The Families of Rastan and the Syrian Regime: Transformation and Continuity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Confronting Assad's Anti-Semitism in Germany | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Fikra Forum New Forms of Old Hate: Confronting Assad’s Anti-Semitism in Germany by Rawan Osman Feb 6, 2020 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Rawan Osman Rawan Osman was born in Damascus and raised in Lebanon. After high school, Osman moved back to Syria and in 2011, during the beginning of the unrest, left for France. In 2018, Osman moved to Strasbourg and started working on her first book, "The Israelis, Friends or Foes." Brief Analysis ith this year’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day recognizing the 75th anniversary of the freeing W of Auschwitz, it is also important for the German public to address the potential implications of a new wave of anti-Semitism within its borders. Germany’s notable acceptance of over one million refugees from Syria, where anti-Semitic propaganda has been a key feature of the Assad family’s overall messaging, has both triggered both a rise in Germany’s far-right and brought Germany’s Jewish populations into contact with a new type of anti- Semitism developed as one method of control in the Assad dictatorship. The uncritically anti-Israel and anti-Semitic tropes that have been taught, promoted, or tolerated in Syria pose a new set of challenges to German authorities who are still wrestling with their country’s past. Germany, because of its history, has accepted upon itself a greater responsibility than other European countries to take in refugees. Now it must take on another major responsibility: effectively educating these communities about the Holocaust and the insidious nature of anti-Semitism. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA China, Russia and Iran Seek to Revive Syrian Railways

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA China, Russia and Iran Seek to Revive Syrian Railways OE Watch Commentary: In late November, the Syrian Ministry of Transport announced a major “…China’s ownership of railways lines, in addition to its signing plan to repair, update and expand Syria’s railway of a 2017 agreement with Syria to use the Lattakia Port and system. As detailed in the accompanying excerpt from the Syrian government daily al-Thawra, the maritime transport means that China will own the country…” plan includes completing an earlier project to connect Deir ez-Zor and Albu Kamal, along the border with Iraq’s al-Anbar Province. It also calls for a new line across the Syrian desert, connecting Homs to Deir ez-Zor. Along with helping jump-start the domestic economy, an effective rail network would allow Syria to leverage is strategic location, at the crossroads of historical east-west and north-south trade routes. The accompanying passage from the Syrian opposition news source Enab Baladi highlights the importance of Chinese investment to Syrian reconstruction efforts in general and the railway sector in particular. It cites a Syrian researcher who hints at extensive Chinese involvement in the future ownership of the Syrian rail system, something that, combined with a 2017 agreement allowing China to use the Lattakia Port, means that China will “own the country.” Russia is also involved in revamping the Syrian rail network, and the article notes that Russia’s UralVagonZavod will be providing new railway cars to Syria starting next year. Syria’s planned railroad extension along the Euphrates from Deir ez-Zor to the Iraqi border dates from before the war. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate

SNHR is an independent, non-governmental, nonprofit, human rights organization that was founded in June 2011. SNHR is a Thursday 31 October 2013 certified source for the United Nation in all of its statistics. The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate The documenting party: Syrian Network for Human Rights On Thursday 31 October 2013, about 11:00 pm, a group of “local committees” entered the house of an IDPs family in Al Zara village in Talkalakh city and slaugh- tered a woman and her two children with knives. The location on the map: Alaa Mameesh, the eldest son of the family, told SNHR about the slaughtering of his mother and two brothers at the hands of pro-regime forces Al Shabiha: “The family displaced from Al Zara village due to clashes between Free Army and the regime army which consists of 95% Alawites in that area. The family displaced to Talkalakh city which is controlled by the regime hoping the situation would be better there. When Al Shabiha knew that the building contains people from Al Zara village, they stormed the house and without any investigation they killed them all, my mother, my sister and my brother. My father, Fat-hi Mameesh is an officer in the regime army, he fought the Free Army in many battels. Al Shabiha haven’t asked my family about any information. They killed them only because they are IDPs from Al Zara village which is of a Sunni majority. We couldn’t identify anything about their corpses or whether they buried them or not because they banned anyone from Al Zara village to enter Talkalakh city” 1 www.sn4hr.org - [email protected] The victims’ names: The mother, Elham Jardi/ Homs/ Al Zara village/ (Um Alaa) Hanadi Fat-hi Mameesh, 19-year-old/ Homs/ Al Zara village Mohammad Fat-hi Mameesh, 17-year-old/ Al Zara village. -

Iran and Israel's National Security in the Aftermath of 2003 Regime Change in Iraq

Durham E-Theses IRAN AND ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ ALOTHAIMIN, IBRAHIM,ABDULRAHMAN,I How to cite: ALOTHAIMIN, IBRAHIM,ABDULRAHMAN,I (2012) IRAN AND ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4445/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 . IRAN AND ISRAEL’S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE AFTERMATH OF 2003 REGIME CHANGE IN IRAQ BY: IBRAHIM A. ALOTHAIMIN A thesis submitted to Durham University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DURHAM UNIVERSITY GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS March 2012 1 2 Abstract Following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iran has continued to pose a serious security threat to Israel. -

The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community

STUDY The Alawite Dilemma in Homs Survival, Solidarity and the Making of a Community AZIZ NAKKASH March 2013 n There are many ways of understanding Alawite identity in Syria. Geography and regionalism are critical to an individual’s experience of being Alawite. n The notion of an »Alawite community« identified as such by its own members has increased with the crisis which started in March 2011, and the growth of this self- identification has been the result of or in reaction to the conflict. n Using its security apparatus, the regime has implicated the Alawites of Homs in the conflict through aggressive militarization of the community. n The Alawite community from the Homs area does not perceive itself as being well- connected to the regime, but rather fears for its survival. AZIZ NAKKASH | THE ALAWITE DILEMMA IN HOMS Contents 1. Introduction ...........................................................1 2. Army, Paramilitary Forces, and the Alawite Community in Homs ...............3 2.1 Ambitions and Economic Motivations ......................................3 2.2 Vulnerability and Defending the Regime for the Sake of Survival ..................3 2.3 The Alawite Dilemma ..................................................6 2.4 Regime Militias .......................................................8 2.5 From Popular Committees to Paramilitaries ..................................9 2.6 Shabiha Organization ..................................................9 2.7 Shabiha Talk ........................................................10 2.8 The -

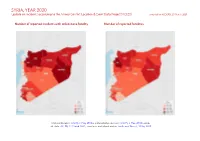

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data.