The Politics of Being Buddhist in Zangskar: Partition and Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact of Climatic Change on Agro-Ecological Zones of the Suru-Zanskar Valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India

Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Vol. 3(13), pp. 424-440, 12 November, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE ISSN 2006 - 9847©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Impact of climatic change on agro-ecological zones of the Suru-Zanskar valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India R. K. Raina and M. N. Koul* Department of Geography, University of Jammu, India. Accepted 29 September, 2011 An attempt was made to divide the Suru-Zanskar Valley of Ladakh division into agro-ecological zones in order to have an understanding of the cropping system that may be suitably adopted in such a high altitude region. For delineation of the Suru-Zanskar valley into agro-ecological zones bio-physical attributes of land such as elevation, climate, moisture adequacy index, soil texture, soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity have been taken into consideration. The agricultural productivity of the valley has been worked out according to Bhatia’s (1967) productivity method and moisture adequacy index has been estimated on the basis of Subrmmanyam’s (1963) model. The land use zone map has been superimposed on moisture adequacy index, soil texture and soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity zones to carve out different agro-ecological boundaries. The five agro-ecological zones were obtained. Key words: Agro-ecology, Suru-Zanskar, climatic water balance, moisture index. INTRODUCTION Mountain ecosystems of the world in general and India in degree of biodiversity in the mountains. particular face a grim reality of geopolitical, biophysical Inaccessibility, fragility, diversity, niche and human and socio economic marginality. -

Distribution of Bufotes Latastii (Boulenger, 1882), Endemic to the Western Himalaya

Alytes, 2018, 36 (1–4): 314–327. Distribution of Bufotes latastii (Boulenger, 1882), endemic to the Western Himalaya 1* 1 2,3 4 Spartak N. LITVINCHUK , Dmitriy V. SKORINOV , Glib O. MAZEPA & LeO J. BORKIN 1Institute Of Cytology, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Tikhoretsky pr. 4, St. Petersburg 194064, Russia. 2Department of Ecology and EvolutiOn, University of LauSanne, BiOphOre Building, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland. 3 Department Of EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy, EvOlutiOnary BiOlOgy Centre (EBC), Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. 4ZoOlOgical Institute, Russian Academy Of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 1, St. PeterSburg 199034, Russia. * CorreSpOnding author <[email protected]>. The distribution of Bufotes latastii, a diploid green toad species, is analyzed based on field observations and literature data. 74 localities are known, although 7 ones should be confirmed. The range of B. latastii is confined to northern Pakistan, Kashmir Valley and western Ladakh in India. All records of “green toads” (“Bufo viridis”) beyond this region belong to other species, both to green toads of the genus Bufotes or to toads of the genus Duttaphrynus. B. latastii is endemic to the Western Himalaya. Its allopatric range lies between those of bisexual triploid green toads in the west and in the east. B. latastii was found at altitudes from 780 to 3200 m above sea level. Environmental niche modelling was applied to predict the potential distribution range of the species. Altitude was the variable with the highest percent contribution for the explanation of the species distribution (36 %). urn:lSid:zOobank.Org:pub:0C76EE11-5D11-4FAB-9FA9-918959833BA5 INTRODUCTION Bufotes latastii (fig. 1) iS a relatively cOmmOn green toad species which spreads in KaShmir Valley, Ladakh and adjacent regiOnS Of nOrthern India and PakiStan. -

Current Affairs October 2020

Current Affairs 2020 Current Affairs October 2020 International Day of Rural Women 2020 International Day of Rural Women is celebrated on 15 October. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront and are taking charge by being in the driver's seat. The International Day of Rural Women was created in 1995 by Civil society organizations at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and was declared an official UN Day in 2007 by the UN General Assembly. From agriculture to food security, nutrition, land and natural resource management, domestic care and work, rural women are at the forefront. The theme for this International Day of Rural Women is “Building rural women’s resilience in the wake of COVID-19,” to create awareness of these women’s struggles, their needs, and their critical and key role in our society. Cabinet approved Special Package for UT of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh Union Cabinet has approved a Special Package worth Rs. 520 crore in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh for a period of five years till FY 2023-24 and ensure funding of DeendayalAntyodaya Yojana - National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM) in the UTs of Jammu and Kashmir & Ladakh on a demand driven basis without linking allocation with poverty ratio during this extended period. This will ensure sufficient funds under the Mission, as per need to the UTs and is also in line with Government of India's aim to universalize all centrally sponsored beneficiary-oriented schemes in the UTs of J&K and Ladakh in a time bound manner. -

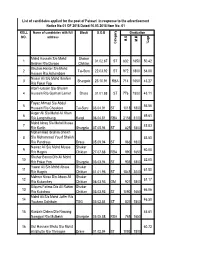

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Reru Valley Expedition Proposal 2011

RERU VALLEY EXPEDITION PROPOSAL 2011 FOREWORD The destination of this expedition is to the Reru valley in the Zanskar range. This range is located in the north East of India in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, between the Great Himalayan range and the Ladakh range. Until 2009 there had been no climbing expeditions to the valley, and there are a large number of unclimbed summits between 5700m and 6200m in this area: only two of the 36 identified peaks have seen ascents. Our expedition aims to take a large group of 7 members that will use a single base camp but split into two teams that will attempt different types of objective. One team will focus on technical rock climbing ascents, whilst the other team will focus on alpine style mixed snow and rock ascents of unclimbed peaks with a target elevation of around 6000m. CONTENTS 1. Expedition Aims & Objectives ............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Itinerary ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Expedition Team ............................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Logistics ............................................................................................................................................................ -

A Pilot Survey of the Avifauna of Rangdum Valley, Kargil, Ladakh (Indian Trans-Himalaya)

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 May 2015 | 7(6): 7274–7281 A pilot survey of the avifauna of Rangdum Valley, Kargil, Ladakh (Indian Trans-Himalaya) ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) 1 2 3 Short Communication Short Tanveer Ahmed , Afifullah Khan & Pankaj Chandan ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) 1,2 Aligarh Muslim University, Department of Wildlife Sciences, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh 202002, India OPEN ACCESS 3 WWF-India, 172-B, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi 110003, India 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected],3 [email protected] Abstract: An avifaunal survey of Rangdum Valley in Kargil District, Pradesh) and Ladakh (Jammu & Kashmir) at an average Jammu & Kashmir, India was carried out between June and July 2011. altitude of over 4000m. In Ladakh, studies on avifauna McKinnon’s species richness and total count methods were used. A total of 69 species were recorded comprising six passage migrants, were initiated by A.L. Adam as early as 1859 (Adam 25 residents, 36 summer visitors and three vagrants. The recorded 1859). Some avifaunal surveys in this region were species represents seven orders and 24 families, accounting for 23% th of the species known from Ladakh. A majority of the bird species are carried out in early 20 century (Ludlow 1920; Wathen insectivores. 1923; Osmaston 1925, 1927). Later, more studies on avian species in different parts of Ladakh were Keywords: Avifauna, feeding guild, Ladakh, Rangdum Valley, status. carried out by Holmes (1986), Mallon (1987), Mishra & Humbert-Droz (1998), Singh & Jayapal (2000), Pfister The Himalaya constitute one of the richest and (2001), Namgail (2005), Sangha & Naoroji (2005a,b), most unique ecosystems on the earth. -

YOUR ROMANTIC GETAWAY in BEAUTIFUL BALTISTAN! Royal Palaces, Fortresses, Adventure and the Authentic Baltistan! – 5 Days / 4 Nights

YOUR ROMANTIC GETAWAY IN BEAUTIFUL BALTISTAN! Royal Palaces, Fortresses, Adventure and the Authentic Baltistan! – 5 days / 4 nights EXPERIENCE SERENA HOTELS. EXPERIENCE GILGIT-BALTISTAN NAME: Your Romantic Getaway in Beautiful Baltistan: Royal Palaces, Fortresses, Adventure & the Authentic Baltistan LENGTH OF TIME: 5 days with options to extend and the option of staying in the Islamabad Serena Hotel BEST TIME TO TRAVEL: Anytime from April through to November! Day Destination / Drive Accommodation Details Activities & Highlights Optional Experiences Visual Reflection time 1 Skardu Khaplu Palace & Residence Get your cameras charged and ready for an ultimate You have just arrived so we suggest you (55 minute scenic flight) (Full board) – Heritage Boutique Hotel romantic getaway of awe inspiring scenery. take it easy today. Deluxe Heritage Room Khaplu Click here for more information Arrive in time for a late lunch. Top Tip #1: Stop in Skardu bazaar to (2 ½ hour’s drive) purchase some local dried apricots & Take a guided historical tour of the beautifully restored almonds. A great snack to overcome a Supplement: Khaplu Palace & Residence. hungry tummy on your journey. Treat yourselves to the royal suite in the old Palace – enjoy the privacy of your own Spend the afternoon exploring the historical & cultural Top Tip #2: Take your pic at the sitting room with superb views over Khaplu beauty of Khaplu. junction of two powerful rivers – where & the towering mountains. the Indus River meets the Shyok River. A Visit the imposing historic Khaplu Khanqah and its great moment to capture! newer addition being built by the community in tradition style. Witness the game of the kings when the locals of Khaplu jump on their horses for View the UNESCO award winning tomb of the saint a chukka or two of authentic Polo. -

OU1901 092-099 Feature Cycling Ladakh

Cycling Ladakh Catching breath on the road to Rangdum monastery PICTURE CREDIT: Stanzin Jigmet/Pixel Challenger Breaking the There's much more to Kate Leeming's pre- Antarctic expeditions than preparation. Her journey in the Indian Himalaya was equally about changing peoples' lives. WORDS Kate Leeming 92 93 Cycling Ladakh A spectacular stream that eventually flows into the Suru River, on the 4,000m plains near Rangdum nergy was draining from my legs. My heart pounded hard and fast, trying to replenish my oxygen deficit. I gulped as much of the rarified air as I could, without great success; at 4,100m, the atmospheric oxygen is at just 11.5 per cent, compared to 20.9 per cent at sea level. As I continued to ascend towards the snow-capped peaks around Sirsir La pass, the temperature plummeted and my body, drenched in a lather of perspiration, Estarted to get cold, further sapping my energy stores. Sirsir La, at 4,828m, is a few metres higher than Europe’s Mont Blanc, and I was just over half way up the continuous 1,670m ascent to get there. This physiological response may have been a reality check, but it was no surprise. The ride to the remote village of Photoksar on the third day of my altitude cycling expedition in the Indian Himalaya had always loomed as an enormous challenge, and I was not yet fully acclimatised. I drew on experience to pace myself: keeping the pedals spinning in a low gear, trying to relax as much as possible and avoiding unnecessary exertion. -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Kargil Operation 1999

KARGIL OPERATION 1999 The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict was an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LOC). In India, the conflict is also referred to as Operation Vijay which was the name of the Indian operation to clear the Kargil sector.The war is the most recent example of high-altitude warfare in mountainous terrain, and as such posed significant logistical problems for the combating sides.The cause of the war was the infiltration of Pakistani soldiers disguised as Kashmiri militants into positions on the Indian side of the LOC which serves as the border between the two states. During the initial stages of the war, Pakistan blamed the fighting entirely on independent Kashmiri insurgents, but documents left behind by casualties and later statements by Pakistan's Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff showed involvement of Pakistani paramilitary forces led by General Ashraf Rashid. The Indian Army, later supported by the Indian Air Force, recaptured a majority of the positions on the Indian side of the LOC infiltrated by the Pakistani troops and militants. Facing international diplomatic opposition, the Pakistani forces withdrew from the remaining Indian positions along the LOC. There were three major phases to the Kargil War. First, Pakistan infiltrated forces into the Indian-controlled section of Kashmir and occupied strategic locations enabling it to bring NH1 within range of its artillery fire. The next stage consisted of India discovering the infiltration and mobilising forces to respond to it. -

Pakistan S Strategic Blunder at Kargil, by Brig Gurmeet

Pakistan’s Strategic Blunder at Kargil Gurmeet Kanwal Cause of Conflict: Failure of 10 Years of Proxy War India’s territorial integrity had not been threatened seriously since the 1971 War as it was threatened by Pakistan’s ill-conceived military adventure across the Line of Control (LoC) into the Kargil district of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) in the summer months of 1999. By infiltrating its army soldiers in civilian clothes across the LoC, to physically occupy ground on the Indian side, Pakistan added a new dimension to its 10-year-old ‘proxy war’ against India. Pakistan’s provocative action compelled India to launch a firm but measured and restrained military operation to clear the intruders. Operation ‘Vijay’, finely calibrated to limit military action to the Indian side of the LoC, included air strikes from fighter-ground attack (FGA) aircraft and attack helicopters. Even as the Indian Army and the Indian Air Force (IAF) employed their synergised combat potential to eliminate the intruders and regain the territory occupied by them, the government kept all channels of communication open with Pakistan to ensure that the intrusions were vacated quickly and Pakistan’s military adventurism was not allowed to escalate into a larger conflict. On July 26, 1999, the last of the Pakistani intruders was successfully evicted. Why did Pakistan undertake a military operation that was foredoomed to failure? Clearly, the Pakistani military establishment was becoming increasingly frustrated with India’s success in containing the militancy in J&K to within manageable limits and saw in the Kashmiri people’s open expression of their preference for returning to normal life, the evaporation of all their hopes and desires to bleed India through a strategy of “a thousand cuts”. -

Contemporary Ladakh: Identifying the “Other” in Buddhist-Muslim

Issue Brief # 234 August 2013 Innovative Research | Independent Analysis | Informed Opinion Contemporary Ladakh Identifying the “Other” in Buddhist-Muslim Transformative Relations Sumera Shafi Jawaharlal Nehru University Changes in the relationship of major sub- identity being a fluid concept is often divisions of a society are reflected in the misappropriated by a certain section of development of active scholarly analysis the society for the furtherance of their of those changes. The ongoing interests. It is the age old congenial inter- transformations in the Ladakhi society communal networks that face the brunt of have also attracted certain amount of such maneuverings leading to irrevocable attention from scholars from within and transformations in the everyday relations. outside the area. Currently there is a select list of material for one to be able to This essay is mainly based on available evaluate the trajectory of social change literature and keen observations made as in Ladakh and also to identify the a native of Ladakh. The conclusions are causative factors for such change. In that preliminary in nature and aimed at the direction this paper seeks to specify the possibility of bringing out a theoretical process of identity formation amongst the standpoint through the use of empirical Ladakhis by emphasizing how the data. differential circumstances faced by the Who is the other? locals has led them to approximate religion as the prime identity marker. This essay does not aim at identifying the Through the illustration of Ladakh’s other but in contrast it is an attempt to experience, this essay seeks to argue that illustrate the complexity involved in doing just that! Identity is a fluid concept and there are This essay was initially presented in a multiple identities which an individual can conference organized by the IPCS in approximate based on various collaboration with the India circumstances.