The COVID-19 Pandemic Vs Post-Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q30portada EN.Qxp

30 Issue. 30 QUA- January - June 2008 DERNS DEL CAC www.cac.cat Scientific knowledge on audiovisual media Quaderns del CAC issue 30, January - June 2008 Contents E-mail: [email protected] .Introduction 2 Editorial Board: Santiago Ramentol i Massana (editor), Dolors Comas .Monographic: Scientific knowledge on audiovisual d’Argemir i Cendra, Rafael Jorba i Castellví, Elisenda media Malaret i Garcia, Esteve Orriols i Sendra, Josep Pont Ethics and engagement in scientific communication 3 i Sans Milagros Pérez Oliva Science documentaries and their coordinates 11 Director: Bienvenido León Josep Gifreu 2001 odysseys through space-time: (uncon)science 19 in the cinema? Executive Director: Maria Corominas Jordi José Playing at scientists: video games and popularising 27 General Coordinator: science Sylvia Montilla Óliver Pérez, Mercè Oliva, Frederic Guerrero and Fermín Ciaurriz Sections: Internet users are shaking the tree of science 37 Carles Llorens (Book Reviews Editor) Luis Ángel Fernández Hermana Núria Fernández and Pablo Santcovsky The scientific popularisation of environmental problems 43 (Book Review, Journal Review, Website Review) by the media. The case of the documentary An Inconvenient Truth Translation: Nel·lo Pellisser Tracy Byrne Doctors in TV fiction 51 Charo Lacalle Page Layout: Health on the internet: proposals for quality and 61 Yago Díaz certification Miquel Àngel Mayer, José Luis Terrón and Angela Leis Legal diposit book: B-17.999/98 ISSN: 1138-9761 Science and technology on Catalan area television 69 Gemma Revuelta and Marzia Mazzonetto Popularising science and technology on generalist radio 81 Catalan Audiovisual Council Maria Gutiérrez President: Josep Maria Carbonell i Abelló .Observatory Vice president: Domènec Sesmilo i Rius Independent television production in Catalonia 91 Secretary: Santiago Ramentol i Massana in a changing market Members of the Council: Dolors Comas d’Argemir i Cendra, David Fernández Quijada Rafael Jorba i Castellví, Elisenda Malaret i Garcia, Josep New interactive advertising formats on television. -

Annales, Series Historia Et Sociologia 27, 2017, 1

UDK 009 ISSN 1408-5348 Anali za istrske in mediteranske študije Annali di Studi istriani e mediterranei Annals for Istrian and Mediterranean Studies Series Historia et Sociologia, 27, 2017, 1 KOPER 2017 ANNALES · Ser. hist. sociol. · 27 · 2017 · 1 ISSN 1408-5348 UDK 009 Letnik 27, leto 2017, številka 1 UREDNIŠKI ODBOR/ Roderick Bailey (UK), Simona Bergoč, Furio Bianco (IT), Milan COMITATO DI REDAZIONE/ Bufon, Alexander Cherkasov (RUS), Lucija Čok, Lovorka Čoralić BOARD OF EDITORS: (HR), Darko Darovec, Goran Filipi (HR), Devan Jagodic (IT), Vesna Mikolič, Luciano Monzali (IT), Aleksej Kalc, Avgust Lešnik, John Martin (USA), Robert Matijašić (HR), Darja Mihelič, Edward Muir (USA), Vojislav Pavlović (SRB), Peter Pirker (AUT), Claudio Povolo (IT), Andrej Rahten, Vida Rožac Darovec, Mateja Sedmak, Lenart Škof, Marta Verginella, Tomislav Vignjević, Paolo Wulzer (IT), Salvator Žitko Glavni urednik/Redattore capo/ Editor in chief: Darko Darovec Odgovorni urednik/Redattore responsabile/Responsible Editor: Salvator Žitko Uredniki/Redattori/Editors: Urška Lampe, Gorazd Bajc Prevajalci/Traduttori/Translators: Petra Berlot (it.) Oblikovalec/Progetto grafico/ Graphic design: Dušan Podgornik , Darko Darovec Tisk/Stampa/Print: Grafis trade d.o.o. Založnik/Editore/Published by: Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko - Koper / Società storica del Litorale - Capodistria© Za založnika/Per Editore/ Publisher represented by: Salvator Žitko Sedež uredništva/Sede della redazione/ SI-6000 Koper/Capodistria, Garibaldijeva/Via Garibaldi 18, Address of Editorial Board: e-mail: [email protected], internet: http://www.zdjp.si/ Redakcija te številke je bila zaključena 15. 3. 2017. Sofinancirajo/Supporto finanziario/ Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije Financially supported by: (ARRS), Luka Koper, Mestna občina Koper Annales - Series historia et sociologia izhaja štirikrat letno. -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

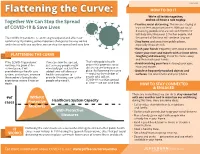

Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’Re All in This Together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and We All Have a Role to Play

3/23/2020 HOW TO DO IT Flattening the Curve: 3/9/2020 We’re all in this together, Together We Can Stop the Spread and we all have a role to play. • Practice social distancing. This means staying at of COVID-19 & Save Lives least six feet away from others. Without social distancing, people who are sick with COVID-19 will likely infect between 2-3 other people, and The COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to expand and affect our the spread of the virus will continue to grow. community. By making some important changes to the way we live • Stay home and away from public places, and interact with one another, we can stop the spread and save lives. especially if you are sick. • Wash your hands frequently with soap and water. • Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when FLATTENING THE CURVE coughing and sneezing, throw the tissue away and then wash your hands. If the COVID-19 pandemic If we can slow the spread, That’s why public health orders that promote social • Avoid touching your face including your eyes, continues to grow at the just as many people might nose and mouth. current pace, it will eventually get sick, but the distancing are being put in overwhelm our health care added time will allow our place. By flattening the curve • Disinfect frequently touched objects and system, and in-turn, increase health care system to — reducing the number of surfaces, like door knobs and your phone. the number of people who provide lifesaving care to the people who will get experience severe illness or people who need it. -

Trump Contracts COVID

MILITARY VIDEO GAMES COLLEGE FOOTBALL National Guard designates Spelunky 2 drops Air Force finally taking units in Alabama, Arizona players into the role the field for its first to respond to civil unrest of intrepid explorer game as it hosts Navy Page 4 Page 14 Back page Report: Nearly 500 service members died by suicide in 2019 » Page 3 Volume 79, No. 120A ©SS 2020 CONTINGENCY EDITION SATURDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2020 stripes.com Free to Deployed Areas Trump contracts COVID White House says president experiencing ‘mild symptoms’ By Jill Colvin and Zeke Miller Trump has spent much of the year downplaying Associated Press the threat of a virus that has killed more than WASHINGTON — The White House said Friday 205,000 Americans. that President Donald Trump was suffering “mild His diagnosis was sure to have a destabilizing symptoms” of COVID-19, making the stunning effect in Washington and around the world, announcement after he returned from an evening raising questions about how far the virus has fundraiser without telling the crowd he had been spread through the highest levels of the U.S. exposed to an aide with the disease that has government. Hours before Trump announced he killed a million people worldwide. had contracted the virus, the White House said The announcement that the president of the a top aide who had traveled with him during the United States and first lady Melania Trump week had tested positive. had tested positive, tweeted by Trump shortly “Tonight, @FLOTUS and I tested positive for after midnight, plunged the country deeper into COVID-19. -

Intentional Disregard: Trump's Authoritarianism During the COVID

INTENTIONAL DISREGARD Trump’s Authoritarianism During the COVID-19 Pandemic August 2020 This report is dedicated to those who have suffered and lost their lives to the COVID-19 virus and to their loved ones. Acknowledgments This report was co-authored by Sylvia Albert, Keshia Morris Desir, Yosef Getachew, Liz Iacobucci, Beth Rotman, Paul S. Ryan and Becky Timmons. The authors thank the 1.5 million Common Cause supporters whose small-dollar donations fund more than 70% of our annual budget for our nonpartisan work strengthening the people’s voice in our democracy. Thank you to the Common Cause National Governing Board for its leadership and support. We also thank Karen Hobert Flynn for guidance and editing, Aaron Scherb for assistance with content, Melissa Brown Levine for copy editing, Kerstin Vogdes Diehn for design, and Scott Blaine Swenson for editing and strategic communications support. This report is complete as of August 5, 2020. ©2020 Common Cause. Printed in-house. CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................ 3 President Trump’s ad-lib pandemic response has undermined government institutions and failed to provide states with critically needed medical supplies. .............5 Divider in Chief: Trump’s Politicization of the Pandemic .................................... 9 Trump has amplified special interest-funded “liberate” protests and other “reopen” efforts, directly contradicting public health guidance. ...................9 Trump and his enablers in the Senate have failed to appropriate adequate funds to safely run this year’s elections. .........................................11 President Trump has attacked voting by mail—the safest, most secure way to cast ballots during the pandemic—for purely personal, partisan advantage. ..............12 The Trump administration has failed to safeguard the health of detained and incarcerated individuals. -

Political Rhetoric and Minority Health: Introducing the Rhetoric- Policy-Health Paradigm

Saint Louis University Journal of Health Law & Policy Volume 12 Issue 1 Public Health Law in the Era of Alternative Facts, Isolationism, and the One Article 7 Percent 2018 Political Rhetoric and Minority Health: Introducing the Rhetoric- Policy-Health Paradigm Kimberly Cogdell Grainger North Carolina Central University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/jhlp Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons Recommended Citation Kimberly C. Grainger, Political Rhetoric and Minority Health: Introducing the Rhetoric-Policy-Health Paradigm, 12 St. Louis U. J. Health L. & Pol'y (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.slu.edu/jhlp/vol12/iss1/7 This Symposium Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint Louis University Journal of Health Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Scholarship Commons. For more information, please contact Susie Lee. SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW POLITICAL RHETORIC AND MINORITY HEALTH: INTRODUCING THE RHETORIC-POLICY-HEALTH PARADIGM KIMBERLY COGDELL GRAINGER* ABSTRACT Rhetoric is a persuasive device that has been studied for centuries by philosophers, thinkers, and teachers. In the political sphere of the Trump era, the bombastic, social media driven dissemination of rhetoric creates the perfect space to increase its effect. Today, there are clear examples of how rhetoric influences policy. This Article explores the link between divisive political rhetoric and policies that negatively affect minority health in the U.S. The rhetoric-policy-health (RPH) paradigm illustrates the connection between rhetoric and health. Existing public health policy research related to Health in All Policies and the social determinants of health combined with rhetorical persuasive tools create the foundation for the paradigm. -

Official Proceedings of the Meetings of the Board Of

OFFICIAL PROCEEDINGS OF THE MEETINGS OF THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF PORTAGE COUNTY, WISCONSIN January 18, 2005 February 15, 2005 March 15, 2005 April 19, 2005 May 17, 2005 June 29, 2005 July 19, 2005 August 16,2005 September 21,2005 October 18, 2005 November 8, 2005 December 20, 2005 O. Philip Idsvoog, Chair Richard Purcell, First Vice-Chair Dwight Stevens, Second Vice-Chair Roger Wrycza, County Clerk ATTACHED IS THE PORTAGE COUNTY BOARD PROCEEDINGS FOR 2005 WHICH INCLUDE MINUTES AND RESOLUTIONS ATTACHMENTS THAT ARE LISTED FOR RESOLUTIONS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE COUNTY CLERK’S OFFICE RESOLUTION NO RESOLUTION TITLE JANUARY 18, 2005 77-2004-2006 ZONING ORDINANCE MAP AMENDMENT, CRUEGER PROPERTY 78-2004-2006 ZONING ORDINANCE MAP AMENDMENT, TURNER PROPERTY 79-2004-2006 HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES NEW POSITION REQUEST FOR 2005-NON TAX LEVY FUNDED-PUBLIC HEALTH PLANNER (ADDITIONAL 20 HOURS/WEEK) 80-2004-2006 DIRECT LEGISLATION REFERENDUM ON CREATING THE OFFICE OF COUNTY EXECUTIVE 81-2004-2006 ADVISORY REFERENDUM QUESTIONS DEALING WITH FULL STATE FUNDING FOR MANDATED STATE PROGRAMS REQUESTED BY WISCONSIN COUNTIES ASSOCIATION 82-2004-2006 SUBCOMMITTEE TO REVIEW AMBULANCE SERVICE AMENDED AGREEMENT ISSUES 83-2004-2006 MANAGEMENT REVIEW PROCESS TO IDENTIFY THE FUTURE DIRECTION TECHNICAL FOR THE MANAGEMENT AND SUPERVISION OF PORTAGE COUNTY AMENDMENT GOVERNMENT 84-2004-2006 FINAL RESOLUTION FEBRUARY 15, 2005 85-2004-2006 ZONING ORDINANCE MAP AMENDMENT, WANTA PROPERTY 86-2004-2006 AUTHORIZING, APPROVING AND RATIFYING A SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT INCLUDING GROUND -

Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown Units in New York State Correctional Facilities

Pace Law Review Volume 24 Issue 2 Spring 2004 Prison Reform Revisited: The Unfinished Article 6 Agenda April 2004 Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown Units in New York State Correctional Facilities Jennifer R. Wynn Alisa Szatrowski Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Recommended Citation Jennifer R. Wynn and Alisa Szatrowski, Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown Units in New York State Correctional Facilities, 24 Pace L. Rev. 497 (2004) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol24/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Modern American Penal System Hidden Prisons: Twenty-Three-Hour Lockdown Units in New York State Correctional Facilities* Jennifer R. Wynnt Alisa Szatrowski* I. Introduction There is increasing awareness today of America's grim in- carceration statistics: Over two million citizens are behind bars, more than in any other country in the world.' Nearly seven mil- lion people are under some form of correctional supervision, in- cluding prison, parole or probation, an increase of more than 265% since 1980.2 At the end of 2002, 1 of every 143 Americans 3 was incarcerated in prison or jail. * This article is based on an adaptation of a report entitled Lockdown New York: Disciplinary Confinement in New York State Prisons, first published by the Correctional Association of New York, in October 2003. -

Pandemic.Pdf.Pdf

1 PANDEMICS: Past, Present, Future Published in 2021 by the Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Challenges & Opportunities Sustainable Development, 35 Ferozshah Road, New Delhi 110001, India © UNESCO MGIEP This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike Coordinating Lead Authors: 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ANANTHA KUMAR DURAIAPPAH by-sa/3.0/ igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be Director, UNESCO MGIEP bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http:// www.unesco.org/openaccess/terms-use-ccbysa-en). KRITI SINGH Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they Lead Authors: NANDINI CHATTERJEE SINGH are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP The publication can be cited as: Duraiappah, A. K., Singh, K., Mochizuki, Y. YOKO MOCHIZUKI (Eds.) (2021). Pandemics: Past, Present and Future Challenges and Opportunities. Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP New Delhi. UNESCO MGIEP. SHAHID JAMEEL Coordinating Lead Authors: Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University Anantha Kumar Duraiappah, Director, UNESCO MGIEP Kriti Singh, Research Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Lead Authors: Nandini Chatterjee Singh, Senior Programme Officer, UNESCO MGIEP Contributing Authors: CHARLES PERRINGS Yoko Mochizuki, Head of Policy, UNESCO MGIEP Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University Shahid Jameel, Director, Trivedi School of Biosciences, Ashoka University W. -

Congressional Record—Senate S924

S924 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE March 1, 2021 unanimous consent that the rules of in the subcommittee and shall not be count- IMPEACHMENT procedure of the Committee on Appro- ed for purposes of determining a quorum. Mr. GRASSLEY. Mr. President, just priations for the 117th Congress be f barely a year ago, I was here making a printed in the RECORD. similar statement. Impeachment is one There being no objection, the mate- TRIBUTE TO CHRISTINA NOLAN of the most solemn matters to come rial was ordered to be printed in the Mr. LEAHY. Mr. President, I would before the Senate, but I worry that it’s RECORD, as follows: like to pay tribute to a great also becoming a common occurrence. SENATE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS Before getting into the merits of this Vermonter, Christina Nolan, a most COMMITTEE RULES—117TH CONGRESS impeachment, it is important to reit- dedicated public servant who has I. MEETINGS erate that January 6 was a sad and served as U.S. attorney for the District tragic day for America. I hope we can The Committee will meet at the call of the of Vermont since November 2017. She Chairman. all agree about that. will be resigning her post at the end of What happened here at the Capitol II. QUORUMS this month, 11 years since she first 1. Reporting a bill. A majority of the mem- was completely inexcusable. It was not joined the U.S. Attorney’s Office, but a demonstration of any of our pro- bers must be present for the reporting of a her work and the strong partnerships bill. -

Tlnitrd ~Tatrs ~Rnatr WASHINGTON, DC 20510

tlnitrd ~tatrs ~rnatr WASHINGTON, DC 20510 May 3, 2019 The Honorable Henry Kerner Special Counsel U.S. Office of Special Counsel 1730 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 Dear Special Counsel Kerner: As you know, the Hatch Act generally prohibits certain categories of political activities for all covered employees. 1 I write today to request your assistance with a review of recent oral statements by Kellyanne Conway, Assistant to the President and Senior Counselor. On April 27, 2019, Ms. Conway made the following statements during an interview on CNN: "You want to revisit this the way Joe Biden wants to revisit, respectfully, because he doesn't want to be held to account for his record or lack thereof. And I found his announcement video to be unfortunate, certainly a missed opportunity. But also just very dark and spooky, in that it's taking us, he doesn't have a vision for the future." The chyron on the bottom of the interview periodically identified Ms. Conway as "Counselor to President Trump."2 On April 30, 2019, Ms. Conway made the following statements in response to a question about infrastructure: "You've got middle-class is booming now despite what Joe Biden says. I don't know exactly what country he's talking about when he says he needs to rebuild the middle class. He also just sounds like someone who wasn't vice president for eight years. He's got this whole list of grievances of what's wrong with the country as if he didn't have, as if he didn't work in this building for eight years ..