Endangered Oral Tradition in Zanskar Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

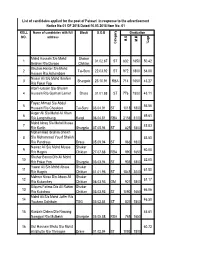

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Contemporary Ladakh: Identifying the “Other” in Buddhist-Muslim

Issue Brief # 234 August 2013 Innovative Research | Independent Analysis | Informed Opinion Contemporary Ladakh Identifying the “Other” in Buddhist-Muslim Transformative Relations Sumera Shafi Jawaharlal Nehru University Changes in the relationship of major sub- identity being a fluid concept is often divisions of a society are reflected in the misappropriated by a certain section of development of active scholarly analysis the society for the furtherance of their of those changes. The ongoing interests. It is the age old congenial inter- transformations in the Ladakhi society communal networks that face the brunt of have also attracted certain amount of such maneuverings leading to irrevocable attention from scholars from within and transformations in the everyday relations. outside the area. Currently there is a select list of material for one to be able to This essay is mainly based on available evaluate the trajectory of social change literature and keen observations made as in Ladakh and also to identify the a native of Ladakh. The conclusions are causative factors for such change. In that preliminary in nature and aimed at the direction this paper seeks to specify the possibility of bringing out a theoretical process of identity formation amongst the standpoint through the use of empirical Ladakhis by emphasizing how the data. differential circumstances faced by the Who is the other? locals has led them to approximate religion as the prime identity marker. This essay does not aim at identifying the Through the illustration of Ladakh’s other but in contrast it is an attempt to experience, this essay seeks to argue that illustrate the complexity involved in doing just that! Identity is a fluid concept and there are This essay was initially presented in a multiple identities which an individual can conference organized by the IPCS in approximate based on various collaboration with the India circumstances. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

Himalayan Journal of Sciences Vol 2 Issue 4 (Special Issue) July 2004

EXTENDED ABSTRACTS: 19TH HIMALAYA-KARAKORAM-TIBET WORKSHOP, 2004, NISEKO, JAPAN Biostratigraphy and biogeography of the Tethyan Cambrian sequences of the Zanskar Ladakh Himalaya and of associated regions Suraj K Parcha Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, 33 - Gen. Mahadeo Singh Road, Dehra Dun -248 001, INDIA For correspondence, E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... The Cambrian sections studied so far exhibit 4 km thick and North America Diplagnostus has been reported from the Lejopyge apparently conformable successions of Neoproterozoic and laevigata Zone which characterizes the latest Middle Cambrian. Cambrian strata in Zanskar - Spiti basins. The Cambrian In the Lingti valley of the Zanskar area the presence of Lejopyge sediments of this area are generally fossiliferous comprising sp. is also of stratigraphic importance as it underlies the trilobites, trace fossils, hylothids, cystoids, archaeocythid and characteristic early Late Cambrian faunal elements. In the Magam brachiopod, etc. In parts of Zanskar – Spiti and Kashmir region section of Kashmir the Diplagnostus occurs at the top of the rich trilobite fauna is collected from the Cambrian successions. Shahaspis (=Bolaspidella) Zone of Jell and Hughes (1997), that is The trilobites constitute the most significant group of fossils, overlain by the Damesella Zone, which contains characteristic which are useful not only for the delimination of various biozones faunal elements of Changhian early Late Cambrian age. The but also for the reconstruction of the Cambrian paleogeography genus Damesella is also reported from the Kushanian stage in of the region. China, the Tiantzun Formation in Korea and from Agnostus The Zanskar basin together with a part of the Spiti basin pisiformis Zone of the Outwood Formation in Britain. -

Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019

Current Affairs Q&A PDF Current Affairs Q&A PDF 2019 Contents Current Affairs Q&A – May 2019 .......................................................................................................................... 2 INDIAN AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ......................................................................................................................... 28 BANKING & FINANCE .................................................................................................................................. 51 BUSINESS & ECONOMY .............................................................................................................................. 69 AWARDS & RECOGNITIONS....................................................................................................................... 87 APPOINTMENTS & RESIGNS .................................................................................................................... 106 ACQUISITIONS & MERGERS .................................................................................................................... 128 SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 129 ENVIRONMENT ........................................................................................................................................... 146 SPORTS -

Buddhist Traditional Ethics: a Source of Sustainable Biodiversity Examining Cases Amongst Buddhist Communities of Nepal, Leh- Ladakh and North-East Region of India

Buddhist Traditional Ethics: A Source of Sustainable Biodiversity Examining cases amongst Buddhist communities of Nepal, Leh- Ladakh and North-East Region of India Dr. Anand Singh SAARC/CC/Research Grant 13-14 (24 September, 2014) Acknowledgement The opportunity to get this project is one of the important turning points in my academic pursuits. It increased my hunger to learn Buddhism and engage its tradition in social spectrum. Though the project is a symbolical presentation of Buddhist cultural and ethical values existing in Ladakh, Lumbini and Tawang. But it gives wide scope, specially me to learn, identify and explore more about these societies. My several visits in Ladakh has provided me plethora of knowledge and material to continue my research to produce a well explored monograph on Ladakh. I wish that I would be able to complete it in near future. I do acknowledge that report gives only peripheral knowledge about the theme of the project. It is dominantly oriented to Himalayan ranges of Ladakh. But in such short time, it was not possible to go for deep researches on these perspectives. However I have tried to keep my ideas original and tried for new orientation to early researches on topic. In future these ideas will be further elaborated and published. I take this opportunity for recording my heartiest thanks to SAARC Cultural Centre for granting me fellowship and giving me opportunity to explore new, traditional but still relevant and useful ideas related to traditional knowledge of Buddhism. My grateful thanks to Dr. Sanjay Garg, Deputy Director (Research), SAARC Cultural Centre for always giving new and innovative ideas for research. -

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh

The Rock Art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’ Laurianne Bruneau & John Vincent Bellezza I. An introduction to the rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh his paper examines common thematic and esthetic features discernable in the rock art of the western portion of the T Tibetan plateau.1 This rock art is international in scope; it includes Ladakh (La-dwags, under Indian jurisdiction), Tö (Stod) and the Changthang (Byang-thang, under Chinese administration) hereinafter called Upper Tibet. This highland rock art tradition extends between 77° and 88° east longitude, north of the Himalayan range and south of the Kunlun and Karakorum mountains. [Fig.I.1] This work sets out the relationship of this art to other regions of Inner Asia and defines what we call the ‘Western Tibetan Plateau Style’. The primary materials for this paper are petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings). They comprise one of the most prolific archaeological resources on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Although pictographs are quite well distributed in Upper 1 Bellezza would like to heartily thank Joseph Optiker (Burglen), the sole sponsor of the UTRAE I (2010) and 2012 rock art missions, as well as being the principal sponsor of the UTRAE II (2011) expedition. He would also like to thank David Pritzker (Oxford) and Lishu Shengyal Tenzin Gyaltsen (Gyalrong Trokyab Tshoteng Gön) for their generous help in completing the UTRAE II. Sponsors of earlier Bellezza expeditions to survey rock art in Upper Tibet include the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation (New York) and the Asian Cultural Council (New York). -

LADAKH: Das Verborgene Königreich Zanskar Trekkingtour Durch Die Abgelegenen Täler Des Königreichs Zanskar

Detailprogramm Ladakh – Zanskar LADAKH: Das verborgene Königreich Zanskar Trekkingtour durch die abgelegenen Täler des Königreichs Zanskar Detailprogramm 1 Tag: Ankunft in Indien und Weiterflug nach Srinagar Ankunft in Neu-Delhi in den frühen Morgenstunden. Nach der Einreise nach Indien geht es noch am selben Vormittag weiter nach Srinagar, der Hauptstadt von Kashmir. In Srinagar werden wir in einem Hausboot am malerischen Dal-See untergebracht. Der restliche Tag steht zur freien Verfügung um die legendäre Stadt zu erkunden, sich nach der langen Anreise zu erholen bzw. sich auf die Weiterreise in den nahen Himalaya vorzubereiten. (M, A) 2 Tag: Fahrt von Srinagar nach Kargil Vor unserer Abfahrt aus Srinagar haben wir Zeit die berühmten Mogul Gärten zu besichtigen. Die beeindruckenden Gärten wurden im Jahre 1619 vom damaligen Mogul Kaiser Jahangir zu Ehren seiner Frau erbaut und sind nach persischen Vorbildern gestaltet. Nach dem gemütlichen Besuch geht es auf guter Strasse von Srinagar nach Osten und ins Himalaya Gebirge bis nach Kargil, wo wir uns in einer kleinen Pension einquartieren. Fahrt: ca. 215 Km, Fahrtzeit: ca. 5-6 Std. (F, M, A) 3 Tag: Fahrt von Kargil nach Rangdum Die heutige Fahrt führt uns entlang des Suru Tales tief in das mächtige Himalaya Gebirge. In Kargil lassen wir die gut asphaltierte Straße hinter uns und auf Schotterpiste geht es etwas ungemütlicher, dafür landschaftlich aber umso beeindruckender nach Süden. Wir fahren auf die 2 Zwillingssiebentausender Nun und Kun zu, durch teils karge Gebirgswüste, dann wieder durch grüne und blühende Hochalmen... Im Zuge einer ca. 3-stündigen Wanderung über den Namsuru Pass erleben wir das karge Gebirge hautnah und bewundern Nun und Kun, die am Horizont das Panorama dominieren. -

Village Ralakung Geographic Location

Expedition to Electrify - Village Ralakung Geographic Location Zanskar Expedition Route Map Facts – Village Ralakung • 1200 Year Old Village nestled in the Phe block of Zanskar (Himalayas) • The most remotest & backward village of the region • Village home to 110 people and 11 Households • Village Divided into two Parts – Phema and Nagma • Village remains cut off for 7 months due to snowfall blocking passes • Accessed by helicopters for purpose of medical evacuation and voting • Known for rich minerals and natural resources • The Region is also known for Unique Volcanic Igneous rock formation • There is one primary school in the village with 8 students • Only one Satellite Phone in the village to connect with outside world • The Village doesn't have a single person who is a graduate Accessibility in Winters • Ralakung is cut off from the rest of the world for 7 months. • Can only be accessed by walking on the Frozen River for 8 days Accessibility in Winters Overall Expedition Journey- 900 KMS • 2 Days by Vehicular Journey Leh To Kargil Kargil to Phe • Total Vehicular Distance – 860 Kms (To and Fro) • 2 Days of Trekking in the Valley One side trekking distance – 45 Kms (To and Fro) • 6 Nights of Camping/Homestays in Villages • Horses carrying Solar Micro- grid material Average Altitude of Journey – 13400 ft Highest Mountain Pass During journey- 15400 Ft Trekking-40 Kms 3 days of Continuous trekking. Camping at 13000 ft. Crossing a mountain pass at 5300m Ralakung Village The remotest village of the region Of Zanskar • Hardly 40 -50 tourists have come here • Not even .01% of Ladakh has reached this village People and Houses of Ralakung 11 Households and more than 130 People Solar Micro Grid Installation Day One: You will fly into Leh from New Delhi. -

The Road to Lingshed: Manufactured Isolation and Experienced Mobility in Ladakh

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 32 Number 1 Ladakh: Contemporary Publics and Article 14 Politics No. 1 & 2 8-2013 The Road to Lingshed: Manufactured Isolation and Experienced Mobility in Ladakh Jonathan P. Demenge Institute of Development Studies, UK, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Demenge, Jonathan P.. 2013. The Road to Lingshed: Manufactured Isolation and Experienced Mobility in Ladakh. HIMALAYA 32(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/14 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Road to Lingshed: Manufactured Isolation and Experienced Mobility in Ladakh Acknowledgements 1: Nyerges, Endrew (1997), The ecology of practice: studies of food crop production in Sub-Saharan West Africa (Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach). 2: Swyngedouw, Erik (2003), 'Modernity and the Production of the Spanish Waterscape, 1890-1930', in Karl S. Zimmerer and Thomas J. Bassett (eds.), Political Ecology: An Integrative Approach to Geography and Environment-Development Studies (New York: The Guilford Press). This research article is available in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/14 JONATHAN DEMENGE INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, UK THE ROAD TO LINGSHED: MANUfacTURED ISOLATION AND EXPERIENCED MOBILITY IN LADAKH The article deals with the political ecology of road construction in Ladakh, North India. -

Mammal's Diversity of Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India

International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies 2017; 4(2): 07-12 ISSN 2347-2677 IJFBS 2017; 4(2): 07-12 Received: 02-01-2017 Mammal’s diversity of Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), Accepted: 03-02-2017 India Indu Sharma Zoological Survey of India, High Altitude Regional Centre, Indu Sharma Saproon, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India Abstract Ladakh is a part of Trans-Himalayas in the Tibetan Plateau. The area is extremely arid, rugged and mountainous. The harsh environment is dwelling to only highly adaptable fauna. During the present studies, efforts have been made to compile the diversity of the Mammals as per the present studies as well as from the pertinent literature. It represents 35 species belonging to 23 genera, 13 families and 05 orders. 11 mammalian species are endemic to the area. The conservation status as per IUCN Red list of threatened species & cites and Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1772 has been discussed. The various anthropogenic activities viz. development, construction of roads, tourism pressure, habitat degradation, hunting, poaching, illegal trade etc. are the main threats in the area. Keywords: Trans-Himalayas, Tibetan Plateau, habitat degradation 1. Introduction Ladakh-Trans-Himalayan Ecosystem is the highest altitude plateau region in India, situated in the state Jammu and Kashmir between world's mightiest mountain ranges i.e. Karakoram mountain range in the north and the main Great Himalayas in the south. State Jammu and Kashmir has 17 districts of which Leh and Kargil districts constitute the region of Ladakh. It comprises over 80% of the trans-Himalayan tract in India. It is located between 34°08′ to 77°33′N and 34°.14′ to 77°.55′ E with an area of 96,701 sq.