Constantin Silvestri Conducts the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Hiviz Ltd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

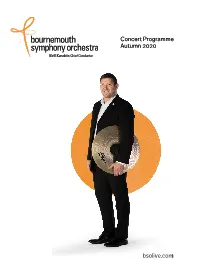

Bsolive.Com Concert Programme Autumn 2020 Bsolive.Com Concert

Concert Programme Autumn 2020 bsolive.com Welcome It’s my great pleasure to welcome you to this What amazing musical portraits Elgar week’s BSO concert of two British created in this dazzling sequence of masterworks, and a gem by Fauré. inventive musical vignettes, for instance, to name but three - the humorous Troyte, the The Britten and Elgar works hold special serious intellect of A.J Jaeger aka ‘Nimrod’, resonances for me. I’d been taken on holiday and the bulldog Dan, the beloved pet of to the Suffolk coast as a child, and when, George Sinclair, organist of Hereford aged fourteen, I first saw Peter Grimes, I was Cathedral, paddling furiously up the river totally bowled over by the power of the Wye. music, and the way it evoked, especially in the Four Sea Interludes, those East Anglican In between, I’m relishing the prospect of the landscapes and coast seascapes that I BSO’s Principal Cello, Jesper Svedberg, remembered. Later, at university in Norwich, bringing his poetic musicianship to Fauré’s I had the privilege of singing under Britten at haunting Élégie. I’m also looking forward to the Aldeburgh Festival, as well as meeting hearing the Britten and Elgar conducted by him at his home, The Red House. For me, David Hill, whose interpretations of English these memories are unforgettable. music are second to none, witnessed, not just in his performances, but also in his Elgar was another discovery of my teens; superb recordings, many, of course, with the when growing up in Birmingham, BSO. Worcestershire and Elgar country was only a couple of hours bus ride away. -

Participating Artists

The Flowers of War – Participating Artists Christopher Latham and in 2017 he was appointed Artist in Ibrahim Karaisli Artistic Director, The Flowers of War Residence at the Australian War Memorial, Muezzin – Re-Sounding Gallipoli project the first musician to be appointed to that Ibrahim Karaisli is head of Amity College’s role. Religion and Values department. Author, arranger, composer, conductor, violinist, Christopher Latham has performed Alexander Knight his whole life: as a solo boy treble in Musicians Baritone – Re-Sounding Gallipoli St Johns Cathedral, Brisbane, then a Now a graduate of the Sydney decade of studies in the US which led to Singers Conservatorium of Music, Alexander was touring as a violinist with the Australian awarded the 2016 German-Australian Chamber Orchestra from 1992 to 1998, Andrew Goodwin Opera Grant in August 2015, and and subsequently as an active chamber Tenor – Sacrifice; Race Against Time CD; subsequently won a year-long contract with musician. He worked as a noted editor with The Healers; Songs of the Great War; the Hessisches Staatstheater in Wiesbaden, Australia’s best composers for Boosey and Diggers’ Requiem Germany. He has performed with many of Hawkes, and worked as Artistic Director Born in Sydney, Andrew Goodwin studied Australia’s premier ensembles, including for the Four Winds Festival (Bermagui voice at the St. Petersburg Conservatory the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs, the Sydney 2004-2008), the Australian Festival of and in the UK. He has appeared with Chamber Choir, the Adelaide Chamber Chamber Music (Townsville 2005-2006), orchestras, opera companies and choral Singers and The Song Company. the Canberra International Music Festival societies in Europe, the UK, Asia and (CIMF 2009-2014) and the Village Building Australia, including the Bolshoi Opera, La Simon Lobelson Company’s Voices in the Forest (Canberra, Scala Milan and Opera Australia. -

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ Masterpiece the Pinnacle of a High-Octane Year: Karabits, Montero and More

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Announce Electrifying 2019/20 Season Strauss’ masterpiece the pinnacle of a high-octane year: Karabits, Montero and more 2 October 2019 – 13 May 2020 Kirill Karabits, Chief Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra [credit: Konrad Cwik] EMBARGO: 08:00 Wednesday 15 May 2019 • Kirill Karabits launches the season – his eleventh as Chief Conductor of the BSO – with a Weimar- themed programme featuring the UK premiere of Liszt’s melodrama Vor hundert Jahren • Gabriela Montero, Venezuelan pianist/composer, is the 2019/20 Artist-in-Residence • Concert staging of Richard Strauss’s opera Elektra at Symphony Hall, Birmingham and Lighthouse, Poole under the baton of Karabits, with a star-studded cast including Catherine Foster, Allison Oakes and Susan Bullock • The Orchestra celebrates the second year of Marta Gardolińska’s tenure as BSO Leverhulme Young Conductor in Association • Pianist Sunwook Kim makes his professional conducting debut in an all-Beethoven programme • The Orchestra continues its Voices from the East series with a rare performance of Chary Nurymov’s Symphony No. 2 and the release of its celebrated Terterian performance on Chandos • Welcome returns for Leonard Elschenbroich, Ning Feng, Alexander Gavrylyuk, Steven Isserlis, Simone Lamsma, John Lill, Carlos Miguel Prieto, Robert Trevino and more • Main season debuts for Jake Arditti, Stephen Barlow, Andreas Bauer Kanabas, Jeremy Denk, Tobias Feldmann, Andrei Korobeinikov and Valentina Peleggi • The Orchestra marks Beethoven’s 250th anniversary, with performances by conductors Kirill Karabits, Sunwook Kim and Reinhard Goebel • Performances at the Barbican Centre, Sage Gateshead, Cadogan Hall and Birmingham Symphony Hall in addition to the Orchestra’s regular venues across a 10,000 square mile region in the South West Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra announces its 2019/20 season with over 140 performances across the South West and beyond. -

Chamberfest Cleveland Announces 2016 Season by Daniel Hathaway

ChamberFest Cleveland announces 2016 season by Daniel Hathaway ChamberFest Cleveland has announced its fifth season under the joint artistic direction of its founders, Cleveland Orchestra principal clarinet emeritus Franklin Cohen and his daughter, Diana Cohen, concertmaster of Canada’s Calgary Symphony. Eleven concerts over fourteen days will be held at venues throughout metropolitan Cleveland from June 16 through July 2. The theme for 2016 is “Tales and Legends.” Concerts will center around stories ranging from the profane to the divine, including the fantastical, mystical, and obsessive. Performers who will join Franklin and Diana Cohen include (to name just a few) pianists Orion Weiss and Roman Rabinovich, violinist/violist Yura Lee, violinist Noah BendixBalgley, and accordionist Merima Ključo, who is composing a piece to be premiered at the festival. The complete schedule is as follows (performers for each event will be announced later). For subscriptions and ticket information, visit the ChamberFest website. Wednesday, June 15 — Nosh at Noon at WCLV’s Smith Studio in Playhouse Square, featuring ChamberFest Cleveland’s 2016 Young Artists (free event). Thursday, June 16 at 8:00 pm — Schumann Fantasies at CIM’s Mixon Hall, 11021 East Blvd. (Openingnight party follows the performance at Crop Kitchen, 11460 Uptown Ave.) Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestucke, Movement from the “F.A.E” Sonata and Piano Quintet, Gyorgy Kurtág’s Hommage à Schumann, and Stephen Coxe’s A Book of Dreams. Friday, June 17 at 8:00 pm — To My Distant Beloved in Reinberger Chamber Hall at Severance Hall (sponsored by The Cleveland Orchestra). Frank Bridge’s Three Songs for MezzoSoprano, Antonín Dvořák’s Cypresses, Gyorgy Kurtág’s One More Voice from Far Away, Ludwig van Beethoven’s To My Distant Beloved, and Johannes Brahms’s Piano Quartet in c. -

The Glorious Violin David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors July 14–August 5, 2017

Music@Menlo CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE The Fifteenth Season: The Glorious Violin David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors July 14–August 5, 2017 REPERTOIRE LIST (* = Carte Blanche Concert) Joseph Achron (1886–1943) Hebrew Dance, op. 35, no. 1 (1913) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Chaconne from Partita no. 2 in d minor for Solo Violin, BWV 1004 (1720)* Prelude from Partita no. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 (arr. Kreisler) (1720)* Double Violin Concerto in d minor, BWV 1043 (1730–1731) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) String Quintet in C Major, op. 29 (1801) Violin Sonata no. 10 in G Major, op. 96 (1812) Heinrich Franz von Biber (1644–1704) Passacaglia in g minor for Solo Violin, The Guardian Angel, from The Mystery Sonatas (ca. 1674–1676)* Ernest Bloch (1880–1959) Violin Sonata no. 2, Poème mystique (1924)* Avodah (1929)* Bluegrass Fiddling (To be announced from the stage)* Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) String Quartet no. 2 in D Major (1881) Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Horn Trio in E-flat Major, op. 40 (1865) String Quartet no. 3 in B-flat Major, op. 67 (1875)* Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) Concerto Grosso in g minor, op. 6, no. 8, Christmas Concerto (1714) Violin Sonata in d minor, op. 5, no. 12, La folia (arr. Kreisler) (1700)* John Corigliano (Born 1938) Red Violin Caprices (1999) Ferdinand David (1810–1873) Caprice in c minor from Six Caprices for Solo Violin, op. 9, no. 3 (1839) Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Petite suite for Piano, Four Hands (1886–1889) Ernő Dohnányi (1877–1960) Andante rubato, alla zingaresca (Gypsy Andante) from Ruralia hungarica, op. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Muzicieni Români În Texte Şi Documente Fondul Constantin Silvestri

MUZICA nr.1/2010 Viorel COSMA Muzicieni români în texte şi documente Fondul Constantin Silvestri Viaţa şi activitatea artistică a compozitorului şi dirijorului Constantin Silvestrei (1913- 1969) a cunoscut două etape, complet diferite: înainte de 1959 (când a avut domiciliul în ţară) şi după 1961 (când s-a stabilit definitiv în străinătate). Materialul documentar din prima perioadă a fost parţial valorificată de Eugen Pricope (în monografia dedicată maestrului, publicată în 1975), în timp ce scrisorile, fotografiile şi sutele de articole din presa străină din ultimul deceniu al vieţii muzicianului au rămas în posesia celei de a doua soţii, Regina-Pupa Silvestri, şi a muzeografului Romeo Drăghici, primul director al Muzeului „George Enescu”. După moartea lui Constantin Silvestri, arhiva s-a risipit, o parte din corespondenţa Silvestri/Drăghici intrând în posesia Arhivelor Istorice de Stat a Municipiului Bucureşti, în timp ce majoritatea cronicilor muzicale şi programelor de sală de la Bournemouth (Anglia) mi-au fost trimise de soţia dirijorului pentru redactarea articolului din lexiconul Muzicieni din România, vol. VIII, 2005. Prin amabilitatea colegului meu Ioan Holender, directorul general al Operei de Stat din Viena, am intrat în posesia unui corpus de texte inedite adresate lui Constantin Silvestri (scrisori de la Mihail Jora, Dinu Lipatti etc.), documente care vor vedea lumina tiparului în revista Muzica, nr. 2/2010. Materialul de faţă se întinde pe o perioadă de peste un sfert de secol (1940-1968), însumând scrisorile adresate lui -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Download Program Notes

ADELAIDE Symphony SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Series 4 SEASON 2021 August Thu 12, Fri 13 & Sat 14 Adelaide Town Hall wwee c caarree a abboouutt yyoouurr ssppeecciiaall mmoommeenntts clcalasssiscic, ,s tsytylilsishh f lfolowweerrss; ; hhaammppeerrss,, ppllaannttss,, && p preremmiuiumm c chhaammppaaggnnee, , wwiinnee aanndd ssppiirriittss ttyynnttee.c.coomm Symphony Thu 12, Fri 13 & Sat 14 Aug Series 4 Adelaide Town Hall Nicholas Braithwaite Conductor Jamie Goldsmith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY [2I] (arr./orch. Ferguson) Pudnanthi Padninthi II – Wadna (‘The Coming and the Going’) Wagner Lohengrin, Act I: Prelude [10I] Mozart Symphony No.35 in D, K.385 Haffner [24I] Allegro con spirito Andante Menuetto – Trio Finale (Presto) Interval Tchaikovsky Symphony No.6 in B minor, Op.74 Pathétique [46I] Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale (Adagio lamentoso – Andante) Duration This concert runs for approximately one hour and 40 minutes, including a 20 minute interval. Listen later This concert will be recorded for later broadcast on ABC Classic. You can hear it again at 1pm on Friday 10 September. The ASO acknowledges that the land we make music on is the traditional country of the Kaurna people of the Adelaide Plains. We pay respect to Elders past and present and recognise and respect their cultural heritage, beliefs and relationship with the land. We acknowledge that this is of continuing importance to the Kaurna people living today. We extend this respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who are with us for this performance today. 3 WELCOME Under current circumstances, it’s almost miraculous to be presenting this concert for you, and to have back with us on the podium one of the great figures in the ASO’s history, Nicholas Braithwaite, who has agreed to step in for Simone Young at very short notice, when border restrictions made it impossible for her to get to Adelaide. -

***** ***** ***** Newsletter 315 June/July

The Richard Wagner Society of South Australia Inc. NEWSLETTER 315 JUNE/JULY 2021 Patron: Deborah Humble We hope our members are all keeping safe, healthy and warm? The situation can change within a day, but we expect that the Society’s next event, the Brian Coghlan Memorial Lecture, will be held on the evening of Monday 9 August at 7.30 pm. in the Clayton Wesley Memorial Church at Beulah Park. For this year’s lecture, James Koehne is to speak on: The Grand Opéra of Paris: The Lost Legacy of the Nineteenth Century Spectacular. We are inviting other groups to this lecture, and some have already promoted it quite widely. Clayton Church, a new venue for the Society, is quite large, but bookings are still required. See P. 2 for details. ***** Wagner’s birthday celebration with a screening of Der Rosenkavalier and lunch at Living Choice Fullarton proved very popular indeed. See the review of that on P.3, along with a couple of other reports. ***** We were hoping to hold at least one other major event later this year, but getting it organised has proved very difficult. However, the Society is obliged to have an Annual General Meeting each year, a pre-Christmas lunch is always popular, and there are plans for a casual event in warmer weather. The dates for these will be announced later. Also, while it’s impossible to be certain, Opera Australia’s Brisbane Ring Cycle will probably still be going ahead in October and November. ***** P1: Next events P4: Tributes P2: Invitation to The Brian Coghlan P5: Article “The Ringheads”. -

SRCD 2345 Book

British Piano Concertos Stanford • Vaughan Williams Hoddinott • Williamson Finzi • Foulds • Bridge Rawsthorne • Ireland Busch • Moeran Berkeley • Scott 1 DISC ONE 77’20” The following Scherzo falls into four parts: a fluent and ascending melody; an oppressive dance in 10/6; a return to the first section and finally the culmination of the movement where SIR CHARLES VILLIERS STANFORD (1852-1924) all the previous material collides and reaches a violent apotheosis. Of considerable metrical 1-3 intricacy, this movement derives harmonically and melodically from a four-note motif. 1st Movement: Allegro moderato 15’39” Marked , the slow movement is a set of variations which unfolds in a 2nd Movement: Adagio molto 11’32” flowing 3/2 time. Inward-looking, this is the concerto’s emotional core, its wistful opening 3rd Movement: Allegro molto 10’19” for piano establishing a mood of restrained lamentation whilst the shattering brass Malcolm Binns, piano motifs introduce a more agonized form of grief, close to raging despair. The cadenza brings London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Nicholas Braithwaite some measure of peace. In the extrovert Finale, the first movement’s orchestration and metres are From SRCD219 ADD c 1985 recalled and the soloist goads the orchestra, with its ebullience restored, towards ever-greater feats of rhythmical dexterity. This typically exultant finale, in modified rondo form, re- GERALD FINZI (1901-1956) affirms the concerto’s tonal centre of E flat. 4 Though technically brilliant, it is the concerto’s unabashed lyricism -

Artes 21-22.Docx

DOI: 10.2478/ajm-2020-0004 Artes. Journal of Musicology Constantin Silvestri, the problematic musician. New press documents ALEX VASILIU, PhD “George Enescu” National University of Arts ROMANIA∗ Abstract: Constantin Silvestri was a man, an artist who reached the peaks of glory as well as the depths of despair. He was a composer whose modern visions were too complex for his peers to undestand and accept, but which nevertheless stood the test of time. He was an improvisational pianist with amazing technique and inventive skills, and was obsessed with the score in the best sense of the word. He was a musician well liked and supported by George Enescu and Mihail Jora. He was a conductor whose interpretations of any opus, particularly Romantic, captivate from the very first notes; the movements of the baton, the expression of his face, even one single look successfully brought to life the oeuvres of various composers, endowing them with expressiveness, suppleness and a modern character that few other composers have ever managed to achieve. Regarded as a very promising conductor, a favourite with the audiences, wanted by the orchestras in Bucharest in the hope of creating new repertoires, Constantin Silvestri was nevertheless quite the problematic musician for the Romanian press. Newly researched documents reveal fragments from this musician’s life as well as the features of a particular time period in the modern history of Romanian music. Keywords: Romanian press; the years 1950; socialist realism. 1. Introduction The present study is not necessarily occasioned by the 50th anniversary of Constantin Silvestri’s death (23rd February 1969).