Appendix E Aboriginal Archaeology Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stratigraphic Imprint of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in Eastern Australia: a Record of Alternating Glacial and Nonglacial Climate Regime

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences of 1-2008 Stratigraphic imprint of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in eastern Australia: A record of alternating glacial and nonglacial climate regime Christopher R. Fielding University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Tracy D. Frank University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Lauren P. Birgenheier University of Nebraska-Lincoln Michael C. Rygel State University of New York, College at Potsdam Andrew T. Jones Geoscience Australia, Canberra See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Fielding, Christopher R.; Frank, Tracy D.; Birgenheier, Lauren P.; Rygel, Michael C.; Jones, Andrew T.; and Roberts, John, "Stratigraphic imprint of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in eastern Australia: A record of alternating glacial and nonglacial climate regime" (2008). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 103. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Christopher R. Fielding, Tracy D. Frank, Lauren P. Birgenheier, Michael C. Rygel, Andrew T. Jones, and John Roberts This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ geosciencefacpub/103 Published in Journal of the Geological Society 165:1 (January 2008), pp. -

The Wreck of the Dunbar N FRIDAY, August 21, 1857, the Crew of an Incoming O Vessel Noticed Masses of Wreckage and Debris Floating About Between the Sydney Heads

~Y-dneJ.:'S worst shiP-P-ing disaster saw onlY- one of 122 survive The wreck of the Dunbar N FRIDAY, August 21, 1857, the crew of an incoming O vessel noticed masses of wreckage and debris floating about between the Sydney Heads. Tnere were ship's timbers, bales of goods. children's toys. HISTORICAL even furniture - and, later in the day, more items began turning up all over the harbor. It seemed certain that a ship had been wrecked near the harbor entrance and two pilots at Watson's Bay began searching along the cliffs and around the rocks at South Head. They soon saw spars, cargo and bodies floating in the waves offshore. The identity of the ill-fated ship was not had come perilously close to learned until later in the the rocky coast. Just before midnight. there day, however, when a was a momentary wink of light mailbag was washed up at thro\l.gh the murk. Its direction Watson's Bay marked with indiCated that the ship had the name Dunbar. passed to the north of the So was discovered Sydney's lighthouse, and Captain Green worst shipping disaster and, knew he was close to the indeed, one of the most tragic entrance to Sydney harbor. shipwrecks in Australia's Later, it was suggested that history. All but one of the 122 the skipper had mistaken The passengers and crew on the Gap for the Heads and turned I Dunbar - 81 days out from to port too soon. From James Johnson, who survived by clinging to a rock ledge at London - perished when it evidence subsequently given The Gap, and told of the Dunbar's final hours. -

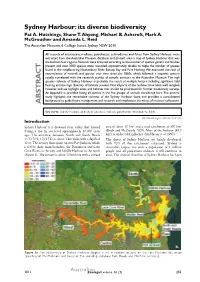

Page 1 Sydney Harbour: Its Diverse Biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings

Sydney Harbour: its diverse biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings, Shane T. Ahyong, Michael B. Ashcroft, Mark A. McGrouther and Amanda L. Reid The Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010 All records of crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms and fishes from Sydney Harbour were extracted from the Australian Museum database, and plotted onto a map of Sydney Harbour that was divided into four regions. Records were analysed according to the number of species, genera and families present and over 3000 species were recorded, approximately double to triple the number of species found in the neighbouring Hawkesbury River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking. We examined the rate of accumulation of records and species over time since the 1860s, which followed a stepwise pattern usually correlated with the research activity of specific curators at the Australian Museum. The high species richness of Sydney Harbour is probably the result of multiple factors including significant tidal flushing and the high diversity of habitats present. Not all parts of the harbour have been well sampled, however, and we highlight areas and habitats that should be prioritised for further biodiversity surveys. An Appendix is provided listing all species in the five groups of animals considered here. The present study highlights the remarkable richness of the Sydney Harbour fauna and provides a consolidated background to guide future management and research, and emphasises the values of museum collections. ABSTRACT Key words: Sydney Harbour, diversity, crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms, fishes http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2012.031 Introduction Sydney Harbour is a drowned river valley that formed area of about 50 km2 and a total catchment of 500 km2 during a rise in sea level approximately 10,000 years (Birch and McCready 2009). -

Title Page.Indd

AN ANALYSIS OF RELATIVE SPATIAL PATTERNS OF HOUSING AFFORDABILITY AND EMPLOYMENT IN SYDNEY AND ASSOCIATED PLANNING STRATEGIES LAUREN McMAHON 2006 Undergraduate Thesis Bachelor of Planning University of New South Wales Lauren McMahon Bridging the Gap ABSTRACT The notion of spatial mismatch first emerged as an academic concept in 1968, predominately as an observation of the patterns of development in North American cities, however it has recently become an observation of patterns of development across the globe. The spatial mismatch theory highlights the effects of the geographic differential between where particular social groups are concentrated in the housing market and the effects this had on their relative employment opportunities. As a result of these spatial patterns low income households have limited access to employment opportunities and are often forced into unemployment. Consequently, social polarisation of cities affected by spatial mismatch has occurred which has seen a social disadvantaged class emerge, characterised by low income levels, employment exclusion, transport poverty, locational inaccessibility and low education levels. This thesis explores the Australian context of spatial mismatch with a focus on Sydney as a case study. The historical urban development patterns of Australia will be detailed which have laid the foundations for the emerging spatial mismatch in Sydney. The thesis will analysis the Metropolitan Strategy in terms of its ability to address the challenges associated with spatial mismatch in Sydney. Lauren -

Social Context

Dreamtime Superhighway: an analysis of Sydney Basin rock art and prehistoric information exchange 3 SOCIAL conteXT While anthropology can help elucidate the complexity of cultural systems at particular points in time, archaeology can best document long-term processes of change (Layton 1992b:9) In the original thesis one chapter was dedicated to the ethnohistoric and early sources for the Sydney region and another to previous regional archaeological research. Since 1994, Valerie Attenbrow has published both her PhD thesis (1987, 2004) and the results of her Port Jackson Archaeological Project (Attenbrow 2002). More recent, extensive open area excavations on the Cumberland Plain done as cultural heritage management mitigations (e.g. JMcD CHM 2005a, 2005b, 2006) have also altered our understanding of the region’s prehistory. As Attenbrow’s Sydney’s Aboriginal Past (2002) deals extensively with ethnohistoric evidence from the First Fleet and early days of the colony the ethnohistoric and historic sources explored for this thesis have been condensed to provide the rudiments for the behavioral model developed for prehistoric Sydney rock art. The British First Fleet sailed through Sydney Heads on 26 January 1788. Within two years an epidemic of (probably) smallpox had reduced the local Aboriginal population significantly – in Farm Cove the group which was originally 35 people in size was reduced to just three people (Phillip 1791; Tench 1793; Collins 1798; Butlin 1983; Curson 1985; although see Campbell 2002). This epidemic immediately and irreparably changed the traditional social organisation of the region. The Aboriginal society around Port Jackson was not studied systematically, in the anthropological sense, by those who arrived on the First Fleet. -

Global Coal Gap Between Permian–Triassic Extinction and Middle Triassic Recovery of Peat-Forming Plants

Global coal gap between Permian–Triassic extinction and Middle Triassic recovery of peat-forming plants Gregory J. Retallack Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1272 John J. Veevers School of Earth Sciences, Macquarie University, New South Wales 2109, Australia Ric Morante } ABSTRACT A number of possible explanations for the coal or permineralized peat. Veevers et al. coal gap have been advanced. Land masses (1994a) introduced the term ‘‘coal gap’’ for Early Triassic coals are unknown, and of the world may have been riding too high a sharp break between thick and widespread Middle Triassic coals are rare and thin. The with respect to sea level for the accumu- coal up to the Permian-Triassic boundary, Early Triassic coal gap began with extinc- lation of peat (Daragan-Sushchov, 1989; lack of coal in the Early Triassic, followed by tion of peat-forming plants at the end of the Faure et al., 1995). Naturally acidic swamps thin and uncommon coals in the Middle Permian (ca. 250 Ma), with no coal known may have been overwhelmed by additional Triassic and thick and widespread coals in anywhere until Middle Triassic (243 Ma). acid, such as sulfuric acid from SO2 of mas- the Late Triassic (Fig. 1). The coal gap thus Permian levels of plant diversity and peat sive eruptions of the Siberian Traps (Mc- includes an absolute gap in the Early Tri- thickness were not recovered until Late Cartney et al., 1990), or nitric acid from NOx assic (Scythian) and recovery extending over Triassic (230 Ma). Tectonic and climatic ex- generated by impact of a large extraterres- the Middle Triassic (Anisian and Ladinian). -

February – March

BMW Sydney, Rushcutters Bay. The legs you see in this picture be ong to John. His job is to make sure when you drive away after a service at BMW Sydney, your car looks as good as the day you drove it off the showroom floor. And we can honestly say, when it comes to detail, no one is as driven as John. Of course, he's not alone. He's only one of five staff dedicated to this sole task. And obviously, we do mean dedicated. It's quite selfish really, but we've always believed that if you look good, so do we. From the way we service your car to the way we serve you a coffee while you wait, it's what makes BMW Sydney a world of BMW. BMW Sydney, 65 Craigend Street, Rushcutters Bay. 9334 4555. www.bmwsydney.com.au 1999 Telstra Sydney to Hobart A TIME TO REMEMBER 4 In the fastest race in 55 years, the Volvo 60 Nokia, a Danish/Australian entry, slashed the record for the Telstra Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race while 15 other yachts also broke Morning Glory's time. YES TO YENDYS 8 IMS Overall winner of the 1999 Telstra Sydney to Hobart, the Farr 49 Yendys, had raced for only nine days , including the Hobart, when she crossed the line on the Derwent River to clinch victory for owner/skipper Geoffrey Ross. TAILENDING THE FLEET 12 The story of the race aboard the 22-year-old 33-footer Berrimilla, the last yacht to complete the race to Hobart, taking seven days 10 hours and logging 920 nautical miles for the rhumbline course of 630 mile. -

MIDDLE HEAD As a NSW DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION FIELD STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL CENTRE

MIDDLE HEAD as a NSW DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION FIELD STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL CENTRE The NSW Department of Education has 22 Environmental Education Centres offering curriculum based field work experiences to help students and teachers in a wide variety of subjects. The Centres deliver innovative and contextually relevant teaching and learning programs. Programs are tailored to fit the needs of students and the curriculum These centres usually cater for all NSW Department of Education Schools K-12. My late husband, Donald Henry Goodsir OAM, worked for the Education Department for over 40 years and was the Director of Schools responsible for Environmental Education at one stage in his career. He personally established 3 such Field Studies Centres – the Warrumbungle Centre outside of Coonabarabran, Botany Bay and Observatory Hill. Each Field Study Centre is unique and located in a specific environment. A Middle Head location would offer students from all of NSW an opportunity to focus especially on the early settlement of Sydney Harbour, Australia’s military history, indigenous culture, Sydney Harbour’s marine environment and geography. This would be particularly beneficial for students from the western suburbs and country locations. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As a trained teacher of Geography and History working with the NSW Department of Education for over 30 years, I can recognize the enormous educational potential of this Middle Head site to allow students to physically walk through time. It is a ready-made indoor/outdoor classroom covering a range of curriculum areas. The educational benefits for all students arising from such an experience would be invaluable especially to those who live far removed from this area. -

'The Wreck of the Dunbar and a North Shore Connection' with Historian John Lanser by James Merrington

'The wreck of the Dunbar and a North Shore connection' with Historian John Lanser By James Merrington John Lanser gave an excellent and compelling presentation about the wreck of the Dunbar to 55 attendees on 27 February. The story: the Dunbar was launched in 1853 for London shipowner Duncan Dunbar. She was built for trade to Australia in response to the Australian gold rushes. The Dunbar was on her second voyage to Sydney, when on the night of 20 August 1857 after an 81-day voyage, the ship approached the entrance to Port Jackson from the south. Heavy rain and a fierce Southerly gale made navigating difficult and the ship's captain, James Green, mistook his position and drove the ship on to rocks some 400 metres south of the Gap. There were 59 crew and 63 passengers on board. The ship was driven against the cliffs of South Head and rapidly broke apart. The force of the gale caused the Dunbar to break up. There was only one survivor, James Johnson, who managed to get ashore and find refuge on a rock ledge. He was found alive some 36 hours after the ship foundered; the remainder of the passengers and crew drowned and their bodies and the ship’s wreckage filled the harbour. Lanser also recounted how many in Sydney were affected by the wreck. A procession of carriages transported the dead past 20,000 people who silently lined the streets to St Stephen’s Church in Camperdown where a mass funeral was held. Shops closed and a day of public mourning was declared. -

Dunbar – August 1857

Information Sheet Woollahra Library Local History 4 Centre The Loss of the Dunbar – August 1857 Time: about 12:00 midnight, on Details of the ship: - wooden, three masted square the evening of 20th – 21st rigged ship of 1,321 tons. August, 1857. - waterline length : 201feet (59m). Place: on the rocky reef below the - beam (width) : 35feet (10m). Outer South Head of Port - built in the yards of James Laing, and Jackson, about 500m launched in 1853. south of ‘The Gap’. Survivors: one, Able Seaman James Command: Captain James Green Johnson Owner: Duncan Dunbar, of London Victims: 121 Voyage : Departed Plymouth, 31st May, 1857. Wrecked just short of her destination (Sydney) 81 days later. The clipper Dunbar, on the eighty-first day of her second voyage to New South Wales, arrived off Botany Bay in the early evening of 20th August 1857. The weather conditions were already bad and worsening as the Dunbar made her way northwards up the coast towards her destination – Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour). Many of those on board the Dunbar were residents of the colony of New South Wales, returning after spending time in England. They were within hours of being reunited with their families, friends and homes after almost three months at sea – or so they believed. The weather, by nightfall, was extreme. Fifty years later, Henry Packer, a former signalman who had been stationed in 1857 at the South Head Signal Station, could still recall the force of the wind, rain and seas on the night when the Dunbar was lost. Packer described the seas as ‘mountainous’, and the sky hung with ‘dirty, leaden clouds, the sort that mariners dread’. -

The Geology of NSW

The Geology of NSW The geological characteristics and history of NSW with a focus on coal seam gas (CSG) resources A report commissioned for the NSW Chief Scientist’s Office, May, 2013. Authors: Dr Craig O’Neill1, [email protected] Dr Cara Danis1, [email protected] 1Department of Earth and Planetary Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, 2109. Contents A brief glossary of terms i 1. Introduction 01 2. Scope 02 3. A brief history of NSW Geology 04 4. Evolution of the SydneyGunnedahBowen Basin System 16 5. Sydney Basin 19 6. Gunnedah Basin 31 7. Bowen Basin 40 8. Surat Basin 51 9. ClarenceMoreton Basin 60 10. Gloucester Basin 70 11. Murray Basin 77 12. Oaklands Basin 84 13. NSW Hydrogeology 92 14. Seismicity and stress in NSW 108 15. Summary and Synthesis 113 ii A brief Glossary of Terms The following constitutes a brief, but by no means comprehensive, compilation of some of the terms used in this review that may not be clear to a non‐geologist reader. Many others are explained within the text. Tectonothermal: The involvement of either (or both) tectonics (the large‐scale movement of the Earth’s crust and lithosphere), and geothermal activity (heating or cooling the crust). Orogenic: pertaining to an orogen, ie. a mountain belt. Associated with a collisional or mountain‐building event. Ma: Mega‐annum, or one million years. Conventionally associated with an age in geochronology (ie. million years before present). Epicratonic: “on the craton”, pertaining to being on a large, stable landmass (eg. -

Dawes Point Geographical Review

Dawes Point Geographical Review To the Royal Australian Historical Society, Geographical Society of NSW, and the Geographical Names Board of NSW From Davina Jackson PhD, M.Arch, FRGS, MRAHS 19 February 2018 Synopsis Leading Sydney historians have noted persistent confusions about the appropriate mapping of Dawes Point—as several places of colonial history significance and a suburb gazetted in 1993. This report suggests that Lt. William Dawes’s science, defence, construction and linguistic contributions to colonial Sydney would be appropriately honoured by: —Recognising Dawes Point as all the public pedestrian areas occupying the western headland of Sydney Cove from the north headland of Campbells Cove to Ives Steps beside Pier 1 on Walsh Bay; —Renaming Hickson Road Reserve as part of the existing Dawes Point Reserve—which also has been identified in state government documents as Dawes Point (Tar ra) Park*; —Including all the Dawes Point public open space area in the suburb of The Rocks (which currently includes only Hickson Road Reserve); —Delisting the microsuburb of Dawes Point (2016 pop. 357), which since 1993 has overlapped half of the Walsh Bay conservation zone (SREP 16 1989-2009) and parts of the Millers Point and Dawes Point Park conservation zones; and —Including Lower Fort Street (west side) and Trinity Street in the suburb and conservation zone of Millers Point (LEP 2012), to conceptually rejoin Fort Street on Observatory Hill. * See Figs. 30-32 from Mary Knaggs, 2011, Dawes Point (Tar ra) Conservation Management Plan, Sydney: NSW Government Architect’s Office, and earlier Dawes Point CMPs. Summary Dawes Point has been inconsistently mapped since the early 1800s.