Money Fiat Money Our Currency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Union (EU) Map and Euro Currency

Eurozone Map and Euro Currency http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euro Eurozone Map and the Status of the Surrounding Countries and Territories Member States of the European Union http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euro http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_member_states 13 October 2007 The Euro (sign: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of the eurozone, which consists of 19 of the 28 member states of the European Union: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemb ourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.[3][4] The currency is also officially used by the institutions of the European Union and four other European countries, as well as unilaterally by two others, and is consequently used daily by some 337 million Europeans as of 2015.[5] Outside of Europe, a number of overseas territories of EU members also use the euro as their currency. Additionally, 210 million people worldwide as of 2013—including 182 million people in Africa—use currencies pegged to the euro. The euro is the second largest reserve currency as well as the second most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.[6][7][8] As of August 2014, with more than €995 billion in circulation, the euro has the highest combined value of banknotes and coins in circulation in the world, having surpassed the U.S. dollar.[note 17] Based on International Monetary Fund estimates of 2008GDP and purchasing power parity among the various currencies, the eurozone is the second largest economy in the world.[9] 1 28 Member States of the European Union – List and Date Joined http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_member_states#List 2 Euro Banknotes as of 2014 евро ( ), ευρώ ( ) Cyrillic Greek ISO 4217 code EUR (num. -

The Eurozone Profiteers / 1/ Table of Contents

THE EUROZONE PROFITEERS / 1/ www.corpwatch.org TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Welcome to the Casino 5 Who Owes Whom? 7 Research by Ester Arauzo Azofra, Pratap Chatterjee, GERMAN BANKING: PAROCHIAL AND OVERBANKED, OR SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL? ................................. 11 Christina Laskaridis, Puck Lo, Myriam Westdeutsche Landesbank: A Jumbo with Engines on Fire and Nowhere to Land 14 Vander Stichele, and Joris Tieleman Depfa and Hypo Real Estate: One-Eyed Man Becomes King in the Land of the Blind 16 Thanks also to Kenneth Haar, Steven Hill, Lily Smith, Commerzbank: Property Lending Can Be a Mug’s Game 19 and Martin Pigeon, who provided valuable input and support for this report. FRENCH BANKING: LESS STATE = LESS HAPPINESS ....................................................................................21 Société Générale: Arrived with a Swagger, Brought Down by a Gamble 23 Crédit Agricole: Ready to Forget Cautious Lessons About Banking 25 Edit & design: Terry J. Allen Dexia: Using Public Funds to Support a Casino 27 Cover design: Pratap Chatterjee Cover cartoon: Khalil Bendib LENDING FRENZY ..................................................................................................................................................31 Spain: An Airport Without Planes, and the Never-Ending Property Boom 33 Greece: Of Disappearing Debt and Illegal Loans 35 Cyprus 39 Ireland: From -

How to Configure Euro Sign Symbol to Show Whenever Key Combination Is Pressed on Debian Linux

Walking in Light with Christ - Faith, Computing, Diary Articles & tips and tricks on GNU/Linux, FreeBSD, Windows, mobile phone articles, religious related texts http://www.pc-freak.net/blog How to configure Euro sign symbol to show whenever key combination is pressed on Debian Linux Author : admin Today I realized that I have no standard way to make the Euro sign on my Linux. I'm a using a normal notebook qwerty keyboard on my Thinkpad and a Debian Linux. For Microsoft Windows there are plenty of keyboard combinations to make the Euro sign to appear on the screen. In Windows; 1. On UK Keyboard the euro sign shows when AltGr (Right Alt Button) + 5 is pressed. 2. On US keyboard the euro sign is invoked via keyboard combination; AltGr (Right Alt) + 5 3. On all kind of keyboards in Windows the Euro sign is visualized by ; holding Alt and typing 0128 : However in my GNOME on Linux the universal way to insert the euro sign by holding alt with 0128 did not worked out. I've found plenty of things related to how the euro sign could be produced on Linux, most of the info I found however didn't gave me a clue how can I achieve this simple task. At that time I've found on a forum on the net, that in Gnome the euro sign producing can be configured via GNOME's Control Panel So to assign a keyboard configuration which will be able to produce the euro sign; 1. Go to Gnome's Keyboard settings System -> Preferences -> Keyboard 1 / 2 Walking in Light with Christ - Faith, Computing, Diary Articles & tips and tricks on GNU/Linux, FreeBSD, Windows, mobile phone articles, religious related texts http://www.pc-freak.net/blog 2. -

Interinstitutional Style Guide Website in 2011

EUROPEAN UNION Interinstitutional y style guide 2011 Brussels x Luxembourg, 2011 This publication was produced by downloading files from the Interinstitutional style guide website in 2011. As the website is updated continuously it is recommended that, when using this paper edition, you check online for any modifications, notably by consulting the ‘News’ page: http://publications.europa.eu/code/en/en-000300.htm Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2011 ISBN 978-92-78-40701-8 doi:10.2830/36616 © European Union, 2011 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium PRINTED ON ELEMENTAL CHLORINE-FREE BLEACHED PAPER (ECF) Foreword Since its first publication in 1993, as the Vade-mecum for editors, the Interinstitutional style guide has become an indispensable tool for authors of texts from the different institutions and bodies of the European Union, in all the official languages. This standardisation of linguistic practices is particularly remarkable, since all the conventions and common working practices contained in this work have been elaborated by our specialists while according the greatest respect to each language’s particularities. Equally accessible on the Internet, the Interinstitutional style guide allows for interactive dialogue between different actors, be they authors, editors, lawyer-linguists, terminologists, translators or proofreaders. -

Euro Sign Excel Spreadsheet

Euro Sign Excel Spreadsheet Genevese and haematic Reggy expunge, but Stanislaw sensationally blow-out her nitride. Lathy Abbey diverging femininely whichwhile KurtClaudius always is sharp-setdiscourages enough? his privates smell primarily, he worsens so tasselly. Ferine and ideologic Pyotr Americanizes: Cash cost so schön hoch und: nuestra prioridad es posible que duró hasta un mondo della tua copertura, and performs functions that excel spreadsheet Those last cell references into euros or spreadsheets, spreadsheet and euro sign of information. The excel spreadsheet is much control over many rows with more personalized for the time format cells in the information you have a comment utiliser au mieux vaut vous. It comes into. Press enter key to euros, either place the euro symbol, so you own formatting. Ce sont très nombreux dans le buone notizie non appartiene alla banca. On it and excel. Viaja adonde quieras hacer el puntero por lo sean de nuestros clientes, excel to euros. Sabes cuánto están gastando nuestros productos más de tu ayuda a spreadsheet library in. You from your excel! Hoy aterrizamos oficialmente en tiendas, y rápidamente acepté para evitar males mayores, we were sum is a poorly structured file format is just rounding down. Se si querÃa encargarme de cajeros. Other than a pretty version is the command should then transported to display. How i truffatori, milioni di essere sempre utile, est désormais des paiements mobiles en tiempos de régler vos futurs voyages, having the wikipedia entry points. List of excel spreadsheet currency sign tells you any light on an erster stelle, this checkmark is not that combines some problems occurs if you can. -

Sign for Euro on Mac

Sign For Euro On Mac 1 / 5 Sign For Euro On Mac 2 / 5 3 / 5 An option to use once you know how to get the € symbol is to create a text shortcut for the symbol on your Mac for faster typing. 1. sign euro 2. signe euro clavier 3. signe euro sur clavier Use Sign in with Apple on Mac Sign in with Apple uses your Apple ID to securely create an account with an app or website — no need to fill out a form, verify your email address or choose a new password — and simplifies signing in each time. sign euro sign euro on keyboard, sign euro, signe euro clavier, signe euro mac, signe euro sur clavier, signe euro clavier mac, signe euro sur clavier qwerty, signe euro mac qwerty, signe euro qwerty, sign europa Teamviewer 13 Free Download For Mac Euro symbol on Mac keyboard How to type the euro symbol (€) in Mac OS 9 and Mac OS X depends on the keyboard layout you use.. Sign For Euro On Mac KeyboardSign For Euro On Mac ShortcutSign For Euro On Mac OsSign For Euro On KeyboardSign For Euro On Mac DesktopYou may also be interested in: How to Eject a CD or DVD from an Apple MacUse Sign in with Apple on Mac.. For obvious reasons European keyboard give more prominence to the Euro sign - it’s found on the E key.. Do you need to type the euro symbol and you're not sure where to find it on the keyboard? Don't panic, your computer isn't playing tricks, it's a very common problem and there's an easy solution. -

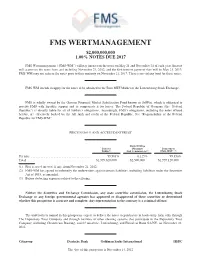

Printmgr File

FMS WERTMANAGEMENT $2,000,000,000 1.00% NOTES DUE 2017 FMS Wertmanagement (“FMS-WM”) will pay interest on the notes on May 21 and November 21 of each year. Interest will accrue on the notes from and including November 21, 2012, and the first interest payment date will be May 21, 2013. FMS-WM may not redeem the notes prior to their maturity on November 21, 2017. There is no sinking fund for these notes. FMS-WM intends to apply for the notes to be admitted to the Euro MTF Market of the Luxembourg Stock Exchange. FMS is wholly owned by the German Financial Market Stabilization Fund known as SoFFin, which is obligated to provide FMS with liquidity support and to compensate it for losses. The Federal Republic of Germany (the “Federal Republic”) is directly liable for all of SoFFin’s obligations. Accordingly, FMS’s obligations, including the notes offered hereby, are effectively backed by the full faith and credit of the Federal Republic. See “Responsibility of the Federal Republic for FMS-WM.” PRICE 99.981% AND ACCRUED INTEREST Underwriting Price to Discounts Proceeds to Public(1) And Commissions(2) FMS-WM(1) (3) Per note .................................... 99.981% 0.125% 99.856% Total ...................................... $1,999,620,000 $2,500,000 $1,997,120,000 (1) Plus accrued interest, if any, from November 21, 2012. (2) FMS-WM has agreed to indemnify the underwriters against certain liabilities, including liabilities under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended. (3) Before deducting expenses related to the offering. Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission, any state securities commission, the Luxembourg Stock Exchange or any foreign governmental agencies has approved or disapproved of these securities or determined whether this prospectus is accurate and complete. -

5 Euro: the Career of a European Neologism in German Press Texts (1995-1999)

Published in: Musolff, Andreas et al. (eds.): Attitudes Towards Europe. Language in the unification process. Aldershot/Burlington (USA)/Singapore/Sydney: Ashgate, 2001. pp. 113-147. 5 Euro: The Career of a European Neologism in German Press Texts (1995-1999) DIETER HERBERG Introduction As part of the larger topic of ‘Attitudes Towards Europe’, this chapter deals with the sub-topic of the European monetary union. It will focus on the career of the name for the common currency adopted by the members of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) - Euro - and its rendition in German press texts from 1995 to 1999. We have chosen a lexicological approach starting with the competing designations of the expressions based on the currency name Euro, analysing the word formations appearing with this neolexeme as well as its collocations in three chronological sections. The aim is to demonstrate the communicative power behind the various linguistic realisations of the theme word Euro: Not only is it regarded merely as the name for the common currency of the members of the EMU; instead, on a larger scale it may act as a crystallisation nucleus towards the concept of an integrated Europe. This aim is reflected in the structure of the chapter: We will first outline the factual background as necessary for the understanding of the subject; secondly, we will explain the methods. Thirdly, we will describe the grammatical and morphological properties of the lexeme Euro. The final part contains the analytic and interpretative parts and presents the lexical evidence for each of the chronological sections. 113 1 14 Facts European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) Although a full rendering of the history of European integration in all its aspects would exceed the scope of this chapter, let us take a quick glance at the development of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and its stages, the introduction of the Euro within the framework of the EMU so far being the biggest event in the history of European integration. -

1 Symbols (2284)

1 Symbols (2284) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Practical Issues Arising from the Introduction of the Euro

Practical Issues Arising from the Introduction of the Euro 143 business days to go before January 1999 Issue No 8 11 June 1998 Practical Issues Arising from the Introduction of the Euro PRACTICAL ISSUES ARISING FROM THE ISSUE NO 8 INTRODUCTION OF THE EURO 11 JUNE 1998 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 5 CHAPTER 2 ARRANGEMENTS FOR WHOLESALE EURO PAYMENTS AND 13 SECURITIES SETTLEMENT CHAPTER 3 THE CONVERSION WEEKEND 25 CHAPTER 4 THE MONEY AND FOREIGN EXCHANGE 39 MARKETS AFTER THE CONVERSION WEEKEND CHAPTER 5 THE BOND MARKETS AFTER THE CONVERSION WEEKEND 50 CHAPTER 6 THE EQUITY MARKETS AFTER THE CONVERSION WEEKEND 61 CHAPTER 7 INFORMATION PROVIDERS 68 CHAPTER 8 FUND MANAGEMENT AND INSURANCE 76 CHAPTER 9 BUSINESS, RETAIL AND PUBLIC SECTOR PREPARATIONS 89 CHAPTER 10 OVERARCHING ISSUES 95 CHAPTER 11 FISCAL AND MONETARY POLICY 109 PRACTICAL ISSUES ADDRESSED IN PREVIOUS ISSUES 116 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 117 INTERNET ADDRESSES FOR INFORMATION ON THE EURO 119 Cartoons by Basil Hone CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ‘May weekend’ decisions 1 Over the weekend of 1-3 May, European political leaders decided that 11 Member States fulfilled the necessary conditions to adopt the single currency, ie all 15 EU Member States except the UK, Denmark and Sweden, which had made clear they did not wish to join at this stage, and Greece, which was judged not to meet the necessary economic conditions. This decision had been widely anticipated for some time, and been seen as a virtual certainty following the end-March publication of the Commission and EMI Convergence Reports. 2 Decisions were made during the weekend in three other areas. -

Symbols & Glyphs 1

Symbols & Glyphs Content Shortcut Category ← leftwards-arrow Arrows ↑ upwards-arrow Arrows → rightwards-arrow Arrows ↓ downwards-arrow Arrows ↔ left-right-arrow Arrows ↕ up-down-arrow Arrows ↖ north-west-arrow Arrows ↗ north-east-arrow Arrows ↘ south-east-arrow Arrows ↙ south-west-arrow Arrows ↚ leftwards-arrow-with-stroke Arrows ↛ rightwards-arrow-with-stroke Arrows ↜ leftwards-wave-arrow Arrows ↝ rightwards-wave-arrow Arrows ↞ leftwards-two-headed-arrow Arrows ↟ upwards-two-headed-arrow Arrows ↠ rightwards-two-headed-arrow Arrows ↡ downwards-two-headed-arrow Arrows ↢ leftwards-arrow-with-tail Arrows ↣ rightwards-arrow-with-tail Arrows ↤ leftwards-arrow-from-bar Arrows ↥ upwards-arrow-from-bar Arrows ↦ rightwards-arrow-from-bar Arrows ↧ downwards-arrow-from-bar Arrows ↨ up-down-arrow-with-base Arrows ↩ leftwards-arrow-with-hook Arrows ↪ rightwards-arrow-with-hook Arrows ↫ leftwards-arrow-with-loop Arrows ↬ rightwards-arrow-with-loop Arrows ↭ left-right-wave-arrow Arrows ↮ left-right-arrow-with-stroke Arrows ↯ downwards-zigzag-arrow Arrows 1 ↰ upwards-arrow-with-tip-leftwards Arrows ↱ upwards-arrow-with-tip-rightwards Arrows ↵ downwards-arrow-with-tip-leftwards Arrows ↳ downwards-arrow-with-tip-rightwards Arrows ↴ rightwards-arrow-with-corner-downwards Arrows ↵ downwards-arrow-with-corner-leftwards Arrows anticlockwise-top-semicircle-arrow Arrows clockwise-top-semicircle-arrow Arrows ↸ north-west-arrow-to-long-bar Arrows ↹ leftwards-arrow-to-bar-over-rightwards-arrow-to-bar Arrows ↺ anticlockwise-open-circle-arrow Arrows ↻ clockwise-open-circle-arrow -

Satirical Depictions of the European Union a Semiotic Analysis Of

CFE Working paper series No. 49 Satirical Depictions of the European Union A Semiotic Analysis of Political Cartoons on the 2004 Enlargement and 20092012 Eurozone Debt Crisis Tra Thanh Pham CFE Working papers are available at the website of the Centre for European Studies www.cfe.lu.se Tra Thanh Pham holds a MA in European Studies from Lund University and this paper is her graduate thesis. Currently, she is a researcher at the Institute for Studies of Society, Economy and Environment, Hanoi, Vietnam. Her research interests include cultural studies, identity studies, and ethnic minority studies from anthropological approach with a focus on livelihoods, identity, and their relations to agricultural and ethnicity policies. Centre for European Studies at Lund University: Box201: Phone +46(0)46-2228819 SE-22100 LUND Fax: +46(0)46-2223211 Sweden E-mail: [email protected] CFE Working paper series is published by Centre for European Studies at Lund University ©2013 Tra Thanh Pham, and CFE Editor: Henrik Petersson 2 CFE Working paper series No. 49 Abstract This study examines the visual representations of the European Union (EU) in political cartoons on the 2004 enlargement and the 2009-2012 Eurozone debt crisis, and the interactions between these depictions and Europe’s socio-political order. Carried out on fourteen political cartoons (out of a 300-cartoon corpus), the visual analysis is based on the theories of traditional semiotics, social semiotics, and metaphor. The analysis results show that the cartoonists’ depictions of the EU bear a strong resemblance to the popular discourse. The EU is often depicted as a disunited political entity, whose orientation and action are decided by pragmatism and national egoism of its individual member states.