Lauraine Diggins Fine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 38 | 2020 Shakespeare et le monde animal Shakespeare’s Animal Anatomy of Music Katherine Cox Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/5126 DOI: 10.4000/shakespeare.5126 ISSN: 2271-6424 Publisher Société Française Shakespeare Electronic reference Katherine Cox, « Shakespeare’s Animal Anatomy of Music », Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [Online], 38 | 2020, Online since 10 January 2020, connection on 06 July 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/5126 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare.5126 This text was automatically generated on 6 July 2020. © SFS Shakespeare’s Animal Anatomy of Music 1 Shakespeare’s Animal Anatomy of Music Katherine Cox 1 Music, for Shakespeare and contemporaries, echoes the design of the universe. Revealing in its own numerical construction a parallel order in the cosmos, music is bound up in the framework of every natural thing and being. Lorenzo expresses this logic in The Merchant of Venice: “[a] man that hath no music in himself / [...] / is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils.”1 Lacking the musical sensitivity common to all people, animals, and even objects, an unmusical man is a defective and untrustworthy creature. Condemnation of the man generates questions about the animals in Lorenzo’s exemplum, the “youthful and unhandled colts” that become docile and calm when they hear sweet music (5.1.72). Are they superior to the immovable man? Or does their ability to appreciate music diminish its moral and intellectual value? Tensions such as these, lurking just below the surface in Lorenzo’s speech, arise from the appeal of music across the animal-human divide. -

Dossier Pédagogique Vénus Et Adonis |

Sommaire Préparer votre venue à l’Opéra 3 VÉNUS ET ADONIS Résumé & Synopsis 4 John Blow 5 Guide d’écoute 6 Vocabulaire 16 Références 17 VÉNUS ET ADONIS À L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Distribution 18 Entretien avec le metteur en scène 19 Costumes et scénographie 22 Repères biographiques 23 ANNEXE Fiche instruments 24 Contacts Service des relations avec les publics : OPERA DE LILLE Karine Desombre / Agathe Givry 2, rue des Bons-Enfants 03 62 72 19 13 BP 133 [email protected] 59001 Lille cedex Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration de Sébastien Bouvier, enseignant missionné à l’Opéra de Lille septembre 2012 2 Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - lire la fiche résumé et le synopsis détaillé, - faire une écoute des extraits représentatifs de l’opéra (guide d’écoute). Si vous souhaitez aller plus loin, un dvd pédagogique peut vous être envoyé sur demande. Les élèves pourront découvrir l’Opéra de Lille grâce à une visite virtuelle, les différents spectacles présentés ainsi que des extraits musicaux et vidéo. Enfin, pour guider les premières venues à l’Opéra, un document est disponible sur notre site internet : http://www.opera-lille.fr/fr/venir-a-l-opera/1ere-fois-a-l-opera/ Recommandations Le spectacle débute à l’heure précise et les portes sont fermées dès le début du spectacle, il est donc impératif d’arriver au moins 30 minutes à l’avance. -

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(S): W

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(s): W. R. Rearick Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 17, No. 33 (1996), pp. 23-67 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483551 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 17:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae. http://www.jstor.org W.R. REARICK Titian'sLater Mythologies I Worship of Venus (Madrid,Museo del Prado) in 1518-1519 when the great Assunta (Venice, Frari)was complete and in place. This Seen together, Titian's two major cycles of paintingsof mytho- was followed directlyby the Andrians (Madrid,Museo del Prado), logical subjects stand apart as one of the most significantand sem- and, after an interval, by the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, inal creations of the ItalianRenaissance. And yet, neither his earli- National Gallery) of 1522-1523.4 The sumptuous sensuality and er cycle nor the later series is without lingering problems that dynamic pictorial energy of these pictures dominated Bellini's continue to cloud their image as projected -

Bell Shakespeare Present VENUS & ADONIS by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE a Bell Shakespeare and Malthouse Melbourne Co-Production Developed Through Mind’S Eye TEACHERS’ KIT

australia’s shakespeare resource Sydney Theatre Company and Bell Shakespeare present VENUS & ADONIS BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE A Bell Shakespeare and Malthouse Melbourne co-production developed through Mind’s Eye TEACHERS’ KIT TEACHERS’ KIT: VENUS AND ADONIS CONTENTS 1 BELL SHAKESPEARE 2 ABOUT THIS KIT SYNOPSIS: VENUS AND ADONIS 3 BACKGROUND: VENUS AND ADONIS 4 THE CONTEMPORARY VISION: VENUS AND ADONIS 5 CHARACTERS: VENUS AND ADONIS 6 THEMATIC CONCERNS OF THE PRODUCTION 7 EDUCATIONAL CONTEXTS - VENUS AND ADONIS 8 PRE-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES 11 ENGLISH DRAMA MUSIC POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES 15 ENGLISH DRAMA MUSIC THE POEM: VENUS AND ADONIS 17 REFERENCES 27 © Bell Shakespeare Education 2009 1 BELL SHAKESPEARE Launched in 1990, Bell Shakespeare is a dynamic, Australian theatre company with a broad mandate to educate and entertain the public. The Company strives to present – at the highest possible standard – the works of William Shakespeare, and, from time to time, other classics. Bell Shakespeare is Australia’s only national touring Shakespeare theatre company. We are committed to taking our productions and education programmes to audiences in capital cities, regional and rural centres across Australia. We are also committed to the development and training of actors and an ongoing examination of the role of theatre in the life of the community. We believe that great theatre is a source of spiritual enrichment, wisdom and pleasure. BELL SHAKESPEARE EDUCATION ONLINE Bell Shakespeare’s education website is useful, relevant and entertaining. www.bellshakespeare.com.au/education is the key to all your Shakespearean information needs. About This Kit This kit has been devised for use in Senior English, Drama and Music with preparatory and follow- up exercises for students. -

Venus and Adonis

0043 CD Booklet RPM.qxd 06-12-2010 09:43 Page 1 ohn low JVenus andB Adonis Theatre of the Ayre Elizabethdirected by Kenny 0043 CD Booklet RPM.qxd 06-12-2010 09:43 Page 2 Theatre of the Ayre Elizabeth Kenny JOHN BLOW 01 Cloe found Amintas lying (A Song for Three Voices) 06.20 02 Ground in G minor for violin and continuo 03.56 MICHEL LAMBERT 03 Vos mépris chaque jour me causent mille alarmes 03.41 ROBERT DE VISÉE 04 Chaconne 05.12 JOHN BLOW Venus anD ADonis 05 OVERTURE 03.37 PROLOGUE 06 Cupid ‘Behold my arrows and my bow’ 07.00 07 Cupid’s Entry 01.14 08 Tune for Flutes 02.33 ACT 1 09 Adonis ‘Venus!’ 02.27 10 Hunters’ Music 03.51 11 Chorus ‘Come follow, follow to the noblest game’ 02.32 12 A Dance by a Huntsman 01.19 13 Act Tune 01.54 ACT 2 14 Cupid ‘You place with such delightful care’ 01.56 15 The Cupids’ Lesson 03.03 2 0043 CD Booklet RPM.qxd 06-12-2010 09:43 Page 3 Cupid and the little Cupids ‘The insolent, the arrogant’ 16 A Dance of the Cupids 01.28 17 Venus ‘Call the Graces’ 01.08 18 Chorus of the Graces ‘Mortals below, Cupids above’ 01.22 19 The Graces’ Dance 01.26 20 Gavatt 00.46 21 Saraband for the Graces 01.22 22 A Ground 01.52 23 Act Tune 02.39 ACT 3 24 Venus ‘Adonis!’ 05.03 25 Venus ‘With solemn pomp let mourning Cupids bear’ 07.05 Theatre of the Ayre Elizabeth Kenny director/theorbo/guitar Venus Sophie Daneman Adonis Roderick Williams Cupid Elin Manahan Thomas Soprano and shepherdess Helen Neeves Alto and shepherd Caroline Sartin Tenor and huntsman Jason Darnell Bass and shepherd Frederick Long Cupids from Salisbury Cathedral -

Venus and Adonis

VEN US AN D A D O N IS WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ED ITED , WITH NoTE s , I NTRODUCTI ON A Y D G LO S S R , LI ST O F VA RI O RUM REA A T T B Y ING S , ND S E L EC ED CRI I CI SM, CHARLOTT E PORTER NEW YORK W THO MAS Y. C RO ELL CO MPANY PUBLISHERS “ H L. 26 1 91 2 J/ Co pyright I 0 , 9 3 , by T O AS Y. H M CROWELL 8: CO . Co ri ht py g , m m , by THO AS M Y . CROW ELL CO PA M NY. CO N T EN T S INT RO DUCT IO N Ex PL ANAT ORY BIOG RAPHY VENUS AND ADO NIS NOT ES I A RG UMENT II SOU RCES III DU RATIO N O P T HE ACTIO N Iv DATE O P CO MPOSITIO N v EARLY EDITI ONS VI LIT ERA RY ILLUST RATIONS E! PLANATO RY : ABBREVIATIONS OP EDITIONS C O NSU LTED A G LOSSARY OP WORDS : G RAMM ATIC AL USAG E AND PRONUNCIAT ION A LIST OE V ARIORUM READINGS SELECT ED C RITICISM INTRODUCTION enus ids h er senses fear the fantasie no more V b , and with th at word sees th e hunted boar e wh ose red bepainted frothi e mouth is like mingled milke ’ and ood it is ess a dream come true th an a dreaded bl , l second dream such as ever one h as fe t s readin , y l , p g ’ r u h all th e sin n f th o g ews a seco d eare. -

1 1. Alessandro Scarlatti Was an Italian Baroque Composer Who Lived

1. Alessandro Scarlatti was an Italian Baroque composer who lived from 1600-1725. Father to Domenico and Pietro Filippo Scarlatti, Alessandro is also father to the development of an opera style bridging the Baroque and Classical periods, as well as an innovative composer of chamber cantatas. Scarlatti’s early works, primarily operas and secular cantatas, were written and performed in Rome until 1684. These operas, or “opera seria”, were relatively short and included much comic relief injected into the often heavy or tragic plots. In 1677, the Pope outlawed public opera. Thus, Scarlatti’s early operas were performed only privately in palaces of the Roman aristocracy and clergy. In 1684, Scarlatti became director of the Chapel Royal to the Viceroy of Naples, a prestigious post that allowed him to create large-scale operas with involved, elaborate plots and ornate scenery. Most importantly, these new operas featured a pioneering development of Scarlatti’s: the da capo aria, occurring at the climactic, most stirring part of a scene. This added to the emotive intensity of the plot, keeping the audience more engaged as well as more clearly delineating the narrative of the story through keeping scene transitions more obviously marked. After leaving Naples in 1702, Scarlatti returned to Rome where he developed the grand da capo aria and the Italian overture in three movements (fast-slow- fast) in his 1705 serenata for soprano and castrato soloists with orchestra, Endimione e Cinta. Scarlatti returned to Naples and later to Rome between 1708 and his death in 1725, recommencing his Chapel Royal position. By this time, aria-centered opera is at its peak of popularity and bel canto singing now “assumes its 18th century definition as vocal music which features elaborate coloratura embellishment which rivals instrumental technique.”1 His formal 3-act opera buffa (comic opera), Il trionfo dell’onore, is the first of its kind, premiering in Naples in 1718. -

Chapter 8: Music Travels: Trends in Italy, Germany, France, and England

Chapter 8: Music Travels: Trends in Italy, Germany, France, and England I. Introduction A. During the seventeenth century, instrumental music rose in prominence and respect. B. Different political climates in Italy, France, Germany, and England resulted in national musical styles. II. Instrumental Music A. Some Organists: Frescobaldi, Sweelinck, and Others 1. Formal plans that did not depend on a text allowed instrumental music to expand to substantial compositions. 2. Written examples demonstrated what a virtuoso performer could do in improvisation. a. The music of the organist at St. Peter’s, Rome, Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583– 1643) is a good example of how this works. 1) He was a flamboyant composer whose music illustrates that early seventeenth-century musicians performed in an almost excessively impressive style. 2) Twelve of his sixteen published volumes are of instrumental music. 3) Two genres associated with him are the toccata and partite. a) Toccatas turn the act of playing into a form of theater, thereby linking them to current trends in vocal music. b) Frescobaldi’s toccatas are sectional and can be ended where need be. 4) His partite, or variations, were inventive works that evince years of improvisation. a) They include examples of the passacaglia and ciaccona. b. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621), a Dutch organist, was another famous composer, chiefly known for improvisation. 1) He published old-fashioned vocal music but also performed in a modern style on the keyboard. 2) English Catholic composers who moved to the Netherlands introduced Sweelinck to the music of the virginalists (English keyboard composers), including Byrd. B. Lutheran Adaptations: The Chorale Partita and Chorale Concerto 1. -

Venus and Adonis C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century Titian and Workshop Titian Venetian, 1488/1490 - 1576 Italian 16th Century Venus and Adonis c. 1540s/c. 1560-1565 oil on canvas overall: 106.8 x 136 cm (42 1/16 x 53 9/16 in.) framed: 134.9 x 163.8 x 7 cm (53 1/8 x 64 1/2 x 2 3/4 in.) Widener Collection 1942.9.84 ENTRY Even more than in the case of the Venus with a Mirror, the Venus and Adonis was one of the most successful inventions of Titian’s later career. At least 30 versions are known to have been executed by the painter and his workshop, as well as independently by assistants and copyists within the painter’s lifetime and immediately afterward. The evolution of the composition was apparently highly complex, and scholars remain divided in their interpretation of the visual, technical, and documentary evidence. While there is general agreement that the Gallery’s version is a late work, dating from the 1560s, there is much less consensus regarding its quality and its relation to the most important of the other versions. The subject is based on the account in Ovid, Metamorphoses (10.532–539, 705–709), of the love of the goddess Venus for the beautiful young huntsman Adonis, and of how he was tragically killed by a wild boar. [1] But Ovid did not describe the last parting of the lovers, and Titian introduced a powerful element of dramatic tension into the story by imagining a moment in which Venus, as if filled Venus and Adonis 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Sixteenth Century with foreboding about Adonis’s fate, desperately clings to her lover, while he, impatient for the hunt and with his hounds straining at the leash, pulls himself free of her embrace. -

Full Contents and Other Works by Blow…(PDF)

STAINER & BELL INFORMATION SHEET ASK 49 (1) BLOW, John Library Volumes: Anthems I: Coronation and other Anthems edited Anthony Lewis and H Watkins Shaw. Stock No. MB7 Anthems II: Anthems with Orchestra edited Bruce Wood. Stock No. MB50 Anthems III: Anthems with Strings edited Bruce Wood. Stock No. MB64 Anthems IV: Anthems with Instruments edited Bruce Wood. Stock No. MB79 Complete Harpsichord Music edited Robert Klakowich. Stock No. MB73 Complete Organ Music edited Barry Cooper. Stock No. MB69 Venus and Adonis edited Bruce Wood. Stock No. PC2 § § Performing material corresponding with PC2 is available for rental or for purchase: Venus and Adonis edited by Bruce Wood. Version 1 (Original). Score and Parts. Catalogue no. HL391A. Rental Venus and Adonis edited by Bruce Wood. Version 2 (Revised). Score and Parts. Catalogue no. HL391B. Rental Venus and Adonis edited by Bruce Wood. Version 1 (Original). Performance Score. Stock No. Y281 Venus and Adonis edited by Bruce Wood. Version 1 (Original). Set of Instrumental Parts. Stock No. Y282 Venus and Adonis edited by Bruce Wood. Version 2 (Revised). Performance Score. Stock No. Y283 Venus and Adonis edited by Bruce Wood. Version 2 (Revised). Set of Instrumental Parts. Stock No. Y284 Works by John Blow are also contained in: Anthology of English Music for the Harp (edited David Watkins). Stock No. H140 English Keyboard Music 1650-1695: Perspectives on Purcell (edited Andrew Woolley). Stock No. PC6 Junior Recitalist, The, Book 1. Stock No. D81 Junior Recitalist, The, Book 2. Stock No. D83 John Blow’s Anthology (edited Thurston Dart). Stock No. K37 Musick’s Handmaid, Second Part (edited Thurston Dart). -

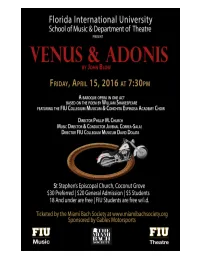

Venus and Adonis SSCM Program

Welcome! It is with great pleasure that we present today’s performance of John Blow’s Venus and Adonis. Inspired by William Shakespeare great narrative poem by the same name, it represents one of the earliest known examples of English language “opera,” notwithstanding its true calling as a masque for the court of Charles II. At FIU, we strive to give our young singers the opportunity to perform a wide variety of rep- ertoire from across the centuries. Our choice of this opera was inspired by the exhibit of Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623) at the Patricia and Philip Frost Art Museum on FIU’s main campus, and we’re de- lighted to be part of the celebration! We are particularly thrilled to welcome the members of the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music to Miami. We thank you for your support and hope you enjoy our presentation of this exquisite rarity from the English Baroque. - Robert B. Dundas, Director of the FIU School of Music Message From the Director “No man is an island.” So said John Donne. In this respect it might well be that each of us is an essential mirror for the other, our lives validated through our reflection in the eyes of others. In John Blow’s opera, Venus and Adonis (1684), the theme of love is laid out before us with a cast of characters who proceed to trivialize it as an expendable commodity to be toyed and played with. Everyone is feverishly caught up with the idea of love as a concept. Venus and Adonis was originally staged as an entertaining “masque” for King Charles II and applauded by an elite audience of courtiers and aristocrats, irresistibly drawn to the comedy of self-reflected idola- try.