Prolegomena 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

Bowl Round 2 Bowl Round 2 First Quarter

NHBB A-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 2 Bowl Round 2 First Quarter (1) Emperor Wu Di of Han placed a monopoly on salt and this material. A pillar of this material was signed by King Chandra and notoriously resists corrosion. The Hittites created artifacts of this material. Abraham Darby created a method to create the \pig" type of this substance using coke instead of charcoal. and its \wrought" form was used to construct the Eiffel Tower. For ten points, name this metal whose use ended the Bronze Age. ANSWER: iron (2) During Europe's industrial era, the most popular history of this country was an account by botanist Engelbert Kaempfer. The 26 martyrs were crucified in this country. After the San Felipe was shipwrecked near this country, its leader closed off most of its ports to Spanish and Portuguese missionaries and forced its Christian population to become Kakure [ka-koo-ray], or hidden. For ten points, name this country where Christianity once flourished around Nagasaki. ANSWER: Japan (3) William Thomas Turner attempted to prevent this disaster, which occurred near the Old Head of Kinsale. The Cunard Company was prosecuted for its negligence surrounding this event, since it failed to reveal that munitions had been placed in storage. William Jennings Bryan resigned as Secretary of State because he felt Woodrow Wilson was too strong-handed in his reaction to, for ten points, what 1915 event in which a British ocean liner was torpedoed by a German U-boat? ANSWER: sinking of (or attack on, etc.) the RMS Lusitania (4) Charles Weir invented a device that uses this mineral to compress materials to extremely high pressures. -

A Case Study on the Two Turkısh Translatıons of Paul Auster's Cıty Of

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 iii ÖZET HÜYÜKLÜ, İpek. Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent adlı Eserinin İki Çevirisi üzerine bir Çalışma. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, 2015. Bu çalışmanın amacı, Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde çevirmene zorluk yaratacak öğelerin çevirmenler tarafından nasıl çevrildiğini Venuti’nin yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma kavramları ışığı altında analiz ederek çevirmenlerin uyguladıkları stratejileri tespit etmektir. Bunun yanı sıra Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünürlüğü ve görünmezliği yaklaşımları temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu ortaya koymak amaçlanmıştır. Bu amaç doğrultusunda, çevirmenler için zorluk yaratan öğelerin sıklıkla kullanıldığı ve postmodern biçemiyle bilinen Paul Auster’a ait Cam Kent adlı eserin Yusuf Eradam (1993) ve İlknur Özdemir (2004) tarafından Türkçe’ye yapılan iki farklı çevirisi analiz edilmiştir. Bu eserin çevirisini zorlaştıran faktörler; özel isimler, kelime oyunları, bireydil, dilbilgisel normlar, tipografi, gönderme ve yabancı sözcükler olmak üzere yedi başlık altında toplanmış olup Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde tercih edilen çeviri stratejileri karşılaştırılmıştır. Bu karşılaştırma, Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünmezliği yaklaşımı temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu incelemek üzere yapılmıştır. İki çevirinin karşılaştırmalı analizinin ardından, iki çevirmenin de farklı öğeler için yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma yaklaşımlarını bir çeviri stratejisi olarak kullandığı sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

Workshop Leaders and Speakers

WORKSHOP LEADERS AND SPEAKERS Arabic to English group: Jonathan Wright Jonathan Wright is a British journalist and literary translator. He joined Reuters news agency in 1980 as a correspondent, and has been based in the Middle East for most of the last three decades. He has served as Reuters' Cairo bureau chief, and he has lived and worked throughout the region, including in Egypt, Sudan, Lebanon, Tunisia and the Gulf. From 1998 to 2003, he was based in Washington, DC, covering U.S. foreign policy for Reuters. For two years until the fall of 2011 Wright was editor of the Arab Media & Society Journal, published by the Kamal Adham Center for Journalism Training and Research at the American University in Cairo. Elisabeth Jaquette Elisabeth Jaquette is a translator from the Arabic and Executive Director of the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA). Her work has been shortlisted for the TA First Translation Prize, longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award, and supported by several English PEN Translates Awards, a Jan Michalski Foundation residency, and the PEN/Heim Translation Fund. She has also served as a judge for numerous translation prizes, including most recently the National Book Award for Translated Literature. Elisabeth’s book-length translations include The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz (Melville House), Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun (Comma Press), and The Apartment in Bab el-Louk by Donia Maher (Darf Publishers). Forthcoming in 2020 are The Frightened Ones by Dima Wannous (Harvill Secker/Knopf) and Minor Detail by Adania Shibli (Fitzcarraldo/New Directions). English to Arabic group: Boutheina Khaldi Boutheina Khaldi is Associate professor of Arabic and translation studies at the American University of Sharjah. -

The Tin Drum by Günter Grass « « HMH Book Clubs HMH Bo

The Tin Drum by Günter Grass « « HMH Book Clubs HMH Bo... http://hmhtrade.com/bookclubs/discussion-guides/the-tin-drum-... HMH Book Clubs Find great new books for your reading group! The Tin Drum by Günter Grass 20 May 2010, 1:31 pm A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE TEACHER The Tin Drum, without question one of the landmark novels of the twentieth century, was originally published in English in Ralph Manheim’s outstanding translation. It was a huge bestseller; it almost instantly made its young author a major figure in world literature. This fiftieth anniversary edition, newly translated by Breon Mitchell, is more faithful to Günter Grass’s style and rhythm, restores many omissions, and reflects more fully the complexity of the original work. As he relates in his thorough Translator’s Afterword, Mitchell has created this new Tin Drum under the careful guidance, and with the close and willing cooperation, of Grass himself. “It is precisely the mark of a great work of art that it demands to be retranslated,” notes Mitchell. “We translate great works because they deserve it — because the power and depth of the text can never be fully realized by a single translation, no matter how inspired.” Now, after half a century, and in Mitchell’s capable hands, The Tin Drum has lost none of its original “power and depth,” its strength and relevance, its epic majesty. The vast, sweeping account of Oskar Matzerath, whose life story also functions as the story of modern Germany itself, is as rich and evocative as ever before. -

An Analysis Of" City of Glass" by Paul Auster in Terms of Postmodernism

International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 5, Issue 1, April 2017, p. 478-486 Received Reviewed Published Doi Number 17.01.2017 16.02.2017 24.04.2017 10.18298/ijlet.1659 AN ANALYSIS OF CITY OF GLASS BY PAUL AUSTER FROM A POSTMODERNIST PERSPECTIVE1 Mehmet Cem ODACIOĞLU 2 & Chek Kim LOI3 & Fadime ÇOBAN4 ABSTRACT This study analyzes City of Glass, a postmodernist detective novella (or anti-detective) of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster in terms of postmodernist elements and techniques such as metafiction, parody, intertextuality, irony. In doing so, some information about Auster’s life and the plot of the work are also offered to the reader to make the analysis more concrete. Last but not least, this study is also thought to be useful for students enrolled in English Language and Literary Departments for them to understand the movement of postmodernism. Key Words: City of Class, postmodernist detective fiction, anti-detective, metafiction, parody, irony, intertextuality, pastiche. 1.Short Biography of Paul Auster Paul Auster is an American-Jewish essayist, novelist, translator, poet, screenwriter and memoirist, who was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 3, 1947. Auster lived in a middle class family and spent some of his childhood in the Newark suburbs of South Orange and Maplewood. However, in 1959, his family moved into a large Tudor house. Auster's uncle, Allen Mandelbaum was a translator and left his books for him to read there when he decided to make a journey to Europe. Auster read all of these books which encouraged him to be interested in writing and in literature. -

Logic Intertextuality in the Works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Reading to you, or the aesthetics of marriage : dia- logic intertextuality in the works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40315/ Version: Full Version Citation: Williamson, Alexander (2018) Reading to you, or the aesthet- ics of marriage : dialogic intertextuality in the works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 Reading to You, or the Aesthetics of Marriage Dialogic Intertextuality in the Works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster Alexander Williamson Doctoral thesis submitted in partial completion of a PhD at Birkbeck, University of London July 2017 2 Abstract Using a methodological framework which develops Vera John-Steiner’s identification of a ‘generative dialogue’ within collaborative partnerships, this research offers a new perspective on the bi-directional flow of influence and support between the married authors Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster. Foregrounding the intertwining of Hustvedt and Auster’s emotional relationship with the embodied process of aesthetic expression, the first chapter traces the development of the authors’ nascent identities through their non-fictional works, focusing upon the autobiographical, genealogical, canonical and interpersonal foundation of formative selfhood. Chapter two examines the influence of postmodernist theory and poststructuralist discourse in shaping Hustvedt and Auster’s early fictional narratives, offering an alternative reading of Auster’s work outside the dominant postmodernist label, and attempting to situate the hybrid spatiality of Hustvedt and Auster’s writing within the ‘after postmodernism’ period. -

Notes On/In Paul Auster's Oracle Night

RSA Journal 14/2003 PIA MASIERO MARCOLIN Notes on/in Paul Auster's Oracle Night Encountering a footnote is like going downstairs to answer the doorbell while making love. Noel Coward I tried to use certain genre conventions to get to another place, another place altogether. Paul Auster Paul Auster's twelfth novel, Oracle Night, is the account of nine days in the life of Sidney Orr told by himself twenty years later. The nine days, starting "on the morning in question — September 18, 1982— " (189) span a (retrospectively) crucial moment in the life of the protagonist/narrator who, while recovering from a near-fatal illness is won back to his job — writing — by a close friend of his, the acclaimed writer John Trause, and by the spellbinding power of a newly acquired blue Portuguese notebook. John Trause (and the new notebook) intrigues him into trying to write a variation of an episode in Hammett's The Maltese Falcon in which a man walks away from his wife and disappears after going through a near-death experience. Almost halfway through the book, the novel progresses on a double track: on the one hand, Sidney Orr's therapeutic walks, his everyday life with his beloved wife Grace and his friend John, and on the other, Nick Bowen's story, his flight to Kansas City, his friendship with a retired taxi-driver, Ed, whom he helps in the heavy 182 Pia Masiero Marcolin job of reorganizing his collection of phone-books in a deserted underground warehouse in which he eventually gets trapped. -

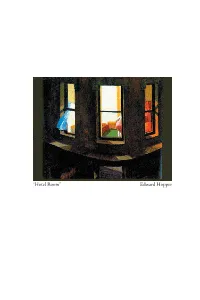

Edward Hopper the Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster

“Hotel Room” Edward Hopper The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster James Peacock University of Edinburgh Auster contributed an extract from Moon Palace to the collection “Edward Hopper and the American Imagination,” and it is clear that Hopper’s images of alienated individuals have had a profound resonance for him. This paper employs two main ideas to compare them. First, a pivotal moment in American literature: the hotel room drama watched by Coverdale in Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance. Secondly, Aby Warburg’s concept of the “pathos formula” in art, which bypasses the problematic issue of influence, choosing instead to posit sets of inherited cultural memories. It therefore allows discussion of the re-emergence of Hawthorne’s puritan tropes of paranoid specularity and transcendence in the work of Hopper and Auster. I was never able to paint what I set out to paint. (Edward Hopper, quoted in O’Doherty 77) Words are transparent for him, great windows that stand between him and the world, and until now they have never impeded his view, have never even seemed to be there. (G 146) Somewhere in New England in the nineteenth century, a man resumes his “post” (Hawthorne 168) at his hotel room window, there to observe the boarding house opposite. Before long, a “knot of characters” enters one of the rooms, appearing before our observer as if projected onto the physi- cal stage, having been “kept so long upon my mental stage, as actors in a drama.” Longing for “a catastrophe,” some moment of high theatre to fill the epistemological void of his own soul, our voyeur gazes with increasing intensity, fabricating scenarios which, he admits, “might have been alto- gether the result of fancy and prejudice in me.” When, in one of the most compelling and influential moments in all American literature, he is spot- ted by the female protagonist and barred from the scene by the dropping of a curtain, his appetite for narrative resolution remains unsated and he is condemned to brood on his isolation once more. -

Spring / Summer 2015

ND SPRING / SUMMER 2015 -I- WINTER 2015 MAY JUNE JULY CONTENT`S Carson, Anne Antigonick ......................... 3 Hoffmann, Yoel Moods ............................. 5 Keene, John Counternarratives .................... 1 Lispector, Clarice The Complete Stories ............... 11 Mackey, Nathaniel AUGUST Blue Fasa .......................... 2 Ross, Fran Oreo .............................. 8 Tanizaki, Junichiro A Cat, a Man & Two Women ......... 13 Vila-Matas, Enrique A Brief History of Portable Literature .... 7 The Illogic of Kassel ................. 6 West, Nathanael The Day of the Locust ................ 4 Yousufi, Mushtaq Ahmed Mirages of the Mind . 9 John Keene Counternarratives • African-American Literature • Author Appearances Conjuring slavery and witchcraft, and with bewitch- ing powers all its own, Counternarratives continu- ally spins history—and storytelling—on its head Ranging from the 17th century to the present and crossing multiple continents, Counternarratives’ novellas and stories draw upon memoirs, newspaper ac- CLOTH counts, detective stories, interrogation transcripts, and speculative fiction to create new and strange perspectives on our past and present. In “Rivers,” a FICTION MAY free Jim meets up decades later with his former raftmate Huckleberry Finn; “An Outtake” chronicles an escaped slave’s fate in the American Revolution; “On 5" X 8" 320pp Brazil, or Dénouement” burrows deep into slavery and sorcery in early colonial South America; and in “Blues” the great poets Langston Hughes and Xavier ISBN 978-0-8112-2434-5 Villaurrutia meet in Depression-era New York and share more than secrets. EBK 978-0-8112-2435-2 PRAISE FOR ANNOTATIONS 24 CQ TERRITORY A “Genius—brilliant, polished and of considerable depth.” —ISHMAEL REED US $24.95 CAN $27.95 “A masterpiece.” —JEANNIE VANASCO, TIN HOUSE “Annotations is worthy of the highest recommendation. -

Bibliografía De Camilo José Cela

BIBLIOGRAFÍA DE CAMILO JOSÉ CELA LIBROS* Cachondeos, escarceos y otros meneos. Madrid: Temas de Hoy, 2001 Café de artistas y otros papeles volanderos. Murcia: Bibliotex, 1998 Correspondencia con el exilio. Barcelona: Destino, 2009 Cristo versus Arizona. Bucuresti: Libra, 1997 Cuaderno del Guadarrama. Madrid: Real Sociedad Española de Alpinismo Peñalara, 2002 Del Miño al Bidasoa. Navarra: Editorial Leer-e, 2010 Diccionario geográfico popular de España. Madrid: Noesis, 1998 El espejo y otros cuentos. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 2000 El gallego y su cuadrilla. Barcelona: Destino, 1997 El gallego y su cuadrilla y otros apuntes carpetovetónicos. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1999 Elogio del vino. Logroño: Gobierno de La Rioja, Cosejería de Agricultura, Ganadería y Desarrollo Rural, 1998 Historias familiares. Barcelona: Macià & Nubiola, 1998 Imposición del título de Doctor Honoris Causa a Don Camilo José Cela. 1998 Judíos, moros y cristianos. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1999 La catira. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1999 La colmena. Barcelona: Destino, 2008 La colmena. Pozuelo de Alarcón Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 2007 La colmena. Madrid: Castalia, 2007 La colmena. Madrid: Club Internacional del Libro, 2007 La colmena. Villafranca del Castillo Madrid: Universidad Camilo José Cela, 2005 La colmena. Madrid: El País, 2005 La colmena. Madrid: Mare Nostrum, 2005 La colmena. Barcelona: Debolsillo, 2003 La colmena. Barcelona: RBA, 2003 La colmena. Barcelona: Planeta-De Agostini, 2003 La colmena. Barcelona: Sol 90, 2003 La colmena. Barcelona: Vicens-Vives, 2002; 1996 La colmena. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg Círculo de Lectores, 2002 La colmena. Madrid: Edaf, 2002 Instituto Cervantes. Departamento de Bibliotecas y Documentación. Página 1 La colmena. Madrid: Cátedra, 2000 La colmena. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés, 1999 La colmena.