU SHEN, violist “Teenager Ziyu Shen is already making her mark on the music scene. Her recital at London’s Royal Festival Hall won a standing ovation.” —Isle of Man Courier “Tonight’s program offered an ideal opportunity to experience this delightful young artist’s prodigious talent. We were treated to a wonderful performance, played superbly.“ —Oberon’s Grove “Besides her flawless technique, Ziyu is very communicative and has a soul of a real artist.” —Gidon Kremer First Prize, 2014 Young Concert Artists International Auditions The Sander Buchman Prize • The University of Florida Performing Arts Prize First Prize, 2013 Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition First Prize, 2012 Chamber Music Competition of Morningside Bridge Chamber Music Competition in Canada First Prize, 2011 Johansen International Competition for Young String Players in Washington, DC YOUNG CONCERT ARTISTS, INC. 1776 Broadway, Suite 1500 New York, NY 10019 Telephone: (212) 307-6655 Fax: (212) 581-8894 [email protected] www.yca.org Photo: Matt Dine Young Concert Artists, Inc. 1776 Broadway, Suite 1500, New York, NY 10019 telephone: (212) 307-6655 fax: (212) 581-8894 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.yca.org ZIYU SHEN, viola 20-year-old violist Ziyu Shen began to play the violin at age of four and switched to the viola at the age of 12 while studying with Li Sheng at the Music School affiliated with the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Among her upcoming concerts, Ms. Shen appears at the PyeongChang Festival, as soloist with the Long Bay Symphony and in recitals at Coastal Carolina University and the Musée du Louvre. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Muzicieni Români În Texte Şi Documente Fondul Constantin Silvestri

MUZICA nr.1/2010 Viorel COSMA Muzicieni români în texte şi documente Fondul Constantin Silvestri Viaţa şi activitatea artistică a compozitorului şi dirijorului Constantin Silvestrei (1913- 1969) a cunoscut două etape, complet diferite: înainte de 1959 (când a avut domiciliul în ţară) şi după 1961 (când s-a stabilit definitiv în străinătate). Materialul documentar din prima perioadă a fost parţial valorificată de Eugen Pricope (în monografia dedicată maestrului, publicată în 1975), în timp ce scrisorile, fotografiile şi sutele de articole din presa străină din ultimul deceniu al vieţii muzicianului au rămas în posesia celei de a doua soţii, Regina-Pupa Silvestri, şi a muzeografului Romeo Drăghici, primul director al Muzeului „George Enescu”. După moartea lui Constantin Silvestri, arhiva s-a risipit, o parte din corespondenţa Silvestri/Drăghici intrând în posesia Arhivelor Istorice de Stat a Municipiului Bucureşti, în timp ce majoritatea cronicilor muzicale şi programelor de sală de la Bournemouth (Anglia) mi-au fost trimise de soţia dirijorului pentru redactarea articolului din lexiconul Muzicieni din România, vol. VIII, 2005. Prin amabilitatea colegului meu Ioan Holender, directorul general al Operei de Stat din Viena, am intrat în posesia unui corpus de texte inedite adresate lui Constantin Silvestri (scrisori de la Mihail Jora, Dinu Lipatti etc.), documente care vor vedea lumina tiparului în revista Muzica, nr. 2/2010. Materialul de faţă se întinde pe o perioadă de peste un sfert de secol (1940-1968), însumând scrisorile adresate lui -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

KEYNOTES the OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER of the EVANSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LAWRENCE ECKERLING, MUSIC DIRECTOR American Romantics

VOL. 46, NO. 3 • MARCH 2015 KEYNOTES THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE EVANSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LAWRENCE ECKERLING, MUSIC DIRECTOR American Romantics he third concert of the ESO’s 69th season, with its 2:30 PM ON Ttheme of the enduring appeal of Romanticism for SUNDAY MARCH 15, 2015 composers well into the 20th century, features three very well known American composers: Copland, Barber, and Hanson, plus a short piece by the Estonian Arvo Pärt. American Romantics Our concert opens with El Salón México by Aaron Copland demanded repayment of $500, which had been advanced (1900–1990). This 12 minute showpiece, premiered in to Barber. Having spent the advance on a European 1936, was the very first of Copland’s “populist” composi- vacation, Barber was forced to have a student at the Curtis tions in which he moved away from his previous Institute of Music perform the finale with only two hours of “modernist” style to an accessible tuneful style. Copland had practice, thereby proving that it was in fact “playable.” discovered the Mexico City dance hall of the title in 1932, ronicallyI perhaps, it is the lush romantic beauty of the first and consulted a collection of Mexican folk songs to lend two movements which has made this concerto the most authentic local color to this brilliantly orchestrated tone performed of all American concertos. picture. Howard Hanson (1896–1981) composed in a style even The austere spirituality of the music of Arvo Pärt provides more consistently Romantic than did Barber; in fact he titled a complete contrast to El Salón México. -

Honegger Y Enescu Piotr Anderszewski Anja Silja

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XX - Nº 198 - Junio 2005 - 6,30 DOSIER Honegger y Enescu ENTREVISTA Piotr Anderszewski Nº 198 - Junio 2005 SCHERZO ENCUENTROS Anja Silja EDUCACIÓN La música en la nueva Ley JAZZ Atomic: Libre y nuclear 9778402 134807 9100 7 AÑO XX Nº 198 Junio 2005 6,30 € 2 OPINIÓN El misterio medieval Santiago Martín Bermúdez 114 Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher CON NOMBRE Josep Pascual 118 PROPIO La obra de una vida 8 Claudio Abbado Harry Halbreich 122 Carmelo Di Gennaro Proteico y descomunal Arturo Reverter 124 10 Pierre Hantaï Pablo J. Vayón Edipo, de la cuna a la tumba Santiago Salaverri 128 12 AGENDA Enescu y Honegger en CD Juan Manuel Viana 132 18 ACTUALIDAD NACIONAL ENCUENTROS Anja Silja 44 ACTUALIDAD Rafael Banús Irusta 142 INTERNACIONAL EDUCACIÓN Pedro Sarmiento 148 60 ENTREVISTA Piotr Anderszewski EL CANTAR DE Bruno Serrou LOS CANTARES Arturo Reverter 150 64 Discos del mes JAZZ SCHERZO DISCOS Pablo Sanz 152 65 Sumario LIBROS 154 DOSIER LA GUÍA 156 113 Honegger y Enescu CONTRAPUNTO Norman Lebrecht 160 Colaboran en este número: Jeffrey Alexander, Javier Alfaya, Julio Andrade Malde, Íñigo Arbiza, Rafael Banús Irusta, Alfredo Brotons Muñoz, José Antonio Cantón, Jacobo Cortines, Carmelo Di Gennaro, Patrick Dillon, Pedro Elías, Fernando Fraga, Ramón García Balado, Manuel García Franco, Joaquín García, José Antonio García y García, Mario Gerteis, José Guerrero Martín, Harry Halbreich, Federico Hernández, Fernando Herrero, Leopoldo Hontañón, Bernd Hoppe, Enrique Igoa, Antonio Lasierra, Norman Lebrecht, Fiona Maddocks, Nadir Madriles, Santiago Martín Bermúdez, Joaquín Martín de Sagarmínaga, Enrique Martínez Miura, Blas Matamoro, Erna Metdepenninghen, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Javier Palacio Tauste, Josep Pascual, Enrique Pérez Adrián, Javier Pérez Senz, Pablo Queipo de Llano Ocaña, Francisco Ramos, Arturo Reverter, Leopoldo Rojas O’Donnell, Stefano Russomanno, Santiago Salaverri, Pablo Sanz, Pedro Sarmiento, Bruno Serrou, Franco Soda, José Luis Téllez, Asier Vallejo Ugarte, Claire Vaquero Williams, Pablo J.