Assessment of Health Seeking Behavior Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Solukhumbu District, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commercialization of Mandarin Orange in Solukhumbu District, Nepal

K.N. Pant et al. (2019) Int. J. Soc. Sc. Manage. Vol. 6, Issue-4: 97-104 DOI: 10.3126/ijssm.v6i4.26223 Research Article Commercialization of Mandarin Orange in Solukhumbu District, Nepal: Input, Production, Storage and Marketing Problem Assessment Kamal Nayan Pant1*, Dikshit Poudel1, Dipendra Kumar Bamma1, Shovit Khanal1, Madhav Dhital1 Agriculture and Forestry University, Nepal Abstract With the aim to assess major constraints and opportunities in commercialization along with the study of control measures and apposite services provided by stakeholders, the survey among 75 households from 5 different clusters in major citrus producing Dudhkoshi and Thulung Dudhkoshi regions during 2018 was conducted. The result from the pilot study portrays that – despite the long-term farming experiences in citrus, mandarins were unproductive in their orchards. Lack of technical knowledge, input supply, road and market access regarding commercial citrus farming has been major limiting aspect for orchard management and production. Likewise, condition of mechanical tools and record keeping was found poor from direct observation. 49.33% did not have storage facility for the fruit; problem on post-harvest and marketing was followed by poor transportation facility. The market for mandarin was the local market for 34 respondents where the price per kg was NRs. 77.94 which was significantly higher than the farmgate price (NRs. 49.02) at 5% level of significance. The fruit has invincible quality and taste. The development of collection centers, frequent monitoring and trainings for progressive farmers and input supplies management from government and private sectors are suggested, which can promote the productivity of citrus; thus, farming of mandarin can enhance livelihood and can be sustainable venture for the study area. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Damage from the April-May 2015 Gorkha Earthquake Sequence in the Solukhumbu District (Everest Region), Nepal David R

Damage from the april-may 2015 gorkha earthquake sequence in the Solukhumbu district (Everest region), Nepal David R. Lageson, Monique Fort, Roshan Raj Bhattarai, Mary Hubbard To cite this version: David R. Lageson, Monique Fort, Roshan Raj Bhattarai, Mary Hubbard. Damage from the april-may 2015 gorkha earthquake sequence in the Solukhumbu district (Everest region), Nepal. GSA Annual Meeting, Sep 2016, Denver, United States. hal-01373311 HAL Id: hal-01373311 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01373311 Submitted on 28 Sep 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DAMAGE FROM THE APRIL-MAY 2015 GORKHA EARTHQUAKE SEQUENCE IN THE SOLUKHUMBU DISTRICT (EVEREST REGION), NEPAL LAGESON, David R.1, FORT, Monique2, BHATTARAI, Roshan Raj3 and HUBBARD, Mary1, (1)Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, 226 Traphagen Hall, Bozeman, MT 59717, (2)Department of Geography, Université Paris Diderot, 75205 Paris Cedex 13, Paris, France, (3)Department of Geology, Tribhuvan University, Tri-Chandra Campus, Kathmandu, Nepal, [email protected] ABSTRACT: Rapid assessments of landslides Valley profile convexity: Earthquake-triggered mass movements (past & recent): Traditional and new construction methods: Spectrum of structural damage: (including other mass movements of rock, snow and ice) as well as human impacts were conducted by many organizations immediately following the 25 April 2015 M7.8 Gorkha earthquake and its aftershock sequence. -

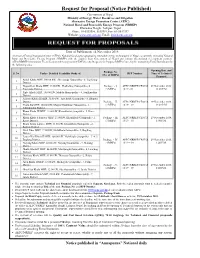

Request for Proposal (Notice Published)

Request for Proposal (Notice Published) Government of Nepal Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) National Rural and Renewable Energy Program (NRREP) Khumaltar Height, Lalitpur, Nepal Phone: 01-5539390, 5539391, Fax: 01-5542397 Website: www.aepc.gov.np, Email: [email protected] Date of Publication: 14 November 2018 Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC): National focal agency promoting renewable energy technologies in Nepal, is currently executing National Rural and Renewable Energy Program (NRREP) with the support from Government of Nepal and various international development partners. AEPC/NRREP/Community Electrification Sub-Component (CESC) hereby Requests for Proposal (RFP) from eligible Consulting Firms/Institutions for the following tasks: Opening Date and Package No. S. No. Tasks - Detailed Feasibility Study of: RFP Number Time of Technical (No. of MHPs) Proposal Aamji Khola MHP, 100.00 kW, Shreejanga Gaunpalika - 8, Taplejung 1 District Nagpokhari Khola MHP, 15.00 kW, Phaktalung Gaunpalika - 6, Package - I, AEPC/NRREP/CESC/20 29 November 2018, 2 Taplejung District (3 MHPs) 18/19 - 01 12.20 P.M. Piple Khola MHP, 100.00 kW, Makalu Municipality - 4, Sankhusabha 3 District Aakuwa Khola II MHP, 32.00 kW, Amchowk Gaunpalika - 8, Bhojpur 4 District Package - II, AEPC/NRREP/CESC/20 29 November 2018, Cholu Ku MHP, 100.00 kW, Mapya Dhudhkosi Gaunpalika - 1, (2 MHPs) 18/19 – 02 12:40 P.M. 5 Solukhumbu District Khani Khola III MHP, 11.00 kW, Khanikhola Gaunpalika - 5, Kavre 6 District Khani Khola Falametar MHP, 23.00 kW, Khanikhola Gaunpalika - 2, Package - III, AEPC/NRREP/CESC/20 29 November 2018, 7 Kavre District (3 MHPs) 18/19 – 03 1:00 P.M. -

Table of Province 01, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census 2018

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Taplejung District 4,653 13,225 7,337 5,888 10101PHAKTANLUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 539 1,178 672 506 10102MIKWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 269 639 419 220 10103MERINGDEN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 397 1,125 623 502 10104MAIWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 310 990 564 426 10105AATHARAI TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 433 1,770 837 933 10106PHUNGLING MUNICIPALITY 1,606 4,832 3,033 1,799 10107PATHIBHARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 398 1,067 475 592 10108SIRIJANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 452 1,064 378 686 10109SIDINGBA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 249 560 336 224 Sankhuwasabha District 6,037 18,913 9,996 8,917 10201BHOTKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 294 989 541 448 10202MAKALU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 437 1,317 666 651 10203SILICHONG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 401 1,255 567 688 10204CHICHILA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 199 586 292 294 10205SABHAPOKHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 220 751 417 334 10206KHANDABARI MUNICIPALITY 1,913 6,024 3,281 2,743 10207PANCHAKHAPAN MUNICIPALITY 590 1,732 970 762 10208CHAINAPUR MUNICIPALITY 1,034 3,204 1,742 1,462 10209MADI MUNICIPALITY 421 1,354 596 758 10210DHARMADEVI MUNICIPALITY 528 1,701 924 777 Solukhumbu District 3,506 10,073 5,175 4,898 10301 KHUMBU PASANGLHAMU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 702 1,906 904 1,002 10302MAHAKULUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 369 985 464 521 10303SOTANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 265 787 421 366 10304DHUDHAKOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 263 802 416 386 10305 THULUNG DHUDHA KOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 456 1,286 652 634 10306NECHA SALYAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 353 1,054 509 545 10307SOLU DHUDHAKUNDA MUNICIPALITY -

Phaplu Airport

PHAPLU AIRPORT Brief Description Phaplu Airport is situated at Solu Dudhkund Municipality of Solukhumbu District, Province No. 1. The airport is in close proximity to District Headquarter, Salleri. This airport is the gateway to Khumbu Trekking Route. General Information Name PHAPLU Location Indicator VNPL IATA Code PPL Aerodrome Reference Code 1B Aerodrome Reference Point 273053 N/0863510 E Province/District 1(One)/Solukhumbu Distance and Direction from City 1 Km North West Elevation 2468 m. /8097 ft. Contact Off: 977-38520153 Tower: 977-38520153 Fax: 977-38520153 AFS: VNPLYDYX E-mail: [email protected] Operation Hours 16th Feb to 15th Nov 0600LT-1215LT 16th Nov to 15th Feb 0630LT-1215LT Status In Operation Year of Start of Operation October, 1976 Serviceability All Weather Land Approx. 84288.04 m2 Re-fueling Facility Not Available Service AFIS Type of Traffic Permitted Visual Flight Rules (VFR) Type of Aircraft D228, DHC6, L410, Y12 Schedule Operating Airlines Tara Air, Sita Air, Nepal Airlines, Summit Air Schedule Connectivity Kathmandu, Lukla RFF Not Available Infrastructure Condition Airside Runway Type of Surface Bituminous Paved (Asphalt Concrete) Runway Dimension 680 m x 20 m Runway Designation 02/20 Parking Capacity Three D228 Types Size of Apron 1600 sq.m. Apron Type Asphalt Concrete Passenger Facilities Hotels Yes (city area) Restaurants Yes Transportations Jeep, Tractor, Van Internet Facility Wi-Fi Cable TV Yes Airport Facilities Console One Man Position Tower Console with Associated Equipment and Accessories Communication, -

Solukhumbu District EOI : DOED/EOI/05/NCB/2075/76/S Office Name: Department of Electricity Development Office Address: Sanogaucharan, Gyaneshwor Kathmandu

EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) Title of Consulting Service: DOED/EOI/05/NCB/2075/76/S Method of Consulting Service: National Project Name : Feasibility and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study of Middle Inkhu Hydropower Project (25.3 MW), Solukhumbu District EOI : DOED/EOI/05/NCB/2075/76/S Office Name: Department of Electricity Development Office Address: Sanogaucharan, Gyaneshwor Kathmandu Funding agency : Government Budget ABBREVIATIONS CV - Curriculum Vitae DoED - Department of Electricity Development EA - Executive Agency EOI - Expression of Interest GON - Government of Nepal MOFE - Ministry of Forest and Environment MoEWRI- Ministry of Energy, Water Resource and Irrigation PAN - Permanent Account Number PPA - Public Procurement Act PPR - Public Procurement Regulation PRoR - Peaking Run-off River RoR - Run-off River TOR - Terms of Reference VAT - Value Added Tax Table of Contents Section I. A. Request for Expression of Interest 4 Section II. B. Instructions for submission of Expression of Interest 6 Section III. C. Objective of Consultancy Services or Brief TOR 8 Section IV. D. Evaluation of Consultant's EOI Application 14 Section V. E. EOI Forms and Formats 17 A. Request for Expression of Interest Request for Expression of Interest Government of Nepal (GoN) Name of Employer: Department of Electricity Development Date: 30-04-2019 05:00 Name of Project: Feasibility and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study of Middle Inkhu Hydropower Project (25.3 MW), Solukhumbu District 1. Government of Nepal (GoN) has allocated fund toward the cost of Feasibility and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study of Middle Inkhu Hydropower Project (25.3 MW), Solukhumbu District and intend to apply portion of this fund to eligible payments under the Contract for which this Expression of Interest is invited for National consulting service 2. -

The Geographical Journal of Nepal Vol 13

Volume 13 March 2020 JOURNAL OF NEPAL THE GEOGRAPHICAL ISSN 0259-0948 (Print) THE GEOGRAPHICAL ISSN 2565-4993 (Online) Volume 13 March 2020 JOURNAL OF NEPAL Changing forest coverage and understanding of deforestation in Nepal Himalayas THE GEOGRAPHICAL Prem Sagar Chapagain and Tor H. Aase Doi: http://doi.org/103126/gjn.v13i0.28133 Selecting tree species for climate change integrated forest restoration and management in the Chitwan- Annapurna Landscape, Nepal JOURNAL OF NEPAL Gokarna Jung Thapa and Eric Wikramanayake Doi: http://doi.org/103126/gjn.v13i0.28150 Evolution of cartographic aggression by India: A study of Limpiadhura to Lipulek Jagat K. Bhusal Doi: http://doi.org/10.3126/gjn.v13i0.28151 Women in foreign employment: Its impact on the left behind family members in Tanahun district, Nepal Kanhaiya Sapkota Doi: http://doi.org/10.3126/gjn.v13i0.28153 Geo-hydrological hazards induced by Gorkha Earthquake 2015: A Case of Pharak area, Everest Region, Nepal Buddhi Raj Shrestha, Narendra Raj Khanal, Joëlle Smadja, Monique Fort Doi: http://doi.org/10.3126/gjn.v13i0.28154 Basin characteristics, river morphology, and process in the Chure-Terai landscape: A case study of the Bakraha river, East Nepal Motilal Ghimire Doi: http://doi.org/10.3126/gjn.v13i0.28155 Pathways and magnitude of change and their drivers of public open space in Pokhara Metropolitan City, Nepal Ramjee Prasad Pokharel and Narendra Raj Khanal Doi: http://doi.org/10.3126/gjn.v13i0.28156 13 March 2020 Volume The Saptakoshi high dam project and its bio-physical consequences -

Garma-Nele-Bogal Road Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub-Project

Initial Environmental Examination Garma-Nele-Bogal Road Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub-project November 2017 NEP: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Prepared by Office of District Level Project Implementation Unit (Solukhumbu)- Central Level Project Implementation Unit – Ministry of Federals Affairs and Local Development for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental Assessment Document Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Garma-Nele-Bogal Road Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub-project November 2017 NEP: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Loan: 3260 Project Number: 49215-001 Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). This Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s -

Medico-Ethnobiology in Rai Community: a Case Study from Baikunthe Village Development Committee, Bhojpur, Eastern Nepal

ISSN: 2469-9062 (print), 2467-9240(e) Journal of Institute of Science and Technology, 2015, 20(1): 127-132, © IOST, Tribhuvan University Medico-ethnobiology in Rai Community: A Case Study from Baikunthe Village Development Committee, Bhojpur, Eastern Nepal Rabina Rai1 and N.B. Singh1, 2 1Central Department of Environmental Science, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu 2Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu 1E-mail: [email protected] and 2E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper tried to explore the uses of medicinal animals and plants for the treatment of different diseases in the Rai community of Baikunthe VDC, Bhojpur, Nepal. About 87 plant species belonging to 55 families were used in treating 65 types of diseases while 27 different animal species belonging to 23 families were used in healing 28 ailments. The community is rich in traditional medicinal knowledge and has been using several plants and animal species for healing ailments in their day to day life. Finally, to protect their knowledge, awareness dissemination and further documentation has become vital. Keywords: Ethnomedicine, Medicinal plants, Rai, Traditional knowledge, Zootherapeutic INTRODUCTION Human beings have strong and intimate linkage with et al. (2004), Siwakoti et al. (2005), Pokhrel (2006), the plants and animals for sustaining life in extreme and Malla and Chhetri (2009), Kunwar and Bussman (2009), critical environment. These connections are seen in every Dangol (2010), Lohani (2010), Lohani (2011), Lohani culture across the world, in multiple forms of interaction (2012), and Singh et al. (2012). with local animals as well as plants (Alves 2011). The The documentation of indigenous use of plants by Rai uses of plants and animals as medicines have passed community seems to begin with the work of Toba (1975) from generation to generation in the form of traditional who documented the names of plants in Khaling (Rai and indigenous knowledge. -

Solukhumbu DDC and Dudhkunda Municipality

Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Office District Development Committee, Solukhumbu and Dudhkunda Municipality Local Governance and Community Development Program II Narrative Report Fiscal Year 2071/072 SUBMITTED BY: SUBMITTED TO: SOLUKHUMBU DDC OFFICE LOCAL GOVERNANCE AND COMMUNITY DUDHKUNDA MUNICIPALITY OFFICE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME SALLERI, SOLUKHUMBU (LGCDP)II REGIONAL COORDINATION UNIT( RCU) HETAUNDA Narrative Report Solukhumbu Page 1 Table of Contents S.No Contents Page No. 1.0 Executive Summary 1-2 2.0 Introduction 3-4 3.0 Output wise Progress Status (Output 1-7) 5-20 4.0 Problems and issues (Output 1-7) 20-22 5.0 ANNEXES 22 ANNEX 1. A) LIVLIHOOD IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM (LIP) 22-24 SOLUKHUMBU DDC OFFICE B) LIVLIHOOD IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM (LIP) 24 DUDHKUNDA MUNICIPALITY ANNEX 2. A) SMALL INFRASRUCTURE PROGRAM (SIP) 25-26 SOLUKHUMBU DDC OFFICE B) SMALL INFRASRUCTURE PROGRAM (SIP) 27 DUDHKUDNA MUNICIPALITY OFFICE ANNEX 3. Success Stories 28-31 ANNEX 4. Details about result based management RBM data 31-40 4. A) Solukhumbu DDC Office Annual RBM Report 4. B) Dudhkunda Municipality Office Annual RBM Report 40-43 ANNEX 5. PFM of infrastructure projects (From Online Reporting) 44 5. A) PFM prepared by DDC 5. A) PFM prepared by Municipality 44-45 ANNEX 6. Details about ICT 45 ANNEX 7: Detail Financial report 10. A) DDC 465-47 10. B) Municipality 47 ANNEX 8. LSP Details with VDC cluster 48 ANNEX 9. Details about Social Mobilisation 49-51 ANNEX 10. Information of social mobilizers 52-53 Narrative Report Solukhumbu Page 2 1. Executive Summary Local Governance and community Development Programme (LGCDP) is a national flagship programme in the area of local governance and community development. -

NEPAL NATIONAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER Standard Operating Procedure Transport and Storage Services December 2020

NEPAL NATIONAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER Standard Operating Procedure Transport and Storage Services December 2020 OVERVIEW This document explains the scope of the logistics services provided by the National Logistics Cluster, in support of the COVID-19 response in Nepal, how humanitarian actors and Nepal Government may access these services, and the conditions under which these services will be provided. The objective of the transport and storage services is to support humanitarian organisations and Government to establish a supply chain of medicines, medical supplies and equipment and humanitarian relief supplies mandated by the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) for Prevention of COVID-19 transmission, control and treatment to the hospitals and primary healthcare facilities. These services are not intended to replace the logistics capacities of responding organisations, nor are they meant to compete with the commercial market. Rather, they are intended to fill identified gaps and provide an option as last resort in case private sector service-providers are limited or unable to provide services due to the lockdown. These services are planned to be available until 28 February 2020, with the possibility of further extension. The services may be withdrawn before this date in part or in full, for any of the following reasons: • Changes in the situation on the ground • No longer an agreed upon/identified gap in transport and storage • Funding constraints The Logistics Cluster in Nepal will provide storage services (non-Cold Chain) for medicines, medical supplies and equipment and humanitarian relief supplies for COVID-19 response at three Humanitarian Staging Areas (HSA's) at Kathmandu Airport, Nepalgunj Airport and Dhangadhi Airport and transport services, provided free-of-cost to the users from Kathmandu to the Provincial capitals and the two provincial HSA's and from the provincial capitals to the district headquarters, as specified below.