View PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Santería in a Globalized World: a Study in Afro-Cuban Folkloric Music" (2018)

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-30-2018 Santería in a Globalized World: A Study in Afro- Cuban Folkloric Music Nathan Montgomery Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the African History Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Latin American History Commons, Music Education Commons, Music Practice Commons, Oral History Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Montgomery, Nathan, "Santería in a Globalized World: A Study in Afro-Cuban Folkloric Music" (2018). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 123. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/123 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nathan Montgomery 4/30/18 IHRTLUHC SANTERÍA IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD: A STUDY OF AFRO-CUBAN FOLKLORIC MUSIC ABSTRACT The Yoruban people of modern-day Nigeria worship many deities called orichas by means of singing, drumming, and dancing. Their aurally preserved artistic traditions are intrinsically connected to both religious ceremony and eVeryday life. These forms of worship traVeled to the Americas during the colonial era through the brutal transatlantic slaVe trade and continued to eVolVe beneath racist societal hierarchies implemented by western European nations. Despite severe oppression, Yoruban slaves in Cuba were able to disguise orichas behind Catholic saints so that they could still actiVely worship in public. This initial guise led to a synthesis of religious practice, language, and artistry that is known today as Santería. -

1 Peseta. GIJQH

PRIMERA EDICIÓN fíQtio: 1 peseta. GIJQH ^PRESTA. DEL MaSBl 3 cargo de I. Cai'bnjoJ. Rastro, 24. 8 2 1893 92S2 \ INCOHERENCIAS POÉTICAS, ,1/ Es propiedad del Autor, quien se reserva todos los derechos que la Ley le concede. %EE\NANDEZ ?||ASAD O. GIJON IMPRÉNTA DEL MUSEL d cargo de I. Carbajal Rastro, 24 1892 ftító- "El Síutor. EL AUTOR AL LECTOR La amistad quería llenar este vacío: á ello me opuse. La crítica no debía hablar de esta pequeñez antes que el público; así que no la busqué aunque prometiese benevolencias. El autor habla por seguir la corriente, por dar algunas explicaciones; • pero sin osar alabarse; que la alabanza estaría reñida con el texto, y al público le parecería avilantez un elogio asaz interesado. Este librejo es una síntesis de anarquías filosóficas y sociales, en parte conocidas del público. La lógica debe de aburrirse en el Parnaso, y por eso los que hacemos versos nos contradecimos con frecuencia. VI INCOHEEENCIAS Nuestro cerebro se asemeja á un kaleidos- copio. En este curioso aparato de óptica, el movimiento descompone y recompone las figuras quebrando lineas y combinando co• lores. La luz siempre es lá misma, los crista• les también; pero las figuras, no: varían siempre. El kaleidoscopio, imitando al cerebro, da idea de lo subjetivo y lo objetivo. Esto es in• variable; aquello no. Cada sujeto percibe á su modo, ve las cosas á través de sus nervios, y según éstos sean y según vibren (pase la pa• labra), sentirá y pensará. El cristal con que se mira es mucho, porque es el color. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E684 HON

E684 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 17, 2009 TRIBUTE TO KENT OLSON, EXECU- Not only will this initiative increase Internet Madam Speaker, I encourage my col- TIVE DIRECTOR OF THE PROFES- speed and accessibility for customers, but per- leagues to join me in wishing my brothers of SIONAL INSURANCE AGENTS OF haps more importantly it will create 3,000 new Omega Psi Phi Fraternity a successful political NORTH DAKOTA jobs. summit as these men continue to build a Over the next ten years, AT&T also plans to strong and effective force of men dedicated to HON. EARL POMEROY create or save an additional one thousand its Cardinal Principles of manhood, scholar- jobs through a plan to invest $565 million in OF NORTH DAKOTA ship, perseverance, and uplift. replacing its current fleet of vehicles with IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES f 15,000 domestically manufactured Com- Tuesday, March 17, 2009 pressed Natural Gas and alternative fuel vehi- REMEMBERING THE LIFE OF Mr. POMEROY. Madam Speaker, I rise to cles. MUSIC IMPRESARIO RALPH honor the distinguished career of Kent Olson. Research shows that this new fleet will save MERCADO I am pleased to have known Kent Olson for 49 million gallons of gasoline over the next ten the many years he served as the Executive years. It also will reduce carbon emissions by HON. CHARLES B. RANGEL Director of the Professional Insurance Agents 211,000 metric tons in this same time frame. OF NEW YORK of North Dakota working with him on important Madam Speaker, I applaud AT&T for its ini- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES tiative in taking the lead in the movement to insurance issues for North Dakota farmers. -

Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12

***For Immediate Release*** 22nd Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12 - Sunday, August 14, 2011 Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Ticket Info: www.jazzfest.sanjosejazz.org Tickets: $15 - $20, Children Under 12 Free "The annual San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest] has grown to become one of the premier music events in this country. San Jose Jazz has also created many educational programs that have helped over 100,000 students to learn about music, and to become better musicians and better people." -Quincy Jones "Folks from all around the Bay Area flock to this giant block party… There's something ritualesque about the San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest.]" -Richard Scheinan, San Jose Mercury News "San Jose Jazz deserves a good deal of credit for spotting some of the region's most exciting artists long before they're headliners." -Andy Gilbert, San Jose Mercury News "Over 1,000 artists and 100,000 music lovers converge on San Jose for a weekend of jazz, funk, fusion, blues, salsa, Latin, R&B, electronica and many other forms of contemporary music." -KQED "…the festival continues to up the ante with the roster of about 80 performers that encompasses everything from marquee names to unique up and comers, and both national and local acts...." -Heather Zimmerman, Silicon Valley Community Newspapers San Jose, CA - June 15, 2011 - San Jose Jazz continues its rich tradition of presenting some of today's most distinguished artists and hottest jazz upstarts at the 22nd San Jose Jazz Summer Fest from Friday, August 12 through Sunday, August 14, 2011 at Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park in downtown San Jose, CA. -

Dur 22/09/2020

MARTES 22 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 2020 3 TÍMPANO BAD BUNNY estrena video musical EFE Más de 10 millones de Miami, Florida personas presenciaron el es- pectáculo a través de Uforia- El artista urbano Bad Live, por televisión en Uni- Bunny estrenó, tras ofrecer visión y la página de YouTu- un concierto que recorrió be de Bad Bunny, según pu- las principales calles de blicó Noah Assad, maneja- Nueva York, el vídeo musi- dor del artista, en su cuenta cal de “Una Vez”, el tema en de Instagram. el que colabora con su com- El concierto arrancó en patriota Mora y que incluyó las afueras del Yankee Sta- en su disco ”Yo Hago Lo dium y recorrió las zonas Que Me Da La Gana”. del Bronx y Washington Hasta el momento, más Heights hasta llegar al Hos- de 1,9 millones de personas pital de Harlem. han visto la pieza audiovi- Durante el recorrido, sual en YouTube dirigida que se demoró más de una por Stillz, un realizador re- hora y media, Bad Bunny currente en los vídeos del interpretó algunos de sus cantante puertorriqueño. grandes éxitos, como “Bye, Mora, por su parte, fue me fui”, “Vete”, “Callaita”, uno de los invitados del “La Romana”, “200 MPH”, mencionado álbum, en el “Ni bien ni mal”, “Te Boté” que también aportó en las y “Yo Perreo Sola”. composiciones de “La Difí- Incluso, durante el tra- cil” y “Soliá”. yecto, decenas de personas “Me vale” es, además, perseguían la plataforma en uno de los temas que Bad la que cantaba Bad Bunny. Bunny interpretó en un La presentación incluyó AGENCIAS concierto que ofreció el do- también las apariciones es- El fundador y curador de adidas Spezial, Gary Aspden, es fanático de New Order, lo que impulsó la asociación. -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

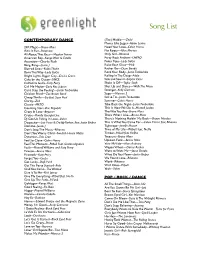

Greenlight's Complete Song List

Song List CONTEMPORARY DANCE (The) Middle—-Zedd Moves Like Jagger--Adam Levine 24K Magic—Bruno Mars Need Your Love--Calvin Harris Ain’t It Fun--Paramore No Roots—Alice Merton All About That Bass—Meghan Trainor Only Girl--Rihanna American Boy--Kanye West & Estelle Party Rock Anthem--LMFAO Attention—Charlie Puth Poker Face--Lady GaGa Bang, Bang—Jessie J Raise Your Glass—Pink Blurred Lines--Robin Thicke Rather Be—Clean Bandit Born This Way--Lady GaGa Rock Your Body--Justin Timberlake Bright Lights, Bigger City--Cee-Lo Green Rolling In The Deep--Adele Cake by the Ocean--DNCE Safe and Sound--Capitol Cities California Gurls--Katy Perry Shake It Off—Taylor Swift Call Me Maybe--Carly Rae Jepson Shut Up and Dance—Walk The Moon Can’t Stop the Feeling!—Justin Timberlake Stronger--Kelly Clarkson Chicken Fried—Zac Brown Band Sugar—Maroon 5 Cheap Thrills—Sia feat. Sean Paul Suit & Tie--Justin Timberlake Clarity--Zed Summer--Calvin Harris Classic--MKTO Take Back the Night--Justin Timberlake Counting Stars-One Republic This Is How We Do It--Montell Jordan Crazy In Love--Beyonce The Way You Are--Bruno Mars Cruise--Florida Georgia Line That’s What I Like—Bruno Mars DJ Got Us Falling In Love--Usher There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back—Shawn Mendes Despacito—Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee, feat. Justin Bieber This Is What You Came For—Calvin Harris feat. Rihanna Domino--Jessie J Tightrope--Janelle Monae Don’t Stop The Music--Rihanna Time of My Life—Pitbull feat. NeYo Don’t You Worry Child--Swedish House Mafia Timber--Pitbull feat. -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries MUSIC The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 24 Etudes by Chopin DVD-4790 Anna Netrebko: The Woman, The Voice DVD-4748 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Piano Trios DVD-6864 25th Anniversary Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Concerts DVD-5528 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Concertos DVD-6865 3 Penny Opera DVD-3329 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Sonatas DVD-6861 3 Tenors DVD-6822 Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: Live in '58 DVD-1598 8 Mile DVD-1639 Art of Conducting: Legendary Conductors of a Golden DVD-7689 Era (PAL) Abduction from the Seraglio (Mei) DVD-1125 Art of Piano: Great Pianists of the 20th Century DVD-2364 Abduction from the Seraglio (Schafer) DVD-1187 Art of the Duo DVD-4240 DVD-1131 Astor Piazzolla: The Next Tango DVD-4471 Abstronic VHS-1350 Atlantic Records: The House that Ahmet Built DVD-3319 Afghan Star DVD-9194 Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp DVD-5189 African Culture: Drumming and Dance DVD-4266 Bach Performance on the Piano by Angela Hewitt DVD-8280 African Guitar DVD-0936 Bach: Violin Concertos DVD-8276 Aida (Domingo) DVD-0600 Badakhshan Ensemble: Song and Dance from the Pamir DVD-2271 Mountains Alim and Fargana Qasimov: Spiritual Music of DVD-2397 Ballad of Ramblin' Jack DVD-4401 Azerbaijan All on a Mardi Gras Day DVD-5447 Barbra Streisand: Television Specials (Discs 1-3) -

Hurricanes and the Forests of Belize, Jon Friesner, 1993. Pdf 218Kb

Hurricanes and the Forests Of Belize Forest Department April 1993 Jon Friesner 1.0 Introduction Belize is situated within the hurricane belt of the tropics. It is periodically subject to hurricanes and tropical storms, particularly during the period June to July (figure 1). This report is presented in three sections. - A list of hurricanes known to have struck Belize. Several lists documenting cyclones passing across Belize have been produced. These have been supplemented where possible from archive material, concentrating on the location and degree of damage as it relates to forestry. - A map of hurricane paths across Belize. This has been produced on the GIS mapping system from data supplied by the National Climatic Data Centre, North Carolina, USA. Some additional sketch maps of hurricane paths were available from archive material. - A general discussion of matters relating to a hurricane prone forest resource. In order to most easily quote sources, and so as not to interfere with the flow of text, references are given as a number in brackets and expanded upon in the reference section. Summary of Hurricanes in Belize This report lists a total of 32 hurricanes. 1.1 On Hurricanes and Cyclones (from C.J.Neumann et al) Any closed circulation, in which the winds rotate anticlockwise in the Northern Hemisphere or clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere, is called a cyclone. Tropical cyclones refer to those circulations which develop over tropical waters, the tropical cyclone basins. The Caribbean Sea is included in the Atlantic tropical cyclone basin, one of six such basins. The others in the Northern Hemisphere are the western North Pacific (where such storms are called Typhoons), the eastern North Pacific and the northern Indian Ocean. -

Santería: from Slavery to Slavery

Santería: From Slavery to Slavery Kent Philpott This, my second essay on Santería, is necessitated for two reasons. One, requests came in for more information about the religion; and two, responses to the first essay indicated strong disagreement with my views. I will admit that my exposure to Santería,1 at that point, was not as thorough as was needed. Now, however, I am relying on a number of books about the religion, all written by decided proponents, plus personal discussions with a broad spectrum of people. In addition, I have had more time to process what I learned about Santería as I interacted with the following sources: (1) Santería the Religion,by Migene Gonzalez-Wippler, (2) Santería: African Spirits in America,by Joseph M. Murphy, (3) Santería: The Beliefs and Rituals of a Growing Religion in America, by Miguel A. De La Torre, (4) Yoruba-Speaking Peoples, by A. B. Ellis, (5) Kingdoms of the Yoruba, 3rd ed., by Robert S. Smith, (6) The Good The Bad and The Beautiful: Discourse about Values in Yoruba Culture, by Barry Hallen, and (7) many articles that came up in a Google search on the term "Santería,” from varying points of view. My title for the essay, "From Slavery to Slavery," did not come easily. I hope to be as accepting and tolerant of other belief systems as I can be. However, the conviction I retained after my research was one I knew would not be appreciated by those who identified with Santería. Santería promises its adherents freedom but succeeds only in bringing them into a kind of spiritual, emotional, and mental bondage that is as devastating as the slavery that originally brought West Africans to the New World in the first place. -

ALAIANDÊ Xirê DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO

ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO ALAIANDÊ XirÊ DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO ALAIANDÊ XIRÊ DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO DOI: 10.11606/9786550130060 ALAIANDÊ XIRÊ DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI São Paulo 2019 Os autores autorizam a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fns de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Universidade de São Paulo Reitor: Vahan Agopyan Vice-reitor: Antonio Carlos Hernandes Faculdade de Educação Diretor: Prof. Dr. Marcos Garcia Neira Vice-Diretor: Prof. Dr. Vinicio de Macedo Santos Direitos desta edição reservados à FEUSP Avenida da Universidade, 308 Cidade Universitária – Butantã 05508-040 – São Paulo – Brasil (11) 3091-2360 e-mail: [email protected] http://www4.fe.usp.br/ Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo A316 Alaiandê Xirê: desafos da cultura religiosa afro-americana no Século XXI / Vagner Gonçalves da Silva, Rosenilton Silva de Oliveira, José Pedro da Silva Neto (Organizadores). São Paulo: FEUSP, 2019. 382 p. Vários autores ISBN: 978-65-5013-006-0 (E-book) DOI: 10.11606/9786550130060 1. Candomblé. 2. Cultura afro. 3. Religião. 4. Religiões africanas. I. Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. II. Oliveira, Rosenilton Silva de. III. Silva Neto, José Pedro. IV. Título. -

Sem. Sem. Pos. Sem. Cert. Actual Ant. Max. Lista Artista Título Sello Promus

GfK - Documento de uso público TOP 100 CANCIONES + STREAMING (Las ventas totales corresponden a los datos enviados por colaboradores habituales de venta física y por los siguientes operadores: Amazon, Google Play Music, i-Tunes, Google Play, Movistar,7Digital, Apple Music, Deezer, Spotify,Napster y Tidal) SEMANA 02: del 04.01.2019 al 10.01.2019 Sem. Sem. Pos. Sem. Cert. Actual Ant. Max. Lista Artista Título Sello Promus. 1 ● 1 1 10 PAULO LONDRA ADAN Y EVA WARNER MUSIC ** 2 ● 2 2 6 6IX9INE / ANUEL AA MALA SCUMGANG RECORDS * 3 ▲ 13 3 6 PEDRO CAPÓ / FARRUKO CALMA SONY MUSIC 4 ▼ 3 1 6 AITANA VAS A QUEDARTE UNIVERSAL ** 5 ▲ 12 5 3 BAD BUNNY NI BIEN NI MAL RIMAS ENTERTAINMENT LLC 6 ▼ 4 4 9 DADDY YANKEE / ANUEL AA ADICTIVA UNIVERSAL ** 7 ▲ 11 7 4 ANUEL AA / HAZE AMANECE HOUSE OF HAZE 8 ▼ 5 1 13 BAD BUNNY / DRAKE MIA WARNER MUSIC 2** 9 ▼ 7 7 10 ANUEL AA / ROMEO SANTOS ELLA QUIERE BEBER REAL HASTA LA MUERTE INC. ** 10 ▼ 6 3 12 C. TANGANA / BECKY G / ALIZZZ BOOTY SONY MUSIC ** 11 ▼ 9 4 12 LUIS FONSI / OZUNA IMPOSIBLE UNIVERSAL ** 12 ▼ 10 10 4 BAD BUNNY SOLO DE MÍ RIMAS MUSIC 13 ▼ 8 1 15 DJ SNAKE / SELENA GOMEZ / OZUNA / CARDI B TAKI TAKI UNIVERSAL 2** 14 ● 14 6 3 LOLA INDIGO / MALA RODRÍGUEZ MUJER BRUJA UNIVERSAL 15 ● 15 2 33 ROSALIA MALAMENTE SONY MUSIC 3** 16 ▲ 24 16 5 CAUTY / RAFA PABON TA TO GUCCI LIMITLESS RECORDS, LLC. 17 ▼ 16 1 24 AITANA TELEFONO UNIVERSAL 3** 18 ▲ 20 8 33 BERET LO SIENTO WARNER MUSIC 2** 19 ▼ 18 12 9 DJ LUIAN / MAMBO KINGZ / ANUEL AA / BECKY G / PRI BUBALU HEAR THIS MUSIC * 20 ▼ 17 1 28 OZUNA / MANUEL TURIZO VAINA LOCA SONY MUSIC 3** 21 ● 21 7 20 OZUNA / ROMEO SANTOS IBIZA SONY MUSIC ** 22 ● 22 13 14 MAIKEL DELACALLE REPLAY UNIVERSAL ** 23 ● 23 12 31 BRYTIAGO / DARELL ASESINA BUSINESS MUSIC 2** 24 ▼ 19 14 15 MARC ANTHONY / WILL SMITH / BAD BUNNY ESTÁ RICO SONY MUSIC ** 25 ▲ 28 10 23 BECKY G / PAULO LONDRA CUANDO TE BESE SONY MUSIC ** 26 ● 26 12 22 MALUMA MALA MÍA SONY MUSIC ** 27 ▲ 35 27 23 C.TANGANA / ROSALIA ANTES DE MORIRME AGORAZEIN 2** 28 ▲ 29 26 8 J.