Over to You Mr Johnson Timothy Whitton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE 1.0 PERSONAL DATA: NAME: Edwin Richard Galea BSc, Dip.Ed, Phd, CMath, FIMA, CEng, FIFireE HOME ADDRESS: TELEPHONE: 6 Papillons Walk (home) +44 (0) 20 8318 7432 Blackheath SE3 9SF (work) +44 (0) 20 8331 8730 United Kingdom (mobile) +44 (0)7958 807 303 EMAIL: WEB ADDRESS: Work: [email protected] http://staffweb.cms.gre.ac.uk/~ge03/ Private: [email protected] PLACE AND DATE OF BIRTH: NATIONALITY: Melbourne Australia, 07/12/57 Dual Citizenship Australia and UK MARITAL STATUS: Married, no children EDUCATION: 1981-84: The University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. PhD in Astrophysics: The Mathematical Modelling of Rotating Magnetic Upper Main Sequence Stars 1976-80: Monash University, Melbourne, Australia Dip.Ed. and B.Sc.(Hons) in Science, with a double major in mathematics and physics HII(A) 1970-75: St Albans High School, Melbourne, Australia 2.1 CURRENT POSTS: CAA Professor of Mathematical Modelling, University of Greenwich, (1992 - ) Founding Director, Fire Safety Engineering Group, University of Greenwich, (1992 - ) Vice-Chair International Association of Fire Safety Science (Feb 2014 - ) Visiting Professor, University of Ghent, Belgium (2008 - ) Visiting Professor, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences (HVL), Haugesund, Norway, (Nov 2015 - ) Technical Advisor Clevertronics (Australia) (March 2015 - ) Associate Editor, The Aeronautical Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society (Nov 2013 - ) Associate Editor, Safety Science (Feb 2017 - ) Expert to the Grenfell Inquiry (Sept 2017 - ) 2.2 PREVIOUS POSTS: External Examiner, Trinity College Dublin (June 2013 – Feb 2017) Visiting Professor, Institut Supérieur des Matériaux et Mécaniques Avancés (ISMANS), Le Mans, France (2010 - 2016) Associate Editor of Fire Science Reviews until it merged with another fire journal (2013 – DOC REF: GALEA_CV/ERG/1/0618/REV 1.0 1 2017) Associate Editor of the Journal of Fire Protection Engineering until it merged with another fire journal (2008 – 2013) 3.0 QUALIFICATIONS: DEGREES /DIPLOMAS Ph.D. -

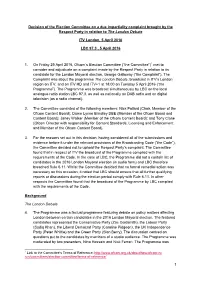

1 Decision of the Election Committee on a Due Impartiality Complaint Brought by the Respect Party in Relation to the London Deba

Decision of the Election Committee on a due impartiality complaint brought by the Respect Party in relation to The London Debate ITV London, 5 April 2016 LBC 97.3 , 5 April 2016 1. On Friday 29 April 2016, Ofcom’s Election Committee (“the Committee”)1 met to consider and adjudicate on a complaint made by the Respect Party in relation to its candidate for the London Mayoral election, George Galloway (“the Complaint”). The Complaint was about the programme The London Debate, broadcast in ITV’s London region on ITV, and on ITV HD and ITV+1 at 18:00 on Tuesday 5 April 2016 (“the Programme”). The Programme was broadcast simultaneously by LBC on the local analogue radio station LBC 97.3, as well as nationally on DAB radio and on digital television (as a radio channel). 2. The Committee consisted of the following members: Nick Pollard (Chair, Member of the Ofcom Content Board); Dame Lynne Brindley DBE (Member of the Ofcom Board and Content Board); Janey Walker (Member of the Ofcom Content Board); and Tony Close (Ofcom Director with responsibility for Content Standards, Licensing and Enforcement and Member of the Ofcom Content Board). 3. For the reasons set out in this decision, having considered all of the submissions and evidence before it under the relevant provisions of the Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), the Committee decided not to uphold the Respect Party’s complaint. The Committee found that in respect of ITV the broadcast of the Programme complied with the requirements of the Code. In the case of LBC, the Programme did not a contain list of candidates in the 2016 London Mayoral election (in audio form) and LBC therefore breached Rule 6.11. -

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Runmed March 2001 Bulletin

No. 325 MARCH Bulletin 2001 RUNNYMEDE’S QUARTERLY Challenge and Change Since the release of our Commission’s report, The Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain, Runnymede has been living in interesting times. Substantial and ongoing media coverage – from the enlivening to the repellent – has fueled the debate.Though the press has focused on some issues at the expense of others, numerous events organised to broaden the discussion continue to explore the Report’s substantial content, and international interest has been awakened. At such a moment, it is a great external organisations wishing to on cultural diversity in the honour for me to be taking over the arrange events. workplace, Moving on up? Racial Michelynn Directorship of Runnymede.The 3. A National Conference to Equality and the Corporate Agenda, a Laflèche, Director of the challenges for the next three years mark the first anniversary of the Study of FTSE-100 Companies,in Runnymede Trust are a stimulus for me and our Report’s launch is being arranged for collaboration with Schneider~Ross. exceptional team, and I am facing the final quarter of 2001, in which This publication continues to be in them with enthusiasm and optimism. we will review the responses to the high demand and follow-up work to Runnymede’s work programme Report over its first year. A new that programme is now in already reflects the key issues and element will be introduced at this development for launching in 2001. recommendations raised in the stage – how to move the debate Another key programme for Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain Report, beyond the United Kingdom to the Runnymede is our coverage of for which a full dissemination level of the European Union. -

Children's 76

CHILDREN'S 76 this Committee agree to make provision in revenue estimates for continuing, on a proportionate basis, the financial aid at present being afforded by Middlesex County Council to the extent shown hereunder to the Voluntary Organisations respectively named, viz.: — £ The Middlesex Association for the Blind ... ... 150 approx. The Southern Regional Association for the Blind ... 49 approx. Middlesex and Surrey League for the Hard of Hearing ... 150 approx. 27. Appointment of Deputy Welfare Officer: RESOLVED: That the Com mittee note the appointment by the Establishment Committee (Appointments Sub-Committee) on 16th November, 1964, of Mr. Henry James Vagg to this post (Scales A/B). (The meeting dosed at 9.10 p.m.) c Chairman. CHILDREN'S COMMITTEE: 30th December, 1964. Present: Councillors Mrs. Nott Cock (in the Chair), Cohen, G. Da vies, Mrs. Edwards, Mrs. Haslam, Mrs. Rees, Rouse, Tackley and B. C. A. Turner. PART I.—RECOMMENDATIONS.—NIL. PART n.—MINUTES. 10. Minutes: RESOLVED: That the minutes of the meeting of the Committee held on 30th September, 1964, having been circulated, be taken as read and signed as a correct record. 11. Appointment of Children's Officer: RESOLVED: That the Committee re ceive the report of the Town Clerk that the London Borough of Harrow Appointments Sub-Committee on 16th November, 1964, appointed Miss C. L. J. S. Boag, at present Area Children's Officer Middlesex County Coun cil, to the post of Children's Officer in the Department of the Medical Officer of Health with effect from 1st April, 1965, at a salary in accordance with lettered Grades C/D. -

Revue Française De Civilisation Britannique, XV-4 | 2010 All ‘Kens’ to All Men

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XV-4 | 2010 Présentations, re-présentations, représentations All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, from the GLC to the GLA À chacun son « Ken ». Ken le caméléon: réinvention et représentation, du Greater London Council à la Greater London Authority Timothy Whitton Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/6151 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2010 ISSN: 0248-9015 Electronic reference Timothy Whitton, “All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, from the GLC to the GLA”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XV-4 | 2010, Online since 01 June 2010, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/6151 This text was automatically generated on 7 January 2021. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, fro... 1 All ‘Kens’ to all Men. Ken the Chameleon: reinvention and representation, from the GLC to the GLA À chacun son « Ken ». Ken le caméléon: réinvention et représentation, du Greater London Council à la Greater London Authority Timothy Whitton 1 Ken Livingstone’s last two official biographies speak volumes about the sort of politician he comes across as being. John Carvel’s title1 is slightly ambiguous and can be interpreted in a variety of ways: Turn Again Livingstone suggests that the one time leader of the Greater London Council (GLC) and twice elected mayor of London shows great skill in steering himself out of any tight corners he gets trapped in. -

Local Government in London Had Always Been More Overtly Partisan Than in Other Parts of the Country but Now Things Became Much Worse

Part 2 The evolution of London Local Government For more than two centuries the practicalities of making effective governance arrangements for London have challenged Government and Parliament because of both the scale of the metropolis and the distinctive character, history and interests of the communities that make up the capital city. From its origins in the middle ages, the City of London enjoyed effective local government arrangements based on the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London and the famous livery companies and guilds of London’s merchants. The essential problem was that these capable governance arrangements were limited to the boundaries of the City of London – the historic square mile. Outside the City, local government was based on the Justices of the Peace and local vestries, analogous to parish or church boundaries. While some of these vestries in what had become central London carried out extensive local authority functions, the framework was not capable of governing a large city facing huge transport, housing and social challenges. The City accounted for less than a sixth of the total population of London in 1801 and less than a twentieth in 1851. The Corporation of London was adamant that it neither wanted to widen its boundaries to include the growing communities created by London’s expansion nor allow itself to be subsumed into a London-wide local authority created by an Act of Parliament. This, in many respects, is the heart of London’s governance challenge. The metropolis is too big to be managed by one authority, and local communities are adamant that they want their own local government arrangements for their part of London. -

Is It Unity They Want, Or Capitulation? by Steve Bakke December 18, 2020

If you don’t regularly receive my reports, request a free subscription at [email protected] ! Follow me on Twitter at http://twitter.com/@BakkeSteve and receive links to my posts and more! Visit my website at http://www.myslantonthings.com ! Is it unity they want, or capitulation? By Steve Bakke December 18, 2020 “It’s time to put the anger and harsh rhetoric behind us and come together as a nation……I pledge to be a president who seeks not to divide but unify……to unite us here at home.” That’s Joe Biden proclaiming unity soon after election day. I’ll again express my concern that this was probably more of a warning than a peace offering. Before I conclude on that speculation let’s look at what others of his flock have been saying lately. Are they friendly and inviting? Do they feel warm and fuzzy? Most quotes are from after election day. Hold on to your seat! • ‘We don’t do things like those chumps out there with the microphones, those Trump guys.” – Joe Biden himself speaking at a small gathering of supporters. • “Hang your head in shame.” – CNN’s Don Lemon addressing republican legislators who supported Trump’s efforts to get the Supreme Court to review constitutional issues regarding the election. • “It’s not enough to just send Donald Trump packing, or even just to repair the damage he’s done. We’ve got to unrig and rebuild the systems that made his rise possible…” – Elizabeth Warren. • ‘I used to wonder how could the people of Germany allow Hitler to exist. -

Seven Dials Guidelines

Conservation area statement Seven Dials (Covent Garden) 7 Newman Street Street Queen Great akrStreet Parker Theatre London tklyStreet Stukeley New aki Street Macklin Drury Lane This way up for map etro Street Betterton Endell St hrsGardens Shorts Neal Street Theatre Cambridge ala Street Earlham Mercer Street omuhStreet Monmouth Dials page 3 Location Seven page 6 History page 10 Character page 19 Audit Tower Street page 26 Guidelines West Street hfebr Avenue Shaftesbury SEVEN DIALS (Covent Garden) Conservation Area Statement The aim of this Statement is to provide a clear indication of the Council’s approach to the preservation and enhancement of the Seven Dials (Covent Garden) Conservation Area. The Statement is for the use of local residents, community groups, businesses, property owners, architects and developers as an aid to the formulation and design of development proposals and change in the area. The Statement will be used by the Council in the assessment of all development proposals. Camden has a duty under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 to designate as conservation areas any “areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or historic interest of which it is desirable to preserve.” Designation provides the basis for policies designed to preserve or enhance the special interest of such an area. Designation also introduces a general control over the demolition of unlisted buildings. The Council’s policies and guidance for conservation areas are contained in the Unitary Development Plan (UDP) and Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG). This Statement is part of SPG and gives additional detailed guidance in support of UDP policies. -

London's Turning the 'London Effect' Threatens to Undermine Labour's Performance at the Next Election

London's Turning The 'London effect' threatens to undermine Labour's performance at the next election. Chris Hamnett argues that it is mainly caused by the vast demographic changes that have taken place in the capital over the last 20 years. Desirable residence: Gentrification changes the political structure of the capital he May 1990 local govern- and Westminster may reflect satisfac- of 1983. In the 1987 general election, for ment elections saw major tion with the lowest poll taxes in Britain example, Labour's vote rose by only gains for Labour across the (£148 and £195 respectively), combined 1.7% in London compared to 3.2% country. There was a national with a fear that Labour control might nationally and Labour lost the inner- Tswing of 11% to Labour compared with lead to an increase. The Tory gains in London constituencies of Fulham and the 1987 general election. But in London Brent and Ealing are partly explicable Battersea following the previous losses the gains were much less - 4% to 5%. in terms of previous Labour policies. of Woolwich, Dulwich, Greenwich and Not only did the Tories strengthen their Labour raised domestic rates by 63% in Bermondsey. control of the flagship boroughs of Ealing in 1987 and staggered from one It has been common to blame the Lon- Westminster and Wandsworth, they political crisis to another in Brent. don 'Loony Left' for this sequence of also wrested control of Ealing from La- But the low swing to Labour in London defeats and there is no doubt that the bour and gained large numbers of seats was not just a feature of the 1990 elec- image of the Left in London has gen- in the inner boroughs of Hammersmith tions. -

1 Rebels As Local Leaders?

Rebels as local leaders? The Mayoralties of Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson Compared Ben Worthy Mark Bennister The Mayoralty of London offers a powerful electoral platform but weak powers to lead a city regarded as ‘ungovernable’ (Travers 2004). This paper adapts the criteria of Hambleton and Sweeting (2004) to look at the first two Mayors’ mandate and vision, style of leadership and policies. Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson were both party rebels, mavericks and skilled media operators. However, their differences are key. As mayor, Livingstone had a powerful vision that translated into a set of clear policy aims while Johnson had a weaker more cautious approach shaped by his desire for higher office. Livingstone built coalitions but proved divisive whereas Johnson was remarkably popular. While Livingstone bought experience and skill, Johnson delegated detail to others. Both their mayoralties courted controversy and faced charges of corruption and cronyism. Both mayors used publicity to make up for weak powers. They also found themselves pushed by their powers towards transport and planning while struggling with deeper issues such as housing. In policy terms Livingstone pushed ahead with the radical congestion charge and a series of symbolic policies. Johnson was far more modest, championing cycling and revelling in the 2012 Olympics while avoiding difficult decisions. The two mayors used their office to negotiate but also challenge central government. Livingstone’s Mayoralty was a platform for personalised change-Johnson’s one for personal ambition. Directly Elected Mayors were introduced to provide local leadership, accountability and vision to UK local government. Beginning under New Labour and continued under the Coalition and Conservatives, directly elected mayors were offered initially by referendum, and later imposed, up and down the country beginning with London 2000 and then in 16 cities and towns including Bristol and Liverpool. -

Docklands Revitalisation of the Waterfront

Docklands Revitalisation of the Waterfront 1. Introduction 2. The beginning of Docklands 2.1. London’s first port 2.2. The medieval port 2.3. London’s Port trough the ages 3. The end of the harbour 4. The Revitalisation 4.1. Development of a new quarter 4.2. New Infrastructure 5. The result 6. Criticism 7. Sources 1. Introduction Docklands is the semi-official name for an area in east London. It is composed of parts of the boroughs of Southwark, Tower Hamlets, Newham and Greenwich. Docklands is named after docks of the London port which had been in this area for centuries. Between 1960 and 1980, all of London's docks were closed, because of the invention of the container system of cargo transportation. For this system the docks were too small. Consequently London had a big area of derelict land which should be used on new way. The solution was to build up a new quarter with flats, offices and shopping malls. Map with 4 the parts of London Docklands and surrounding boroughs (Source: Wikipedia.org) 2. The beginning of Docklands 2.1. London’s first port Within the Roman Empire which stretched from northern Africa to Scotland and from Spain to Turkey, Londinium (London) became an important centre of communication, administration and redistribution. The most goods and people that came to Britain passed through Londinium. Soon this harbour became the busiest place of whole Londinium. On the river a harbour developed were the ships from the west countries and ships from overseas met. 2.2. The medieval port From 1398 the mayor of London was responsible for conserving the river Thames.