Early Seleucids, Their Gods and Their Coins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Lecture 9 Hellenistic Kingdoms Chronology

Lecture 9 Hellenistic Kingdoms Chronology: Please see the timeline and browse this website: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/haht/hd_haht.htm Star Terms: Geog. Terms: Ptolemy II Philadelphos Alexandria (Egypt) Apollonius of Rhodes Pergamon (Pergamum) The Museon of Alexandria Antioch The Pharos Lighthouse Red Sea Idylls of Theocritus A. Altar of Zeus (Pergamon, Turkey), c. 175 BCE Attalos I and the Gauls/ gigantomachy/ Pergamon in Asia Minor/high relief/ violent movement Numismatics/ “In the Great Altar of Zeus erected at Pergamon, the Hellenistic taste for emotion, energetic movement, and exaggerated musculature is translated into relief sculpture. The two friezes on the altar celebrated the city and its superiority over the Gauls, who were a constant threat to the Pergamenes. Inside the structure, a small frieze depicted the legendary founding of Pergamon. In 181 BCE Eumenes II had the enormous altar “built on a hill above the city to commemorate the victory of Rome and her allies over Antiochos III the Great of Syria at the Battle of Magnesia (189 BCE) a victory that had given Eumenes much of the Seleucid Empire. A large part of the sculptural decoration has been recovered, and the entire west front of the monument, with the great flight of stairs leading to its entrance, has been reconstructed in Berlin, speaking to the colonial trend of archaeological imperialism of the late 19th century. Lecture 9 Hellenistic Kingdoms B. Dying Gaul, Roman copy of a bronze original from Pergamon, c. 230-220 BCE, marble theatrical moving, and noble representations of an enemy/ pathos/ physical depiction of Celts/Gauls This sculpture is from a monument commemorating the victory in 230 BCE of Attalos I (ruled 241-197 BCE) over the Gauls, a Celtic people who invaded from the north. -

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology (2007)

P1: JzG 9780521845205pre CUFX147/Woodard 978 0521845205 Printer: cupusbw July 28, 2007 1:25 The Cambridge Companion to GREEK MYTHOLOGY S The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology presents a comprehensive and integrated treatment of ancient Greek mythic tradition. Divided into three sections, the work consists of sixteen original articles authored by an ensemble of some of the world’s most distinguished scholars of classical mythology. Part I provides readers with an examination of the forms and uses of myth in Greek oral and written literature from the epic poetry of the eighth century BC to the mythographic catalogs of the early centuries AD. Part II looks at the relationship between myth, religion, art, and politics among the Greeks and at the Roman appropriation of Greek mythic tradition. The reception of Greek myth from the Middle Ages to modernity, in literature, feminist scholarship, and cinema, rounds out the work in Part III. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology is a unique resource that will be of interest and value not only to undergraduate and graduate students and professional scholars, but also to anyone interested in the myths of the ancient Greeks and their impact on western tradition. Roger D. Woodard is the Andrew V.V.Raymond Professor of the Clas- sics and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Buffalo (The State University of New York).He has taught in the United States and Europe and is the author of a number of books on myth and ancient civiliza- tion, most recently Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult. Dr. -

Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus I Soter home : ancient Persia : ancient Greece : Seleucids : index : article by Jona Lendering Antiochus I Soter Antiochus I Soter ('the savior'): name of a Seleucid king, ruled from 281 to 261. Successor of: Seleucus I Nicator Relatives: Father: Seleucus I Nicator Coin of Antiochus I Soter Mother: Apame I, daughter of Spitamenes (Museum of Anatolian Wife: Stratonice I (his stepmother), daughter of Demetrius Civilizations, Ankara) Poliorcetes Children: Seleucus Laodice Apame II (married to Magas of Cyrene) Stratonice II (married to Demetrius II of Macedonia) Antiochus II Theos Main deeds: 301: Present during the Battle of Ipsus 294/293: marriage with his father's wife Stratonice I 292: made co-regent and satrap of Bactria (perhaps Seleucus was thinking of the ancient Achaemenid office of mathišta) Stay in Babylon (on several occasions?), where he showed an interest in the cults of Sin and Marduk, and in the rebuilding of the Esagila and Etemenanki September 281: death of Seleucus (more...); accession of Antiochus; Philetaerus of Pergamon buys back Seleucus' corpse 280-279: Brief war against Ptolemy II Philadelphus (First Syrian War, first part); Cappadocia becomes independent when its leader Ariarathes II and his ally Orontes III of Armenia defeat the Seleucid general Amyntas 279: Intervention in Greece: soldiers sent to Thermopylae to fight against the Galatians; they are defeated 275 Successful "Elephant Battle" against the Galatians; they enter his army as mercenaries; Antiochus is called Soter, 'victor' 274-271: Unsuccessful war against Ptolemy (First Syrian War, second part) 268: Stay in Babylonia; rebuilding of the Ezida in Borsippa 266: Execution of his son Seleucus 263: Eumenes I of Pergamon, successor of Philetaerus, declares himself independent 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Page 1 Antiochus I Soter 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Dies 2 June 261 Succeeded by: Antiochus II Theos Sources: During Antiochus' years as crown prince, he played a large role in Babylonian policy. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 01:02:10PM Via Free Access 332 Chapter 6

chapter 6 Building Urban Community on the Margins: Stratonikeia and the Sanctuary of Zeus at Panamara While Lagina was a local shrine that grew and expanded with Stratonikeia to become its religious center, the sanctuary of Zeus Karios at Panamara was already recognized as an important regional cult center in southern Karia.1 However, it, too, was gradually drawn into the orbit of Stratonikeia to become the next major urban sanctuary of the polis. This case study explores yet another kind of dynamic in the transition to polis sanctuary, one that entailed a major lateral shift in scope for Panamara, from the wider region of southern Karia with diverse communities towards the urban center in the north and its demographic base (Figure 6.1, and Figure 5.1 above). Through an examination of this transition it will become apparent how Stratonikeia came to replace, or absorb, the administering body of the sanctuary, but also how Panamara was used to achieve the same kinds of goals of the emerging polis as was Lagina: territorial integrity, social cohesion, and global recognition, albeit in a different way. Panamara and its environment have unfortunately not been subject to the same systematic archaeological investigations as Lagina, and much of the orig- inal landscape in the area has already been lost in the exploitation of lignite, or brown coal, through strip-mining. Our sources for this sanctuary and its envi- ronment are therefore severely limited, especially with regard to architecture and processional routes. Fortunately, however, the communities involved with the sanctuary at Panamara left hundreds of inscriptions behind that provide valuable insights into the way in which the sanctuary and cult of Zeus Karios were gradually realigned to meet the needs of Stratonikeia. -

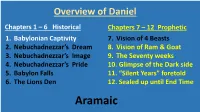

Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8

Overview of Daniel Chapters 1 – 6 Historical Chapters 7 – 12 Prophetic 1. Babylonian Captivity 7. Vision of 4 Beasts 2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 8. Vision of Ram & Goat 3. Nebuchadnezzar’s Image 9. The Seventy weeks 4. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride 10. Glimpse of the Dark side 5. Babylon Falls 11. “Silent Years” foretold 6. The Lions Den 12. Sealed up until End Time Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Babylon Medo- Persia Greece Rome Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Persians Medes Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 8 Greek Empire Alexander The Great Lysimachus Cassander Ptolemy Seleucus Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes The account in 1 Maccabees continues: “Mothers who had allowed their babies to be circumcised were put to death in accordance with the king’s decree. Their babies were hung around their necks, and their families and those who had circumcised them were put to death” (1:60, TEV). ROME 10 11 8 D.T. BEAST 10 HORNS LITTLE HORN ANTI-CHRIST 3 FELL EYES & MOUTH LARGER THAN ASSOCIATES How Long? 2300 evenings & mornings = 167 BC 164 BC Antiochus Antiochus dies sacrificed a pig on the altar Start of Temple Maccabean Rededicated / Revolt cleansed He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.‘ Rev 2:7 Rev 2:11 Rev 2:17 Rev 2:29 Rev 3:6 Rev 3:13 Rev 3:22 To Gorsley in 2011 The Lord is sharpening the focus of the church and wants you to respond: with prayer and fasting and repentance and have ears to hear what the Spirit is saying and hearts and wills to respond to His leading and directing. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter.