Child Growth Curves in High-Altitude Ladakh: Results from a Cohort Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

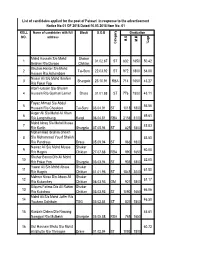

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

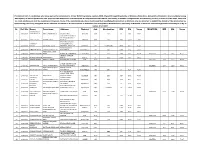

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

Social Welfare Deptt

AADHAR BASED BIOMETRIC IDENTIFICATION AND SKILL PROFILING Reports Select Department :- SOCIAL WELFARE DE Select District :- All Sno. District Name Parentage Address Present Office DOB Category YASMEENA MOHD ANWAR DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 1 ANANTNAG FOHAR MATTAN ANANTNAG 14-03-1977 CASUAL LABOURERS ANWAR BHAT DEPT ANANTNAG PART TIME SWEEPERS IN 2 ANANTNAG REHTI BEGUM GH MOHD WAGAY MATTAN ANNATNAG SW ANANTNAG 07-06-1962 DIFFERENT DEPARTMENTS MOHD PART TIME SWEEPERS IN 3 ANANTNAG RAMZAN MOHD SHABAN AINOO PAHALGAM SW ANANTNAG 06-03-1975 DIFFERENT SHEIKH DEPARTMENTS SHAHZADA FAROOQ AHMAD GULSHANABAD SARNAL DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 4 ANANTNAG 12-03-1968 CASUAL LABOURERS AKTHER BHAT ANANTNAG DEPT ANANTNAG PART TIME SWEEPERS IN ABDUL GANI 5 ANANTNAG HAJRA AKHTER JANGLATMANDI ANANTNAG DSWO ANANTNAG 21-07-1963 DIFFERENT SHEIKH DEPARTMENTS DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 6 ANANTNAG NUSRAT JAN ALI MOHD WAZA SRIGUFWAWA ANANTNAG 24-02-1983 CASUAL LABOURERS DEPT ANANTNAG FEHMEEDA PEER IFRAN MIRMADAN DOORU 7 ANANTNAG DOORU 30-03-1977 SEASONAL LABOURERS AHKTER AHMAD ANANTNAG DISTRICT SOCIAL WELFARE 8 ANANTNAG NIGHAT RASHID AB RASHID WANI HAZRATBAL ANANTNAG 27-06-1977 CASUAL LABOURERS DEPT ANANTNAG http://10.149.2.27/abbisp/AdminReport/District_Wise.aspx[1/17/2018 2:40:49 PM] SWEETY 9 ANANTNAG ALI MOHD WANI NAI BASTI KP ROAD DOORU 01-01-1965 SEASONAL LABOURERS AKHTER SHAHEENA 10 ANANTNAG AB AZIZ NAJAR MOMINABAD ANANTNAG DSWO ANANTNAG 27-11-1977 CASUAL LABOURERS AKHTER PART TIME SWEEPERS IN JASREENA 11 ANANTNAG ABDUL GANI MALIK MIR MAIDAN DOORU SW ANANTNAG 15-03-1994 -

11 Kv TRANSMISSION LINE to ENSURE RELIABLE POWER SUPPLY in REMOTE VILLAGES of LADAKH

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release CC/CCD/2021/PR-NRII/57 11 kV TRANSMISSION LINE TO ENSURE RELIABLE POWER SUPPLY IN REMOTE VILLAGES OF LADAKH Kargil/Gurugram, 30.07.2021 Power Grid Corporation of India Limited (POWERGRID), a Maharatna CPSU under Ministry of Power, Gov- ernment of India has successfully commissioned 40-kms of 11 kV transmission line from Lalung to Darchik under rural electrification scheme namely PMDP (Prime Minister Development Program). The line is used for electrification of enroute adjoining villages namely Lalung, Silmoo, Batalik, Darchik, Hurdass, Sinikcey and Garkon. With commissioning of this line, all remote villages in Aryan Valley (in Kargil district) are now connected to the National Grid through 220 kV Srinagar Leh Transmission System. Earlier, these villages were dependent on DG sets for power supply which was available for limited time only. In addition to above, electrification of 20 villages in Leh district has also been completed by POWERGRID which involves commissioning of remote villages like Largiab in Nubra Valley. Besides, number of 11 kV lines totaling 150 km, connecting villages Wanla to Fatoksar, Lamayaru to Atishe & Fotorse and Saspol area have been established by POWERGRID and it connects all enroute villages. POWERGRID has built a state-of-the-art 220/66 kV Gas Insulated Sub-stations (GIS) at Drass, Kargil, Khalsti and Leh connecting Ladakh region to the national grid through the 341-km of 220 kV transmission line em- anating from Srinagar. 220 kV Srinagar-Leh transmission system has been transferred to POWERGRID as ISTS and we are committed to maintain high system availability and provide reliable power to entire Ladakh re- gion. -

District Census Handbook, Kargil, Part XIII-A & B, Series-8

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 PARTS XIII - A & 8 VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY SERIES-8 VILlAGE& TOWNWISE JAMMU & KASHMIR PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT KARGIL DISTRICT CENSUS DISTRICT HANDBOOK A. H. KHAN of the Indian Administrative Service Di,ector of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Central Government Publications-Census of India 1981-Series 8-Jammu & Kashmir is being published in the following parts. Part No. Subject Part No. Subject (1) (2) (3) 1. AdmiDistration Reports I-A £ Administration Report-Enumeration I-B £ Administration Report-Tabulation II. General Population Tables II-A General Population Tables II-B Primary Census Abstract III. General Economic Tables III-A B-Series Tables of 1st priority III-B B-Series Tables of 2nd priority IV. Social and Cultural Tables IV-A C-Series Tables of 1st priority IV-B C-Series Tables of 2nd priority V. Migration Tables V-A D-Series Tables of 1st priority V-B D-Series Tables of 2nd priority VI. Fertility Tables VI-A F-Series Tables of 1st priority VI-B F-Series Tables of 2nd priority VII. Tables on Houses and disabled population VIII. Household Tables VIII-A HH-Series Tables covering material of constructions of houses VIII-B Contain Tables HH-17, HH-17 SC & HH-17 ST IX. Special, Tables on S. C. and S. T. X. Town Directory Survey Reports on Towns and Villages X-A Town Directory X-B Survey reports on selected towns X-C Survey reports on selected villages XI. Ethnographic studies on S. C. & S. T. XII. Census Atlas . -

Water Harvesting and Conservation Under Cold Desert Condition of Ladakh (J&K): Constraints and Strategies

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2017) 6(2): 1796-1800 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 6 Number 2 (2017) pp. 1796-1800 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article http://dx.doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2017.602.201 Water Harvesting and Conservation under Cold Desert Condition of Ladakh (J&K): Constraints and Strategies Phuntsog Tundup1*, M. A. Wani1, Sonam Dawa2, Shabber Hussain3 and Jigmat Laskit4 1Division of Soil Science, SKUAST-K, Shalimar-190025, India 2Division of FMAP, SKUAST-K, Shalimar-190025, India 3Division of Fruit Science, SKUAST-K, Shalimar-190025, India 4KVK, Nyoma, SKUAST-K, Shalimar-190025, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT K e yw or ds Leh district is situated between 31-36° N latitude and 76-80° E longitude with an Leh, Zing, altitude ranging from 2500 to 6000 m above mean sea level. Leh is the largest Artificial glacier, 2 district in the country with an area of 45,100 Km . Agriculture is the main Seabuckthorn, occupation of the rural people of the district. It was observed that traditional Cold arid. recharge structure practiced in Ladakh was locally called as Zing. Snow is an important source of water in cold arid regions, and the moisture from it is much Article Info more efficiently stored in soil than from rain. Artificial glaciers have been Accepted: innovated. Retaining tall standing stubble after harvest or alternating strips of tall 24 January 2017 Available Online: and short stubble. Re vegetation with seabuck thorn could be successfully used on large scale. 10 February 2017 Introduction Without conservation measures on extremely These old systems of water storing are the fragile terrain, as in the cold-desert condition pavements of modern water harvesting of Ladakh region that has an area of 7.0 mha, systems. -

DL ARTO KARGIL Dec2012 to Sep2015

ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 11/12/2012 TO 30/09/2015 1 Sl No. Licence No Name of the Driver Date of Birth NT Val From -To SIGN OF AUTHORITY Date of Issue Son/Wife/Daughter of Qualification TR Val From -To Receipt Details Permanent Address Blood Group Vehicle Class Temporary Address & Sex Identification Mark 1 JK-0720130002748 MUKHTAR HUSSAIN 01/07/1984 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 MOHD IBRAHIM SSLC Rs.250 /AA-8085/ UMBA SANKOO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 O+ M MCWG LMV UMBA SANKOO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A MOLE ON NOSE. 2 JK-0720130002749 MOHD QASIM 05/02/1991 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 GHULAM ABASS HSC Rs.250 /AA-8479/ SLISKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A+ M MCWG LMV SLISKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A BLACK MOLE ON RT. SHOULDER. 3 JK-0720130002750 TSEWANG YOUNTEN 03/06/1986 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 SONAM ANGCHUK Post Graduation Rs.250 /AA-8480/ RANTAKSHA, ZANSKAR KARGIL LADAKH 194103 B+ M MCWG LMV RANTAKSHA, ZANSKAR KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A BLACK MOLE ON THE LEFT SIDE OF FACE. 4 JK-0720130002751 MOHD ALI 07/02/1988 01/01/2013 31/12/2032 01/01/2013 MOHD HUSSAIN SSLC Rs.250 /AA-8481/ GOMA KARGIL LADAKH JAMMU AND KASHMIR 194103 A+ M MCWG LMV GOMA KARGIL LADAKH JAMMU AND KASHMIR 194103 A MOLE ON RT. ARM. S/W BY NATIONAL INFORMATICS CENTRE ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 11/12/2012 TO 30/09/2015 2 Sl No. -

Kargil - the Unique Land an Overview

Kargil - The Unique Land An Overview Ali Mohamad Rather*** Introduction Pansila in the South3. Present delimitation of Purig (Kargil) is Bodh Ladakh comprises Kharbu to Shamsha Kharbu (In many sub-divisions Drass) and Batalik, Sanjak and Dargo which are in many (Indus valley) to Ringdom ways different from (zanaskar). This may be also called each other. These are specially administrative limits. recognized due to their differentiation in anthropological and religious Kargil etymologically means aspects. Administratively Ladakh is center. There are various divided into Kargil and Leh districts. explanations associated to it. Kargil Kargil is the capital town of Kargil town is centrally located from district. It is traditionally called important places surrounding it like Purig1. Purig is the land from the Srinagar, Gilgit, Leh and Zanakar stream at Lamayur to wanlaand Indus and is more or less equidistant from river (at Khaltse) up to Zojila from one these places. Hence being direction and from Ringdom and equidistant has been given the name Lingshet to river Suru near Indus of Centre or karogil. It is also valley from another direction.2 It is narrated in a local folk lore of Kargil also referred to as, the region which that in ancient times a warrior shot is drained by the Suru and Drass an arrow in one direction. He rivers down to a little below the inquired about the arrow’s place of configuration of river Suru with river fall, saying “Garo Khyl,” i.e. where Indus. From west to east it is from did the arrow fell? The arrow had Drass to pass near Mulbekhchamba fallen in the vicinity of the present and from Kharman, Pakistan town Kargil. -

![Pdf, Accessed 29 July 2019]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8568/pdf-accessed-29-july-2019-3928568.webp)

Pdf, Accessed 29 July 2019]

Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines 51 | 2020 Ladakh Through the Ages. A Volume on Art History and Archaeology, followed by Varia Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sani-Tarungtse in Purig and Zanskar (Ladakh) Le bouddhisme avant la Première Diffusion ? Les cas de Tangol, Dras, Phikhar et Sani-Tarungtse au Purig et au Zanskar (Ladakh) Quentin Devers Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/emscat/4226 DOI: 10.4000/emscat.4226 ISSN: 2101-0013 Publisher Centre d'Etudes Mongoles & Sibériennes / École Pratique des Hautes Études Electronic reference Quentin Devers, “Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sani- Tarungtse in Purig and Zanskar (Ladakh)”, Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines [Online], 51 | 2020, Online since 09 December 2020, connection on 13 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/emscat/4226 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/emscat.4226 This text was automatically generated on 13 July 2021. © Tous droits réservés Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sa... 1 Buddhism before the First Diffusion? The case of Tangol, Dras, Phikhar and Sani-Tarungtse in Purig and Zanskar (Ladakh) Le bouddhisme avant la Première Diffusion ? Les cas de Tangol, Dras, Phikhar et Sani-Tarungtse au Purig et au Zanskar (Ladakh) Quentin Devers Introduction 1 The purpose of this paper is to introduce newly documented sites from Purig and Zanskar that offer a rare insight into an early phase of Buddhism in Ladakh of Central Asian or Kashmiri inspiration. The question of the introduction of Buddhism to Ladakh is usually tied to the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (Tib. -

District Census Handbook, Ladakh, Parts X-A & B, Series-8

CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A & B I TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY SERIES-8 VILLAGE & TOWNWISE JAMMU & KASHMIR PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT LADAKH DISTRICT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK J. N. ZUTSHI of the Kashmir Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir g ::: '" z 0 0 .., ~ I/) e Z ~ Ii . ~ ~ " l • • > l- i •o 0• i' ...0 .. ~ . ·% U ~ II.. ~ . ~ c 0 • W 0 cc: . .., o 0 o 0 ~ 0 N ~ . t- ;: U') Q tR tb • '" 0 N -0 ::? CENSUS OF INDIA 197I LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Central Government Publications-Census ofIndia 1971-Series 8-Jammu & Kashmir is being published in the following parts. Number Subject Covered Part I-A General Report Part I-B General Report Part I-C Subsidiary Tables Part II-A General Population Tables Published Part II-B Economic Tables Part II-C(i) Population by Mother Tongue, Religion, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part II-C(ii) Social & Cultural Tables & Fertility Tables Part III Establishments report & Tables Published Part IV Housing Report & Tables Published Part VI-A Town Directory Published Part VI-B Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns Part VI-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages Part VII I-A !Administration Report on ~numeration Published Part VIII-B tAdministration Report on Tabulation Part IX Census Atlas Part I X-A Administrative Atlas Miscellaneous (i) Study of Gujjars & Bakerwals (ii) Srinagar City DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOKS Part X-A Town & Village Directory Part X-B Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract Part X-C Analytical Report, Administrative Statistics & Uistrict Census Tables tNot for Sale "'District Census Handbooks of Doda, Srinagar, Anantnag, Udhampur, Jammu, Baramula, ;R.ajauri and Punch already published. -

Licence No Name of the Driver Receipt Details Vehicle Class NT

ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 27/02/2012 TO 24/12/2012 1 Sl No. Licence No Name of the Driver Date of Birth NT Val From -To SIGN OF AUTHORITY Date of Issue Son/Wife/Daughter of Qualification TR Val From -To Receipt Details Permanent Address Blood Group Vehicle Class Temporary Address & Sex Identification Mark 1 JK-0720120000786 MURTAZA 15/12/1980 11/04/2012 14/12/2030 05/09/2012 MOHD. HUSSAIN Post Graduation Rs.200 /AA-7162/ CHANGCHIK KARGIL LADAKH 194103 AB+ M MCWG LMV H. NO. 8, KHARDONG PASHKUM, KARGIL LADAKH 194103 A BLACK MOLE ON THE CHIN. 2 JK-0720120002264 SHEIKH MOHD. HUSSAIN 07/08/1963 29/03/2012 06/08/2013 29/03/2012 SHOOKOOR ALI HSC Rs. // SILMO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 Unknown M MCWG LMV SILMO KARGIL LADAKH 194103 3 JK-0720120002265 MOHD. HASSAN 05/04/1978 29/03/2012 04/04/2028 29/03/2012 ASGAR HSC Rs. // HARDASS KARGIL LADAKH 194103 B+ M MCWG LMV HARDASS KARGIL LADAKH 194103 4 JK-0720120002266 KUNCHOK NAMGAIL 02/06/1982 29/03/2012 28/03/2032 29/03/2012 TSERING PUNCHOK HSC Rs. // HENASKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 O+ M MCWG LMV HENASKOTE KARGIL LADAKH 194103 S/W BY NATIONAL INFORMATICS CENTRE ARTO, KARGIL(JK-07) Driving License issue Register For Period 27/02/2012 TO 24/12/2012 2 Sl No. Licence No Name of the Driver Date of Birth NT Val From -To SIGN OF AUTHORITY Date of Issue Son/Wife/Daughter of Qualification TR Val From -To Receipt Details Permanent Address Blood Group Vehicle Class Temporary Address & Sex Identification Mark 5 JK-0720120002267 MOHD. -

Europeans Travellers' Account on Ladakh: a Brief Analysis of The

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.11, No.3, 2020 Europeans Travellers’ Account on Ladakh: A Brief Analysis of the Socio-Economic Aspects in the 19 th Century Ansar Mehdi, Research Scholar, Panjab University. Chandigarh Abstract The regional history of Ladakh has been brought about by the historians in various aspects so far. The European travellers’ assessment about Ladakh has been interpreted in this article while emphasizing the socio-economy of the region in the 19 th century. The major historical trend in the region so far has been the ‘Aryan tribes’ residing mainly in the Dha-Hanu and Darchiks villages of Ladakh. The major European travellers who came to Ladakh in the 19 th century were Alexander Cunningham, William Moorcroft, A.H. Francke and others who left a vast account and it has been a useful source to know the region in historical sense. The economic situation of Ladakh as a country then in the mid 19 th century has been influenced by the Dogras and the British rule which had a great impact on the trade relations and several changes occurred in economical aspects of the region. Ladakh has been mostly under Buddhist monarchic rule in the early 19 th century before the Dogra invasion. This study focuses on the socio-economic changes witnessed as a result of the Dogra and British administration in Ladakh during the 19 th century specially the second half of this century. The ancient trade routes highlight the historical, economic, religious and cultural significance of the region.