Plaintiffs (Respondents)) V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BCBUA Areas - 2019

BCBUA Areas - 2019 AREA 1: Vancouver Island South Towns included: Brentwood Bay; Chemainus; Cobble Hill; Crofton; Duncan; Esquimalt; Ladysmith; Lake Cowichan; Langford; Metchosin; Saanichton; Salt Spring Island; Shawnigan Lake; Sidney; Victoria; AREA DIRECTOR: Scott Eckardt, [email protected] AREA 2: Vancouver Island North Towns included: Black Creek; Bowser; Campbell River; Comox; Courtenay; Cumberland; Lantzville;Lazo; Merville; Nanaimo; Nanoose Bay; Parksville; Port Alberni; Qualicum Beach; Royston AREA DIRECTOR: Brad Jones, [email protected] AREA 3: Lower Mainland East Towns included: Abbotsford; Agassiz; Aldergrove; Anmore; Chilliwack; Coquitlam; Maple Ridge; Mission; Pitt Meadows; Port Coquitlam; Port Moody; Rosedale; Sardis; AREA DIRECTOR: Gary Webber, [email protected] AREA 4: Lower Mainland West Towns included: Burnaby; Gibsons; Halfmoon Bay; New Westminster; North Vancouver; Powell River; Richmond; Roberts Creek; Sechelt; Squamish; Vancouver; West Vancouver; AREA DIRECTOR: Michael Yamaguchi, [email protected] AREA 5: Lower Mainland South Towns included: Cloverdale; Delta; Ladner; Langley; Surrey; Tsawwassen; White Rock; AREA DIRECTOR: Brad Woof, [email protected] AREA 6: Thompson Okanagan Towns included: Canoe; Celista; Chase; Kamloops; Merritt; Revelstoke; Salmon Arm; Sicamous; Sorrento; AREA DIRECTOR: Mark Wright, [email protected] AREA 7: South Okanagan Towns included: Coldstream; Enderby; Kaleden; Kelowna; Lumby; Oliver; Peachland; Penticton; Rutland; Summerland; Vernon; Westbank; AREA DIRECTOR: Darcy Rysz, [email protected] AREA 8: Kootenays Towns included: Castlegar; Cranbrook; Creston; Fernie; Fruitvale Golden; Grand Forks; Greenwood; Invermere; Kaslo; Montrose; Nelson; Parsons; Slocan Park; South Slocan; Trail; AREA DIRECTOR: Bill MacMillan, [email protected] AREA 9: Northern B.C. Towns included: Burns Lake; Dawson Creek;Fort St. James; Fort Nelson; Fort St. John; Houston; Kitimat; Prince George; Prince Rupert; McBride; Smithers; Quesnel; Terrace; Vanderhoof; Williams Lake; AREA DIRECTOR: Matt Lowndes, [email protected] . -

BACKGROUNDER 2006TSA0033-000979 Ministry of Tourism, Sport and the Arts July 22, 2006

BACKGROUNDER 2006TSA0033-000979 Ministry of Tourism, Sport and the Arts July 22, 2006 ABORIGINAL TEAM B.C. BRINGS HOME 102 MEDALS Athletes who won medals for Aboriginal Team B.C. NAME MUNICIPALITY SPORT GOLD SILVER BRONZE Artie Andrew Agassiz Soccer 1 Toni-Dawn Carter Agassiz Soccer 1 Cameron Garner Agassiz Soccer 1 Kimberly House Agassiz Soccer 1 Keith Jimmie Agassiz Soccer 1 Fran Kelly-Phillips Agassiz Soccer 1 Jennifer Leon Agassiz Soccer 1 Stephanie Leon Agassiz Soccer 1 Brenon McIntyre Agassiz Soccer 1 Demi Moore Agassiz Soccer 1 Beckey Pettis Agassiz Soccer 1 Matthew Point Agassiz Soccer 1 Dale Quipp Agassiz Soccer 1 Frank Quipp Agassiz Soccer 1 Richard Dobson Alert Bay Soccer 1 Frisco Billyboy Alexis Creek Wrestling 1 Rubina Haines Alexis Creek Wrestling 1 Shari Harry Alexis Creek Wrestling 1 Jeremy Sterling Barrier Softball 1 Zack Wilson Barrier Softball 1 Riggs Young Barrier Softball 1 Trey Young Barrier Softball 1 Jolene Eustache Barrier Swimming 4 4 1 Steven Meacham Bella Coola Track and Field 1 2 Gordon Elliot Bentwood Bay Soccer 1 Tyler Andrew Boston Bar Softball 1 Alan Campbell Boston Bar Softball 1 Katia Olsen Brentwood Bay Soccer 1 Nick Olsen Brentwood Bay Soccer 1 Shane Paul-Tom Brentwood Bay Soccer 1 - 2 - Keith Sam Brentwood Bay Soccer 1 Connor Clifton Burnaby Wrestling 1 Markell Henderson Campbell River Soccer 1 Melissa Christopher Canim Lake Soccer 1 Christine Dixon Canim Lake Soccer 1 Marcia Dixon Canim Lake Soccer 1 Angel Theodore Canim Lake Soccer 1 Azarius Garcia Central Saanich Lacrosse 1 Andrew Henri Chilliwack -

Gateway Tech Park 2261 Keating Cross Road VICTORIA | BC

Gateway Tech Park 2261 Keating Cross Road VICTORIA | BC FIRST CLASS SUBURBAN OFFICE Tristan Spark Ty Whittaker Vice President Personal Real Estate Corporation 250 414 8391 Executive Vice President [email protected] 250 414 8395 [email protected] Gateway Tech Park is Victoria’s largest and most successful business park, only a 20-minute drive from Downtown Victoria and a 10-minute drive to Victoria International Airport and BC Ferries terminal. An integral part of the Keating Cross Business District, Gateway Tech Park will be the most sought after office opportunity in the district offering up to 31,000 SF of the total 180,575 SF office space. Designed with the tech industry in mind, Gateway Teck Park is an unbeatable offering in a highly accessible sought after area. PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS | Three sources of fiber connectivity Modern concrete and glass construction Back-up generator for entire facility Existing improvements in place Large open floor plates End of trip bicycle storage available Secure free on-site parking, 1 stall per 312 SF leased On-site Landlord manager Separate professional entrance available for each unit Impeccably maintained OFFICE FEATURES | Furniture Kitchen Facilities Meeting Room Modern 582 On-site Anytime Fitness Building Design Parking Stalls Located on Site AVAILABLE AREAS | RENTAL RATES | Main 8,575 SF Rates Contact agents for rental rates Main 7,333 SF Lower Main 12,000 SF Additional Rent $6.29 PSF per annum (est. 2019), excluding utilities Main (former Cafe) 3,630 SF Improvement The landlord will provide a tenant improvement allowance for Total Available 31,538 SF Allowance leases with a term of five (5) years or greater for shell space. -

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District by Sylvia Kenny University of Victoria, School of Earth & Ocean Sciences Co-op British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection Prepared for the Capital Regional District, Victoria, B.C. December 2004 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kenny, Sylvia. Aquifers of the Capital Regional District. Cover title. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-52651 1. Aquifers - British Columbia - Capital. 2. Groundwater - British Columbia - Capital. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. II. University of Victoria (B.C.). School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. III. Capital (B.C.) IV. Title. TD227.B7K46 2004 333.91’04’0971128 C2004-960175-X Executive summary This project focussed on the delineation and classification of developed aquifers within the Capital Regional District of British Columbia (CRD). The goal was to identify and map water-bearing unconsolidated and bedrock aquifers in the region, and to classify the mapped aquifers according to the methodology outlined in the B.C. Aquifer Classification System (Kreye and Wei, 1994). The project began in summer 2003 with the mapping and classification of aquifers in Sooke, and on the Saanich Peninsula. Aquifers in the remaining portion of the CRD including Victoria, Oak Bay, Esquimalt, View Royal, District of Highlands, the Western Communities, Metchosin and Port Renfrew were mapped and classified in summer 2004. The presence of unconsolidated deposits within the CRD is attributed to glacial activity within the region over the last 20,000 years. Glacial and glaciofluvial modification of the landscape has resulted in the presence of significant water bearing deposits, formed from the sands and gravels of Capilano Sediments, Quadra and Cowichan Head Formations. -

Peoyincial Museum

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA EEPOET OP THE PEOYINCIAL MUSEUM OP . NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY FOR THE YEAR 1941 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OP THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C. : Printed by CHABLES P. BANFIELD, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1942. To His Honour W. C. WOODWARD, Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUE HONOUR: The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology for the year 1941. GEORGE S. PEARSON, Provincial Secretary. Provincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.C. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OP NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY, VICTORIA, B.C., December 31st, 1941. The Honourable George S. Pearson, Provincial Secretary, Victoria, B.C. SIR,—The undersigned respectfully submits herewith a report of the activities of the Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology for the year 1941. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, G. CLIFFORD CARL, Acting Director. DEPARTMENT of the PROVINCIAL SECRETARY. • The Honourable GEORGE S. PEARSON, Minister. P. WALKER, Deputy Minister. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY. Staff: G. CLIFFORD CARL, Ph.D., Acting Director. WINIFRED V. HARDY, Botanist (to April 30). GEORGE A. HARDY, Botanist (from May 1). MARGARET CRUMMY, B.A., Stenographer. LILLIAN C. SWEENEY, Assistant Preparator. E. A. COOKE, Laboratory Assistant and Attendant. H. H. PEGLER, Attendant. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY. OBJECTS. (a.) To secure and preserve specimens illustrating the natural history of the Province. (6.) To collect anthropological material relating to the aboriginal races of the Province. (c.) To obtain information respecting the natural sciences, relating particularly to the natural history of the Province, and to increase and diffuse knowledge regarding the same. -

Peovincial Museum

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA REPORT OF THE PEOVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY FOR THE YEATS 1931 PRINTED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. VICTORIA, B.C.: Printed by CHAHLES F. BANFIELO, Printer to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1932. To His Honour J. W. FOEDHAM JOHNSON, Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR : The undersigned respectfully submits herewith the Annual Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History for the year 1931. SAMUEL LYNESS HOWE, Provincial Secretary. Provincial Secretary's Office, Victoria, B.C., March 23rd, 1932. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, VICTORIA, B.C., March 23rd, 1932. The Honourable S. L. Howe, Provincial Secretary, Victoria, B.C. SIR,—I have the honour, as Director of the Provincial Museum of Natural History, to lay before you the Report for the year ended December 31st, 1931, covering the activities of the Museum. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant. FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. DEPARTMENT of the PROVINCIAL SECRETARY. The Honourable S. L. HOWE, Minister. P. DE NOE WALKER, Deputy Minister. PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY. Staff: FRANCIS KERMODE, Director. WILLIAM A. NEWCOMBE, Assistant Biologist. NANCY STARK, Recorder. JOHN F. CLARKE, Assistant Curator of Entomology. TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE. Object 5 Admission 5 Visitors 5 Activities 5 Anthropology and Archaeology 7, 11 Palaeontology 12 Botany 9, 12 Amphibia and Reptilia 6, 13 Ichthyology 9, 13 Entomology 10, 13 Marine Zoology 10, 13 Ornithology 10, 14 Oology 10, 14 Mammalogy : 10, 14 Publications received from other Museums 14 Accessions 11 REPORT of the PROVINCIAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY FOR THE YEAR 1931. -

Paleomagnetism and Counterclockwise Tectonic Rotation of the Upper Oligocene Sooke Formation, Southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia

499 Paleomagnetism and counterclockwise tectonic rotation of the Upper Oligocene Sooke Formation, southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia Donald R. Prothero, Elizabeth Draus, Thomas C. Cockburn, and Elizabeth A. Nesbitt Abstract: The age of the Sooke Formation on the southern coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, has long been controversial. Prior paleomagnetic studies have produced a puzzling counterclockwise tectonic rotation on the underlying Eocene volcanic basement rocks, and no conclusive results on the Sooke Formation itself. We took 21 samples in four sites in the fossiliferous portion of the Sooke Formation west of Sooke Bay from the mouth of Muir Creek to the mouth of Sandcut Creek. After both alternating field (AF) and thermal demagnetization, the Sooke Formation produces a single-component remanence, held largely in magnetite, which is entirely reversed and rotated counterclockwise by 358 ± 128. This is consistent with earlier results and shows that the rotation is real and not due to tectonic tilting, since the Sooke Formation in this region has almost no dip. This rotational signature is also consistent with counterclockwise rota- tions obtained from the northeast tip of the Olympic Peninsula in the Port Townsend volcanics and the Eocene–Oligocene sediments of the Quimper Peninsula. The reversed magnetozone of the Sooke sections sampled is best correlated with Chron C6Cr (24.1–24.8 Ma) or latest Oligocene in age, based on the most recent work on the Liracassis apta Zone mol- luscan fauna, and also a number of unique marine mammals found in the same reversed magnetozone in Washington and Oregon. Re´sume´ : L’aˆge de la Formation de Sooke sur la coˆte sud de l’ıˆle de Vancouver, Colombie-Britannique, Canada, a long- temps e´te´ controverse´. -

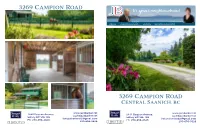

3269 Campion Road 1710 Albert Avenue in Neighbourhood

3269 Campion Road 1710 Albert Avenue In neighbourhood Jack Barker Lori Ann Sutherland sidney saanich peninsula victoria and island specialist 32691710 Campion Albert Av eRoadnue CentralVICT ORIA,Saanich, BC bc www.jackbarker.net www.jackbarker.net R2444E/M AX Beacon Camosun PAvenue,eninsula P roperties www.jackbarker.net 2444RE/M BeaconAX Camos uAvenue,n Peninsul a Properties www.jackbarker.net [email protected] [email protected] #Sidney 14 2510 BCBeva nV8L Ave n1X6ue E [email protected] Sidney# 14 25 BC10 B eV8Lvan A 1X6venue E [email protected] Sidney, British Columbia [email protected] [email protected] Sidney, British Columbia [email protected] [email protected] C A MOS U N CPh:ana d250-656-4626a, V8L 1W3 C A MOS U NPh:Ca n250-656-4626ada, V8L 1W3 P 250-655-0608 250-656-5626 P 250-655-060250-656-56268 3269 Campion Road 3269 Campion Road Campion Farm in Martindale Valley! Enjoy living on this sunny 6.48 acre equestrian property. This home was moved from the adjacent property in 2004. New foundation, services and totally updated, this warm country 2 level home offers 1840 sq. ft. of living space. Gracious living area on the main floor with cozy wood burning fireplace. Upstairs has 2 bedrooms and a large master with beautiful en-suite. The equestrian facilities are built to a high standard consisting of stalls for 3 horses, tack room, feed room, hydro, hot water and hay storage. Separate stall and paddock. The farm is fenced, crossed fenced, gated and includes an Olympic sized dressage riding ring! Enjoy the pastoral splendour of Central Saanich without sacrificing the modern amenities of the city. -

Canada Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences

DFO L bra y / MPO B bliotheque 11 111 11 111 ID 11 1 08001365 Annotated Bibliography of Nearshore Fish Habitat Maps for the Strait of Georgia J. Lessard, C.D. Levings, M.S. North, and D.J.H. Nishimura Department of Fisheries and Oceans of 11 te. ete apt is fieN end Science Branch '"'ek West Vancouver Laboratory 4160 Marine Drive OCT 1996 West Vancouver, British Columbia V7V 1N6 .44k414:64t.; . 1996 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences No. 2350 Fisheries Peches 1+1 and Oceans et Oceans Canada Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribu- tion is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 901-1425 were issued as Manuscript Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. -

WSANEC Emerging Land Or Emerging People Jack Horne

The Arbutus Review Vol. 3, No. 2 (2012) Horne WSANEC Emerging Land or Emerging People Jack Horne Abstract: The WSANEC Nation has been located on what is now known as the Saanich Peninsula on southern Vancouver Island since time immemorial. Remarkably little has been written about this Nation, which was divided by the Oregon Treaty in 1846 into Canadian/American sides of the border. In Canada the WSANEC Nation was then further divided into 4 separate reserves. This article examines the WSANEC Nation’s relationship with its traditional territories, the effects of colonization on this relationship, and ongoing resistance to continued colonization from both internal and external forces. WSANEC history is examined through the documentation in the Nation’s oral traditions, using the Douglas Treaties, the landmark Saanich Bay Marina Case, and James Island development as examples. Key Terms: WSANEC; Douglas Treaty; Coast Salish Introduction The WSANEC Nation is located on what is now known as the Saanich Peninsula on the southern part of Vancouver Island. WSANEC territories once encompassed the entire Saanich Peninsula, many of the surrounding Islands, and extended south onto the mainland of Washington State. With the signing of the Oregon treaty in 1846, WSANEC territories and people were divided into Canadian or American sides (Sage, 1946). As a result, family ties were disrupted and families on each side of the border were left to face different government policies. The WSANEC Nation in Canada is currently divided into four separate reserves located in the areas known today as: Tsawout, Tsartlip, Puaquachin, and Tseycum. While a great deal of scholarship has been written about the Indigenous peoples of British Columbia there has been remarkably little written about the WSANEC Nation. -

Down to Earth Gardens & Nursery 1096 Derrien Pl, Metchosin (250)

Down To Earth Gardens & Nursery Victoria Landscape & Gravel Ellice Recycling 1096 Derrien Pl, Metchosin 2516 Pleasant St. Victoria John St at Bridge St, Victoria (250) 391- 9366 (250) 381-2415 for leaf mulch For “Yard and Garden Mulch” downtoearthgardensandnursery.com (250) 386-8740 Nanaimo & Area Land Trust Numa Farms Nursery Growers Native Plant Nursery Swan Lake ~ Christmas Hill 3459 Luxton Rd, Metchosin 3145 Frost Rd, Cassidy Nature Sanctuary (250) 474-6005 (250) 816-6466 (near airport) (native plant sale every April) http://numafarmsnursery.com [email protected] www.nalt.bc.ca 3873 Swan Lake Rd, Victoria (250) 479-0211 Cannor Nursery Russell Nursery [email protected] 4660 Elk Lake Dr, Saanich 1370 Wain Rd, North Saanich www.swanlake.bc.ca (250) 656-0384 (250) 658-5415 Fraser’s Thimble Farms http://cannorvictoria.com/ [email protected] www.russellnursery.com 175 Arbutus Rd. Salt Spring Island GardenWorks Marigold Nurseries (250) 537-5788 1859 Island Highway, Colwood 7874 Lochside Dr Saanichton [email protected] (250) 478-2078 (250) 652-2342 www.thimblefarms.com 4290 Blenkinsop Rd, Saanich [email protected] (250) 721-2140 Dinter Nursery http://marigoldnurseries.com/ www.gardenworks.ca 2205 Phipps Rd (at Hwy 1), Duncan (250) 748-2023 Lochside Nursery Natural Resource Native Plant www.dinternursery.ca Dooley Rd at Lochside Dr Nursery Brentwood Bay 2466 Roome Road, Duncan BC Quamichan Native Plants (250) 544-3100 Tel: (250) 748-0684 2380 Hatchery Rd, Duncan http://www.lochside.ca/ Oud [email protected] (250) 597-0775 (call -

Vancouver Island Regional Districts and Municipalities

Vancouver Island Regional Districts and Municipalities Regional Districts and Municipalities each govern their own areas. Municipalities have a seat at the governance table of the neighbouring Regional District and are presented here to reflect which Regional District they partner with. REGIONAL DISTRICT OF MOUNT WADDINGTON Regional District of Mount Waddington Village of Port Alice Box 729 PO Box 130 2044 McNeill Road 1061 Marine Dr Port McNeill, BC, V0N 2R0 Port Alice, BC, V0N 2N0 Phone: (250) 956-3301 Phone: (250) 284-3391 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.rdmw.bc.ca/ Website: http://portalice.ca/ District of Port Hardy Village of Alert Bay 7360 Columbia St. 15 Maple Rd, Bag 2800 Box 68 Alert Bay, BC, V0N 1A0 Port Hardy, BC, V0N 2P0 Phone: (250) 974-5213 Phone: (250) 949-6665 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.alertbay.ca/ Website: http://www.porthardy.ca/ Town of Port McNeill Box 728 1775 Grenville Place Port McNeill, BC, V0N 2R0 Phone: (250) 956-3111 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.town.portmcneill.bc.ca/ 06/2015 1 Vancouver Island Regional Districts and Municipalities STRATHCONA REGIONAL DISTRICT Strathcona Regional District Village of Gold River 301-990 Cedar St PO Box 610 Campbell River, BC, V9W 7Z8 499 Muchalat Drive Phone: (250) 830-6700 Gold River, BC, V0P 1G0 Email: [email protected] Phone: (250) 283-2202 Website: http://www.strathconard.ca/ Email: [email protected] Website: http://home.cablerocket.com/~villageofgoldriver/