To My Father, Nüsret SADIGBEYLİ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2

No. 86 25 July 2016 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html TURKISH SOCIETAL ACTORS IN THE CAUCASUS Special Editors: Andrea Weiss and Yana Zabanova ■■Introduction by the Special Editors 2 ■■Track Two Diplomacy between Armenia and Turkey: Achievements and Limitations 3 By Vahram Ter-Matevosyan, Yerevan ■■How Non-Governmental Are Civil Societal Relations Between Turkey and Azerbaijan? 6 By Hülya Demirdirek and Orhan Gafarlı, Ankara ■■Turkey’s Abkhaz Diaspora as an Intermediary Between Turkish and Abkhaz Societies 9 By Yana Zabanova, Berlin ■■Turkish Georgians: The Forgotten Diaspora, Religion and Social Ties 13 By Andrea Weiss, Berlin ■■CHRONICLE From 14 June to 19 July 2016 16 Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2 Introduction by the Special Editors Turkey is an important actor in the South Caucasus in several respects: as a leading trade and investment partner, an energy hub, and a security actor. While the economic and security dimensions of Turkey’s role in the region have been amply addressed, its cross-border ties with societies in the Caucasus remain under-researched. This issue of the Cauca- sus Analytical Digest illustrates inter-societal relations between Turkey and the three South Caucasus states of Arme- nia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, as well as with the de-facto state of Abkhazia, through the prism of NGO and diaspora contacts. Although this approach is by necessity selective, each of the four articles describes an important segment of transboundary societal relations between Turkey and the Caucasus. -

The Caucasus Globalization

Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 1 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies Conflicts in the Caucasus: History, Present, and Prospects for Resolution Special Issue Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 CA&CC Press® SWEDEN 2 Volume 6 Issue 2 2012 FOUNDEDTHE CAUCASUS AND& GLOBALIZATION PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES OF THE CAUCASUS Registration number: M-770 Ministry of Justice of Azerbaijan Republic PUBLISHING HOUSE CA&CC Press® Sweden Registration number: 556699-5964 Registration number of the journal: 1218 Editorial Council Eldar Chairman of the Editorial Council (Baku) ISMAILOV Tel/fax: (994 12) 497 12 22 E-mail: [email protected] Kenan Executive Secretary (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Azer represents the journal in Russia (Moscow) SAFAROV Tel: (7 495) 937 77 27 E-mail: [email protected] Nodar represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) KHADURI Tel: (995 32) 99 59 67 E-mail: [email protected] Ayca represents the journal in Turkey (Ankara) ERGUN Tel: (+90 312) 210 59 96 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Board Nazim Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) MUZAFFARLI Tel: (994 – 12) 510 32 52 E-mail: [email protected] (IMANOV) Vladimer Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Georgia) PAPAVA Tel: (995 – 32) 24 35 55 E-mail: [email protected] Akif Deputy Editor-in-Chief (Azerbaijan) ABDULLAEV Tel: (994 – 12) 596 11 73 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 6 IssueMembers 2 2012 of Editorial Board: 3 THE CAUCASUS & GLOBALIZATION Zaza D.Sc. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Turkish President Turgut Özal's Impact on Nursultan

TURKISH PRESIDENT TURGUT ÖZAL’S IMPACT ON NURSULTAN NAZARBAYEV’S PERCEPTION OF TURKEY* Nursultan Nazarbayev'ın Türkiye Algısına Tugut Özal'ın Etkisi Din Muhammed AMETBEK** Abstract Nursultan Nazarbayev as the founding President of Kazakhstan played a determinant role in the formation of Kazakh foreign policy. In this respect, the article examines Nazarbayev’s perception of Turkey as a decision maker in foreign policy are based on observation rather than realities. Nazarbayev is aware of the fact that the national identity of Kazakhstan is divided between two competing poles; Russian and Kazakh, in a broader sense; Slavic and Turkic. From this perspective, Nazarbayev’s perception of Turkey is significant as it is not only related to foreign policy but at the same time the national identity of Kazakhstan. The study argues that the President of Republic of Turkey of early 1990s Turgut Özal with his active diplomacy towards Kazakhstan contributed to the positive image of Turkey. The research concludes that close and reliable relations between Nazarbayev and Özal became the basis of a strategic part- nership between Kazakhstan and Turkey. Keywords: Turgut Özal, Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Perception, National Identity Özet Kazakistan’ın kurucu Cumhurbaşkanı Nursultan Nazarbayev’in, Kazak dış politi- kasının oluşumunda belirleyici rol üstlendiği kesindir. Bu bağlamda, makale, Nazarba- yev’in Türkiye algısını ele almaktadır. Çünkü inşacı ekolün iddiasına dış politika kararları gerçeklere değil algı üzerine alınmaktadır. Nazarbayev Kazakistan’ın ulusal kimliğinin Rus ve Kazak olarak, daha geniş kapsamda Slav ve Türk olarak yarışan iki kutba ayrıldığının farkındadır. Buradan hareketle, Nazarbayev’in Türkiye algısı, yal- nızca dış politika açısından değil aynı zamanda Kazakistan’ın ulusal kimliği açısından da önemlidir. -

A Descriptive Study of Social and Economic Conditions

55 LIFE IN NAKHICHEVAN AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC: A descriptive study of social and economic conditions Supported by UNDP/ILO Ayse Kudat Senem Kudat Baris Sivri Social Assessment, LLC July 15, 2002 55 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary and Next Steps Preface Characteristics of the Region History Governance Demographics Household Demographics and Employment Conditions Employment/ Unemployment Education Economic Assessment Government Expenditures NAR’s Economic Statistics Household Expenditure Structure Income Structure Housing Conditions Determinants of Welfare Agriculture Sector in NAR Water Electricity Financing Feed for Livestock Magnitude of Land Holding Subsidies Markets NAR Region District By District Infrastructure Sector Energy Power Generation Natural Gas Project Water Supply Transportation Social Infrastructure 56 57 Health Education Enterprise Sector People’s Priorities Issues Relating to Income Generation Trust and Vision Money and Banking Community Development ARRA Damage Assessment for the Region Other Donor Activities 57 58 Summary and Next Steps The 354,000 people who live in the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic (NAR) present a unique development challenge for the Government of Azerbaijan and for the international community. Cut off and blockaded from the rest of Azerbaijan as a result of the conflict with Armenia, their traditional economic structure and markets destroyed by the collapse of the former Soviet Union, their physical and social infrastructure hampered by a decade or more of lack of maintenance and rehabilitation funding, NAR’s present status is worse than much of the rest of the country and its prospects for the future require imagination and innovative thinking. This report deals with the challenges of NAR today and what peoples’ priorities are for the future. -

Turgut Özal Twenty Years After: the Man and the Politician

COMMENTARY TURGUT ÖZAL TWENTY YEARS AFTER: THE MAN AND THE POLITICIAN Turgut Özal Twenty Years After: The Man and the Politician CENGİZ ÇANDAR* ABSTRACT Whether Turgut Özal was a good politician remains up for debate. However, there is no question that he indeed was (and is) a significant historical persona. He guided his country into the twenty-first century. When Özal suddenly passed away in 1993, he had already led Turkey to the next century, even though the twenty-first century would technically begin only seven years later. mong the numerous com- political skills. In particular, he held mentaries published following in high regard Sultan Abdulhamid II, ATurgut Özal’s death, it was the an Ottoman sultan of the last period following remark that struck me the of the Empire of equally high caliber. hardest: “Turgut Bey was not a good I remember his expressed admiration politician. For he was a good man.” for Mehmed the Conqueror, Selim I, Suleiman the Magnificient, Murad II This was the most striking assessment and Bayezid II, whom he would refer to me because it was his qualities as a to with a facial expression overshad- good man that marked me in our fre- owed by a sense of inadequacy and quent encounters over the final two modesty: “What kind of men were years of his life. Turgut Özal was an they? How did they rule over such extremely courageous man, who did vast lands and such a diverse popu- not seem to posess the supposedly lation? Look at us, and look at them!” * Journalist, indispensable qualities of any good and a former adviser to politician: ruthlessness and the killing The people he talked about were rul- President instinct. -

Turkey-Azerbaijan Energy Relations: a Political and Economic Analysis

International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy Vol. 5, No. 1, 2015, pp.27-44 ISSN: 2146-4553 www.econjournals.com Turkey-Azerbaijan Energy Relations: A Political and Economic Analysis Cagla Gul YESEVI Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Turkey. Email: [email protected] Burcu Yavuz TIFTIKCIGIL Faculty of Economics, Administrative and Social Sciences, Gedik University, Istanbul, Turkey. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: It is now widely recognized that Turkey-Azerbaijan relations have always been strong and described with the phrase "one nation with two states”. This paper is concerned with economic and political nature of Turkey-Azerbaijan relations. Initially, the evolution of Turkish- Azerbaijani relations after the independence of Azerbaijan has been examined. This paper gives an overview of the impacts of Nagorno-Karabagh issue and efforts to normalize the relations between Turkey and Armenia on relations between Turkey and Azerbaijan. Energy has a special place in the relationship between the two countries. Azerbaijan’s economy, energy sectors of Azerbaijan and Turkey has been assessed. Moreover, this paper gives a comparative analysis on economic relationship between Turkey and Azerbaijan. This study finally discusses the main trends and contributions of energy projects on Turkey-Azerbaijan relations. Keywords: Turkey; Azerbaijan; Politics; Economy; Energy JEL Classifications: O57; Q41; Q43; Q48 1. Introduction Turkey has distanced itself from the Turkic people of Soviet Union, with whom it has ethnic and language affiliations, since its establishment. The primary aim was determined as the prevention of the spread of communism within the country and Turanist movements were not supported. -

The South Caucasus: Where the Us and Turkey Succeeded Together

THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: WHERE THE US AND TURKEY SUCCEEDED TOGETHER As Americans and Turks discuss the ups and downs in their relationship, the strategically important South Caucasus is one area, where, working together, Turkey and the United States have helped bring about historic changes. More can be done to realize the region’s promise should the US and Turkey deepen their partnership with Azerbaijan and Georgia and build on the policies that have proven to be successful. This success has been based on forward-looking pragmatism and recognition of common interests. Acknowledging the achievements in the South Caucasus and learning from them can contribute to future progress in the US-Turkey relationship. Elin Suleymanov∗ ∗ Elin Suleymanov is Senior Counselor with the Government of Azerbaijan. The views and opinions are his own and do not imply an endorsement by the employer. ormerly a Soviet backyard, the South Caucasus is increasingly emerging as a vital part of the extended European space. Sandwiched between the Black and the Caspian seas, the Caucasus F also stands as a key juncture of Eurasia. Living up to its historic reputation, the South Caucasus, especially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is now literally at the crossroads of the East-West and North – South transport corridors. Additionally, the Caucasus has been included concurrently into a rather vague “European Neighborhood” and an even vaguer “Greater Middle East.” This represents both the world’s growing realization of the region’s importance and the lack of a clear immediate plan to address the rising significance of the Caucasus. Not that the Caucasus has lacked visionaries. -

Full-Text of General Report

CPT/Inf (2007) 39 European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) 17th General Report on the CPT's activities covering the period 1 August 2006 to 31 July 2007 Strasbourg, 14 September 2007 The CPT is required to draw up every year a general report on its activities, which is published. This 17th General Report, as well as previous general reports and other information about the work of the CPT, may be obtained from the Committee's Secretariat or from its website: Secretariat of the CPT Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex, France Tel: +33 (0)3 88 41 20 00 Fax: +33 (0)3 88 41 27 72 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.cpt.coe.int CPT: 17TH GENERAL REPORT 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE................................................................................................................................................................ 5 ACTIVITIES DURING THE PERIOD 1 AUGUST 2006 TO 31 JULY 2007 ............................................... 6 Visits ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Meetings and working methods .............................................................................................................. 9 Publications........................................................................................................................................... 10 ORGANISATIONAL MATTERS .................................................................................................................... -

Genocide and Deportation of Azerbaijanis

GENOCIDE AND DEPORTATION OF AZERBAIJANIS C O N T E N T S General information........................................................................................................................... 3 Resettlement of Armenians to Azerbaijani lands and its grave consequences ................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Iran ........................................................................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Turkey ................................................................................... 8 Massacre and deportation of Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the 20th century .......................... 10 The massacres of 1905-1906. ..................................................................................................... 10 General information ................................................................................................................... 10 Genocide of Moslem Turks through 1905-1906 in Karabagh ...................................................... 13 Genocide of 1918-1920 ............................................................................................................... 15 Genocide over Azerbaijani nation in March of 1918 ................................................................... 15 Massacres in Baku. March 1918................................................................................................. 20 Massacres in Erivan Province (1918-1920) ............................................................................... -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „ACHIEVING SECURITY AND STABILITY IN THE REGION OF SOUTH CAUCASUS: WHAT ROLE FOR INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS? Study on the role and effectiveness of the UN, the OSCE, the CIS and the EU in facilitation of the conflict resolution in South Caucasus“ Verfasserin Mag. Esmira Jafarova angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. A-092 300 Studienblatt: Dissertationsgebiet lt. Dr.-Studium der Philosophie UniStG Studienblatt: Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Otmar Höll, tit. Ao. Univ.-Prof. CONTENTS Acknowledgement and dedication 5 INTRODUCTION 6 Chapter I: SOUTH CAUCASUS IN A PERSPECTIVE 12 1. South Caucasus republics after independence: challenges of transition 12 1.1. Democracy, human rights 14 1.2. Elections 18 1.3. Security sector 20 1.4. Economic challenges 21 2. Interests of key players in South Caucasus 28 2.1. Russia 29 2.2. United States 33 2.3. Turkey 36 2.4. Iran 38 2.5. Actors’ interactions 39 3. Summing up 42 Chapter II: SECURITY IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: Long-standing conflicts in the South Caucasus – “landmines” with delayed action 44 1. Conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh region 44 1.1. Roots of the conflict 45 1.2. Contemporary stage of the conflict 49 2. Conflicts within Georgia 52 2.1. Abkhazia 52 2.2. South Ossetia 56 2.3. Russian role in Georgian conflicts and August 2008 war 60 3. Summing up 66 Chapter III: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 67 1. Regime theory framework 67 1.1. Actors’ interests (concerned powerful actors) 73 1.2. Problem solving capacity 74 1.3. -

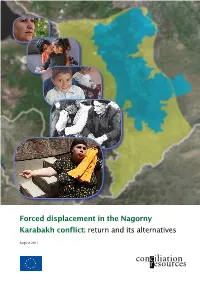

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives