Wrestling with Ssireum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans Wurm’S Ringbuch C

Hans Wurm’s Ringbuch c. 1507 - A Translation and Commentary By Keith P. Myers Exclusively for the ARMA, March 2002 The manuscript you see here is thought to have originated in approximately 1500 in the workshop of the Landshut woodcutter and printer Hans Wurm. “Landshut” could be translated as “grounds keeper”, which may go along with the description of Wurm as a “woodcutter” as well as a printer. Dr. Sydney Anglo, senior ARMA advisor and leading scholar of historical fencing, describes Wurm’s work as an “experimental and rudimentary block book”, and notes that it may have been one of the earliest printed treatises produced. The author remains anonymous, and only one copy is known to survive. It is thought to consist of the actual colored test prints made from the original wood blocks. It is unclear whether the Ringbuch was ever actually widely published. It was, however, plagiarized on at least two occasions. These later reproductions referred to the manuscript as “Das Landshuter Ringerbuch.” Although they demonstrate some dialect differences, these copies almost directly correlate with Wurm’s Ringbuch. Both likely arose independently of each other, and where based directly upon Wurm’s earlier work. The first copy is dated to approximately 1507. It does not designate the exact year, the author, the printer, or the locale. While it places the techniques in the same order as Wurm, the grapplers in the illustrations are dressed in a completely different fashion than in Wurm’s Ringbuch. The second copy is dated to approximately 1510. It originated from the Augsberg printer Hannsen Sittich. -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Vice President U Myint Swe: Government Succeeds in Reopening Kyin San Kyawt Gate

INFRASTRUCTURE IS KEY TO EQUITABLE DEVELOPMENT PAGE-8 (OPINION) The Global New Light of Myanmar NEXT GENERATION PLATFORM 13 JANUARY 2019 THE GLOBAL NEW LIGHT OF MYANMAR NATIONAL Meeting to form Workers Coordinating Committee (WCC) held in Hlinethaya Tsp By Thu Naung Kyaw (Hledan) Dip. in English (YUFL) WELL-KNOWN modern teashop in Hledan makes a bowl of oil noodles in the way that the steaming hot noodles are sieved into a plastic water bowl with handle, commonly used in bath- A rooms, in which the concoction is done, afterwards being put PAGE-6 Pull-out supplementinto a porcelain plate and, finally, served. Moreover, Hledan has another popular teashop, only two branches of which are running there in the town. There, when a glass of cold drink is ordered, they use a generous amount of unevenly hewn ice cubes, rather than using purified ice cubes. Also, the bottles of soybean with their rusty metal caps staining their mouths are not worth ordering. Next, a roadside Monhingha shop, which, however, was known to be in the list of pioneers of the town, asked us to hold our horses as the broth had ran out. A moment later, a trishaw came with many plastic bags, each holding Monhingha broth – boiling hot – all of which was eventually poured down into the large bowl. In the Hledan market, a wholesaling shop that sells fried vermicelli and fried noodles adds the entire packet of Ajinomoto, the seasoning powder, into a giant frying pan. Those noodles and vermicelli are sold to the other shops retailing various salads, pork on stick, and so on. -

History of Tae Kwon Do.Pdf

Tae Kwon Do History Introduction: Although modern Taekwondo has actually only existed for about 50 years (the martial art known Tae Kwon Do was developed between 1945 and 1955 and only became known as Tae Kwon Do in 1955.), it is based upon Shotokan Karate, another 20th century martial art, and ancient Korea martial arts, such as Taekkyon and Subak, that have lost favor in modern times. Tae Kwon Do is a martial art that means "The Way of the Feet and Hands". Writings on Taekwondo history usually portray Taekwondo as an unique product of Korean culture, developed over the long course of Korean history since the Three Kingdoms Era. However, Taekwondo's primary influence came from Japanese Karate that was introduced into Korea during the Japanese occupation of Korea during the early 1900s. Few written records on ancient Korean history exist, so factual information on Korean martial arts is scarce and sketchy. Because of this, most Korean martial arts writers find something in Korean history to support their claims; writers on Tae Kwon Do included. If one researches the history of Tae Kwon Do, in the research they will find differing and sometimes contradictory information. Majority of this information is a summary taken from Reference 1. For more details, please review the entire material on history of Tae Kwon Do from Reference 1. Origins of Tae Kwon Do: Empty-hand fighting did not originate wholly in only one country, but it developed naturally in every place humans settled. In each country, people adapted their fighting techniques to deal with the dangers in their local environments. -

AIS Framework for Rebooting Sport

Appendix B — Minimum baseline of standards for Level A, B, C activities for high performance/professional sport 1 THE AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF SPORT (AIS) FRAMEWORK FOR REBOOTING SPORT IN A COVID-19 ENVIRONMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY May 2020 The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) Framework for Rebooting Sport in a COVID-19 Environment — Executive Summary 2 INTRODUCTION Sport makes an important contribution to the physical, psychological and emotional well-being of Australians. The economic contribution of sport is equivalent to 2–3% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating effects on communities globally, leading to significant restrictions on all sectors of society, including sport. Resumption of sport can significantly contribute to the re-establishment of normality in Australian society. The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS), in consultation with sport partners (National Institute Network (NIN) Directors, NIN Chief Medical Officers (CMOs), National Sporting Organisation (NSO) Presidents, NSO Performance Directors and NSO CMOs), has developed a framework to inform the resumption of sport. National Principles for Resumption of Sport were used as a guide in the development of ‘the AIS Framework for Rebooting Sport in a COVID-19 Environment’ (the AIS Framework); and based on current best evidence, and guidelines from the Australian Federal Government, extrapolated into the sporting context by specialists in sport and exercise medicine, infectious diseases and public health. The principles outlined in this document apply equally to high performance/professional level, community competitive and individual passive (non-contact) sport. The AIS Framework is a timely tool for ‘how’ reintroduction of sport activity will occur in a cautious and methodical manner, to optimise athlete and community safety. -

A Sociocultural Analysis of Korean Sport for International Development Initiatives

A Sociocultural Analysis of Korean Sport for International Development Initiatives Dongkyu Na Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Kinetics School of Human Kinetics Faculty of Health Sciences University of Ottawa © Dongkyu Na, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Korean Sport for International Development ii Abstract This dissertation focuses on the following questions: 1) What is the structure of the Korean sport for international development discourse? 2) How are the historical transformations of particular rules of formation manifested in the discourse of Korean sport for international development? 3) What knowledge, ideas, and strategies make up Korean sport for international development? And 4) what are the ways in which these components interact with the institutional aspirations of the Korean government, directed by the official development assistance goals, the foreign policy and diplomatic agenda, and domestic politics? To address these research questions, I focus my analysis on the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) and its 30 years of expertise in designing and implementing sport and physical activity–related programs and aid projects. For this research project, I collected eight different sets of KOICA documents published from 1991 to 2017 as primary sources and two different sets of supplementary documents including government policy documents and newspaper articles. By using Foucault’s archaeology and genealogy as methodological -

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Fall 2016 Women, Real and Imagined, in Asian Art Sponsored by the Society for Asian Art

Arts of Asia Lecture Series Fall 2016 Women, Real and Imagined, In Asian Art Sponsored by The Society for Asian Art Queen Seondeok (r. 632 - 647) of Silla: Korea’s First Queen Kumja Paik Kim, March 10, 2017 Study Guide Queen Seondeok 선덕여왕 善德女王 (r. 632-647) Queen Seondeok’s given name Deokman 덕만 德曼; born in Gyeongju 경주 慶州 King Jinpyeong 진평왕 眞平王 (r. 579-632) and Lady Maya 마야보인 摩耶夫人 Monuments built with Queen Seondeok’s Support: 1. Cheomseong-dae 첨성대 瞻星臺 (star observing platform or star gazing tower) 2. Bunhwang-sa 분황사 芬皇寺, Gyeongju – Venerable Jajang 자장 慈藏 (590–658) 3. Nine-story pagoda구층탑 九層塔, 645 at Hwangyong-sa 황용사 皇龍寺, 553-569, Gyeongju, architect: Abiji 아비지 阿非知 – Venerable Jajang 4. Tongdo-sa 통도사 通度寺, 646, Yangsan near Busan – Veneralble Jajang Samguk Sagi 삼국사기 三國史記 (History of the Three Kingdoms) by Kim Bu-sik 김부식 金富軾 (1075-1151), 1145 Samguk Yusa 삼국유사 三國遺史(Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms) by monk Iryeon 일연一然 (1206-1289), 1285 Queen Seondeok’s three predictions = Jigi Samsa 지기삼사 知幾三事 Two other Silla Queens = Jindeok 진덕여왕 眞德女王 (r. 647-654) and Jinseong 진성여왕 眞聖女王 (r. 887-897) Silla’s Ruling Clans: Pak 박 朴; Seok 석 昔; and Kim 김 金 Bak (Pak) Hyeokkeose 박혁거세 朴赫居世 (r. 69 BCE – 4 CE) Seok Talhae 석탈해 昔脫解 (r. 57 – 80) 鵲 – 鳥 = 昔 (Seok) Kim Alji 김알지 金閼智 (67 - ?) Michu 미추 味鄒 (r. 262-284), the first Silla ruler from the Kim clan Queen Seondeok’s Sisters: Princess Seonhwa and Princess Cheonmyeong (King Muyeol’s mother) Silla’s Bone-rank (golpum 골품 骨品) system: 1) sacred-bone (seonggol 성골聖骨) 2) true-bone (jingol 진골 眞骨) 3) head-rank (dupum 두품 頭品) The Great Tomb of Hwangnam, Northern Mound: Hwangnam Daechong Bukbun 황남대총북분 皇南大塚北墳 Tomb of the Auspicious Phoenix: Seobong-chong 서봉총 瑞鳳塚 Seoseo 서서 瑞西 (瑞); Bonghwang 봉황 鳳凰 (鳳); chong 총 塚 Maripgan 마립간 麻立干: Naemul (356-402); Silseong (402-417): Nulji (417-458); Jabi (458-479); Soji (479-500) Wang 왕 王: From King Jijeung (r. -

Ju-Jitsu Technical Handbook

Ju-Jitsu Technical Handbook 2019 Chungju World Martial Arts Masterships Organizing Committee Ⅰ. Introduction 1. Preface ···································································································· 3 2. Organization Bodies(WMC, 2019 Chungju WMOC) ·················· 4 Ⅱ. General Information 1. 2019 Chungju World Martial Arts Masterships in Brief ·········· 6 2. Accreditation and Validation ····························································· 7 3. Immigration and Visa ········································································ 8 4. Transportation ····················································································· 8 5. Accommodation ················································································· 9 6. Media ···································································································· 9 7. Medical Service ··················································································· 9 8. Host Country/City Information ··················································· 10 Ⅲ. Technical Information 1. Competition Date ············································································ 13 2. Venue ·································································································· 13 3. Competition Management ···························································· 13 4. Competition Events ········································································ 13 5. Competition Schedule ···································································· -

State of Play: 2017 Report by the Aspen Institute’S Project Play Our Response to Nina and Millions of Kids

STATE OF PLAY 2017 TRENDS AND DEVELOPMENTS 2017 THE FRAMEWORK SPORT as defined by Project Play THE VISION Sport for All, Play for Life: An America in which A Playbook to Get Every All forms of physical all children have the Kid in the Game activity which, through organized opportunity to be by the Aspen Institute or casual play, aim to active through sports Project Play express or improve youthreport.projectplay.us physical fitness and mental well-being. Participants may be motivated by intrinsic or external rewards, and competition may be with others or themselves (personal challenge). ALSO WORTH READING Our State of Play reports on cities and regions where we’re working. Find them at www.ProjectPlay.us ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 SCOREBOARD 3 THE 8 PLAYS 7 CALL FOR LEADERSHIP 16 NEXT 18 ENDNOTES 20 INTRODUCTION Nina Locklear is a never-bashful 11-year-old from Baltimore with common sense well beyond her years. She plays basketball, serves as a junior coach at her school to motivate other kids, and doesn’t hesitate to tell adults why sports are so valuable. “It’s fun when you meet other people that you don’t know,” Nina told 400 sport, health, policy, industry and media leaders at the 2017 Project Play Summit. “I’m seeing all of you right now. I don’t know any of you, none of you. But now that I see you I’m like, ‘You’re family.’ It (doesn’t) matter where you live, what you look like, y’all my family and I’m gonna remember that.” If you’re reading this, you’re probably as passionate as Nina about the power of sports to change lives. -

NCKS News Fall 2014.Pdf

N A M C E N T E R FOR K O R E A N S T U D I E S University of Michigan 2014-2015 Newsletter Hallyu 2.0 volume Contemporary Korea: Perspectives on Minhwa at Michigan Exchange Conference Undergraduate Korean Studies INSIDE: 2 3 From the Director Korean Studies Dear Friends of the Nam Center: Undergraduate he notion of opportunity underlies the Nam Center’s programming. Studies Scholars (NEKST) will be held on May 8-9 of 2015. In its third year, TWhen brainstorming ideas, setting goals for an academic or cultural the 2015 NEKST conference will be a forum for scholarly exchange and net- Exchange program, and putting in place specific plans, it is perhaps the ultimate grati- working among Korean Studies graduate students. On May 21st of 2015, the fication that we expect what we do at the Nam Center to provide an op- Nam Center and its partner institutions in Asia will host the New Media and Conference portunity for new experiences, rewarding challenges, and exciting directions Citizenship in Asia conference, which will be the fourth of the conference that would otherwise not be possible. Peggy Burns, LSA Assistant Dean for series. The Nam Center’s regular colloquium lecture series this year features he Korean Studies Undergraduate Exchange Conference organized Advancement, has absolutely been a great partner in all we do at the Nam eminent scholars from diverse disciplines. jointly by the Nam Center and the Korean Studies Institute at the Center. The productive partnership with Peggy over the years has helped This year’s Nam Center Undergraduate Fellows program has signifi- T University of Southern California (USC) gives students who are interested open many doors for new opportunities. -

K O R E a N C in E M a 2 0

KOREAN CINEMA 2006 www.kofic.or.kr/english Korean Cinema 2006 Contents FOREWORD 04 KOREAN FILMS IN 2006 AND 2007 05 Acknowledgements KOREAN FILM COUNCIL 12 PUBLISHER FEATURE FILMS AN Cheong-sook Fiction 22 Chairperson Korean Film Council Documentary 294 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 130-010 Animation 336 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Daniel D. H. PARK Director of International Promotion SHORT FILMS Fiction 344 EDITORS Documentary 431 JUNG Hyun-chang, YANG You-jeong Animation 436 COLLABORATORS Darcy Paquet, Earl Jackson, KANG Byung-woon FILMS IN PRODUCTION CONTRIBUTING WRITER Fiction 470 LEE Jong-do Film image, stills and part of film information are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, and Film Festivals in Korea including JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), PIFF APPENDIX (Pusan International Film Festival), SIFF (Seoul Independent Film Festival), Women’s Film Festival Statistics 494 in Seoul, Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival, Seoul International Youth Film Festival, Index of 2006 films 502 Asiana International Short Film Festival, and Experimental Film and Video Festival in Seoul. KOFIC appreciates their help and cooperation. Contacts 517 © Korean Film Council 2006 Foreword For the Korean film industry, the year 2006 began with LEE Joon-ik's <King and the Clown> - The Korean Film Council is striving to secure the continuous growth of Korean cinema and to released at the end of 2005 - and expanded with BONG Joon-ho's <The Host> in July. First, <King provide steadfast support to Korean filmmakers. This year, new projects of note include new and the Clown> broke the all-time box office record set by <Taegukgi> in 2004, attracting a record international support programs such as the ‘Filmmakers Development Lab’ and the ‘Business R&D breaking 12 million viewers at the box office over a three month run. -

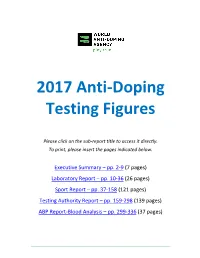

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples).