Administration, Border Zones and Spatial Practices in the Mekong Subregion Dennis Arnold a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Chantrea Svay Rieng Province Mm

E687 Volume 6 Public Disclosure Authorized Department of Potable Water Supply Ministry of Industry, Mining and Energy (MIME) Phnom Penh, Royal Kingdom of Cambodia Provincial and Peri-Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project, Royal Kingdom of Cambodia Public Disclosure Authorized Initial Environmental Impact Assessment Report Bavet (M07) District of Chantrea Svay Rieng Province Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized mm DRAFT, December 2002 Provincial and Pen-Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Project Initial Environmental Impact Assessment Royal Kingdom of Cambodia (MIME / PPWSA / WB) Bavet (M07), Svay Rieng TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT SUMMARY I INTRODUCTION .......................... 1-1 1 1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ............. .............. ......... ..... 1-1 1 2 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT .............................................. 1-2 1.3 INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................. 1-2 2 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ......................... 2-1 2.1 OBJECTIVES ............................. ................... 2-1 2 2 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION.. ...... ......... .. 2.-.......2-11.................................. 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................ 3-1 3 1 SERVICE AREA .................... ................... .-.......................... 3........3-11.......... 3.2 SUMMARY OF INFRASTRUCTURE . ................................................... .. 3-1 3.3 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS . .3-3 3 4 PROJECT PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION ........ ......................................... 3-3 4 DESCRIPTION -

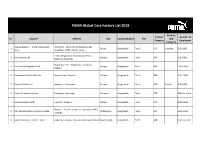

PUMA Global Core Factory List 2019

PUMA Global Core Factory List 2019 Product Product Number of Nr. Supplier Address City Country/Region Tier Sub Category Employees Category Avery Dennison - (Paxar Bangladesh Plot # 167 - 169, DEPZ (Extension Area), 1 Dhaka Bangladesh Tier 2 ACC Labeling 501-1000 Ltd.) Ganakbari, DEPZ, Ashulia, Savar 228/2, Mogorkhal, Dhaka Bipass Road, 2 Eco Couture Ltd. Gazipur Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 501-1000 National University, Begumpur, P.O. : Begumpur, Hotapara, 3 Ever Smart Bangladesh Ltd. Gazipur Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 1001-2000 Gazipur 4 Fakhruddin Textile Mills Ltd. Mouza-kewa, Sreepur Gazipur Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 3501-5000 5 Hamza Textiles Ltd. Nayapara, Kashimpur Gazipur Bangladesh Tier 2 APP Textile 501-1000 6 Jinnat Knitwears Limited Sardagonj, Kashimpur Gazipure Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 5001 or more 7 Mawna Fashions Ltd. Tepirbari, Sreepur Gazipur Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 2001-3500 Plot No. - 7 to 11, Sector - 01, Karnaphuli EPZ, 8 Park (Bangladesh) Company Limited Chattogram Bangladesh Tier 1 ACC 3501-5000 Patenga, 9 Square FashionS Limited - Unit 1 Habir Bari, Valuka, Jamirdia, Habir Bari, Valuka Mymensingh Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 5001 or more Product Product Number of Nr. Supplier Address City Country/Region Tier Sub Category Employees Category Chandana, Basan Union, Dhaka By-Pass Road, 10 Square Fashions Limited -Unit 2 Gazipur Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 3501-5000 Vogra, Gazipur 297, Khortoil,Tongi, DBA - 11 Viyellatex Ltd. Gazipure Bangladesh Tier 1 APP 5001 or more Viyellatex/Youngones Fashion Ltd. National Road No.22, Phum Thnung Roling, 12 Beautiful -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Page 1 of 2 CSEZB

CSEZB - Cambodian Sepecial Economic Zone Board Page 1 of 2 CSEZB - Cambodian Special Economic Zone Board COUNCIL FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF CAMBODIA (CDC) Home CAMBODIAN SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE BOARD (CSEZB) About Us OPERATION AND MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT Country Overview SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE IN CAMBODIA Law & Regulation 1. Neang Kok Koh Kong 1) Company Name Koh Kong SEZ Co.,Ltd CSEZB Structure SEZ Neang Kok Village, Pakkhlong Commune, Investment Guide 2) Location Mundul Seyma Destrict, Koh Kong Province Feedback 3) Land area 335.43 Ha Contact Us 4) Capital N.A 5) Zone Developer Okhna Ly Yong Phat 6) License from CDC No.3399 dated 26 November 2002 7) Sub-Decree No.159 dated 26 October 2007 8) Project Infrastructure Development: Fencing Implementation 1- Camko Motor Company Ltd.: Vehicle 9) Zone Investor Assembly and Spare part Top 2. Suoy Chheng SEZ 1) Company Name Suoy Chheng Investment Co., Ltd. Neang Kok Village, Pakkhlong Commune, 2) Location Mundul Seyma Destrict, Koh Kong Province 3) Land area 100Ha 4) Capital 14 Million 5) Zone Developer Mrs. Kao Suoy Chheng 6) License from CDC No. 3391 dated 26 November 2002 7) Sub-Decree Not yet 8) Project Infrastructure Developing Implementation 9) Zone Investor None Top SNC Lavilin (Cambodia) Holding 3. S.N.C SEZ 1) Company Name Limited Sangkat Bet Trang, Khan Prey Nob , 2) Location Sihanoukville 3) Land area 150 Ha 4) Capital US$14 Million 5) Zone Developer Oknha Kong Triv 6) License from CDC No. 3388 November 26, 2002 7) Sub-Decree Not yet 8) Project http://www.cambodiasez.gov.kh/all_zones_p1.php 7/1/2009 CSEZB - Cambodian Sepecial Economic Zone Board Page 2 of 2 Implementation Infrastructure Developing 9) Zone Investor None Top 4. -

5 November 2009 Łũћŗųњŏ₤΅Юčū˝Ņю₤НЧĠΒЮ₣˛IJ OFFICE of THE

5 November 2009 ŁũЋŗŲњŎ₤΅ЮčŪ˝ņЮ₤ĠΒЮ₣НЧ ˛ij OFFICE OF THE CO-INVESTIGATING JUDGES STATEMENT FROM THE CO-INVESTIGATING JUDGES JUDICIAL INVESTIGATION OF CASE 002/19-09-2007-ECCC-OCIJ AND CIVIL PARTY APPLICATIONS Having received an introductory submission filed by the Co-Prosecutors of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) on 18 July 2007, the Co-Investigating Judges are currently conducting a judicial investigation into allegations of crimes committed by Khieu Samphan, Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary, Ieng Thirith and Kaing Guek Eav (Duch) between 17 April 1975 and 6 January 1979 (Case File 002). As indicated earlier this year, the Co-Investigating Judges reiterate that they are endeavouring to complete the investigation in Case File 002 by the end of 2009. The sixth Plenary Session of the ECCC adopted amendments to the Internal Rules related to the deadline for the filing of Civil Party applications. Pursuant to the amended Internal Rules, anyone who wishes to apply to become a Civil Party must submit an application no later than 15 days after the Co-Investigating Judges have issued the notification that they have concluded the investigation. In order to assist any members of the public who wish to apply to become a Civil Party prior to this deadline and assist in the judicial investigation of Case File 002, the Co-Investigating Judges, pursuant to rule 56.2 a) of the Internal Rules1 hereby provide information outlining the facts falling within the scope of the ongoing investigation. This information should not be seen as a judicial decision as to the scope of the investigation in Case File 2 In the case of an Indictment, the final determination of the material facts sent for trial will be contained in the Closing Order. -

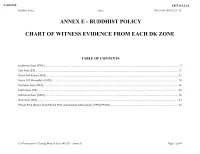

Buddhist Policy Chart of Witness Evidence from Each

ERN>01462446</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC ANNEX E BUDDHIST POLICY CHART OF WITNESS EVIDENCE FROM EACH DK ZONE TABLE OF CONTENTS Southwest Zone [SWZ] 2 East Zone [EZ] 12 Sector 505 Kratie [505S] 21 Sector 105 Mondulkiri [105S] 24 Northeast Zone [NEZ] 26 North Zone [NZ] 28 Northwest Zone [NWZ] 36 West Zone [WZ] 43 Phnom Penh Special Zone Phnom Penh Autonomous Municipality [PPSZ PPAM] 45 ’ Co Prosecutors Closing Brief in Case 002 02 Annex E Page 1 of 49 ERN>01462447</ERN> E457 6 1 2 14 Buddhist Policy Annex 002 19 09 200 7 ECCC TC SOUTHWEST ZONE [SWZ] Southwest Zone No Name Quote Source Sector 25 Koh Thom District Chheu Khmau Pagoda “But as in the case of my family El 170 1 Pin Pin because we were — we had a lot of family members then we were asked to live in a monk Yathay T 7 Feb 1 ” Yathay residence which was pretty large in that pagoda 2013 10 59 34 11 01 21 Sector 25 Kien Svay District Kandal Province “In the Pol Pot s time there were no sermon El 463 1 Sou preached by monks and there were no wedding procession We were given with the black Sotheavy T 24 Sou ” 2 clothing black rubber sandals and scarves and we were forced Aug 2016 Sotheavy 13 43 45 13 44 35 Sector 25 Koh Thom District Preaek Ph ’av Pagoda “I reached Preaek Ph av and I saw a lot El 197 1 Sou of dead bodies including the corpses of the monks I spent overnight with these corpses A lot Sotheavy T 27 of people were sick Some got wounded they cried in pain I was terrified ”—“I was too May 2013 scared to continue walking when seeing these -

Kingdom of Cambodia―

Assigned by Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Base Study on Impact of Population Issue on Agriculture and Rural Development ―KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA― Focus on Phnom Penh and Svay Rieng Province March 2007 The Asian Population and Development Association (APDA) Foreword This report is the product of “Base Study on Impact of Population Issue on Agriculture and Rural Development” consigned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries to Asian Population and Development Association (APDA) in fiscal 2006 and was conducted in the Kingdom of Cambodia. The study and coordination were mainly performed by the domestic review panel created within APDA and headed by Dr. Shigeto Kawano, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo University. Reduction of poverty and starvation as well as securing of sustainability are the pressing challenges included in the U.N. Millennium Development Goals requiring the support of international community and are positioned as priority item in Japan’s ODA Outline. The important tasks are deeply related to population issues including rapid population increase as well as rural-urban and urban-rural migration and various forms of inter-sectoral cooperation are being implemented to address these issues. For this reason, a broad range of information was collected in this study and problems were sorted out with regard to population issues in developing countries in order to propose the policy and points to keep in mind when offering cooperation in the field of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in the future as well as actual ideas of cooperation. I would like to thank Mr. Hor Monirath, Director of Legal and Consular Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation(MFA/IC), and Mr. -

List of SEZ « the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC)

Sitemap Library Links Newsletter Login RSS English 日本語 ែែខររ Click here and enter your keyword... EVENT OF INTEREST Date: 2013-01-23 Cambodia’s 2013 Public Holidays Calendar Date: 2013-01-14 Announcement on the establishment of a Complaints Desk Date: 2013-01-02 Joint Prakas on Public Services at CDC Date: 2012-11-28 Cambodian Investment Seminar in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Date: 2012-11-14 Home About Us Country Overview Laws & Regulations Success Stories Investment Scheme Investor’s Information Investment Yellow Page Home » Special Economic Zones » List of SEZ Welcome to CDC Legal Frame for the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Scheme On behalf of the Incentives Council for the List of SEZ Development of Cambodia, I would like to welcome List of SEZ you. I believe that you are able to COUNCIL FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF CAMBODIA (CDC) acquire the most CAMBODIAN SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE BOARD (CSEZB) Minister attached to current investment the Prime Minister Secretary General, information in this Council for the website. This SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE Development of website represents IN CAMBODIA Cambodia Secretary our continuous General, Cambodian Investment Board endeavors to Name of SEZ Information Secretary General, promote the Cambodian Special development and 1. Neang Kok Koh Kong SEZ1) Location Neang Kok Village, Pakkhlong Commune, Mundul Economic Zone Board investment in Seyma Destrict, Koh Kong Province Cambodia. Read More» 2) Land area 335.43 Ha Statistics 3) Project Implementation Infrastructure Developing: Fencing International Tourist Arrivals to C... The number of international tourists who 1- Camko Motor Company Ltd.: arrived Cambodia as of November 2012 (Vehicle assembly and spare part) reached more than 3 millions, an 4) Zone Investor increase from 2,881,862 recorded in 2-Yazaki Corporation 2011. -

Cambogia=Cambodia=Campucea= Kampuchea=Cambodge=Khmer

CAMBOGIA CAMBOGIA=CAMBODIA=CAMPUCEA= KAMPUCHEA=CAMBODGE=KHMER Roat Kampuchea Regno di Cambogia Phnum Penh=Phnom Penh 400.000 ab. Kmq. 181.035 (178.035)(181.000)(181.040) Compreso Kmq. 3.000 di acque interne Dispute con Tailandia per: - Territorio di Preah Vihear (occupato Cambogia) - Poi Pet Area (occupato Tailandia) - Buri=Prachin Buri Area (occupato Tailandia). Dispute con Vietnam per: - Cocincina Occidentale e altri territori (occupati Vietnam) - alcune isole (occupate Vietnam): - Dak Jerman=Dak Duyt - Dak Dang=Dak Huyt - La Drang Area - Baie=Koh Ta Kiev Island - Milieu=Koh Thmey Island - Eau=Koh Sep Island - Pic=Koh Tonsay Island - Northern Pirates=Koh Po Island Rivendica parte delle Scarborough Shoals (insieme a Cina, Taivan, Vietnam, Corea, Malaisia, Nuova Zelanda). Dispute con Tailandia per acque territoriali. Dispute con Vietnam per acque territoriali. Movimento indipendentista Hmon Chao Fa. Movimento indipendentista Khmer Krom. Ab. 7.650.000---11.700.000 Cambogiani=Cmeri=Khmer (90%) - Cmeri Candali=Khmer Kandal=Cmeri Centrali=Central Khmers (indigeni) - Cmeri Cromi=Khmer Krom (cmeri insediati nella Cambogia SE e nel Vietnam Meridionale) - Cmeri Surini=Khmer Surin (cmeri insediati nella Cambogia NO e nelle province tailandesi di Surin, Buriram, Sisaket - Cmeri Loeu=Cmeri Leu=Khmer Loeu (termine ombrello per designare tutte le tribù collinari della Cambogia)(ca. 100.000 in tutto): - Parlanti il Mon-Cmero=Mon-Khmer (94%) - Cacioco=Kachok - Crungo=Krung - Cui=Kuy - Fnongo=Phnong - Tampuano=Tampuan (nella provincia di Ratanakiri NE) -

Cambodia Municipality and Province Investment Information

Cambodia Municipality and Province Investment Information 2013 Council for the Development of Cambodia MAP OF CAMBODIA Note: While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this publication is accurate, Japan International Cooperation Agency does not accept any legal responsibility for the fortuitous loss or damages or consequences caused by any error in description of this publication, or accompanying with the distribution, contents or use of this publication. All rights are reserved to Japan International Cooperation Agency. The material in this publication is copyrighted. CONTENTS MAP OF CAMBODIA CONTENTS 1. Banteay Meanchey Province ......................................................................................................... 1 2. Battambang Province .................................................................................................................... 7 3. Kampong Cham Province ........................................................................................................... 13 4. Kampong Chhnang Province ..................................................................................................... 19 5. Kampong Speu Province ............................................................................................................. 25 6. Kampong Thom Province ........................................................................................................... 31 7. Kampot Province ........................................................................................................................ -

Ministry of Commerce ្រពឹត ិប្រតផ ូវក រ សបា ហ៍ទី ៤៧-៥១

䮚ពះ楒ᾶ㮶ច䮚កកម�ុᾶ ᾶតិ 絒ស侶 䮚ពះម腒ក䮟䮚ត KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA NATION RELIGION KING 䮚កសួង奒ណិជ�កម� 侶យក⥒�នកម�សិទ�ិប�� MINISTRY OF COMMERCE Department of Intellectual Property 䮚ពឹត�ិប䮚តផ�ូវŒរ OFFICIAL GAZETTE ស厶� ហ៍ទី ៤៧-៥១ ៃន᮶�ំ ២០២០ Week 47-51 of 2020 18/Dec/2020 (PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY) ែផ�កទី ១ PP AA RR TT II ការចុះប��ីថ�ី NNEEWW RREEGGIISSTTRRAATTIIOONN FFRROOMM RREEGG.. NNoo.. 7788992244 ttoo 7799991122 PPaaggee 11 ttoo 333377 ___________________________________ 1- េលខ⥒ក់奒ក䮙 (APPLICATION No. ) 2- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙 (DATE FILED) 3- 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក (NAME OF APPLICANT) 4- 襒សយ⥒�ន掶�ស់掶៉ក (ADDRESS OF APPLICANT) 5- 䮚បេទស (COUNTRY) 6- េ⅒�ះ徶�ក់ᅒរ (NAME OF AGENT) 7- 襒សយ⥒�ន徶�ក់ᅒរ (ADDRESS OF AGENT) 8- េលខចុះប��ី (REGISTRATION No) 9- Œលបរិេច�ទចុះប��ី (DATE REGISTERED) 10- គំរ ូ掶៉ក (SPECIMEN OF MARK) 11- ជពូកំ (CLASS) 12- Œលបរ ិេច�ទផុតកំណត់ (EXPIRY DATE) ែផ�កទី ២ PP AA RR TT IIII RREENNEEWWAALL PPaaggee 333388 ttoo 445522 ___________________________________ 1- េលខ⥒ក់奒ក䮙េដម (ORIGINAL APPLICATION NO .) 2- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙េដម (ORIGINAL DATE FILED) 3- (NAME OF APPLICANT) 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក 4- 襒 ស យ ⥒� ន 掶� ស 掶៉់ ក (ADDRESS OF APPLICANT) 5- 䮚បេទស (COUNTRY) 6- េ⅒�ះ徶�ក់ᅒរ (NAME OF AGENT) 7- 襒សយ⥒�ន徶�ក់ᅒរ (ADDRESS OF AGENT) 8- េលខចុះប��េដ ី ម (ORIGINAL REGISTRATION No) 9- Œលបរ ិេច�ទចុះប��ីេដម ORIGINAL REGISTRATION DATE 10- គ ំរ 掶៉ ូ ក (SPECIMEN OF MARK) 11- ំ (CLASS) ជពូក 12- Œលបរ ិេច�ទ⥒ក់奒ក䮙សំ◌ុចុះប��ី絒ᾶថ� ី (RENEWAL FILING DATE) 13- Œលបរ ិេច�ទចុះប��ី絒ᾶថ� ី (RENEWAL REGISTRATION DATE) 14- Œលបរ ិេច�ទផុតកំណត់ (EXPIRY DATE) ែផ�កទី ៣ PP AA RR TT IIIIII CHANGE, ASSIGNMENT, MERGER -

A Short History of Cambodia.Pdf

Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page i CAMBODIAA SHORT HISTORY OF Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Other books in the series Short History of Bali, Robert Pringle Short History of China and Southeast Asia, Martin Stuart-Fox Short History of Indonesia, Colin Brown Short History of Japan, Curtis Andressen Short History of Laos, Grant Evans Short History of Malaysia, Virginia Matheson Hooker Series Editor Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of many books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An introductory history, first published in 1979 and now in its ninth edition, and The Mekong: Turbulent past, uncertain future, published in 2000. Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF CAMBODIA FROM EMPIRE TO SURVIVAL By John Tully Short History of Cambodia 10/3/06 1:57 PM Page iv First published in 2005 by Allen & Unwin Copyright © John Tully 2005 Maps by Ian Faulkner All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.