Marius Johan Geertsema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Documents and Settings\Msnll\My Documents\Voyagerreports

Swofford Popular Reading Collection September 1, 2011 Title Author Item Enum Copy #Date of Publication Call Number "B" is for burglar / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11994 PBK G737 bi "F" is for fugitive / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11990 PBK G737 fi "G" is for gumshoe / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue 11991 PBK G737 gi "H" is for homicide / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11992 PBK G737 hi "I" is for innocent / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11993 PBK G737 ii "K" is for killer / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11995 PBK G737 ki "L" is for lawless / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11996 PBK G737 li "M" is for malice / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11998 PBK G737 mi "N" is for noose / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11999 PBK G737 ni "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue 12001 PBK G737 ou 10 lb. penalty / Dick Francis. Francis, Dick. 11998 PBK F818 te 100 great fantasy short short stories / edited by Isaac 11985 PBK A832 gr Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg, with an introduction by Isaac Asimov. 1001 most useful Spanish words / Seymour Resnick. Resnick, Seymour. 11996 PBK R434 ow 1022 Evergreen Place / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12010 PBK M171 te 13th warrior : the manuscript of Ibn Fadlan relating his Crichton, Michael, 1942- 11988 PBK C928 tw experiences with the Northmen in A.D. 922. 16 Lighthouse Road / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12001 PBK M171 si 1776 / David McCullough. McCullough, David G. 12006 PBK M133 ss 1st to die / James Patterson. Patterson, James, 1947- 12002 PBK P317.1 fi 204 Rosewood Lane / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. -

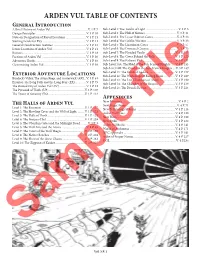

ARDEN VUL TABLE of CONTENTS General Introduction a Brief History of Arden Vul

ARDEN VUL TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction A Brief History of Arden Vul ..................................................V. 1 P. 7 Sub-Level 1: The Tombs of Light ...........................................V. 3 P. 3 Design Principles ...................................................................V. 1 P. 10 Sub-Level 2: The Hall of Shrines ..........................................V. 3 P. 11 Note on Designation of Keyed Locations ...........................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 3: The Lesser Baboon Caves ...............................V. 3 P. 23 Starting Levels for PCs ..........................................................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 4: The Goblin Warrens........................................ V. 3 P. 33 General Construction Features ...........................................V. 1 P. 12 Sub-Level 5: The Lizardman Caves .....................................V. 3 P. 57 Iconic Locations of Arden Vul .............................................V. 1 P. 14 Sub-Level 6: The Drowned Canyon ....................................V. 3 P. 73 Rumors ....................................................................................V. 1 P. 18 Sub-Level 7: The Flooded Vaults .......................................V. 3 P. 117 Factions of Arden Vul ...........................................................V. 1 P. 30 Sub-Level 8: The Caves Behind the Falls ..........................V. 3 P. 125 Adventure Hooks ...................................................................V. 1 P. 48 Sub-Level 9: The Kaliyani Pits ...........................................V. -

Marius the Epicurean: His Sensations and Ideas

MARIUS THE EPICUREAN: HIS SENSATIONS AND IDEAS. VOLUME I OF II WALTER PATER, 1885. E-Texts for Victorianists E-text Editor: Alfred J. Drake, Ph.D. Electronic Version 1 / Date 6-24-02 This Electronic Edition is in the Public Domain. DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES [1] I DISCLAIM ALL LIABILITY TO YOU FOR DAMAGES, COSTS AND EXPENSES, INCLUDING LEGAL FEES. [2] YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE OR UNDER STRICT LIABILITY, OR FOR BREACH OF WARRANTY OR CONTRACT, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. [3] THE E-TEXTS ON THIS SITE ARE PROVIDED TO YOU “AS-IS”. NO WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, ARE MADE TO YOU AS TO THE E-TEXTS OR ANY MEDIUM THEY MAY BE ON, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. [4] SOME STATES DO NOT ALLOW DISCLAIMERS OF IMPLIED WARRANTIES OR THE EXCLUSION OR LIMITATION OF CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, SO THE ABOVE DISCLAIMERS AND EXCLUSIONS MAY NOT APPLY TO YOU, AND YOU MAY HAVE OTHER LEGAL RIGHTS. PRELIMINARY NOTES BY E-TEXT EDITOR: Reliability: Although I have done my best to ensure that the text you read is error-free in comparison with the edition chosen, it is not intended as a substitute for the printed original. The original publisher, if still extant, is in no way connected with or responsible for the contents of any material here provided. The viewer should bear in mind that while a PDF document may approach facsimile status, it is not a facsimile—it requires the same careful proofreading and editing as documents in other electronic formats. -

An Interview with Damon Knight

No. 34 March 1972 An Interview With Damon Knight Conducted by Paul Walker* What has been the most interesting development in science fiction since 1960? What has been the most obnoxious, to you, personally? The most interesting development would have to be the movement of com mercial science fiction back toward the standards of literary science fiction from which it diverged about 70 years ago. This is what's putting some life back into the field for the first time since the early 50's. The least pleasant develop ment, I guess, would be Sol Cohen's reprint magazines. One way of measuring the health of the field is by counting the number of good new writers who appear in it each year. I wrote a piece about this for the Clarion anthology; the chart that goes with it shows a peak (24) in 1930, another (17) in 1941, another (28) in 1951, and then a long slow decline to 1965, the last year for which I had records — the figure there was 1. I have not been able to draw the rest of that line, but I think I know what it would look like. How has the role of editor fared in the same time? Generally speaking, if you're talking about the magazines and most of the paperbacks, I think science fiction editing has been a downhill thing since 1950 — more routine, less rewarding, less effective. Struggling to keep dead things afloat is no fun for anybody. As far as I'm concerned, my experience is not typical. -

Riverside Quarterly V4#2 Sapiro 1970-01

78 RIVERSIDE QUARTERLY RQ MISCELLANY January 1970 Vol. 4, No. 2 BALLARD BIBLIOPHILES Editors: Leland Sapiro, Jim Hannon, David Lunde William Blackboard, Redd Boggs, Jon White If your curiosity is roused by "Homo Hydrogenesis" this issue— or if you've a previous interest in French Symbolism and Jim Bal Send poetry to: 1179 Central Ave., Dunkirk, NY 14048 lard's latter-day extension thereof—you'll profit by consulting Send other correspondence to: Box 40 Univ. Sta., Regina the last few issues of Pete Weston’s Speculation (31 Piewall Ave, Masshouse Lane, Birmingham-30, UK; 3 copies 7/6d or $1 USA). The current number even contains some non—Baudelarian correspondence TABLE OF CONTENTS from Mr. Ballard himself. RQ Miscellany............................................................................ 79 INEXCUSABLE OMISSIONS—FIRST SERIES Challenge and Response: Last time (p.73) I forgot to list the address—55 Bluebonnet Foul Anderson's View of Man.. Sandra Mleael... 80 Court, Lake Jackson, Texas 77566—of Joanne Burger, who offers the N.E.T. tapes, "H.G. Wells, Man of Science." I also failed to say Aphelion.................................... ................Bob Parkinson... 96 that Michel Desimones article (pp. 48-51) was taken from the dou ble editioji of Philip Jose Farmer's Les Amants Etrangers and Homo Hydrogenasia: L'Uniyers AL*Envers (The Lovers and inside Outside), Club du Liv Notes on J.G. Ballard..............Nick Perry..............98 re Anticipation, Paris, 1968. So far, contact with Mr. Desimon has .................... Roy Wilkie been impossible--which is just as well, since in addition to the omission just cited I mis-spelled his name twice and possibly com The Presence of Angels....................... -

Volume 4, No. 2 (2013)

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Florica Bodi ştean EDITORIAL SECRETARY Adela Dr ăucean EDITORIAL BOARD: Adriana Vizental Călina Paliciuc Alina-Paula Nem ţuţ Alina P ădurean Simona Rede ş Melitta Ro şu GRAPHIC DESIGN Călin Lucaci ADVISORY BOARD: Acad. Prof. Lizica Mihu ţ, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Acad. Prof. Marius Sala, PhD, “Iorgu Iordan – Al. Rosetti” Linguistic Institute Prof. Larisa Avram, PhD, University of Bucharest Prof. Corin Braga, PhD, “Babe ş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca Assoc. Prof. Rodica Hanga Calciu, PhD, Charles-de-Gaulle University, Lille III Prof. Traian Dinorel St ănciulescu, PhD, “Al. I. Cuza” University of Ia şi Prof. Ioan Bolovan, PhD, “Babe ş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca Assoc. Prof. Sandu Frunz ă, PhD, “Babe ş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca Prof. Elena Prus, PhD, Free International University of Moldova, Chi şin ău Assoc. Prof. Jacinta A. Opara, PhD, Universidad Azteca, Chalco – Mexico Prof. Nkasiobi Silas Oguzor, PhD, Federal College of Education (Technical), Owerri – Nigeria Assoc. Prof. Anthonia U. Ejifugha, PhD, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri – Nigeria Prof. Raphael C. Njoku, PhD, University of Louisville – United States of America Prof. Shobana Nelasco, PhD, Fatima College, Madurai – India Prof. Hanna David, PhD, Tel Aviv University, Jerusalem – Israel Prof. Ionel Funeriu, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Prof. Florea Lucaci, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Prof. Monica Ponta, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Prof. Corneliu P ădurean, PhD, “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad Address: Str. Elena Dr ăgoi, nr. 2, Arad Tel. +40-0257-219336 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ISSN 2067-6557 ISSN-L 2247/2371 2 Faculty of Humanistic and Social Sciences of “Aurel Vlaicu”, Arad Volume IV, No. -

Caius Marius and Roman Factional Politics James J

CAIUS MARIUS AND ROMAN FACTIONAL POLITICS By JAMES J. HARRISON Bachelor of Arts Cameron State College Lawton, Oklahoma 1970 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS July, 1971 / I CAIUS MARIUS AND RDMAN FACTIONAL POLITICS" Thesis Approved: 903892 ii PREFACE Historians have recently given increased consideration to the life of Caius Marius. Heretofore he was recognized as a military leader and statesman of Rome during the second and first centuries, BoC., but little was really known of the man himselfo His military ability has long been recognized by historians and his contributions to the development of the Roman anny have often been recounted. His activities :in the political field are less auspicious and, hence, more obscure. Recent findings reveal Marius as an investor and financier of high standing in Rome. He is currently being shown as having had far more inUuence in the economic life of Rome than was previously suspected. The sum of his attributes and accomplishments give cause to question why such an important Rom~ public figure could be forced to exile himself from Rome. The question is heightened in view of Marius' almost unprecedented position in the city at the end of the Ciwbric Wars. The pop'Ulace and his veterans went so far as to compare Marius to the god Dionysus, and to declare him "The Third Founder of Rome" after Romulus and Camillus. Yet, Marius deliberately chose exile in preference to the scorn of his fellow-citizens in 99 B.C., after the actions of his political agents had outraged the Romans of economic and social consequence. -

Poul and Karen Anderson Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8sn0gm2 No online items Poul and Karen Anderson papers Finding aid prepared by Andrew Lippert, Special Collections Processing Archivist. Special Collections & University Archives The UCR Library P.O. Box 5900 University of California Riverside, California 92517-5900 Phone: 951-827-3233 Fax: 951-827-4673 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucr.edu/libraries/special-collections-university-archives © 2019 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Poul and Karen Anderson papers MS 040 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Poul and Karen Anderson papers Date (inclusive): 1925-2018 Date (bulk): 1950-2010 Collection Number: MS 040 Creator: Anderson, Karen, 1932-2018 Creator: Anderson, Poul, 1926-2001 Extent: 54.17 linear feet(73 boxes, 41 flat file folders) Repository: Rivera Library. Special Collections Department. Riverside, CA 92517-5900 Abstract: The collection consists of the personal and professional papers of science fiction and fantasy authors Poul and Karen Anderson. These materials document the writing and publishing process and their involvement with the science fiction community and other organizations such as the Society for Creative Anachronism and Sherlockiana groups. Items in the collection include correspondence, manuscript drafts, notes, diaries, personal records, artwork, memorabilia and ephemera from various conventions and events. Languages: The collection is primarily in English with a small amount of materials in Danish. Access This collection is open for research. Some materials have been restricted at the request of the donor until 2044 and are noted as such within this finding aid. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the University of California, Riverside Libraries, Special Collections & University Archives. -

Vampire Chronicles

Publisher’s Note This new edition of the Critical Survey of Science Each article discusses an individual book or series Fiction & Fantasy Literature is a three-volume set and often comments on other works by the same offering plot summaries and analyses of 842 of author. Individual articles open with basic reference the most popular and frequently taught science information in a ready-reference format: author’s fiction and fantasy books and series. Articles are name, birth and death dates, identification of the alphabetically arranged by titles and range from work as either science fiction or fantasy, subgenre, such childhood fantasy classics as Lewis Carroll’s type of work (such as drama, novel, novella, series, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and L. or story), time and location of plot, and date of first Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) publication. The main body of each essay contains to such pioneering science-fiction works as H. G. “The Story” which summarizes the work’s plot and Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898) and modern identifies major characters, and “Analysis” which science-fiction and fantasy classics as Robert Hein- offers a critical interpretation of the title and iden- lein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966) and J. R. tifies literary devices and themes used in the work. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy (1954-1955). Readers will find several reference tools at the Among other prominent writers whose works end of Volume 3: are included are Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Frank Herbert, John Crowley, Ellen Kushner, and • Annotated bibliography arranged by subject; C. -

Stars Without Number

STARS WITHOUT NUMBER CORE EDITION For Eden, who gave me a reason. © 2010-2011, Sine Nomine Publishing ISBN 978-1-936673-19-3 Written by Kevin Crawford. Cover art by Jimmy Zhang. Interior art provided by NASA, ESA, and F. Paresce (INAF-IASF, Bologna, Italy), R. O’Connell (University of Virginia, Charlottesville), The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI), and the Wide Field Camera 3 Science Oversight Committee. Interior art by David Sharrock, Tamás Baranya, Cerberus Illustrations, Pawet Dobosz, Angela Harburn, Andy Hepworth, Szilvia Huszar, Peter Szabo Gabor, Eric Lofgren, Bradley K McDevitt, Jeff Preston, Louis Porter Jr. Design, Shaman’s Stockart, Maciej Zagorski, and The Forge Studios, used with permission. Some artwork copyright Talisman Studios (c) 2007, used with permission. All rights reserved. Some maps created with Hexographer; http://www.hexographer.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................4 Character Creation ............................................................................................6 Psionics ...........................................................................................................24 Equipment ......................................................................................................32 Systems ...........................................................................................................58 The History of Space .......................................................................................70 -

Perry Anderson

Perry Anderson NLB Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism 0 NLB, x974 NLB, 7 Carlisle Street, London, WI Type set in Monotype Fournier and printed by Western Printing Services Ltd, Bristol Foreword 7 PART ONE I. Classical Antiquity I. The Slave Mode of Production 28 2. Greece 29 3. The Hellenistic World 45 4. Rome 53 II. The Transition I. The Germanic Background I 07 2. The Invasions z 12 3. Towards Synthesis 228 PART TWO I. Vestern Europe I. The Feudal Mode of Production 247 2. Typology of Social Formations 254 3. The Far North 273 4. The Feudal Dynamic 282 5. The General Crisis 197 II. Eastern Europe I. East of the Elbe 223 2. The Nomadic Brake 227 3. The Pattern of Development 229 4. The Crisis in the East 246 5. South of the Danube 265 Index of Names 294 Index 6f Authorities 302 Foreword Some words are necessary to explain the scope and intention of this essay. It is conceived as a prologue to the longer study, whose subject- matter follows immediately on it: Lineages of the Absolutist State. The two books are articulated directly into each other, and ultimately suggest a single argument. The relationship between the two - antiquity and feudalism on the one hand, and absolutism on the other - is not immediately apparent, in the usual perspective of most treat- ments of them. Normally, ancient history is separated by a professional chasm from mediaeval history, which very few contemporary works attempt to span: the gulf between them is, of course, institutionally entrenched in both teaching and research. -

Reforming Medicine in Sixteenth Century Nuremberg by Hannah Saunders Murphy Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Thomas A

Reforming Medicine in Sixteenth Century Nuremberg By Hannah Saunders Murphy A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thomas A Brady, Jr, Co-chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan, Co-chair Professor Thomas Laqueur Professor Ethan Shagan Professor Elaine Tennant Fall 2012 Reforming Medicine in Sixteenth Century Nuremberg © 2012 by Hannah Saunders Murphy All rights reserved. 1 Abstract Reforming Medicine in Sixteenth Century Nuremberg by Hannah Saunders Murphy Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Thomas A. Brady Jr. & Jonathan Sheehan, Co-Chairs In 1571 the Nuremberg physician, Joachim Camerarius (1534-1598), submitted for the appraisal of his city's Senate, a substantial manuscript titled "Short and Ordered Considerations for the Formation of a Well-Ordered Regime.” As one of these 'considerations', he petitioned the Council to establish a Collegium medicum: an institutional body that would operate under the council's mandate to regulate and reform the practice of medicine in the Imperial City of Nuremberg. Although never published, this text became the manifesto of an ongoing movement for the reform and reorganization of medicine throughout the sixteenth century. This 'medical reformation' was a professional claim to social status and political authority on the part of academically educated municipal physicians. More elusively and more importantly,