Pdf, Accessed 29 July 2019]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Bufotes Latastii (Boulenger, 1882), Endemic to the Western Himalaya

Alytes, 2018, 36 (1–4): 314–327. Distribution of Bufotes latastii (Boulenger, 1882), endemic to the Western Himalaya 1* 1 2,3 4 Spartak N. LITVINCHUK , Dmitriy V. SKORINOV , Glib O. MAZEPA & LeO J. BORKIN 1Institute Of Cytology, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Tikhoretsky pr. 4, St. Petersburg 194064, Russia. 2Department of Ecology and EvolutiOn, University of LauSanne, BiOphOre Building, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 3 Department Of EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy, EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy Centre (EBC), Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. 4ZoOlOgical Institute, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. PeterSburg 199034, Russia. * CorreSpOnding author <[email protected]>. The distribution of Bufotes latastii, a diploid green toad species, is analyzed based on field observations and literature data. 74 localities are known, although 7 ones should be confirmed. The range of B. latastii is confined to northern Pakistan, Kashmir Valley and western Ladakh in India. All records of “green toads” (“Bufo viridis”) beyond this region belong to other species, both to green toads of the genus Bufotes or to toads of the genus Duttaphrynus. B. latastii is endemic to the Western Himalaya. Its allopatric range lies between those of bisexual triploid green toads in the west and in the east. B. latastii was found at altitudes from 780 to 3200 m above sea level. Environmental niche modelling was applied to predict the potential distribution range of the species. Altitude was the variable with the highest percent contribution for the explanation of the species distribution (36 %). urn:lSid:zOobank.Org:pub:0C76EE11-5D11-4FAB-9FA9-918959833BA5 INTRODUCTION Bufotes latastii (fig. 1) iS a relatively cOmmOn green toad species which spreads in KaShmir Valley, Ladakh and adjacent regiOnS Of nOrthern India and PakiStan. -

Current Affairs October 2020

Current Affairs 2020 Current Affairs October 2020 International Day of Rural Women 2020 International Day of Rural Women is celebrated on 15 October. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront and are taking charge by being in the driver's seat. The International Day of Rural Women was created in 1995 by Civil society organizations at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and was declared an official UN Day in 2007 by the UN General Assembly. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront. The theme for this International Day of Rural Women is “Building rural women’s resilience in the wake of COVID-19,” to create awareness of these women’s struggles, their needs, and their critical and key role in our society. Cabinet approved Special Package for UT of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh Union Cabinet has approved a Special Package worth Rs. 520 crore in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh for a period of five years till FY 2023-24 and ensure funding of DeendayalAntyodaya Yojana - National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) in the UTs of Jammu and Kashmir & Ladakh on a demand driven basis without linking allocation with poverty ratio during this extended period. This will ensure sufficient funds under the Mission, as per need to the UTs and is also in line with Government of India's aim to universalize all centrally sponsored beneficiary-oriented schemes in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh in a time bound manner. -

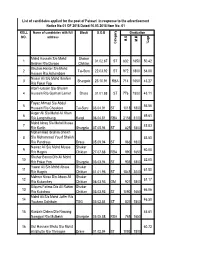

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %Age 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE

Selection List of candidates who have applied for admission to B. Ed Programme (Kargil Chapter) offered through Directorate of Admisssions, University of Kashmir session-2018 Sr. Form No. Name Parentage Address District Category MM MO %age OM 1 1898155 MOHD BAQIR MOHAMMED ALI FAROONA P-O SALISKOTE, KARGIL KARGIL ST 9 7.09 78.78 2 1898735 SHAHAR BANOO MOHAMMAD BAQIR BAROO KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7.87 78.70 3 1895262 FARIDA BANOO MOHD HUSSAIN SHAKAR KARGIL ST 2400 1800 75.00 VILLAGE PASHKUM DISTRICT KARGIL, 4 1897102 HABIBULLAH MOHD BAQIR LADAKH. KARGIL ST 3000 2240 74.67 5 1894751 ANAYAT ALI MOHD SOLEH STICKCHEY CHOSKORE KARGIL ST 2400 1776 74.00 6 1898483 STANZIN SALTON TASHI SONAM R/O MULBEK TEHSIL SHARGOLE KARGIL ST 3000 2177 72.57 7 1892415 IZHAR HUSSAIN NIYAZ ALI TITICHUMIK BAROO POST OFFICE BAROO KARGIL ST 3600 2590 71.94 8 1897301 MOHD HASSAN HADIRE MOHD IBRAHIM HARDASS GRONJUK THANG KARGIL KARGIL ST 3100 2202 71.03 9 1896791 MOHD HUSSAIN GHULAM MOHD ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL KARGIL ST 4000 2835 70.88 10 1898160 MOHD HUSSAIN MOHD TOHA KHANGRAL,CHIKTAN,KARGIL KARGIL ST 3400 2394 70.41 11 1898257 MARZIA BANOO MOHD ALI R/O SAMRAH CHIKTAN KARGIL KARGIL ST 10 7 70.00 12 1893813 ZAIBA BANOO KACHO TURAB SHAH YABGO GOMA KARGIL KARGIL ST 2100 1466 69.81 13 1894898 MEHMOOD MOHD ALI LANKERCHEY KARGIL ST 4000 2784 69.60 14 1894959 SAJAD HUSSAIN MOHD HASSAN ACHAMBORE TAISURU KARGIL ST 3000 2071 69.03 15 1897813 IMRAN KHAN AHMAD KHAN CHOWKIAL DRASS KARGIL RBA 4650 3202 68.86 16 1897210 ARCHO HAKIMA SYED ALI SALISKOTE TSG KARGIL ST 500 340 68.00 17 -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Kargil Operation 1999

KARGIL OPERATION 1999 The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict was an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LOC). In India, the conflict is also referred to as Operation Vijay which was the name of the Indian operation to clear the Kargil sector.The war is the most recent example of high-altitude warfare in mountainous terrain, and as such posed significant logistical problems for the combating sides.The cause of the war was the infiltration of Pakistani soldiers disguised as Kashmiri militants into positions on the Indian side of the LOC which serves as the border between the two states. During the initial stages of the war, Pakistan blamed the fighting entirely on independent Kashmiri insurgents, but documents left behind by casualties and later statements by Pakistan's Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff showed involvement of Pakistani paramilitary forces led by General Ashraf Rashid. The Indian Army, later supported by the Indian Air Force, recaptured a majority of the positions on the Indian side of the LOC infiltrated by the Pakistani troops and militants. Facing international diplomatic opposition, the Pakistani forces withdrew from the remaining Indian positions along the LOC. There were three major phases to the Kargil War. First, Pakistan infiltrated forces into the Indian-controlled section of Kashmir and occupied strategic locations enabling it to bring NH1 within range of its artillery fire. The next stage consisted of India discovering the infiltration and mobilising forces to respond to it. -

VEIL of KASHMIR Poetry of Travel and Travail in Zhangzhungpa’S 15Th-Century Kāvya Reworking of the Biography of the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (958- 1055 CE)

VEIL OF KASHMIR Poetry of Travel and Travail in Zhangzhungpa’s 15th-Century Kāvya Reworking of the Biography of the Great Translator Rinchen Zangpo (958- 1055 CE) by Dan Martin n November of 1987, I visited Samten G. Karmay at his office, then on Rue du Président Wilson in Paris. With over twenty I years’ distance, and indeed that many years older, it is difficult to recall exactly what words were spoken during that meeting. As you get older you tend to look back on your past and identify particular turning points, discerning paths both taken and not taken. You are forced to become a historian of your own life. Suspended as I was in a veritable bardo between the incipient stages of that dreaded academic disease known as dissertationitis at a North American university and my second and longest sojourn in South Asia, I do not believe I was aware at the time just how important this meeting would be for setting me steadily on a course of research into 11th- and 12th-century Tibetan history, and especially the history of the Bon religion. In a word, it was inspirational. In 1996, the last week of June, I attended a conference in the Spiti valley, quite near the border with Tibet, in Himachal Pradesh. It was a very long and tiring but eventful three-day bus trip from Delhi via Simla and Kinnaur. This conference was intended as a millennial cele- bration for Tabo Monastery’s founding by Rinchen Zangpo in 996 CE. So needless to say, many of the papers were devoted to the Great Translator. -

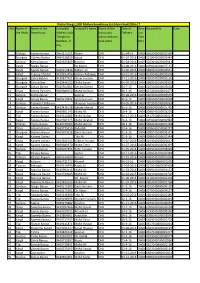

List of Candidates Applied for the Post of General Line Teacher In

List of candidates applied for the post of General Line Teacher in response to the advertisement Notice No:02 OF 2018 Dated:15.03.2018 Item No: 01 Graduation P.G B.Ed M.Ed Name of candidates with full ROLL NO. Block Stream JRF address P.hD M.Phill M.O M.O M.O M.O NET/SET M.M M.M M.M M.M Category %age %age %age %age Mohd Ibrahim S/0 Mirza Ali S/0 1 Saliskote TSG 02.04.91 ST 900 1800 50.00 6 10 60.00 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts Tohera Banoo D/0 Haji Mohd 2 Hassan R/0 Andoo Shargol 02.04.93 ST 908 1800 50.44 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts Kaniz Fatima D/0 Mohd Toha 3 R/0 Taisuru Taisuru 06.08.91 RBA 1012 1800 56.22 0 0 #DIV/0! 742 900 82.44 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts Saleema Khanum D/0 Mohd 4 Ali Khan R/0 Balti Bazar Kargil 03.12.90 RBA 892 1800 49.56 6.3 10 63.00 709 900 78.78 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts Farida Batool D/0 haji Hadi R/0 5 Staikchey Kargil Kargil 04.03.89 ST 769 1800 42.72 549 1000 54.90 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts Sajida Batool D/0 Mohmmad 6 Sadiq R/0 Stikchey Kargil 15.01.93 ST 893 1650 54.12 1805 3200 56.41 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts Mohd Jaffar S/0 Ali Mohd R/0 7 Saliskote TSG 10.11.89 ST 845 1800 46.94 656 1000 65.60 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Arts 8 Imran Ali Khan S/0 Mohd Ali Kargil 05.12.87 RBA 1023 1800 56.83 1512 2500 60.48 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! Net 0 0 0 Medical Khan R/0 Balti Bazar 9 Syeda Batool D/0 Haji Hadi Kargil 14.03.93 ST 849 1650 51.45 931 1800 51.72 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 #DIV/0! 0 0 0 0 Ats R/0 Staikchey 10 Gulshan Arah D/0 Abdul Aziz Drass 02.03.89 ALC 765 1800 -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 19, March 2005 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Nicky Grist - In Appreciation John Bray 4 Call for Papers: 12th Colloquium at Kargil 9 News from Ladakh, including: Morup Namgyal wins Padmashree Thupstan Chhewang wins Ladakh Lok Sabha seat Composite development planned for Kargil News from Members 37 Articles: The Ambassador-Teacher: Reflections on Kushok Bakula Rinpoche's Importance in the Revival of Buddhism in Mongolia Sue Byrne 38 Watershed Development in Central Zangskar Seb Mankelow 49 Book reviews: A Checklist on Medicinal & Aromatic Plants of Trans-Himalayan Cold Desert (Ladakh & Lahaul-Spiti), by Chaurasia & Gurmet Laurent Pordié 58 The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovitch and his Fraudulent Gospel, by H. Louis Fader John Bray 59 Trance, Besessenheit und Amnesie bei den Schamanen der Changpa- Nomaden im Ladakhischen Changthang, by Ina Rösing Patrick Kaplanian 62 Thesis reviews 63 New books 66 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 14 68 Notes on Contributors 72 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL I should begin by apologizing for the fact that this issue of Ladakh Studies, once again, has been much delayed. In light of this, we have decided to extend current subscriptions. Details are given elsewhere in this issue. Most recently we postponed publication, because we wanted to be able to announce the place and exact dates for the upcoming 12th Colloquium of the IALS. We are very happy and grateful that our members in Kargil will host the colloquium from July 12 through 15, 2005. -

The Tibetan Translation of the Indian Buddhist Epistemological Corpus

187 The Tibetan Translation of the Indian Buddhist Epistemological Corpus Pascale Hugon* As Buddhism was transmitted to Tibet, a huge number of texts were translated from Sanskrit, Chinese and other Asian languages into Tibetan. Epistemological treatises composed by In dian Buddhist scholars – works focusing on the nature of »valid cognition« and exploring peripheral issues of philosophy of mind, logic, and language – were, from the very beginning, part of the translated corpus, and had a profound impact on Tibetan intellectual history. This paper looks into the progression of the translation of such works in the two phases of the diffusion of Buddhism to Tibet – the early phase in the seventh to the ninth centuries and the later phase starting in the late tenth century – on the basis of lists of translated works in various catalogues compiled in these two phases and the contents of the section »epistemo logy« of canonical collections (Tenjur). The paper inquires into the prerogatives that directed the choice of works that were translated, the broader or narrower diffusion of existing trans lations, and also highlights preferences regarding which works were studied in particular contexts. I consider in particular the contribution of the famous »Great translator«, Ngok Loden Shérap (rngog blo ldan shes rab, 10591109), who was also a pioneer exegete, and discuss some of the practicalities and methodology in the translation process, touching on the question of terminology and translation style. The paper also reflects on the status of translated works as authentic sources by proxy, and correlatively, on the impact of mistaken translations and the strategies developed to avoid them. -

1000+ Question Series PDF -Jklatestinfo

JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q1) The kashmir Valley was originally a huge lake called ? a) Manesar b) Neelam c) Satisar d) Both ‘b’ & ‘c’ Q2) Kalhana , a famous historian wrote ? a) Nilmatpurana b) Rajtarangini c) Both d) None of these Q3) The First king mentioned by Kalhana is ? a) Gonanda I b) Durlabha Vardhana c) Ashoka d) Jalodbhava Q4) The outer plains doesn’t cover which of the following ? a) RS Pura b) Kathua c) Akhnoor d) Udhampur Q5) When J&K became Union Territory ? a) August 5, 2019 b) October 31, 2019 c) September 5, 2019 d) October 1 , 2019 JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q6) Which among the following is the welcome dance for spring season ? a) Bhand Pathar b) Dhumal c) Kud d) Rouf Q7) Total number of districts in J&K ? a) 22 b) 21 c) 20 d) 18 Q8) On which hill the Vaishno Devi Mandir is located ? a) Katra b) Trikuta c) Udhampur d) Aru Q9) The SI unit of charge is ? a) Ampere b) Coulomb c) Kelvin d) Watt Q10) The filament of light bulb is made up of ? a) Platinum b) Antimony c) Tungsten d) Tantalum JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q11) Battle of Plassey was fought in ? a) 1757 b) 1857 c) 1657 d) 1800 Q12) Indian National Congress was formed by ? a) WC Bannerji b) George Yuli c) Dada Bhai Naroji d) A.O HUme Q13) The Tropic of cancer doesn’t pass through ? a) MP b) Odisha c) West Bengal d) Rajasthan Q14) Which of the following is Trans-Himalyan River ? a) Ganga b) Ravi c) Yamuna d) Indus Q15) Rovers cup is related to ? a) Hockey b) Cricket c) Football d) Cricket JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ -

S.No Name of the Block Name of the Beneficiary Complete Address With

District Kargil_JSSK Mother Beneficiary List (April-Sept)2016-17 S.No Name of Name of the Complete Husband's Name Name of the Date of Amo Account No Date the Block Beneficiary Address with Institution Delivery unt Telephone where delivery Paid Number , If took place. (Rs.) any 1 Chiktan Fatima Banoo 9469275121 Nizam DHK 25-04-16 1400 0683040100003360 2 Shargole Hakima Banoo 9469238929 Sajjad DHK 04-07-2016 1400 1219040100002445 3 Sankoo Khera banoo 9469625809 Ibrahim DHK 04-04-2016 1400 0203040100009042 4 Kargil Nargis Banoo Gh Mohd DHK 03-08-2016 1400 0096040100037135 5 Kargil Sayida Banoo 9469214849 Zulfqar ali DHK 04-06-2016 1400 0683040100002551 6 Kargil Tsering Choskit 9419553496 Stanzin Rabzang DHK 04-01-2016 1400 0349040100030505 7 Shargole Zahra Batool 9419847951 Nissar hussain DHK 04-11-2016 1400 0683040100003166 8 Shargole Zainab Bee 9419446150 Mohd hasan DHK 04-09-2016 1400 0683040100003310 9 Shargole Zakiya Banoo 9419502461 Stering Dorjay DHK 24-7-15 1400 0203040100003018 10 Drass Amina Parveen 9469389150 Mohd Suliman DHK 30-3-16 1400 0372040100023477 11 Sankoo Archo Zakiya Syed ali DHK 09-08-2016 1400 0203040100005570 12 Kargil Assiya Banoo 9469230822 Feroz Hussain DHK 26-3-16 1400 0096040100023028 13 Sankoo Fareeda Tabbasum Manzoor hussain DHK 04-05-2016 1400 0203040100009063 14 Sankoo Fatima Banoo 9419476728 Zaheer ahmad DHK 25-3-16 1400 0096040100025769 15 Kargil Fatima Banoo 9469661143 Mohd Ali DHK 18-4-16 1400 0096040100033220 16 TSg Fatima Banoo 9419310285 Mohd Gulzar DHK 04-11-2016 1400 0617040860000021 17 Kargil Fatima