Saving the Black Cab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE 1.0 PERSONAL DATA: NAME: Edwin Richard Galea BSc, Dip.Ed, Phd, CMath, FIMA, CEng, FIFireE HOME ADDRESS: TELEPHONE: 6 Papillons Walk (home) +44 (0) 20 8318 7432 Blackheath SE3 9SF (work) +44 (0) 20 8331 8730 United Kingdom (mobile) +44 (0)7958 807 303 EMAIL: WEB ADDRESS: Work: [email protected] http://staffweb.cms.gre.ac.uk/~ge03/ Private: [email protected] PLACE AND DATE OF BIRTH: NATIONALITY: Melbourne Australia, 07/12/57 Dual Citizenship Australia and UK MARITAL STATUS: Married, no children EDUCATION: 1981-84: The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. PhD in Astrophysics: The Mathematical Modelling of Rotating Magnetic Upper Main Sequence Stars 1976-80: Monash University, Melbourne, Australia Dip.Ed. and B.Sc.(Hons) in Science, with a double major in mathematics and physics HII(A) 1970-75: St Albans High School, Melbourne, Australia 2.1 CURRENT POSTS: CAA Professor of Mathematical Modelling, University of Greenwich, (1992 - ) Founding Director, Fire Safety Engineering Group, University of Greenwich, (1992 - ) Vice-Chair International Association of Fire Safety Science (Feb 2014 - ) Visiting Professor, University of Ghent, Belgium (2008 - ) Visiting Professor, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL), Haugesund, Norway, (Nov 2015 - ) Technical Advisor Clevertronics (Australia) (March 2015 - ) Associate Editor, The Aeronautical Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society (Nov 2013 - ) Associate Editor, Safety Science (Feb 2017 - ) Expert to the Grenfell Inquiry (Sept 2017 - ) 2.2 PREVIOUS POSTS: External Examiner, Trinity College Dublin (June 2013 – Feb 2017) Visiting Professor, Institut Supérieur des Matériaux et Mécaniques Avancés (ISMANS), Le Mans, France (2010 - 2016) Associate Editor of Fire Science Reviews until it merged with another fire journal (2013 – DOC REF: GALEA_CV/ERG/1/0618/REV 1.0 1 2017) Associate Editor of the Journal of Fire Protection Engineering until it merged with another fire journal (2008 – 2013) 3.0 QUALIFICATIONS: DEGREES /DIPLOMAS Ph.D. -

1 Decision of the Election Committee on a Due Impartiality Complaint Brought by the Respect Party in Relation to the London Deba

Decision of the Election Committee on a due impartiality complaint brought by the Respect Party in relation to The London Debate ITV London, 5 April 2016 LBC 97.3 , 5 April 2016 1. On Friday 29 April 2016, Ofcom’s Election Committee (“the Committee”)1 met to consider and adjudicate on a complaint made by the Respect Party in relation to its candidate for the London Mayoral election, George Galloway (“the Complaint”). The Complaint was about the programme The London Debate, broadcast in ITV’s London region on ITV, and on ITV HD and ITV+1 at 18:00 on Tuesday 5 April 2016 (“the Programme”). The Programme was broadcast simultaneously by LBC on the local analogue radio station LBC 97.3, as well as nationally on DAB radio and on digital television (as a radio channel). 2. The Committee consisted of the following members: Nick Pollard (Chair, Member of the Ofcom Content Board); Dame Lynne Brindley DBE (Member of the Ofcom Board and Content Board); Janey Walker (Member of the Ofcom Content Board); and Tony Close (Ofcom Director with responsibility for Content Standards, Licensing and Enforcement and Member of the Ofcom Content Board). 3. For the reasons set out in this decision, having considered all of the submissions and evidence before it under the relevant provisions of the Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), the Committee decided not to uphold the Respect Party’s complaint. The Committee found that in respect of ITV the broadcast of the Programme complied with the requirements of the Code. In the case of LBC, the Programme did not a contain list of candidates in the 2016 London Mayoral election (in audio form) and LBC therefore breached Rule 6.11. -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

The Allied Occupation of Germany Began 58

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Abdullah, A.D. (2011). The Iraqi Media Under the American Occupation: 2003 - 2008. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/11890/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CITY UNIVERSITY Department of Journalism D Journalism The Iraqi Media Under the American Occupation: 2003 - 2008 By Abdulrahman Dheyab Abdullah Submitted 2011 Contents Acknowledgments 7 Abstract 8 Scope of Study 10 Aims and Objectives 13 The Rationale 14 Research Questions 15 Methodology 15 Field Work 21 1. Chapter One: The American Psychological War on Iraq. 23 1.1. The Alliance’s Representation of Saddam as an 24 International Threat. 1.2. The Technique of Embedding Journalists. 26 1.3. The Use of Media as an Instrument of War. -

Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons from British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2015 Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, Taming the "Feral Beast": Cautionary Lessons From British Press Reform, 55 Santa Clara L. Rev. 323 (2015). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAMING THE "FERAL BEAST"1 : CAUTIONARY LESSONS FROM BRITISH PRESS REFORM Lili Levi* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introdu ction ............................................................................ 324 I. British Press Reform, in Context ....................................... 328 A. Overview of the British Press Sector .................... 328 B. The British Approach to Newspaper Regulation.. 330 C. Phone-Hacking and the Leveson Inquiry Into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press ..... 331 D. Where Things Stand Now ...................................... 337 1. The Royal Charter ............................................. 339 2. IPSO and IM -

Islamic Relief Charity / Extremism / Terror

Islamic Relief Charity / Extremism / Terror meforum.org Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 From Birmingham to Cairo �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Origins ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Branches and Officials ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Government Support ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 17 Terror Finance ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20 Hate Speech ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 25 Charity, Extremism & Terror ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 29 What Now? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 Executive Summary What is Islamic Relief? Islamic Relief is one of the largest Islamic charities in the world. Founded in 1984, Islamic Relief today maintains -

The Development of the UK Television News Industry 1982 - 1998

-iì~ '1,,J C.12 The Development of the UK Television News Industry 1982 - 1998 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alison Preston Deparent of Film and Media Studies University of Stirling July 1999 Abstract This thesis examines and assesses the development of the UK television news industry during the period 1982-1998. Its aim is to ascertain the degree to which a market for television news has developed, how such a market operates, and how it coexists with the 'public service' goals of news provision. A major purpose of the research is to investigate whether 'the market' and 'public service' requirements have to be the conceptual polarities they are commonly supposed to be in much media academic analysis of the television news genre. It has conducted such an analysis through an examination of the development strategies ofthe major news organisations of the BBC, ITN and Sky News, and an assessment of the changes that have taken place to the structure of the news industry as a whole. It places these developments within the determining contexts of Government economic policy and broadcasting regulation. The research method employed was primarily that of the in-depth interview with television news management, politicians and regulators: in other words, those instrumental in directing the strategic development within the television news industry. Its main findings are that there has indeed been a development of market activity within the television news industry, but that the amount of this activity has been limited by the particular economic attributes of the television news product. -

Over to You Mr Johnson Timothy Whitton

Over to you Mr Johnson Timothy Whitton To cite this version: Timothy Whitton. Over to you Mr Johnson. Observatoire de la société britannique, La Garde : UFR Lettres et sciences humaines, Université du Sud Toulon Var, 2011, Londres : capitale internationale, multiculturelle et olympique, 11, pp. 123-145. hal-01923775 HAL Id: hal-01923775 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01923775 Submitted on 15 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Over to you Mr Johnson Timothy WHITTON Résumé In 2008, Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson defeated Ken Livingstone in the third elections to become the executive mayor of London. Livingstone had held this post for the previous eight years during which he had implemented his personal brand of municipal politics and given London back the voice that the city had lost in 1986 when Mrs Thatcher abolished the Greater London Council. It was thought that he would have no credible opponent in 2008 but observers underestimated the potential of “Boris” who was able to oppose “Ken” on his own turf, that of personalising the election almost ad nauseam to the extent that his slogan “Time for a Change” rang particularly true. -

Defining Islamophobia

Defining Islamophobia A Policy Exchange Research Note Sir John Jenkins KCMG LVO Foreword by Trevor Phillips OBE 2 – Defining Islamophobia About the Author Sir John Jenkins spent a 35-year career in the British Diplomatic Service. He holds a BA (Double First Class Honours) and a Ph.D from Jesus College, Cambridge. He also studied at The School of Oriental and African Studies in London (Arabic and Burmese) and through the FCO with the London and Ashridge Business Schools. He is an alumnus of the Salzburg Seminar. He joined the FCO in 1980 and served in Abu Dhabi (1983-86), Malaysia (1989-92) and Kuwait (1995-98) before being appointed Ambassador to Burma (1999- 2002). He was subsequently HM Consul-General, Jerusalem (2003-06), Ambassador to Syria (2006-07), FCO Director for the Middle East and North Africa (2007-09), Ambassador to Iraq (2009-11), Special Representative to the National Transitional Council and subsequently Ambassador to Libya (2011) and Ambassador to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2012-2015). He took an active part in Sir John Chilcott’s Iraq Inquiry and was asked by the Prime Minister in March 2014 to lead a Policy Review into the Muslim Brotherhood. Until his departure from the FCO he was the government’s senior diplomatic Arabist. Trevor Phillips OBE is a writer, broadcaster and businessman. He is the Chairman of Index on Censorship, the international campaign group for freedom of expression, and was chair of both the Equality and Human Rights Commission and the Runnymede Trust. Policy Exchange Policy Exchange is the UK’s leading think tank. -

Print Digital Tv & Radio Sunday Print

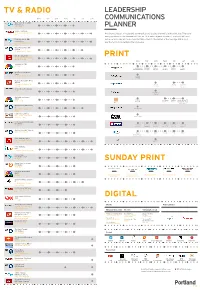

TV & RADIO LEADERSHIP MON TUE WED THUR FRI SAT SUN COMMUNICATIONS Wake Up to Money, BBC Radio 5 Live 5:15 - 6 am PLANNER Sunrise, Sky News 6 - 9 am; Sat & Sun: 6 - 10 One important part of leadership communications is using the media in the right way. There are am many opportunities to communicate live on TV or radio, in print or online. Each has a different 5 Live Breakfast, BBC audience and some will be more suited than others to the leader or the message. But a good Radio 5 Live 6 - 10 am; Sat & Sun 6 - 9 way to start is to understand the landscape. am Today Programme, BBC Radio 4 6 - 9 am; Sat: 7 - 9 am BBC Breakfast, BBC 1 PRINT 6 - 9:15 am ; Sat: 6 - 10 am, Sun: 6 - 7:40 am MON TUE WED THUR FRI SAT SUN Squawkbox, CNBC 6 - 9 am Monday Manifesto; Business Business Business Business Business Business Big Shot Big Shot Big Shot Big Shot Big Shot Big Shot Nick Ferrari Show, LBC Radio 7 - 10 am; Sat: 5 - 7 am Monday Interview Business Daily, BBC World Service 7:32 am; 14.06 pm & Fri Society Friday Saturday 7.32 am Interview Interview Interview (varies) On the Move, Bloomberg 9 am The Business Interview Worldwide Exchange, CNBC Monday 9 am - 11 pm Recruitment Business Lunch with the FT; Interview Interview Speak Person in the News; My Weekend Woman’s Hour, BBC Radio 4 Mon - Fri: 10 - 11 am; Sat: Monday View 4-5pm Daily Politics, BBC 2 Mon - Fri: 12 - 1 pm; Wed: Growth Capital 11:30 am - 1 pm In The Loop with Betty Liu, Bloomberg 1 - 3pm 60 Second 60 Second 60 Second 60 Second 60 Second 60 Second Interview Interview Interview Interview Interview -

Why-Me Final Accounts V.6 Final 13.5.11

COMPANY REGISTRATION NUMBER 06992709 WHY ME? UK COMPANY LIMITED BY GUARANTEE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31 AUGUST 2010 Charity Number 1137123 WHY ME? UK COMPANY LIMITED BY GUARANTEE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS PERIOD ENDED 31 AUGUST 2010 CONTENTS PAGE Trustees Annual Report 3 Independent examiner's report to the members 8 Statement of financial activities (incorporating the income and expenditure account) 9 Balance sheet 10 Notes to the financial statements 11 WHY ME? UK COMPANY LIMITED BY GUARANTEE TRUSTEES ANNUAL REPORT (continued) PERIOD ENDED 31 AUGUST 2010 The trustees, who are also directors for the purposes of company law, have pleasure in presenting their report and the unaudited financial statements of the charity for the period ended 31 August 2010. REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS Registered charity name Why me? UK Charity registration number 1137123 Company registration number 06992709 49-51 East Road Old Street London N1 6AH Registered office 9 Canonbury Square London N1 2AU THE TRUSTEES The trustees who served the charity during the period were as follows: Mr W Riley Sir Charles Pollard Mrs A McHardy STRUCTURE, GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT Why me? UK Ltd is a company limited by guarantee as defined by the Companies Act 2006, and also a registered charity. The Trustees, who were also the directors for the purpose of the company law, and who served during the year were: Mr William F Riley Sir Charles Pollard Mrs Anne McHardy In 2008 Will Riley founded Why me?. As founding Chair, Will invited Sir Charles Pollard QPM to be the first Vice-Chair. He recognised Sir Charles as being a key champion of restorative justice, with valuable knowledge and expertise, who had been closely associated with the Restorative Justice Consortium which initially acted as organisational sponsor. -

Policing the Beats: the Criminalisation of UK Drill and Grime Music by The

SOR0010.1177/0038026119842480The Sociological ReviewFatsis 842480research-article2019 The Sociological Article Review The Sociological Review 2019, Vol. 67(6) 1300 –1316 Policing the beats: The © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: criminalisation of UK drill and sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119842480 10.1177/0038026119842480 grime music by the London journals.sagepub.com/home/sor Metropolitan Police Lambros Fatsis School of Economic, Social and Political Sciences, The University of Southampton, UK Abstract As debates on the rise of violent crime in London unfold, UK drill music is routinely accused of encouraging criminal behaviour among young Black Britons from deprived areas of the capital. Following a series of bans against drill music videos and the imposition of Criminal Behaviour Orders and gang injunctions against drill artists, discussions on the defensibility of such measures call for urgent, yet hitherto absent, sociological reflections on a topical issue. This article attempts to fill this gap, by demonstrating how UK drill and earlier Black music genres, like grime, have been criminalised and policed in ways that question the legitimacy of and reveal the discriminatory nature of policing young Black people by the London Metropolitan Police as the coercive arm of the British state. Drawing on the concept of racial neoliberalism, the policing of drill will be approached theoretically as an expression of the discriminatory politics that neoliberal economics facilitates in order to exclude those who the state deems undesirable or undeserving of its protection. Keywords drill music, grime, policing of Black music subcultures, police racism, race and crime, racial neoliberalism In an atmosphere of rolling news stories about the ‘knife-crime epidemic’ that sweeps the UK’s capital (Channel 4 News, 2018; Lyness & Powell, 2018), drill music has emerged as the ‘soundtrack to London’s murders’ (Knight, 2018) and even blamed for ‘London’s wave of violent crime’ (Beaumont-Thomas, 2018).